The appreciation of art is not a matter of ‘personal choice’ or ‘favour’; it is a duty. This is so not only for its maker but its reading, for reading is, in part, co-making. Duty, of course, does not exclude personal pleasure if it does exclude banal ideas of choice between pleasures.

The quotation and setting from: https://fixquotes.com/quotes/lets-just-say-that-i-think-any-person-who-aspires-94367.htm

Let’s clear up an obvious potential misunderstanding. We too often use the term ‘art’ to denote visual and plastic (in the sense of being made from manipulable materials) made artworks. But art is not that in the way I use it here, but anything (that appeals to the senses – sound, sight, small, touch, and so on – and their low-level interpretive neural machinery; for the higher levels are much more top-down and cognitive in nature) that is made with some other purpose than its use or exchange value, despite the fact that art, especially pictorial art, is often reduced to evaluations concerning the latter value systems, even if wrapped up in judgements of ‘taste’ and ‘connoiseurship’, both questionable and heavily elitist concepts. Of course art does not preclude the use or exchange value of the product of art but that product alone is not art, other than in its interaction with the processes of its making, which involve the artist’s intentions but also a surplus of the values that feed into the processes of its making. The word poesis in Greek (from Ancient Greek: ποίησις), which is the word from which our term poetry derives0 itself is etymologically derived from the ancient Greek term ποιεῖν, which means “to make”). If art’s products are in part interpretable from the marks that signify the manner of its ‘making, then some part of this making is not essential to those values that spring from its actual usability or sale value but to the attribution of a value system that distinguishes that made with art and that not so made.

The processes of art are in part related to the original maker or artist but also to the person that in receiving the signs of art in the work helps work to complete at least one instance of its process as being made as art. Making or facture is a reflexive process that involves interchanges between all its makers and what is made and can be evaluated quite separately from the evaluation of the work made’s use or sale value, although crude versions of facture are sometimes invoked to justify sale value – such as the innovative techniques of Rembrandt’s drawing skills. But these latter are not the whole of making and indeed Rembrandt’s drawing skills, if we take that example alone, have always invoked the need to the viewer of art to co-operate in the finish of his illusions or representations (however you want to phrase it) of ‘reality’. From the artist’s side, let’s invoke what Patti Smith, the musician, says of her art, as summarised by an online quotation interpreter:

Patti Smith frames artistry as a vocation bound to responsibility. From the moment someone reaches for the title artist, whether through ambition, entitlement, or the tremor of calling, a burden of care arrives with it. … However one enters, the obligation is the same: to steward vision with integrity, discipline, and humility.

Duty here is not dour or bureaucratic; it is a lived ethic. It means telling the truth even when inconvenient, tending the craft with rigor, honoring the lineage of poets, painters, and musicians who cleared the path, and being accountable to those who listen. It resists cynicism and commodification, asking the artist to protect the work from becoming mere product. It demands patience with failure, devotion to practice, and an openness that allows the world to alter the work. /…

…. The duty is to observe clearly, to expand empathy, to give form to what others cannot yet say, and to keep faith with the work itself. In Smith’s vision, the title is not a crown but a charge, and the freedom art promises is earned by the responsibility it requires. [1] (my italic emphases)

But none of those charges of responsibility to the values of making, facture or poesis are unusable for what counts as the responsibility of a reader, or viewer, or hearer, or otherwise sensor, of the artwork, who realises that a ‘burden of care’ comes with reading, viewing and hearing too. We don’t read just to ‘like’ or ‘favour’ but to know the value of what what we garner of the miracle of this made thing that takes on duties above and beyond that of the social and economic surfaces in which it also survives as a product (for use or sale as a commodity).Indeed the idea of ‘keeping faith with the work itself’ is a statement of a thingness of the made that depends on the exchange of belief between it and its maker (and I would add its fit receiver) that its values matter more than in the everyday processes of product, distribution, exchange and consumption.

Indeed for artists, conscious of the duty named by Patti Smith, the cost of art as making can sometimes be much greater than the gain to the artist, in any other way than satisfaction that they are following a path that is much harder to tread than that which is the norm in a capitalist economy (even in state capitalism as occurred under Stalin, for instance, in the USSR), for it demands of you attention that will not necessarily please its audience or cause any of them to make you its favourite. For instance, I came across this assessment of James Kelman as a novelist recently in a blog by Charles E. May and refers a new Scottish literary magazine thi wurd:

The interview with Alan Warner is certainly worth reading, although it might be a bit depressing for the aspiring writer. Warner laments that people just don’t buy enough good new books of fiction and poetry nowadays because they are so expensive, noting for example that he went into Waterstones recently and bought two hard backs by favorite writers and paid fifty quid for them. The sad case for many writers is that they spend two or three years working on a book and then publishers have to remainder them because they cannot afford the storage cost; thus they end up pulped. Practically no writers of good fiction can make a living doing so. He noted that James Kelman, who he called “our greatest living Scottish writer,” only made about 15 grand last year. Like Warner, I also find these facts “depressing and unsettling.” [2]

Alan Warner says audiences don’t just naturally react to the quality of artistry and art in a work, and that the cost of art as a practice in the processes of making is too high in the time needed to be freed to pay for it – whilst you live somehow – whilst the cost of awaiting a ‘fit’ readership for a difficult work (because of the effort put into it) is too great to be borne by the intermediaries of the production of the work, for they cannot realise the monetary value of warehousing costs as one waits. May and Warner find it “depressing and unsettling”, as does Kelman who has said it many times – sometimes obliquely in his art, and who currently cannot find a publisher in the UK willing to finance his art.

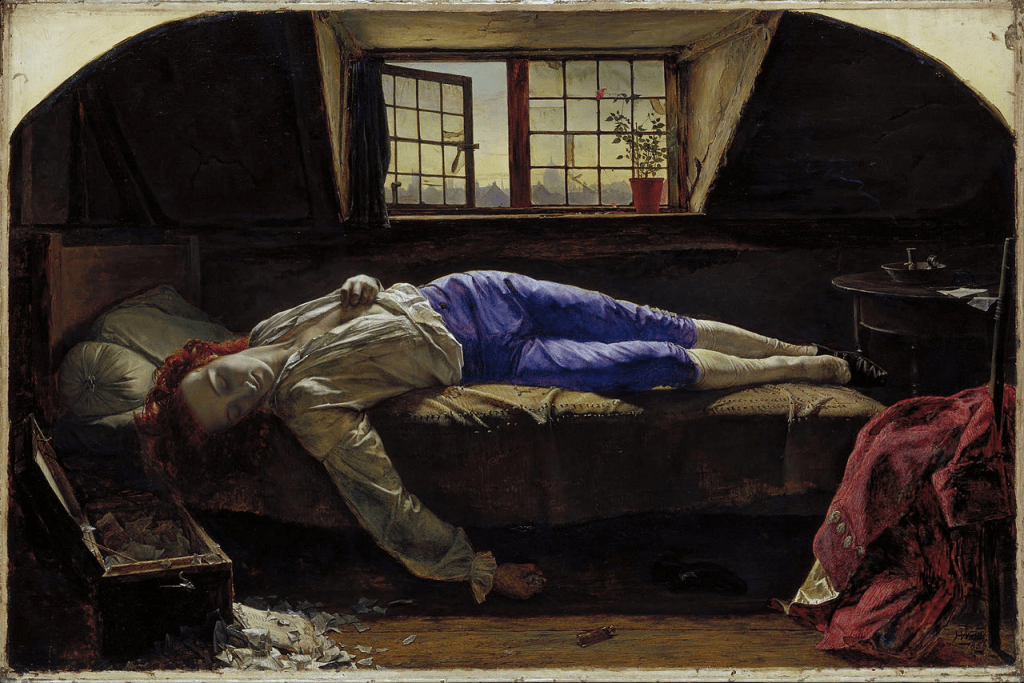

It is this notion that led to the notion of the ‘starving artist in an attic garret-room’, as realised by ‘the English Pre-Raphaelite painter Henry Wallis (1830–1916)’ in his painting The Death of Chatterton. Wallis’ model is the poet and novelist George Meredith, and though people speak ofthis painting as creating a myth, it is firmly rooted in the artists’ involved belief that art was costly and its duties too harsh for a world not willing to merit what has been made to the value at least that would allow the artist to live, as a flower lives – like that on the dead poet’s window sill:

The icon was common enough in the nineteenth-century, and oft, as it did for Thomas Hood, cement the values that fed them as makers (but did not feed them as human beings who must eat material food that they can only buy) and united them to common causes of the suffering, as in his The Song of the Shirt. Readers today may not find much art in Thomas Hood, as the very cruel Dickens did not, but they should recognise that the aspiration is value-driven, in the way connoiseurial taste, or some versions of aesthetic taste, is not. Such ‘taste’ as nothing whatsoever to do with the sense it is named after.

Bye for now

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

_____________________________________

[1] From Fixquotes webpage: https://fixquotes.com/quotes/lets-just-say-that-i-think-any-person-who-aspires-94367.htm

[2] Charles E. May (2015) James Kelman and the “Art,” Not the Social Message, of the Short Story in May on the Short Story (online) Monday, July 13, 2015 Available at: https://may-on-the-short-story.blogspot.com/2015/07/james-kelman-and-art-not-social-message.html