What might Gilbert & George mean when they said in 1986 in What Our Art Means (and republished by them in the catalogue of this exhibition in 2025) that it is intended ‘to speak across the barriers of knowledge directly to People about their Life, and not about their knowledge of art’.[1] This blog documents reflection on a visit, and reading afterwards about, Gilbert & George: 21st Century Pictures in the London South Bank, The Hayward Gallery on 22nd October 2025 at 10.30 a.m.

My husband Geoff and our dear friend – almost a daughter, Claire – with the catalogue of this show getting between them.

This is the last of my birthday treat blogs. Now I am 71 officially:

| Tuesday 21st October (Blog for day here) | Wednesday 22nd October (Blog for the day here) |

| 10.30 a.m. Lee Miller’s Surrealist Photography at Tate Britain, Millbank (blog here): Followed by river boat to | 10.30 a.m. Gilbert and George retrospective at the Hayward Gallery, Southbank. Blog here. |

| 2.00 p.m. Theatre Picasso at Tate Modern (blog here) | 2.30 p.m. The Bacchae A new play by Nima Taleghani after Euripides, The National Theatre. (Blog here) 7.30 p.m. Punch Play by James Graham, Apollo Theatre (Blog here) |

It might be worth starting looking at this conundrum about how we get at the meaning of a long-enduring body of art produced over six decades by starting with their key interpreter, who also has an essay in the catalogue to this exhibition, Michael Bracewell, who says that the art of Gilbert & George is ‘beyond any meaningful explanation. And that that’s the whole point’.[2] It is, without doubt, rather bold to make your premise in talking about any phenomena at all, that ‘knowledge’ of that phenomena, far from aiding access to its ‘meaning’ is, in fact, a ‘barrier’ to accessing its meaning. When Gilbert & George continue their 1986 piece, they may concentrate particularly of knowledge about art – of its forms and their history – but there is no doubt that all established knowledge functions, in their minds to stop direct communication between people, and to demand that getting at the meaning of art depends on an elite knowledge base, productive in the twentieth-century, in their words a ‘puzzling, obscure and form-obsessed art’ that they describe as ‘decadent and a cruel denial of the Life of People’.

Nevertheless, bold though it be, it does not stop the art establishment defending the value of the ir ‘knowledge’ by using it to interrogate (the artists’ words) them and their art using such knowledge. Rachel Thomas, lead curator of this exhibition, shows that in her introductory essay to the catalogue that she will attempt to apply some art historical knowledge to get at that precious kernel of meaning in the art, as does the tendency of the interview questions of the by the most innovative art curator of our period, Hans Ulrich Obrist. Let’s take one of the ways Thomas, for instance, uses the terminology of the artists to generate an art-history-friendly knowledge base, seeing in their use of common words, such as ‘screw’ a ‘salient metaphor for Gibert & George’s practice of unearthing and representing aspects of existence such as sex, money, race, faith, death and fear’. All fine and well for terms like ‘screw’ and ‘corpse’ and ‘beard’, all of which are used playfully to describe picture sets, but Thomas only fully elaborates when the word is one honoured by academic knowledge – in the word ‘archaeology’.[3]

The ‘argument’, if that’s the right word, to describe what the current Gilbert and George Exhibition 21st Century Pictures does according to Thomas, is essentially that art has an ethical responsibility to reflect and comment upon the condition of our times through imagery that speaks of the lived values, both validated by national establishments and otherwise, of that nation. Rachel Thomas, in the catalogue of the exhibition, says the relationship between the reflection of salient social values and the artists’ comment on them is that of layers of surface and deeper archaeological layers, although not layers defined by duration of having been laid down. Is that a useful approach to the enjoyment and study of Gilbert & George works?

Of the 2016 quadripartite wall panel art, SEX, MONEY, RACE, RELIGION, Thomas says that its surface imagery, that of each category of its title’s subjects is of ‘the spiritual architecture underpinning the present age’. Thomas moves so quickly from archaeology to architecture that we should guess here that we have educated art history and art commentary on show, especially since neither word is really helpful in her analysis of the art work series, archaeology (but not architecture) only resuming some function in the meaning when she talks about surfaces and depths and their relative contribution to meaning:

The colour schemes of lurid purples and apocalyptic reds are not merely aesthetic choices but psychological temperatures. Backgrounds disintegrate into collaged fragments – currency, foliage and surreal detritus – suggesting a culture slipping from coherence. Within this theatrical chaos, the artists appear as spectral protagonists: suited, bearded, their eyes wide and oddly hollow, their faces – strange, stoic masks – peering out as if behind a veil of dogma. They are haunted presences, registering a kind of spiritual exhaustion beneath the surface bravado. To live through this age, they imply, is to embody contradiction.[4]

As a personal response to the art I find nothing wrong here without some validity, except that it deletes the validating agency of the implications and suggestions found in the art (herself), and replaces it with words that appeal to external and authorised knowledge – archaeology and architecture for instance – without really increasing our sense of how we might share the meaning Thomas finds in the art. For me the art disappears under the barriers of Thomas’ evoked background of education in ‘knowledge systems’. To arrive at a description of meaning that might have described any art since twentieth-century modernism seems to come from a decision not to respond to this art at all but to the tendences of the history of art, and thence to miss the point, that art engages us with meanings but does not summarise those meanings in any terms outside itself – those systems of knowledge our society so depends upon.

How can I then find anything to say myself about my experience, wandering these pictures listening to the input of my husband, Claire and myself – finding access to perceiving things from all three I hadn’t seen previously, but not attempting to calculate from that some overall meaning – indeed, rather the reverse, finding puzzles that make even the need to ‘embody contradiction’ too abstract a statement of what goes on, because too complete as a statement of an experience that keeps going on throwing me off kilter – not just into contradiction but uncertainty of having ever achieved a settled state with the artwork.As we turn a corner of the gallery, we confront:

My response is almost visceral to being a bigot, but equally when I question my response to some of the art to being a ‘liberal’ too. Each position denies engagement, but neither position can be understood without knowing what it feels uncomfortably to be either, where ethical values are concerned. The only useful thing though in this comment on art is that art is about the externalisation of one’s contradictions: bringing out a ‘bigot’ is NOT like ‘coming out’ as queer’ for what is brought out is not meant to be identified with but merely examined, as it too brings out its ‘liberality’ from its bigoted nature. There is no single kind of bigot, nor no single kind of liberal – art is about, then, proliferation of attitudes to Life, none of which are ever resolved into one single identity.

There are obvious artworks which could be used to illustrate this, but I will stick with one that is far from obvious and difficult to parse, and perhaps never is parsed. But let’s dispense first of all, by considering what I said in my last paragraph, that there is, what academics call, an ‘argument either in or to had about this art. All there is are emergent positions that have to find there place in our attempt to find meaning in this singular artist, Gilbert and George. There is only multiple contradictory responses even in one individual and at one time, though the multiplicities are oft increased on revisiting the work, gazing longer or listening to other responses that do not make the mistake, as I think Rachel Thomas does of summarising her view, as if these views could have authority.

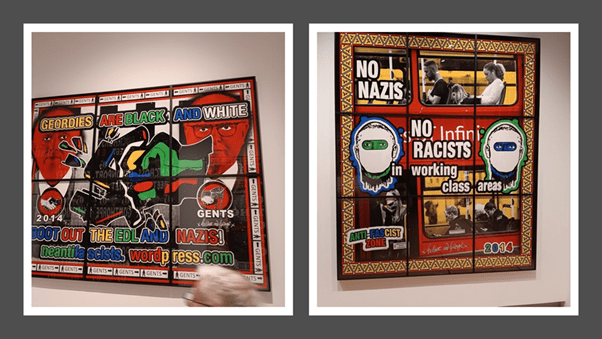

I will start, despite myself with those aspects of the meanings emergent from Gilbert & George artwork that I find most morally challenging, partly because they keep making me return to what they mean, what they are getting at, as pieces that invoke masculinity, race and antiracist and antifascist ideologies, for they are by no means straightforward. Both come from the set they call UTOPIAN PICTURES (of 2014) and both deliberately work with the imagery of Antifascist movements and alliances in London. Below you can see small reproductions of these huge immersive picture, Gents (left) and Anti-Fascist Zone (right). I use both because both have a kind of political incoherence that is hard to locate as the meaning of the imagery and calligraphy used or of the artist’s ‘message’ or ‘meaning’.

The two pictures work entirely differently. Gents puzzles immediately by being framed by a circumnavigation of directions signs to the Gents public lavatories, whilst internally being a fractured and burst explosion of colour, within the frame of a symbol that was that of the SMASH THE NATIONAL FRONT, where a militant fist shatters a swastika, but never so as in such an engaged and violent manner as this. The medallion worn by Gilbert under his collar is, in a manner that rhymes with other left-wing symbolism here with the ‘BLACK AND WHITE UNITE’ hands. But this rhyming also contradicts other messages – the ‘GENTS’ signs are themselves black characters, including the symbol of a man, on a white background. The upper register of the work has the vertical black and white stripes of the Newcastle-Upon-Tyne football team, to which the legend refers: ‘GEORDIES ARE BLACK AND WHITE’.

The political colour iconography becomes entirely undermined, just as does the inclusion in the coloured words of the corporate name ‘wordpress.com’. Now ‘neantifascists’ may rhyme semantically with the reference to the Geordies for it may be the name of a north east (N.E.) Antifascist group arriving for a London rally, but there is no way in which these symbols can be authoritatively read, nor can the redness of artist’s faces emergent out of their monochrome suits. Yet those colour choices and their suggestivity are meant to have meaning, even when that meaning cannot be coherently translated into statement.

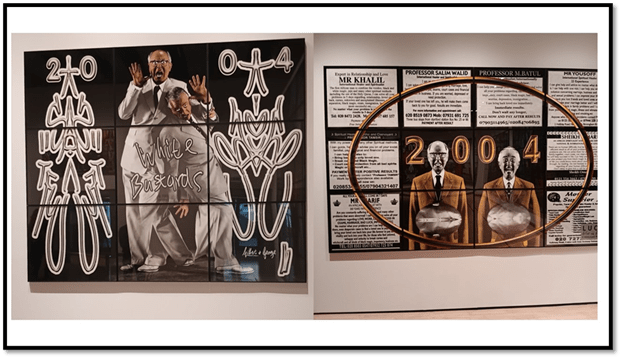

The Stroop effect is the name given to by experimental cognitive psychology to the delay caused in processing incongruent stimuli – the classic example of such stimuli being the name of a colour that is coloured-in with a different colour than that named. In this piece the word BLACK is coloured in green whilst the word WHITE is coloured in white. Whether the Stroop effect is referenced here or not, the incongruence effects will subconsciously effect the processing of the marks here. In relation to Stroop perhaps we mightIn the end I retreat to feeling that the artists have no ‘meaning’ other than the incoherence and more often incongruence of messages that are confronted in such contradictory forms in order to overwhelm the viewer who looks for the comfort of a single meaning. The most difficult of works to process is, in my view, the panel called WHITE BASTARDS in which racial slurs are inverted and reinverted in line with the process of interpretation in which we see the title as an ironic inversion of the more-often-used racist term BLACK BASTARDS, or as an imagination of white vulnerability that disturbs the reality of a culture in which whiteness is privileged. Let me leave my analysis at that.

Severed heads in the Anti-Fascist Zone (right) are a queer form of self -registration for Gilbert & George facial icons – though they are such for you can still see George’s glasses on the blue slit in his white hood but they refuse straightforward meaning just as the white writing on the side of the red bus is obscured by them and unreadable. The political slogans become ambiguous – are they imperative commands or statements of fact. The population of the bus may or may not adduce either reading. It is the more puzzling of the two pictures I have selected from this group. Personal I find myself pulled in to my memory of MNTIFA identity in London from an early period but concerned at the same time that anti-fascist and racist meanings are being distorted and linked to violence. But then, it may be that art has a right to recognise that violence isnot confined to the far right in politics.

Looking at these meanings in play has a similar effect on me to reading Dorian Lynskey in the i paper in 2021 exposing the artists’ High Toryism in the second decade of the twenty-first century:

Contradiction defines them. They are gentlemanly conservatives whose art, like 1995’s self-explanatory Naked Shit Pictures, revels in swear words, bodily fluids and a punkish disregard for social niceties. Therefore the institutions they love — the Conservative Party, the Royal Family, the Daily Telegraph — won’t love them back, while the middle-class liberals they disdain are very fond of them. “Prince Charles is our favourite,” Gilbert says. “I know he wouldn’t like our art.”

…..

… They claim to be wounded by snubs but enjoy telling the stories, like the time Margaret Thatcher’s husband Denis saw their names on the guest list for a Downing Street reception and sighed, “Oh no, not those two.” George smiles. “It’s a good line, no?”

Gilbert chuckles. “It’s funny because we must have been the only ones supporting Maggie Thatcher in the whole art world.” [5]

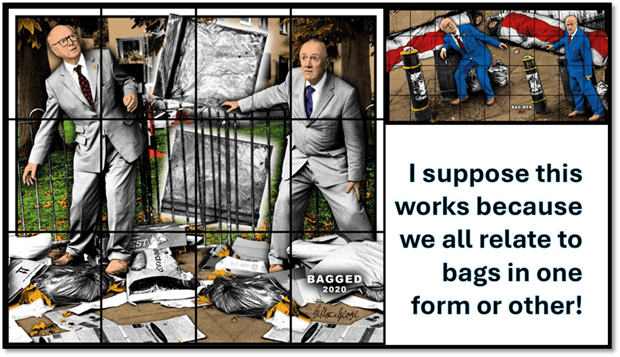

Often the incongruence relates to words that exploit not only ambiguous meanings but ones that have opposed associative meaning in different cultural uses of language, as we shall see when we look at the BEARD pictures, but the word and icon BAG also has this resonance, as in the collage of pictures from the New Normal Pictures below which associate black rubbish bags, drug ‘baggies (of heroin usually), sleeping bags and military body bags in disturbing incongruence of meaning and association.

The above ‘New Normal Pictures’ above are not represented in the exhibition but ‘Bagrave’ (the best, is represented).

In the exhibition these bag crossed associative meanings are strongest in the inclusion of Bagrave, left in the collage below.

I find the ethical work in these works of art more satisfying than any other, more so than those in the Utopian Pictures which expose contradictions in my own history – as a committed London Antifascist – disturbing. But then should not I be disturbed. Speaking to Hans Ulrich Obrist in this exhibitions catalogue, George, and Gilbert in a different way, avoid Obrist’s invitation to link the pictures in UTOPIAN PICTURES to philosophical statements on what ‘utopia’ means in art (Obrist cites Ernst Bloch, Theodor Adorno and Michael Bracewell). Gilbert attempts to deflect from straightforward reference in the title to the idea that it’s ‘our own language … and UTOPIAN PICTURES is a good title, you must admit’, George plays games with a kind of aesthetics of the disengaged by defining utopia as a ‘cultured, cultivated world beyond all unpleasantness’. But where does unpleasantness inhere in these pictures – in anti-fascism/racism or in fascism/racism itself. Sometimes the tendency in the artist to rejoice in platitudes like ‘Culture keeps us safe’ infuriates me, both in terms of the history they refer to and the present time. But then perhaps my fury is ‘uncultivated unpleasantness’ George might respond. In the end, though I do not think George means that art avoids all kinds of ‘unpleasantness’ but that it deflects us from the physical expression of it into reading its complicated ethics in art rather than enacting it in the body in physical violence: ‘The more people read novels or poetry or listen to music, the less likely they are to murder each other. Culture is the saviour’. [6]

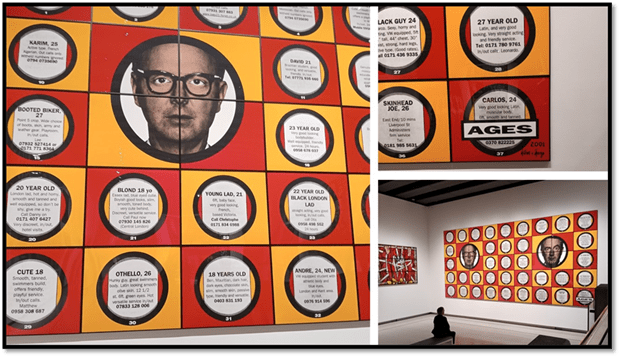

Is George being ironic. In The New Horny Pictures of 2004, in a piece called Ages, is a display of messages in which young men between 18 and 28 (or so they say) advertising themselves for male-on-male sex. The icons of Gilbert and George are set in circles with a quadripartite square, such that the intersection of its internal square boundaries appear like a gun sighting device trained on their face. What are the ethical issues here? Is violence against the queer acknowledged – then whose feelings animate the targeted potentially violent feelings. In many ways the piece animates my own ambivalences about the sex-trade that feeds on youth. Just as the piece Slugged self-slimes the artists.

The most dramatic form of this theme is in a ‘Beard’ picture, God Save The Beard (2016) where sexual suggestions (for the purpose of finding specialist sex between men only VERY RARELY COMPARATIVELY) are the background (there is a companion “Sin” Sational, which is more raunchy and where the specialist sexual search is more ‘out there’. In this one some advertisement statements are quite free of sexual meaning. However all of that is queered by being a characteristic of the obsession with ‘cover’ meanings that is the main point of the BEARD PICTURES.

These pictures exploit the many meanings of beard – hair that is not misnamed if named as pubic (for it relates to male puberty) hair and sometimes used to refer to the cover of manliness used by queer men to hide in public situations – such as the fake girlfriends and wives of queer film stars, such as Rock Hudson, who were called beards. In this picture the beards are not only long and pendulous but also stroked by the figures representing Gibert & George. Within them is a chaos of coloured part figures – male busts from coins, as well as near organic forms. Near the tail end of each beard are advertisements for Condoms and the ‘Big Gay 10K’, some kind of queer fortune-telling website. These beards, and this and in “Sin” Sational are nearer to being phalluses than other beards in this set try to be. Much as I look for redemptive positive meanings about queer lifestyles in these, I find them – and I think this is because such ‘positive meanings’ were always considered to be more like the dogma of a religious ideology than about the representation of the ethical issues in queer lives – as difficult as those in any other lives.

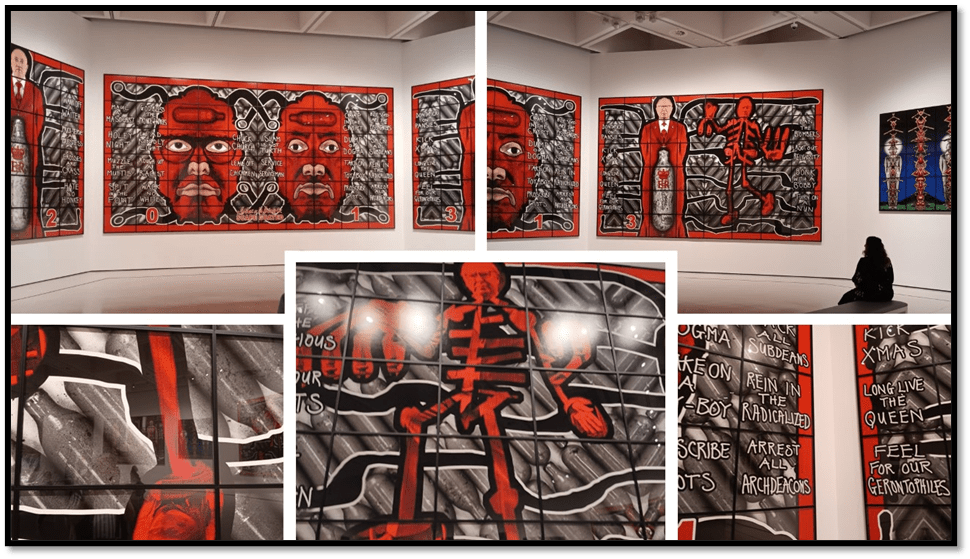

Some very great pictures like the recent SCAPEGOATED, with its central icons of heads with goats (and or devil_ horns and their side panels of re-articulated skeletons with the artist heads but it is hard to see a positive message implied by the title – that, for instance queer men are scapegoated for the observed ills of society – such as the ubiquitous drug canisters in the triptych. For what is powerful in this tryptic are the insect legs-cum-tentacular-webs which tie the figures of the triptych together, and connect them to the random moral/immoral imperatives that overlay the edges of the panels – from nonsense injunctions ‘Maul A Masochist’, ‘Holey Night’, ‘Bonk With A Bobby’ and ‘Sack All Subdeans’ to political injunctions ‘Stop the Stabbers’, ‘Don’t Pick on Pansies’, ‘Ban The Bombers’ and ‘Rough Up a Racist’, and then to the pure ly conservative dogmas like ‘Rein In The radicalized’ and ‘God Bless The Prince of Wales’ (then Prince Charles – a favoured figure of the artists.

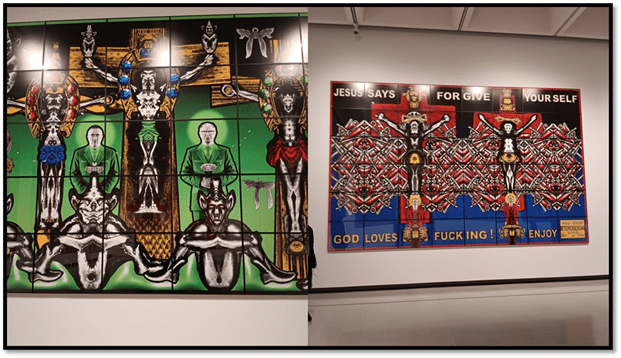

That a kind of nineteenth century anti-clericalism and anti-nationalism also runs through this is also parts of its incoherence: ‘Crap In The Crypt’, ‘Turn on A Nun’ and ‘Ruffle The Religious’. Ambivalent art about religion can sometimes take up much space as in the collage below where Christian and ‘pagan’ ideology mix, often with sexual implication.

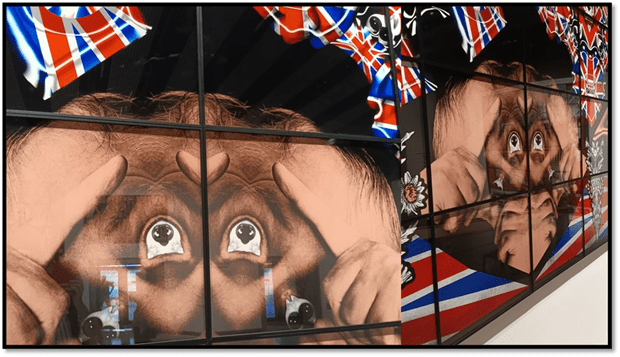

The artist’s hankering after Union Jack flag waving is also complicated with ways of welding images together that deliberatelt associate it with the faked sexual – see for instance how the inversions of facial imagery from the artiststhemselves is turned it shapesthat look queer and sexual.

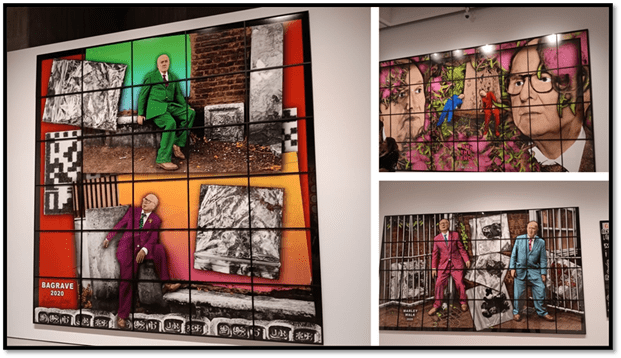

Some later works attempt a kind of queer pastoral I do not understand, as these:

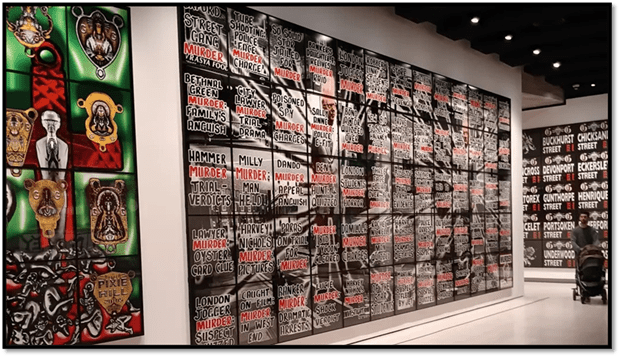

Others use panels to dissect a concept -the relation of crimes against queer men and an association of the streets of East London with public lice that Keep you gazing for hours and never finding anything definitive in them, although Geoff and Claire say to me that the implied narrative of queer murder wall has a political narrative that puts Gilbert and George on the soide of us as activists. I believe them.

There are so many pieces I might discuss but my current undying cold is fuzzing my head, so I will stop here, but just a plea to see this show, and if you don’t go to the Hayward Cofffee bar and find a free showing of the three Day-Tripping films of Gilbert and George, which have spawned books to come out at the end of the show. You will learn more here than reading any account of Gilbert & George, including mine, about the ritual nature of their art and the way its imagery covers something quite dark inside these two men as one artist. Here are some reminders to get you there. Free, apart from buying a cup of coffee to take into the café cinema room with you.

That’s all for now.

With all my love and puzzlement, and some of that artists’ darkness Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Gilbert & George (1986) What Our Art Means’ in Gilbert & George (design) (2025: 54) Gilbert and George: 21st Century Pictures, London, The Hayward Gallery.

[2] Michael Bracewell (2025:21) ‘Gilbert and George: 21st Century Pictures’ in Gilbert & George (design) (2025) Gilbert and George: 21st Century Pictures, London, The Hayward Gallery, 13 – 21.

[3] Rachel Thomas (2025: 10f.) ‘In The Studio of Gilbert & George’ in Gilbert & George (design) Gilbert and George: 21st Century Pictures, London, The Hayward Gallery

[4] ibid.

[5] Dorian Lynskey (2021)Gilbert and George: ‘We were the only people who didn’t have sex with everyone – we weren’t middle class’ – The i Paper (March 02, 2021 1:59 pm (Updated 2:00 pm))available at: https://inews.co.uk/culture/arts/gilbert-and-george-the-new-normal-pictures-white-cube-interview-894192?social_type=MSQA

[6] From Hans Ulrich Obrist (2025: 39) ‘21st Century Pictures: An Interview with Gilbert and George’ in Gilbert and George: 21st Century Pictures, op.cit: 23 – 31