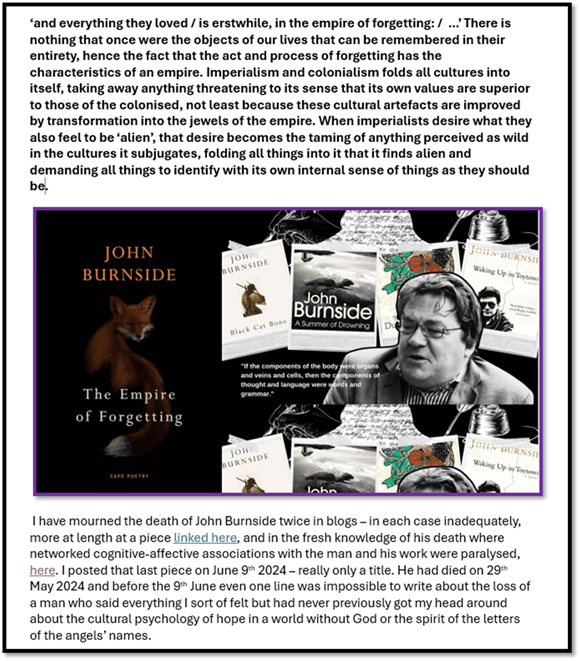

To the memory of John Burnside and in dear friendship for Joanne, I contemplate. the poet’s posthumous lines: ‘and everything they loved / is erstwhile, in the empire of forgetting: / …’ [*] There is nothing that once were the objects of our lives that can be remembered in their entirety, hence the fact that the act and process of forgetting has the characteristics of an empire. Imperialism and colonialism folds all cultures into itself, taking away anything threatening to its sense that its own values are superior to those of the colonised, not least because these cultural artefacts are improved by transformation into the shining but meaningless jewels of the empire’s possession. When imperialists desire what they also feel to be ‘alien’, that desire becomes the taming of anything perceived as wild in the cultures it subjugates, folding all things into it that it finds alien and demanding all things to identify with its own internal sense of things as they should be. All we have left to redeem us, dearest Joanne, is the hope that lies in magical thinking .

I have mourned the death of John Burnside twice in blogs – in each case inadequately, more at length at a piece linked here, and in the fresh knowledge of his death where networked cognitive-affective associations with the man and his work were paralysed, here. I posted that last piece on June 9th 2024 – really only a title. He had died on 29th May 2024 and before the 9th June even one line was impossible to write about the loss of a man who said everything I sort of felt but had never previously got my head around about the cultural psychology of hope in a world without God or the spirit of the letters of the angels’ names. I have only just got around to read his posthumous (incomplete) volume of poems.

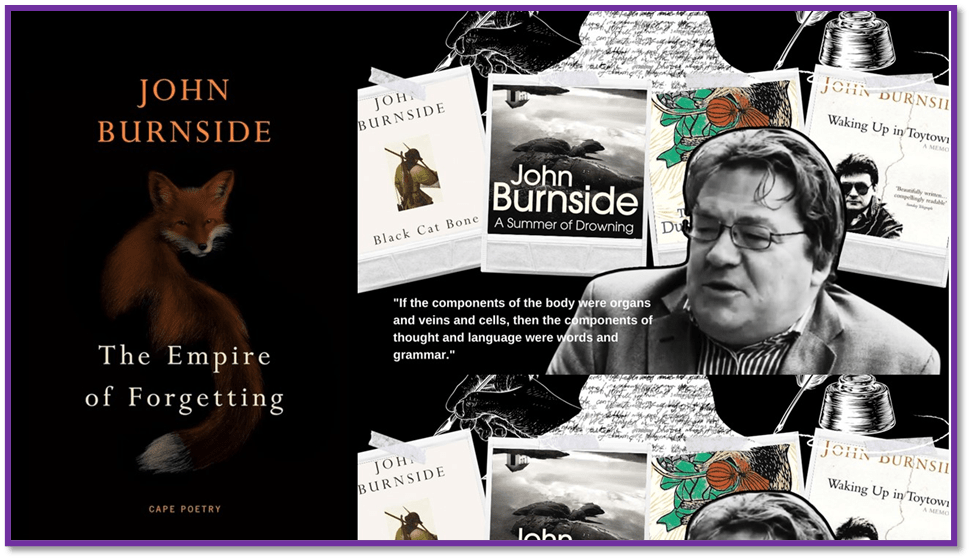

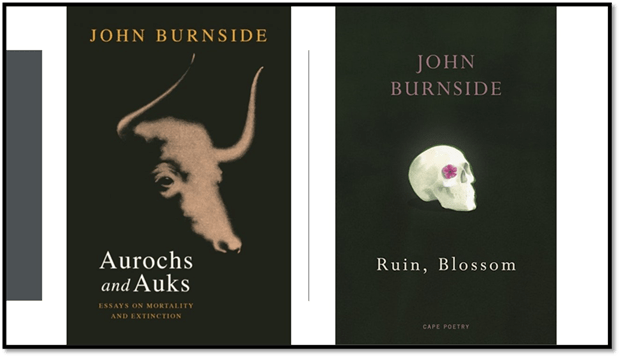

I have long been a follower of the work of Burnside, and have expressed my love of that great storyteller, memoirist, spiritual thinker and poet already several times, though much of that writing is lost – the blog on the last volume of poetry Ruin, Blossom in his lifetime for instance does persist (see it at this link), as does my poor blog on Ashland and Vine – a fine novel but not his greatest (here at this link) and the late great essays in Aurochs and Auks: Essays on Mortality and Extinction (here). You need to read Ruin, Blossom and Aurochs and Auks to get the savour of why these posthumous poems about the essence of the mortality, not only of flesh and in neurobiology and neurochemistry, but of the metamorphoses of memory (both its losses and memory transformations that flesh and neurobiology and neurochemistry enable). I hope my blogs on those two works help make that step for you.

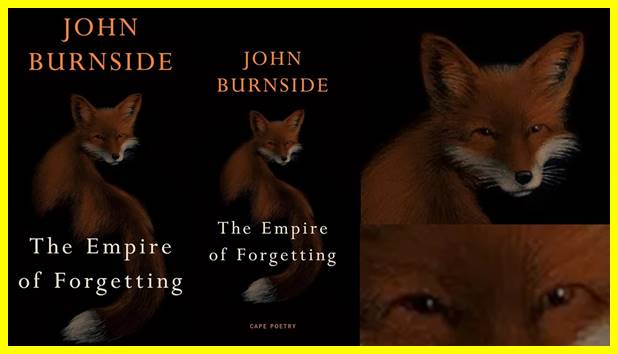

However, launching into ponderous thoughts about Paul Ricoeur, the phenomenological philosopher Burnside cites as his source for the French concept of ‘l’empire de l’oubli’, a term which can also be found in other French thinkers with interpretive differences of usage, isn’t going to happen here, for somehow I feel the poetry is so independent of such analogues for its emergent concepts – for the analogues that contribute a part to its whole are too many. Instead I look at the cover of the book with a fox that seems to stare into the reader’s eyes. And in responding to this volume I have been haunted by my pain at a dear friend’s words: I use only her first name Joanne. Joanne has recently told me that my insistent belief in ‘magical thinking’ as a remnant of child development, as in Piaget and Freud, was a contradiction of her own way of thinking and surviving a world whose rationalism is the means of preserving a cruel status quo, and of the truth of spiritual prediction of change in existent worlds. Hence her thoughts will resonate through this, though only she may recognise this.

Cape’s poetry editor – Robin Robertson – says that though Burnside before his death and in preparation for this volume’s completion – which never happened – sent him ‘some familiar images by Magritte and De Chirico’ (everyday surrealist stuff we might imagine) he added whether “we felt we could prevail on Tim again, …”; Tim Robertson was the cover illustrator/designer for both Aurochs and Auks and Ruin, Blossom.[1] Tim had a fascination with how images of mortality and extinction look but how they gaze back at the looker in recognition:

We cannot know whether Tim Robertson’s eventual choice of cover illustration would have been that of the poet himself but we can have an informed view of why Tim believed Burnside would favour it, as a reflection of the poems, if one that sought its inspiration from the books marginalia of curious reading in stimulation of the poems. Here is our lovely fox and her eyes (I say her for a reason):

The illustration must, I believe, relate to the lyric ‘As If From The End Times: (Homage to David Garnett)’. Garnett surely is a denizen of the ‘Empire of Forgetting’, a place where we imagine that ‘all the books are gone’ and there will be ‘nothing to remember’ but that we remember some scene at a distance from us, perhaps at the ‘far end of the road’:

Where something live is moving in the snow.

A woman or a fox, it’s hard to say.

Now snow and the prints of foxes who have crossed its virgin fall are frequent things in Burnside. I remember asking about them in his wonderful novel The Devil’s Footprints, when I saw in Edinburgh on the year of its publication, 2007. Associated with folktales stories the animal or other origin of prints in new snow are, I think what remains of the concept of supernature and the spiritual, and this poem is about such reflections on the approach of the ‘end times’, a richly felt moment where mortality, extinction (of species) or single lives might have already found its way into our comprehension of what heretofore we found incomprehensible:

- you never know for sure, although you know that something here is coming to an end: last day of weather. Lanternlight crossing the yards, last of those stories our kinsfolk used to tell of woman into fox, fox into deer, deer into shadow and, always, the darkness-to-come.[2]

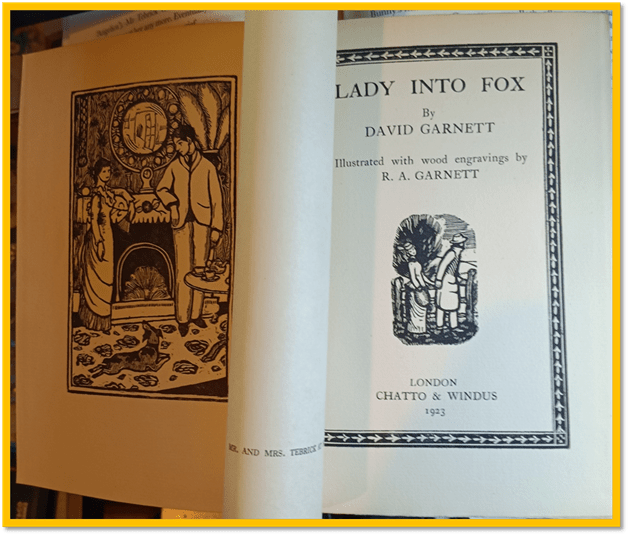

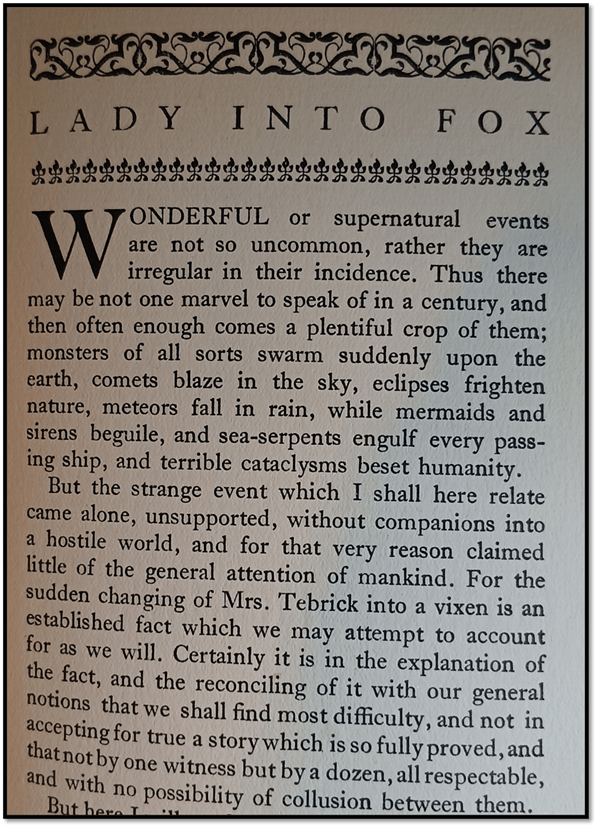

That ‘woman or a fox’ or folktale-like stories of animal metamorphoses are placed in some ancient time of rural hard work and evening stories but the homage to David Garnett suggests that such atmospheric retrospect is not unlike his in another ‘forgotten book’(since books do get forgotten even under the regulation of national library archives and have done since the great library of Ashurbanipal, David Garnett’s Lady Into Fox, published first in 1922, dedicated to David ‘Bunny’ (the name by which the Bloomsbury Group knew him) Garnett’s long-term lover, Duncan Grant, and illustrated by Garnett’s then wife R.A. (known as ‘Ray’) Garnett – it was these illustrations, Sarah Knight, Bunny’s biographer, claims, was the reason Chatto & Windus were willing to publish the book at all.[3] The book has a reference in it to a favoured foxy-young-child-fox, Angelica who charms her human father-in-law, the same name as the daughter of Virginia Bell to Duncan Grant, whom Bunny pronounced at her birth he would marry – and did, with his ex-male-lover’s blessing as her father. Indeed David started his affair with Angelica Bell whilst still officially tied to Ray Garnett. Sarah Knight also says that Bunny – bunnies get eaten, fur included, in the story by the lady who turns into a fox – ‘only after the book was published’, then ‘realised it was a metaphor for what he believed to be the absurdity of fidelity in marriage’.[4]

The title page of my copy (a 1923 sixth impression – this book was immensely popular by the standards of its time)

But Knight here really shows the most reductive of readings of the artist that Garnett was, pretty common in publishing about the marginal characters of the Bloomsbury Group at that period, and to whom Burnside paid homage, for Burnside believed in writing and its connection to deep truths. For him Garnett need to be taken seriously in his opening paragraph, which is written in the queerest of tones – in one sense totally given up to the truth of magical thinking and the transformations it involves, and sometimes foretells but always bases in the domain of the mythic past. Of course there is a jolt in turning from the almost Shakespearean ‘eclipses frighten nature’ (couldn’t Gloucester have said that in the first scene of King Lear) or some almost a kind of nonsense poetically described that seems more real in aping a contradiction whilst not stating anything necessarily contradictory (for rain does not deter meteor showers: ‘meteors fall in rain’. The idea of ‘the sudden changing of Mrs Tebrick into a vixen’ seems too absurd either to be of the scale of a ‘swarm’ of mermaids, sirens and sea-serpents appearing ‘before every passing ship’.

It is even more problematic to call that transformation an ‘established fact’ in the light of legendary events that do not even vie for the qualification of truth as statements. Burnside puts the metamorphosis of ‘women into fox’ into the context of fireside folktales (itself a rather archaic idea in the late twentieth-century and onwards) as an element of the contradiction posed into life by the inevitability of ;the darkness-to-come’, where ‘dark’ takes on the obscurity of the shadow the deer turned into in the previous tale summary and relishes its ambivalence, as the true source of super-nature and wonder – that which is ‘irregular in incidence’ but happens. Should I say that Burnside reads Garnett as carrying forward the notion of witness to the event that the normative world calls queer. And the queerest thing of all is that it is a-normative to confront is the notion of endings and of mass death – such that we deny not only the massive increase in the extinction of species but the possibility that we are constructing our own environmental Armageddon, not unlike the unknown of the personal death Burnside knew he was facing soon.

In my bleakest imaginations about the world, I have been heavily influenced by Burnside, but there is a sense that he speaks through a tradition that I hesitate to call ‘literary’ but which speaks of the world as a thing we have to grasp the apprehension of imaginatively, and Burnside’s use of past literatures – books going out of public knowledge indeed – is near to that of the Romantics since Goethe and Schiller, who have emphasised that myth speaks not only to our imaginations but imagines the truest realities of what the world is becoming. I once thought around this issue where I used A.S. Byatt’s Ragnarok as my text:

What I sincerely want is for me, and the consciousness of groups, to be truly in-formed by issues of ecological ‘apocalypse’ and the imagination of their significance in global terms – including their significance to the poorest parts of the globe, who will be eco-destruction’s first casualties and victims. And this perhaps needs us to respect myths as much as facts. At the end of Ragnarok: The End of the Gods, Byatt says, brilliantly and with as much passion as at her very finest:

Myths are often unsatisfactory, even tormenting. They puzzle and haunt the mind that encounters them, They shape different parts of the world inside our heads, and they shape them not as pleasures, but as encounters with the inapprehensible.

A.S. Byatt (2011: 161) ‘Ragnarok: The End of the Gods’ Edinburgh, London.

It is at this level – an encounter with the otherwise inapprehensible – that we need to be more informed about the certainties of global ecological disaster implied in what we know already, even now in direct experience and observation as well as scientific prediction, if the human race is not to end in brutal top-down governance of resources for the benefit of the Few not the Many. In the little space those dinosaurs I call the Few survive, in their ignorance and selfishness, they too will find it all ends for those self-assumed ‘Gods’ they think they are as well. [5]

However infantile people believe my politics to be, I stick by that. Byatt’s book is one of the best fables of global endings, but they are always implicit in Burnside’s work, whenever he is talking of endings and he was, I believe, aware of his own oncoming death for a long time – though that cannot explain that all of his works enact the apocalyptic – the things gone, or about to be, that fail otherwise to be imagined, even the existence of books and reading; poetry in particular. His equal concern with religious/spiritual/natural (like blossom from a ruin) redemption myths are, therefore, all the more important when they happen. Burnside’s belief that we get art that reminds us of this throughout history, as it contemplates the prediction of ruin-to-come in the ruins of the past in which it might find its own fate replicated.

I think Burnside’s evocation of Lady into Fox is an evocation of magical thinking as the stuff of story, myth if you like, that hovers over what rationalism cannot explain, which, of course, must include that considered ‘abnormal’ and which the patch cover-name of psychosis cannot actually comprehend, an idea explored in the first volume, A Lie About My Father, of Burnside’s two book memoir, and all of his beautiful novels and poetry. For, in a world where religion holds neither authority nor validity, our only model of supernatural being, spirit, lies in the child’s journey through magical thinking and its loss to the dry ego and its servant, reason. Now, when I have dwelt on this before I now know my friend Joanne as seen this as in contradiction to a belief in a world of belief beyond mere mental reason. Yet I don’t think it does invalidate such worlds, because, with Burnside and Byatt, I believe, the world of remembered story – whether oral myth, the origin epics of ancient cultures, or even the stories remembered from childhood where super-nature must rule in folk, fairy or demonic forms – is our only access to models of dealing with that beyond reason – which the idea of extinction or redemption must be an example.

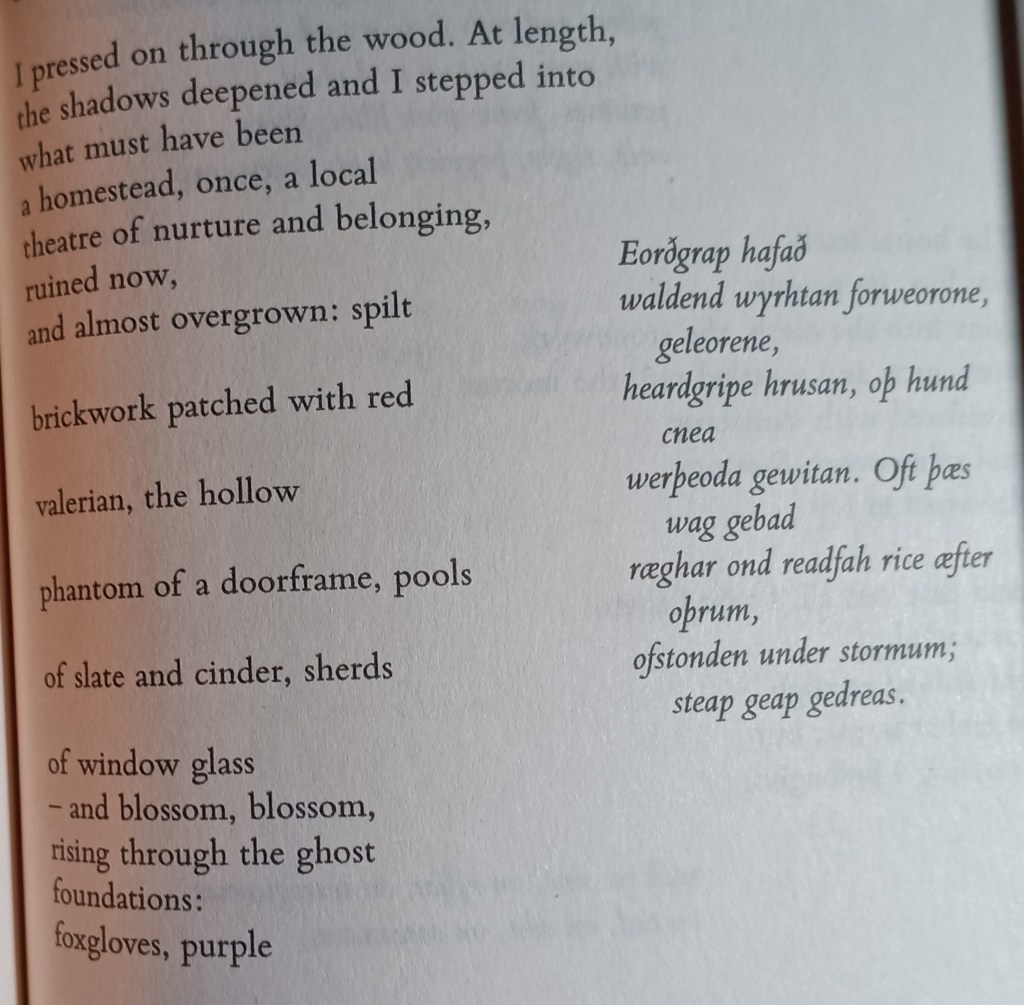

The classic poem of the The Empire of Forgetting has a title recalling the mode of a musical riff on a classical or masterful theme; ‘Variations on “The Ruin”‘. It references a poem in Old English often known in longer title as The Ruin of The Empire but is in its ‘Burnsidian’ variation is about a return to a place thought of as ‘Home after years’ that ought to be ‘land / that should have seemed / familiar’ but like all versions of the ‘canny’ has come to seen ‘uncanny’, changed and depleted, lesioned or fractured through by loss, in which the ghosts of the past are like ‘lost and abandoned’ children (the theme of the novel The Glimmer is recognisable here).

No greenwood here,

just scrub and broken trees,

but something about the light

compelled me, like those TV

crime shows, where the tragic history

is larger than the scene:

depths in the bush where

the missing perfect

their silence, the lost and abandoned

ebbing away so slowly, you could think of them

as ghosts.

Look at the line: ‘The missing perfect’. As we stumble into the line it carries the sense that whole poem has its burden – what is ruined must be what might have been perfect (we read that would momentarily as an abstract noun) but has missed that chance. In the enjambement though we discover ‘perfect’ operates not as a noun (or even adjective) but a verb – the missing can only become more perfect by practicing the silence of their lost state. There is something about this and the who;e poetic passage that I miss in any other contemporary poet – the ability to reference and use the feelings of watching a Gothic TV drama, alongside the evocation of nature and its broken modern counterpart, but it becomes even more like expression of complex truth when it translates and creates a version in lines printed in tandem in a left column of the page (I will photograph this) of a passage from the original Old English of The Ruin. I find even more thrilling that Burnside must have known that The Ruiin could also be The Ruin of Empire (a good poem to seek in a volume called The Empire of Forgetting but appears silently to have neglected that or forgotten that it is the case. In the end everything speaks of things, even titles, fragmented by time. But before invoking the poem as it is in the book look at the section from the Old English, which I give below with two translations, one of which struggles with the semantic forms known as ‘kennings‘ in Old English – unique concepts such as Eorðgrap, for which mortality is a much thinner concept:

The Ruin is a fragmentary poem found in Exeter, Cathedral Chapter Library, MS 3501, the Exeter Book. The poem’s state makes it difficult to translate; the working translation below is suggestive (even speculative) rather than definitive, intended simply to allow you to work through the text with some sense of its meaning and flavour. [7] Old English original fragment Translation 1 (7) Translation 2 (Wikipedia) …. Eorðgrap hafað /

waldend wyrhtan forweorone, geleorene, /

heardgripe hrusan, oþ hund cnea /

werþeoda gewitan. Oft þæs wag gebad / (10)

ræghar ond readfah rice æfter oþrum, /

ofstonden under stormum; steap geap gedreas.……. Earth-grip holds /

The proud builders, departed, long lost./

And the hard grasp of the grave, until a hundred /

Generations of people have passed. Often this wall outlasted,/

Hoary with lichen, red-stained, withstanding the storm,/

One reign after another; the high arch has fallen.The grasp of the earth possesses /

the mighty builders, · perished and fallen,/

the hard grasp of earth, · until a hundred generations /

of people have departed. · Often this wall, /

lichen-grey and stained with red, · experienced one reign after another, /

remained standing under storms; · the high wide gate has collapsed.

What does Burnside make of this passage:

The version in Burnside’s words takes ideas and pictures from the Old English passage(which he italicises parallel to it). It takes, for instance, the Old English ‘readfah‘ (red-stained) rendered in the more explanatory and extended concept and visual picture of ‘brickwork patched with red’, which almost works like a kenning wherein I see red bricks, an unlikely sight for the early Medieval gaze, perhaps (except in a ruin of Roman Imperial basilicas) and somewhat shorn of the early poetry’s suggestion in ‘stain’ of past ruinous violence and blood, though in the run-on we grasp the ‘stain’ of old brick showing through lichen is actually patches of living Valerian flower.

Throughout this passage, I hope you can see ‘ruin’ is compromised as the site of ‘blossom’ and its conjoint colours. It continues, growing out of ‘ghost foundations’:

foxgloves, purple

loosestrife, sprawls

of clematis and Kiftsgate

roses, speedwell, pyracantha,

creeping phlox.

There is a reason though that this is not the end of the appearance of the Old English poem, for it is essential to Burnside’s grasp that the small offerings of childhood memory are perhaps only the remnant of the grandeur Early Medieval poetry sought, but in being smaller are more beautiful. The Ruin seeks the meaning of ‘home’ or ‘house’ (the familiar) in its link to the imperial city (þæt is cynelic þing, / huse …… burg…. recalling that bright city of broad rule – ‘þas beorhtan burg bradan rices’). He uses the whole beautiful passage, including indications of the fragments in which the poem is extant

seah on sinc, on sylfor, on searogimmas,

on ead, on æht, on eorcanstan,

on þas beorhtan burg bradan rices.

Stanhofu stodan, stream hate wearp

widan wylme; weal eall befeng

beorhtan bosme, þær þa baþu wæron,

hat on hreþre. þæt wæs hyðelic.

Leton þonne geotan

ofer harne stan hate streamas

un…

…þþæt hringmere hate

þær þa baþu wæron.

þonne is

…re; þæt is cynelic þing,

huse …… burg…. [7]

Hasenfratz translates this:

looked at treasure, at silver, · at precious stones,

at wealth, at prosperity, · at jewellery,

at this bright castle · of a broad kingdom.

The stone buildings stood, · a stream threw up heat

in wide surge; · the wall enclosed all

in its bright bosom, · where the baths were,

hot in the heart. · That was convenient.

Then they let pour_______________

hot streams over grey stone.

un___________ · _____________

until the ringed sea (circular pool?) · hot

_____________where the baths were.

Then is_______________________

__________re, · that is a noble thing,

to the house__________ · castle_______ [8]

I quibble at Hasenfratz’s choice of ‘castle’ for ‘burg’ , preferring ‘city’, as might be suggested in the Wikipedia discussion of the term and the notion of ’empire’ essential to the poems:

In Old English, the term “burg” (or “burh”) refers to a fortified settlement or town. It originated from the Proto-Germanic word burg-z, meaning “fortress” or “high place”. The term evolved into various forms in different regions, such as “burgh” in Scotland and “borough” in England, reflecting its development into a more general term for a town or city. Burhs were significant in the medieval period, serving as military defences and administrative centers.

Quibbles aside, the point for Burnside is the there is a superior Pleasure of Ruins (I refer to the beautiful 1953 book by Rose Macaulay that you just KNOW that Burnside would know) than gloating over the end of an old empire as you lay down the powers for a new one, a pleasure based on the ruin of the lust for power and empire, for the love of a child for the spiritual found in that which is beautiful in nature and the surprise phenomena of the everyday – like footprints in virgin snow. I hear the love of that in my friend, Joanne’s talk sometimes.

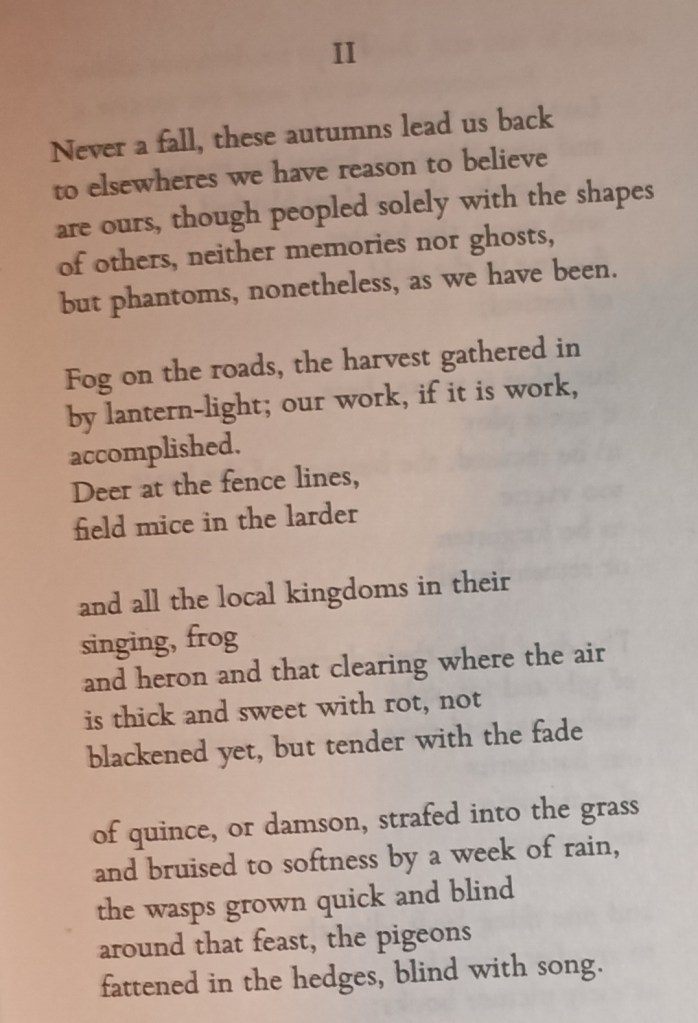

And only here and now can I get to the kernel of my personal interpretation of The Empire of Forgetting as a posthumous volume of the lost and loved John Burnside. The act and process of forgetting need not be conceived as an imperial one, wherein a greater power invests itself into the land and memories of colonised people and shapes all of that into an image of itself – as the Roman Empire did once, as the British Empire did later and as the american proto-imperial project does more indirectly by the imposition of capitalist value systems on populations who cannot gain from such values in mass. In the first lyric of this volume Notes Towards A ‘Devotio Moderna’. Devotio Moderna was a movement much studied by Burnside who read Thomas à Kempis‘s (d. 1471), The Imitation of Christ (c. 1418), as an example of early belief about the wide applicability – in individual bodies and local communities – of the importance of the redemption of Christ (you might remember, in an earlier blog of mine, how he referenced the saint’s ghoulish burial alive). His secular version of this matched the socialist anarchism (or communalism) in his wonderful Ashland and Vine. The second part of the last mentioned poem perfectly embeds the notion of resistance to imperial pretension (in ‘local kingdoms’ not global ones) and a sense of communal ‘belonging’ and ‘self-possession’ that is not appropriative (as empires necessarily are) but about a sense of the familiar made almost spiritual in the surprises of everyday life and beauty, and that accepts loss and decay as transmission through time. One of the most beautiful effects is that he resists seeing cyclic autumns as embraced by the term ‘fall’ (as in American English) because he resists the echo of the fact that humans are fissured by the FALL from God’s grace: [9]

In Burnside’s modern religion there are, as in Rilke’s poetry, angels if no God, and intimations of heaven (or immortality as In Wordsworth) is in death, endings as a young chil left alone and possibly abandoned mught feel them. This is a part of the poem that names the volume that is more than redolent of Gray’s Elegy, but perhaps John Clare too: wherein a child waves goodbye to his mates at evening and where the child Burnside touches a super-nature of the ‘old Gods’;

Barely a wave, then they're gone, till no one is left,

and the dark from the wood closesin on myself alone,

the animals watching, the older gods

couched in the shadows. [10]

And there is a hint here why super-nature never is for Burnside the fundamentally imperialist structure that id monotheism so entrenched in Judaeo-Christian and Muslim tradition, it can’t be a God who rules by imperatives of a singular nature (‘And God said, ‘Let there be light’: and there was light’ Genesis 1, 3) , but of the gradation that enter – not binaries note – when light is accompanied by ‘shadows’ for the latter mix light and dark variously and multiply. Not this from Winter Sutra:

Let there be light and shadow; ... [11]

For fathers, especially when Gods, are cruel – hence the many hidden references to King Lear (including the ‘ounce of civet’ that sweetens Lear’s imagination) but also the ‘wheel of fire’ on which humanity is bound, which Burnside sees as The Memory Wheel, which is the wheel too of the long and never-ending peel of species extinctions:

All afternoon, we listen for the next

extinction, faultlines

spindrift in the blood

of others, and the dream of emptiness

that kept us entertined, when things

seemed plausible.[12]

It is a hard religion where angels share the characters of the children who so often get lost and abandoned in folk and fairy tale as if it were the only way of not growing up and maturing out of our only contact with super-nature in modernity. But don’t ask me to parse these beautiful words for that would be merely an attempt to remove the chill of evil in childhood experience of adulthood as well as joy.

..., children on the road

too far from town

to hope they might be saved

by police work,

or the usual form of prayer;

and those who straggle home are so much

lovelier

for being gone so long

that none of them can enter in the gate

and be resumed,

... [13]

Perhaps the key poem is Listen With Mother (I see it as his Corby line poem),which seems to engage with children, stories. transition and the wonder of changeful instability in time, but is about the fact the some children never felt that they belonged at all. But read that grim and beautifully alienated and finding its gods there – in death and the certainty of supercession by the communal, ‘the lives of others, hunkered between the stations’:

All the way home, we saw it from the train:

land that belonged to no one, a pagan darkness

... [14]

That’s all for now!

Except to talk it over with Joanne who may feel solidity in spirit where I have not the grace given to me to see any.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Robin Robertson (2025) ‘Foreword’ in John Burnside (2025) The Empire of Forgetting Lonon, Cape Poetry.

[2] John Burnside (2025: 32) ‘As If From the End Times’ line 9ff. in John Burnside (2025) The Empire of Forgetting London, Cape Poetry, 32.

[3] Sarah Knight (2015: 177) Bloomsbury’s Insider: The Life of David Garnett London, Bloomsbury Reader.

[4] Ibid: 178

[5] Available in full at: https://livesteven.com/2023/09/22/is-ragnarok-on-its-way-it-is-but-if-we-knew-that-and-were-fully-informed-by-that-knowledge-we-would-be-urging-governments-to-act-and-now/

[6] John Burnside (2025: 20) ‘Variations on “The Ruin”’ line 14ff. in John Burnside (2025) The Empire of Forgetting London, Cape Poetry, 20 – 23.

[7] from Siân Echard (ed. & Trans from Old English) [2025] The Ruin Available online at: https://sianechard.ca/web-pages/the-ruin/ All texts and translations, other than those directly quoted from Wikipedia (where the translation is by Bob Hasenfratz) or Burnside’s variations poem are from this edition.

[8] From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ruin

[9] The following photograph from John Burnside (2025: 3) ‘Notes Towards a “Devotio Moderna”‘ Section II, line 1ff. in John Burnside (2025) The Empire of Forgetting London, Cape Poetry, 1 – 5.

[10] John Burnside (2025: 14) ‘The Empire of Forgetting‘ Section II, line 9ff. in John Burnside (2025) The Empire of Forgetting London, Cape Poetry, 14f.

[11] John Burnside (2025: 7) ‘Winter Sutra‘ line 1. in John Burnside (2025) The Empire of Forgetting London, Cape Poetry, 7.

[12] John Burnside (2025: 10) ‘The Memory Wheel‘Section II in John Burnside (2025) The Empire of Forgetting London, Cape Poetry, 8 – 12.

[13] John Burnside (2025: 27f.) ‘The Elders‘ Part I, line 13ff. in John Burnside (2025) The Empire of Forgetting London, Cape Poetry, 27 – 29.

[14] John Burnside (2025: 41) ‘Listen With Mother‘ Sec. II, line 1. in John Burnside (2025) The Empire of Forgetting London, Cape Poetry, 34 – 41.