“It’s not wholly unlike seeing people talk about Faerie”. [1] ‘Do you ever see wild animals?’ is a question trapped in the net of binaries. This blog takes as its case study Amal El-Mohtar (2025) ‘The River Has Roots’, London, Arcadia, Quercus Books.

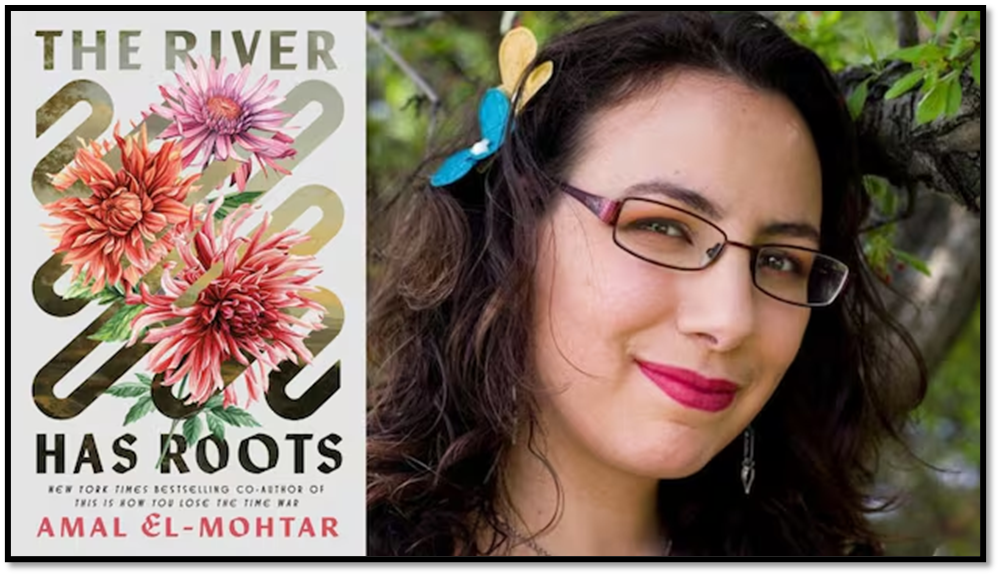

‘Wild animals’ possibly don’t exist except as the ‘other’ to two norms the thing we think of as ‘self’ : the ‘human beings’ (or more strictly to move out of the binary straight away – human animals) against which ‘animals’ are defined and the ‘tame’ against which the ‘wild’ is defined. This question starts with an unspoken subject – the socialised and civilised human examining its stored concepts of its opposites – the ‘wild’ and the ‘animal’, looking for instances where wildness and feral nature exist outside of boundaries set for them by that which considers itself their master. The trick is in the last phrase – we have to look for a space where the wild and the animal are allowed to be outside our ken, and at the same time suppose those spaces are under our physical, cognitive and emotional control. We define them out of existence in order to taunt our controlling ability to imagine them in acceptable form – a ‘wild animal’ that is not seen as a threat and against which our defences of superiority are built, and hence neither true to what might be imagined as freely ‘wild’ nor ‘animal’.

In the book I am looking at today, wild fauna and flora cannot exist because they are products of the Modal Lands for those ‘were particularly thick with strange wildlife’. It is strange for it cannot be entirely wild, but is instinct with the human language that interprets it, so that it consists of ‘small grey rabbits with uncommonly human eyes’, ‘clumps of nettles waving in the wind’ that spell out your name, birds ‘singing with a dolourously human voice’ that make ‘a deep ache in your breast …., the pain of which no one, …, could translate away’. [2]

However, there is another aspect of the book’s interest in the concept of the lands people or peoples think they ‘own’ as theirs by some contracted right. There is, in the beautiful acknowledgements pages a beautiful thank you to those who have refused to see the facts of genocidal attack in Palestine, against the supposition that it is not definable as ‘genocide’ nor happening in a definable nation owned by a specific people. It is here where El-Mohtar says that these naysayers, those complicit with massive violence on a truly appalling scale, talk of Palestine as something that does not exist: “It’s not wholly unlike seeing people talk about Faerie”. [1] Palestine, like Arcadia (the country of Faerie) is, that is, thought to be something whose authenticity is doubted because it is not in the realm of the ideas of the norms we are able to defend as within our reach of accepting. If it has existence, it is other than those things that relate to undisturbed notions of the self as a fair and just human entity. Fairness and justice then are, therefore, not concepts applied to Palestine by too many.

This moment in the acknowledgements is difficult to relate to the story proper, except that the land of Faerie, known as Arcadia, is also seen as a place that cannot be domesticated, owned or settled nor seen as relatable to a boundaried idea of the human being, with its binary markers of male and female, real and imagined, civilised or wild. Where the possible allegory parts from Palestine, Arcadia’s inhabitants are shape-shifters and hence also non-binary, and the lover of the protagonist Esther, Rin, is throughout known as ‘they’ and Rin is a non-binary name in Japanese.The name however can also be transliterated as Lin, making Rin to fade into the Scottish ballad Tam Lin, so often cited in the book, which has to do with Faerie lovers.

Undefined by any unitary category, each is no more and no less than its potential desired transformations. Its governance is imagined then as that of grammar, but a grammar of a language that refuses to be tamed by the structures of those the ‘civilised’ world calls ‘grammarians’ in their universities. A grammarian in Faerie, or even one capable of living on its borders, in the Modal lands, and visiting, like Agnes Crow. Agnes is a Faerie grammarian; that is, a student of free transformation (though she needs the Faerie magic of Rin to complete more difficult translations, called a ‘witch’ by those who demand categories to structure the world and make it livable to them. (I suspect if I knew Chomsky better as a linguist my head would be buzzing even more now, but I don’t).

Amal El-Mohtar (2025: 1) ‘The River Has Roots’, London, Arcadia, Quercus Books.

When grammar was wild, when, that is, it lived in a world of fantasy not of regulation, it welded together the binary of new and the old into multiple possible forms of invention, not all of it human, little of it reasonable. The Modal lands on its borders, if it can be said to have borders (a riddle propounded in the story is ‘what is a country without borders’, a country say like ‘Palestine’ and ‘Faerie’ countries at the level of desire, hence Arcadia and the desire it articulates that a thing be true) is that country which lives in the Modal in grammar.

The action of grammar in this story is most often conjugation, the name of the process by which differences of voice, mood, tense, number, and person are identified in the changing appearance of a verb in speech or writing. Conjunction is a means of joining a root, or source, of the verb with its different branches or forms and underlines the two basic metaphors of the novel: the onward and fluid across vertical and lateral space or upward and static in one place respectively motion and transformation of rivers or of trees, whose roots are held static unlike those of rivers.This is all allegorised, if that is the words in the willow trees called the Professors who bridge the river Liss and tame its motion, forming a place after which the River Liss, which flows from and through Arcadia, after which the ‘the landscape stills and settles’. The trees are named after the human contract by which humans define themselves against animals and the supernatural both, as capable of joining to each by force of a speech act.

Amal El-Mohtar (2025: Facing page 1) ‘The River Has Roots’, London, Arcadia, Quercus Books.

These trees are Professors because they ‘once’ were, are, and will be lovers who, having professed love to each forever, must seem to choose to stay in place – growing up but never growing around and beyond fixed boundaries of hard bark, their skins. As grammarians, they also prefigure the Professors of linguistics, who ‘clump together like clauses at the universities of the east and north’- that’s how the allegory works, by slippery conjugation with other domains, which joining together sometimes hardens and then loosens to something more fluid. The willow Professors are also ‘great grammarians’ but not ever as dry as their University common name bearers. Nevertheless, they tame ‘wildness’ in Faerie water and use it for the interests of their own, and no thing else’s ‘growth’:

Their roots are uncommon thirsty; like tightly-woven nets they sift grams after gram of bucking wildness from the water and pull it into their bodies. The river may conjugate everything it touches, but the willows translate its grammar into their own growth, and hold it slow and steady in their bark. [3]

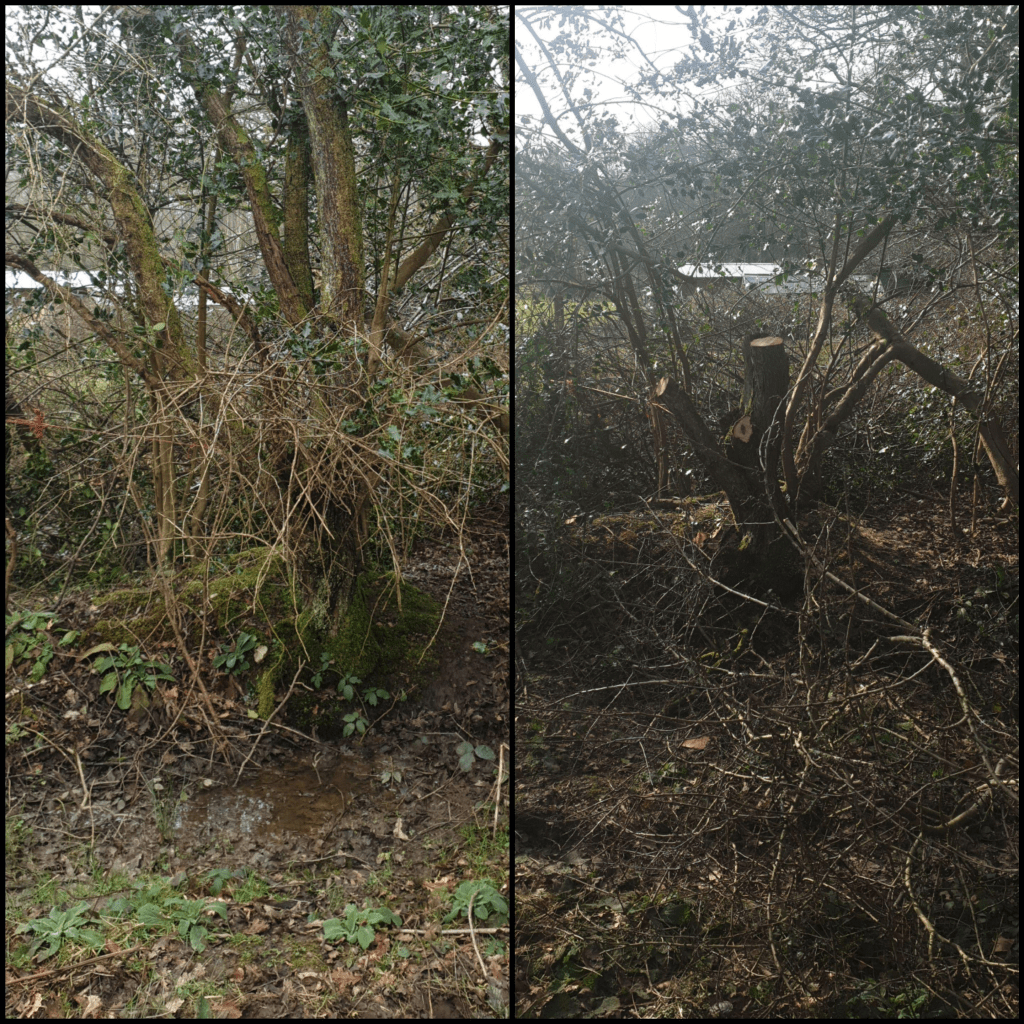

The willows have human qualities that are not necessarily positive – bounded by their own skins, they thirstily exploit what they get for their own interest, as do the other tree types which are the names of human families – even the protagonist Hawthorns who have enough land for their nearest neighbour Samuel Pollard to covet its conjugation with his own by marriage with Isabel, displacing Rin in the process. Samuel thinks the union of Hawthorn and Pollard land make make the Hawthorns themselves ‘closer to the wholesome, settled tameness of Thistleford’, the latter being their common town of residence. Pollard is a name that defines the active force of regulation, supposed necessary, for trees, particularly unruly hawthorn, where a tree is radically pruned.

Samuel Pollard is an extreme of regulated hatred in this novel – the type of the murderous lover moreover, like Browning’s Porphyria’s Lover. Isabel however loves murder-ballads. But his name also conveys an attitude to pollarding trees, especially old ones. Esther finds the university educated Samuel repulsive in look (with eyes so tame that they had ‘the soft, beseeching expression of a whining dog’, his manner of touching her skin with ‘cold and moist’ hands’ and his pretentious and mannered behaviour. [4]

Hawthorn tree before and after pollarding, by spandit, at: https://arbtalk.co.uk/forums/topic/136446-hawthorn-coppice-pollard-or-ignore/

There is much more to say of both trees and rivers – but it would be better to read the wonderful story, so let’s return to ‘strange wildlife’ again and the wild swan which plays such an important part in the story’s transformations, being the thing the murdered Esther transforms into after the combined effects of her drowning in the Liss: ‘the water stealing her breath, the hands pushing her down, the grammar unraveling the order of her body’.[5] Agnes Crow (lots of birds are important in the story too) recognises the netted swan she sees in it not a wild thing caught but a dead thing alive, ‘Rin’s betrothed decoupled’n as ‘something marred’. Marring, by the way is an important word, where transformations go awry:

Marred is what people called the unwelcome actions of grammar, and like paper torn by the press of a pencil, there was no way to set them right. [6]

But the description of this swan experiencing the necessity of being caught and trapped, in order to be saved and truly freed (more compromised binaries), contains as near as this story gets to the essence of a literary ‘capture’ of the ‘wild animal’, for that bird is already necessarily webbed in linguistics; the semantics of a vocabulary and the transformation done by grammar:

A swan’s language is a swirl of currents, in water and air: a swan’s body reads a kind of literature in the waves and clouds before launching herself between their lines. But this swan’s understanding of herself and her situation was troubled, and she was frightened and angry. Why was this obstruction in her path? Why could she not paddle against the water pushing her towards this strange object? Why did she want to lift her voice and scream when there was nobody near by to speak to, and where were her people.Why were there so many, many colours?

She lifted the long grace of her neck and flapped her wings to beat against tjhe water. There was something on her body, some thing somehow constricting and comforting, and she could not bear the contradiction – that she was trapped, and this was good, but she was also free, and this was terrible. She could not bring herself to fly.[7]

This is remarkable even down to the sex-gendering of the body of the swan; both because it remembers being Esther’s body, and because it can only see its kind capture by Agnes as a repeat of the vicious one of Samuel Pollard that brought about her marred grammar. And she cannot be merely wild – never an it or they – but some subject aiming to understand its wildness in the context of being tamed – by human language, as well as human views of what it is to feel contradiction rather than panic. To be free can be good as well as terrible, and vice-versa with being trapped. For the best things in lives humans imagine, if not swans, through their language that seem to free our spirit also trap – like marriage, perhaps even being in love with anyone but a shape-shifter. and don’t the nets of language trap us, even though they can also, at the same time, give us the keys to freedom (both good and terrible too at the same time. We never get the ‘wild swan’! Being aware of this offers a way even to reading Yeats’ The Wild Swans at Coole, for the perceiving man’s decline into the prison of his body somehow catches the swans in their attempt to be free, never lifting off as they did in the lyric voice’s memory.

This is not a review of El-Mohtar’s story, for, in such a short novella, it is packed with more than can be said in the dull language of a commentator rather than a creative story-teller. You will, of course, love it – be bound and freed by it. However, when you find you love it, be prepared to be blown away by the fantasy short story bound in with the English edition, John Hollowback and the Witch, for it is a story so full of social understanding of sex/gender but still a fble that you will marvel at it. But, as you finish the book, remember to read the Acknowledgements and fulfil the author’s ‘hope’ that ‘you’ll read it all the way to the end’. The end will, of course, recede from you, for it ends with the puzzle that puts the fate of Lebanon, and the whole of Palestine, into focus, calling for the realisation of ‘a shared urgency in confronting that horror’.[8] Share with your perceptions, if you will. We need to begin to use language to set ourselves free – the language of a ‘Free Palestine’ that seems to too many be life Faerie, ‘and everyone knew it, even if no one spoke in words so plain’:

No one looks directly at the sun, for all it illuminates the world, and Faerie being the source of so much grammar made folk apt to speak of it in a kind of translation. They called it Arcadia, the Beautiful Country, theLand Beyond, Antiquity. And if they sometimes meant things less pretty than those names suggested, well, there are always things lost in translation, and curious things gained.[9}

I love that and it makes me shudder too. Do read this BEAUTIFUL TRAGIC book. You will notice the beauty – the tragedy is like that that lies beneath the murder-ballads it vaunts, and the beauty and tragedy of folk song and balladry.

Bye for now

With love, Steven xxxx

PS. And, of course, I have never seen a ‘wild animal’ for we have imprisoned them all in human problems.

___________________________________________

[1] Amal El-Mohtar (2025: 133) ‘The River Has Roots’, London, Arcadia, Quercus Books.

[2] ibid: 6

[3] ibid: 2

[4] ibid: 16

[5] ibid: 52

[6] ibid: 7

[7] ibid: 70f.

[8] ibid: 130

[9] ibid: 5