‘The departed are yet to arrive / … / but the roads are all laid out: /’ [1] There is no ideal time to pay more attention to the details past than the death that inevitably defines a ‘life’ and picks out its salient meaning. This is a blog referring to a first reading of Simon Armitage (2025) New Cemetery, London, Faber.

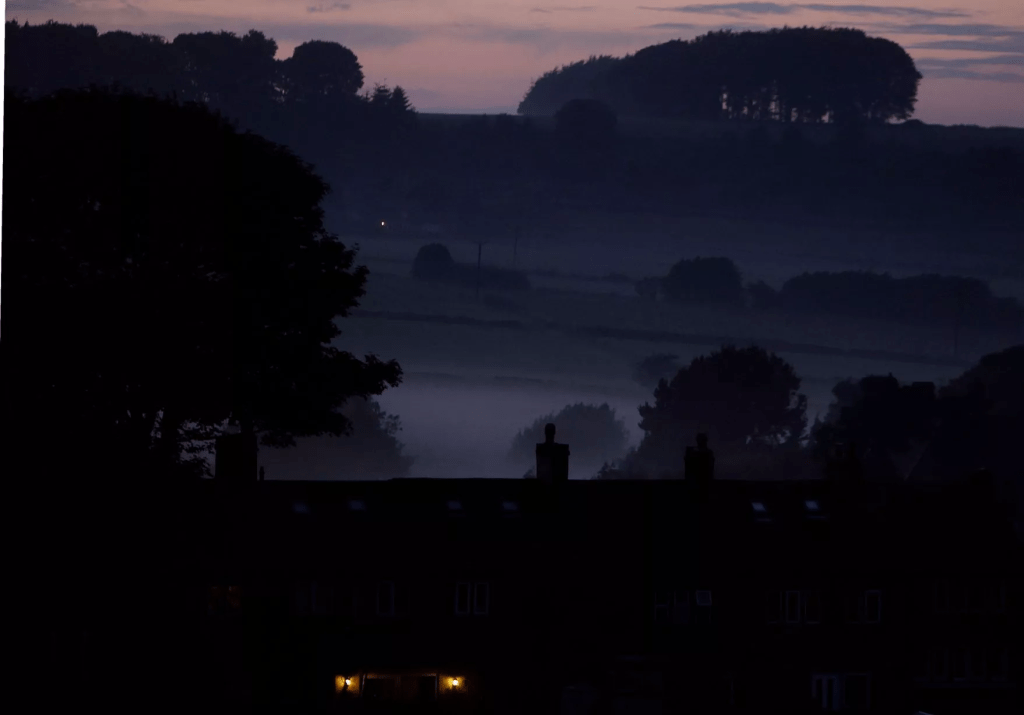

I lived as a teenager in the Council estate known as Roundway (circled in red above) and walked to school at Holme Valley Grammar School (now Honley High School and circled in purple above). From school the terrible cross-country runs went past the site – and perhaps across – the ‘cow fields’ (as Armitage calls them) that have become Hey Lane Cemetery. I used to walk through twilight, dusk into the nights to Castle Hill just beyond the present site of the Cemetery.

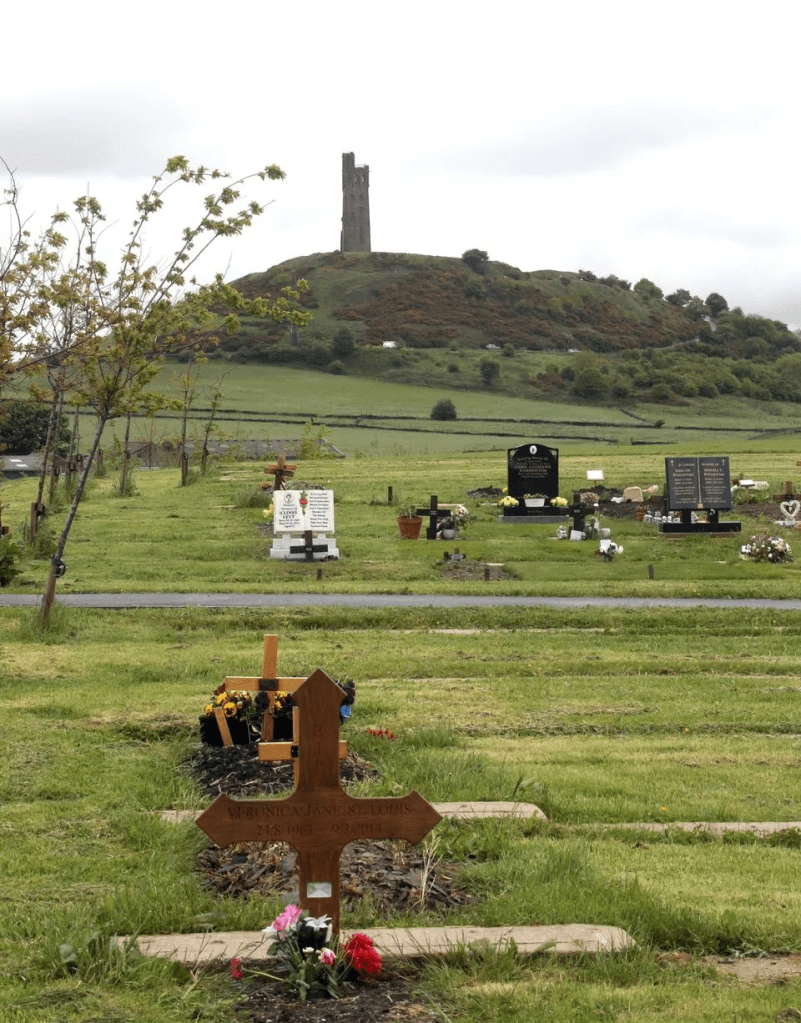

I have followed Simon Armitage’s career and the poetry that marks it for some time, not least because he hails from roughly (very roughly) the same area of Yorkshire as I do, and indeed, from the evidence of the content of his new poems in New Cemetery, must now live even nearer to where I lived when I left the area, first of all to go to university in London. The map above shows the location of Hey Lane Cemetery, the ‘new’ cemetery of which these poems trace the planning, building and use. It shows the area covered by most of the centre of the town Honley where I lived during my teenage (in the council estate at Roundway), and the school I attended (then Holme Valley Grammar School) as well as the New Cemetery which I have never seen. From the poems, it is clear that Armitage lives at Farnley Tyas further up the Honley Road from a T-junction on which Hey Lane wanders away above Berry Brow, passing under the Brigantine earthwork that is Castle Hill (topped by a Victoria Tower since that Queen’s Jubilee) and at Almondbury providing, if your left steep hilly descent to Huddersfield.

These poems deserve more attention but here I use only one of them for my own purposes, although I never observed knowingly so many moths as Armitage does in order to give semi-random occluded titles to these poems. They are truly about these moths he argues, saying the ‘main themes’ of these poems ‘don’t need much explaining’, though he says directly that these themes were the more focused by his ‘dad’s sudden death that year’ and became ‘less abstract this time, driven and informed by personal loss’ (my emphasis). [2] Of course the occasion of the poems was the building of cemetery in a place that looks possibly more rurally remote than it is (just as Brontë settings must have done in the nineteenth century as Elizabeth Gaskell reminds in her first chapter as she arrives by train to research that Life of Charlotte Brontë), its observational research done amidst the flitting of nocturnal moths and hence death was bound in some abstracted way to be in these poems and forming them from within (my favourite sense of what ‘informed’ means in Armitage’s last sentence).

When I think of ‘details of my’ own ‘life’ I could ‘pay more attention to, I imagine my mood as if it were somewhat like Simon Armitage’s. This has dangers for reading these poems as they should be read, but perhaps with poetry that needs to be the case, for no-one would read poetry at all if they could be summed up within one correct reading, free from the subjectivity of the reader, except as an exercise in showing off one’s skill as a parser of texts into its already decided formal parts. Take the poem [Clouded Buff], where the square parentheses tell us that this moth names is not a real ‘title for the poem but one applied afterwards, to show us that there is more than one kind of mortality or extinction consciousness to release from poems reflecting on human intervention into the natural world or as part of the natural world, which in the form of death catches up with all humans in the end. Armitage says: ‘if the poems concern themselves with one kind of mortality, them the moths relate to another: death within nature’. [3]

Clouded Buff Moth

The poem haunted by the rareness of this species is definitely difficult to relate to the moth pictured above: the ‘arrangements of of dazzling complexity and hypnotic intricacy’, let alone translate the ‘codified alphabets or pictograms’ to which Armitage believes the patterns carried by signs and signals across their wings’ into a message about transience, whether either messages of gloom or hope. [4] The poem deals with a ‘mortality’ far too human – the equivalent of the ‘dog walkers, adulterers / and learner drivers’, that used the roads of the cemetery before its ‘plots’ were turned into ‘numbered’ residences of the dead that will eventually fill them. It’s a poem with a kind of dour morality in which the ‘virgin tarmac’ of these roads, as yet without a legitimated purpose, even if purposed randomly for the accidental events of human everyday life, are as ‘laid out’ as a corpse is. Hence the lines I use in my title. The ‘departed referred to therein are have not yet arrived – not because corpses are waiting elsewhere but because these arrivals to come are of persons not yet the dear ‘departed’ , as the dead are oft named. It is a poem warning then of the end of all mortal beings, a ‘cul-de-sac’ we will all meet at the end of those ‘roads’ (of life’ we might say that have been ‘laid out’ for us, if not in all case by Kirklees Council. But the point is I think that it is a terrible think to look back on a life from its termination, were that possible (which I think it is not though it is possible to imagine), and think the ‘details’ of our life have all been ‘laid out’ for us NOT BY US.

It is this abstraction of the fact that the details of our lives – from the patterned events like dog-walking to the secreted opportunities to rebel against formal arrangement that is adultery -are only given sufficient attention if significant in relation to the ‘turning circles and cul-de-sacs’ our road -like lives are when those lives end. Hence the new cemetery has a ‘lychgate’ ( a place for the resting of coffins containing the remains of a human body in tradition) which also ‘doubles as bin store and toilet block’, two other means of easing human WASTE along its journey.

Finished, the cemetery, which I have never returned to see, still seems in photographs quite strangely isolated from modern necessities to cater for the ends of lives nestling under Castle Hill – Brigantine fort and community and phallic memorial for a Queen who went on too long being redundant.

But this blog is NOT a review of Armitage’s poems. Rather it teases out its innovations of his method that I think are a kind of statement of mortality consciousness all poets get round to eventually. Simon Armitage is just over * years younger than myself but the death of a father oft raises the spectre of one’s own mortality – either because yo feel it or think you ought to having survived such influence. The first poem in the volume (of course not necessarily the first written is named [Common Quaker].

Common Quaker Moth

It is a poem that plays with the idea of the death of a poet, whilst undercutting the fact of that death in its run-on lines:

Reader, today

the poet has gone

These lines seem to announce a death with one of the other ways of indirectly making human finales as departures or ‘having gone‘, except that the next line ‘to his shed’, shows us that such synonyms for death were always ways of treating death as it were just ordinary – which, of course it is. Yet most of us are like Hamlet in Act 1 Scene 2 of his eponymous play, we do not want to think the death of ourselves – or those who bear our likeness such as our fathers, is a ‘common’ event, liking to boast that we are all somewhat special and do not spend our lives in common shows of the everyday events of life: ‘I have that within which passeth show‘:

KING. How is it that the clouds still hang on you? HAMLET. Not so, my lord, I am too much i’ the sun. QUEEN. Good Hamlet, cast thy nighted colour off, And let thine eye look like a friend on Denmark. Do not for ever with thy vailed lids Seek for thy noble father in the dust. Thou know’st ’tis common, all that lives must die, Passing through nature to eternity. HAMLET. Ay, madam, it is common. QUEEN. If it be, Why seems it so particular with thee? HAMLET. Seems, madam! Nay, it is; I know not seems. ’Tis not alone my inky cloak, good mother, Nor customary suits of solemn black, Nor windy suspiration of forc’d breath, No, nor the fruitful river in the eye, Nor the dejected haviour of the visage, Together with all forms, moods, shows of grief, That can denote me truly. These indeed seem, For they are actions that a man might play; But I have that within which passeth show; These but the trappings and the suits of woe.

In his garden ‘shed’ become a poet’s study the poet understand that he to has ‘his themes’ but that they have a tendency to escape the common forms of poetry, even his past poetry;

dirty clouds over Farnley Tyas,

an irregular heart,

dry oak leaves

veined with meaning. [5]

Whilst Farnley Tyas may find itself over-accustomed to dirty clouds (it used to rain a lot it seemed in the Holme Valley and surrounding hills), to see that as the first of the poet’s ‘themes’ fills those clouds with tainted meaning, just as meaning still is veined in ‘dry oak leaves’, though veins through which no life-demonstrating liquor will now pass. That ‘irregular heart’ may be the kind of symptomatic flutters that men in their fifties think of so much, it (together with dirty) also paints a picture of a ‘heart’ symbolically unregulated too – perhaps at war with its conditions, or having a history as such. In his introduction he says his curtailed and compacted lyric tercets with ‘short lines’ ‘are more in keeping with my frame of mind and my length of stride in a phase of life where I am less inclined to run away at the mouth or break into a gallop’. [6] Armitage’s end-stopped short-lines are indeed full of slow motion meaning. This poem ends with a ‘morning’ that is clearly stressing its homophonic companion ‘mourning’. But mourning for whom? Fathers? Selves? They tend to blend. This is especially so when our world has become a ‘stripped-back world’ with its bare bones on show, and clearly ‘old’ – from an earlier time.

What I have done with these poems is very little – I truly believe that they are some of the most moving he has written and need a fuller treatment – perhaps in another blog if I feel the urge later, which it is likely I may not. But they are meant to take a dead hand to our prompt question – for there is in truth only one point of perspective from which to pay attention to the ‘details of your life’ – that of your imagined, but inevitable in fact too, death. This is why Dylan Thomas looked at the death of his father and, thinking of his poetry decided to ‘rage, rage against the dying of the light’. From that perspective wee could see if there is anything in those details that is not ‘common’, seeming grey lie the Common Quaker Moth – and if we look closely we shall see that Quaker is less quiet than they seem, sitting in contemplation, but instead ‘veined with meaning’ that once bore that life: ‘arrangements of dazzling complexity and hypnotic intricacy’. Like these unassuming poems shall we say.

Do read them!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

_____________________________________

[1] Lines 4 & 6 from Simon Armitage ‘[Clouded Buff]’ in Simon Armitage (2025: 34) New Cemetery, London, Faber, 34.

[2] Simon Armitage ‘Introduction’ in Simon Armitage (2025: xiii) New Cemetery, London, Faber. xi – xiv.

[3] ibid: xiv.

[4] ibid: xiv

[5] Lines from Simon Armitage ‘[Common Quaker]’ in Simon Armitage (2025: 3) New Cemetery, London, Faber, 3.

[6] Simon Armitage ‘Introduction’ op.cit.d: xiii