Topics are so aery a thing that you are only ever ‘informed about’ them, but as for ‘subjects’: only they can ‘inform’ one.

As so often, this question attracted me not because I have anything substantial to say about it in answer but because so much of its terminology has had importance to me in the past, as part of my education in the associations of literary language: the terminology of interest here are the term ‘topic and the notion of ‘being informed’about’ a topic. In many ways this is because for me both of these terms suggest alternative forms of their expression that may or may not be synonymous with each other: namely the terms ‘subject’ and ‘the notion of being informed by that subject. Could the question be written thus and mean the same thing?

Of which subjects would you like to be more informed?

Let’s start then with the extant issues relating to the choice to be made between the terms Topic and Subject.If you consult your Google AI tools or even common old Google Search you are likely to be referred to a paragraph like the one below:

Topic and Subject are two terms that are often used interchangeably, but they possess subtle differences in meaning and usage. A topic usually refers to the specific area or theme under discussion or consideration, often forming a subset of a broader subject. It is generally more specific and is the central point around which conversation, writing, or study revolves. On the other hand, a subject is a broader field of knowledge or area of interest that encompasses various topics. It could refer to an individual, object, or theme that forms the basis of discussion, study, or artistic representation.

Available with other detail at: https://www.difference.wiki/topic-vs-subject/

Whilst having no objection to this paragraph, or others at the same source, it feels to me that there are broader implications to the choice between the terms, related to the contexts they evoke that that are less easily related than the paragraph suggests, for topics are invoked usually in contexts where the tone of discourse lacks a certain gravity rather than domains wherein we deal with a question in greater depth and with more nuance of interpretation allowed in the process. We find it easier to talk of ‘topics of conversation’ than ‘subjects of conversation’ and would be more inclined to speak of an ‘academic subject’ rather than an ‘academic topic’, though in each case they alternatives could be used. Is that because you can speak of a topic lightly but not a subject. You can study a subject deeply but not a topic. If this is so, it is likely that the term topic is more nuanced a thing than merely being merely one of a subset of topics that together form the category ‘subject’ as our paragraph of differentiation of the terms above suggests.

Why should I think this. I can only evoke writing that uses one or other of the terms and parse them for why those terms were chosen. Let’s take classic examples from the history of the novel form, starting with Jane Austen, who here describes a witty young man, a young unmarried potential suitor who takes it upon himself to charm young unmarried women with his social wit as an asset somewhat akin to his delicious appearance. His name: George Wickham, his destiny to betray the affection of a young woman by a show of insincere attention and eventually destroy her chance of fortune, status or limited independence in the manner of the ‘seducer’ and ‘libertine’ he is shown to be.

Mr. Wickham was the happy man towards whom almost every female eye was turned, and Elizabeth was the happy woman by whom he finally seated himself; and the agreeable manner in which he immediately fell into conversation, though it was only on its being a wet night, made her feel that the commonest, dullest, most threadbare topic might be rendered interesting by the skill of the speaker.

Jane Austen [1813] Pride and Prejudice

A ‘topic’ here is a thing weighed by the example given: ‘only on its being a wet night’. Of consequence indeed to anyone out on such a night but not to the gentlemen and ladies dancing at a ball whose only contact with its material reference matter is their transit, guided by a footman or gentleman acting as a friend, from their traveling carriage to the venue. This is certainly properly to be classed as amongst the ‘commonest, dullest, most threadbare’ of topics but even topics of a more general application are unlikely in this context to rise into the gravity accorded to a ‘subject’, although a proud gentleman, like Mr Darcy, Wickham’s guardian it turns out, who turns away from light conversation in this novel from the get-go, is equally unlikely to flit amongst ‘topics’ – no more likely than the taciturn but gentle Mr Knightley in Emma.

But given a ‘subject’ worthy of them both Darcy and Knightley wax gravely but reservedly eloquent – wiser than they are fluent. Subjects carry weight. Another novelist lets us know this by how he allows the narrative of What Maisie Knew, openly a novel about how a very young uneducated girl comes to acquire conscious knowledge (that which she ‘Knew’) from the point of view of her only lightly informed perspective, the ‘point of view’ which dominates that luscious novel. Much of the novel deals with how, and in what, Maisie is educated – the irony being that those who ought to bear to her academic ‘subjects’ often leave her amongst lightweight topics, which she is unable to understand critically – notably the stuff of adult ‘affairs’, particularly sexual affairs, covered over by romantic topicality – that of the latest ladies novels. Her governess and hence private tutor is Mrs Wix. She is introduced to us a person incapacitated to deal with ‘subjects’ whilst the topics of her talk are outlined without using – but implying that latter word:

They dealt, the governess and her pupil, in “subjects,” but there were many the governess put off from week to week and that they never got to at all: she only used to say “We’ll take that in its proper order.” Her order was a circle as vast as the untravelled globe. She had not the spirit of adventure—the child could perfectly see how many subjects she was afraid of. She took refuge on the firm ground of fiction, through which indeed there curled the blue river of truth. She knew swarms of stories, mostly those of the novels she had read; relating them with a memory that never faltered and a wealth of detail that was Maisie’s delight. They were all about love and beauty and countesses and wickedness. Her conversation was practically an endless narrative, a great garden of romance, with sudden vistas into her own life and gushing fountains of homeliness. These were the parts where they most lingered; she made the child take with her again every step of her long, lame course and think it beyond magic or monsters. Her pupil acquired a vivid vision of every one who had ever, in her phrase, knocked against her—some of them oh so hard!—every one literally but Mr. Wix, her husband, as to whom nothing was mentioned save that he had been dead for ages. He had been rather remarkably absent from his wife’s career, and Maisie was never taken to see his grave.

Henry James [1891] What Maisie Knew

What is clear is that Maisie is being denied a deeper education or induction into academic subjects because of the inadequacy of her teaching by Mrs Wix, who herself goes a long way round to avoid getting into deep subjects, filling the scape with ‘stories’ from the topics best known to her – each ‘romantic novel’ she is currently reading or fanciful versions of her own life story that miss out the hard subjects – the understanding of her real relationship to the now deceased Mr Wix. The word ‘subject’ and ‘subjects’ in their rich variations of meaning and role in the grammar of the sentences they appear in – as ‘subject’ or ‘object’ noun, verb or adjective. But that is a matter for an essay (or blog) on he James novel itself. The point is that the world Maisie is being educated to grow up in and assume knowledge thereof is one which is more likely to become known to her in the overheard shallow topics of adult conversation and curtailed knowledge than from the serious and weighty study of subjects.

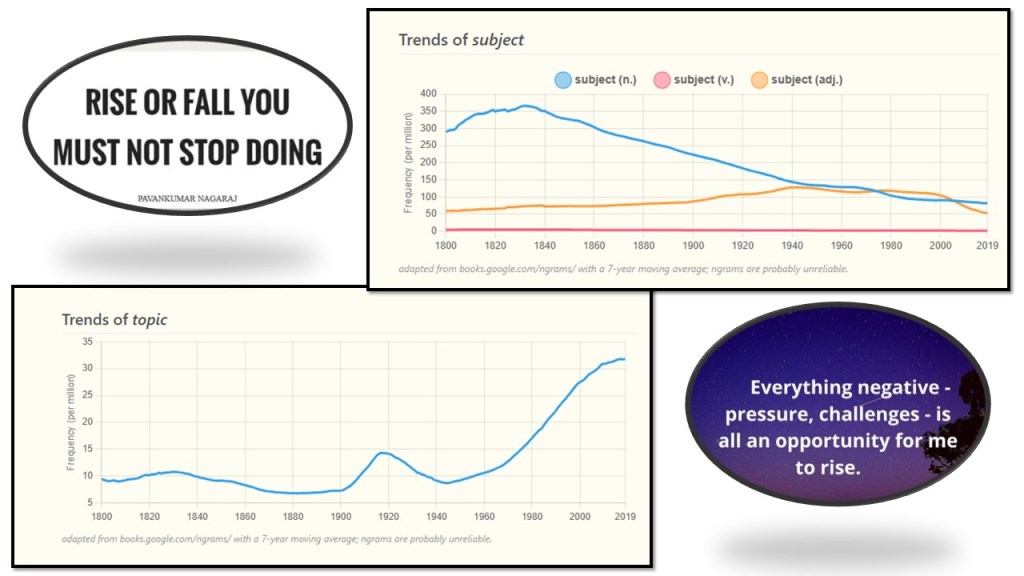

And if we compare the Google n-grams for the two words, it is interesting how one falls from frequency of usage – almost certainly because the democratic word no longer talks of people as ‘subjects’ of a higher power, but perhaps also marginally because education begins to lose its edge of gravity and serious concern. Meanwhile the n-gram for ‘topic’ shows a rise that may interact with the decline of that for subject – for people stop distinguishing their meaning or difference of evaluation of their relative worth.

All that is speculation. And indeed we can’t stop speculating when we look at the difference between ‘being informed’ and ‘being informed about’ something whether topic or subject. Let me start with my own generalisation. For me being ‘informed about’ something implies as trivial a relationship between learning and knowledge as does the reduction of learning to the discussion of topics not subjects. In summing up the relationship of knowing in epistemological terms to the receipt of Information and the act of informing by another I first wrote the following deeply influenced by memory of the teaching in the 1970s of Coleridge ‘s Biographia Literaria by A.S. Byatt as guest speaker in a Literary Criticism seminar, who insisted that the meaning of ‘informed’ at its deepest was a recognition that the thing to be learned is absorbed from without but does not constitute learning until the essential form of the subject to be known in – forms the structure of the learner’s subjectivity. Hence I can now write:

The forming of a thing from within itself is an ideal relation between form and matter, the idea and its realisation. Hence, you can not know something until you are ‘into it ‘ and it is ‘into you’. Knowledge of the ideal form of a subject matter alone ensures we know it a deep and an integral manner not superficially, as might be the case if informed about a thing, in which we have no internalised relationship to it at all.

Byatt never justified her use of the word in the way that informs that last paragraph, but in trying to reconstruct we might look at how the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy discusses the fate of the Philosophy of Information in the Middle Ages, by which the Arabic scholarly world, who preserved the knowledge of both Plato and Aristotle and passed it down to the Occidental cultures of the Middle Ages, largely via St. Thomas Aquinas. In speaking of the fate of Aristotle’s volume Metaphysics during that transition, the Stanford Encyclopedia entry says:

Apart from the permanent creative tension between theology and philosophy, medieval thought, after the rediscovery of Aristotle’s Metaphysics in the twelfth century inspired by Arabic scholars, can be characterized as an elaborate and subtle interpretation and development of, mainly Aristotelian, classical theory. Reflection on the notion of informatio is taken up, under influence of Avicenna, by thinkers like Aquinas (1225–1274 CE) and Duns Scotus (1265/66–1308 CE). When Aquinas discusses the question whether angels can interact with matter he refers to the Aristotelian doctrine of hylomorphism (i.e., the theory that substance consists of matter (hylo (wood), matter) and form (morphè)). Here Aquinas translates this as the in-formation of matter (informatio materiae) (Summa Theologiae, 1a 110 2; Capurro 2009). Duns Scotus refers to informatio in the technical sense when he discusses Augustine’s theory of vision in De Trinitate, XI Cap 2 par 3 (Duns Scotus, 1639, “De imagine”, Ordinatio, I, d.3, p.3).

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/information/#MediPhil

Note that matter receives the idea that will become the essence of the thing ontologically by taking it inside itside itself so that it can inform the thing from the matter that it needs in order to be realised. How easy it is then to move such ontological thought into the question of the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Communion wafer and wine respectively – the materials become informed as sacred entities that are at the same time the real body and blood of Christ. Such thinking is typical of A.S. Byatt as critic (of Tennyson say) or as a novelist, but it is also typical of the manner of the educated scholar, scholar-poet, scholar- novelist, and even scholar-gypsy of the ages that began to disappear in the nineteenth century supplanted by technical education – education made up of nits of configured information (or data), organised into topics and then into subjects in a hierarchy of information. From the latter structure, we can select information about a subject and add it to our private store but we can’t introject it so that it reforms ourselves from within. Information becomes the equivalent of the facts urged as the substance of education by Mr Gradgrind to Sissy Jupe in Chapter One of Dickens’ Hard Times, stuff that you can add to other facts and information but which never is internally imagined as was necessary for Wordsworth and Coleridge (and Dickens) if a thing is to be truly learned and a child or adult informed by ‘ideal forms’ of thought and feeling.

So perhaps now I have at least suggested why I cannot answer this prompt directly – for I hate the thought of a world in which education has been reduced to ‘topics’ (for even reducing it to subjects is a terrible reduction enough) about which the learner accumulates ‘information about’ those topics. No let me be informed in the spirit of Wordsworth where thought enters into the body as its means of transitory being and informs it with eternity (‘with high objects, with enduring things’) that dwells in the body itself – inside the beats of a living heart (and of Wordsworth’ iambic pentameters, as these lines in The Prelude Book 1:

Wisdom and Spirit of the universe!

Thou Soul that art the eternity of thought!

That giv'st to forms and images a breath

And everlasting motion! not in vain,

By day or star-light thus from my first dawn

Of Childhood didst Thou intertwine for me

The passions that build up our human Soul,

Not with the mean and vulgar works of Man,

But with high objects, with enduring things,

With life and nature, purifying thus

The elements of feeling and of thought,

And sanctifying, by such discipline,

Both pain and fear, until we recognize

A grandeur in the beatings of the heart.

IF I HAVE FAILED TO SUGGEST WHY I WROTE THIS BLOG, THEN I HAVE TO FORGIVE MYSELF.

PLEASE FORGIVE ME TOO.

All love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx