Do we give up on one or all of the ‘words that bind us’ at our peril? It might be better to understand why words are multivalent: this is a blog on visiting the Magna Carta exhibition at Durham Cathedral on Wednesday 3rd September 2025. The exhibition runs from July 11 to November 2, 2025.

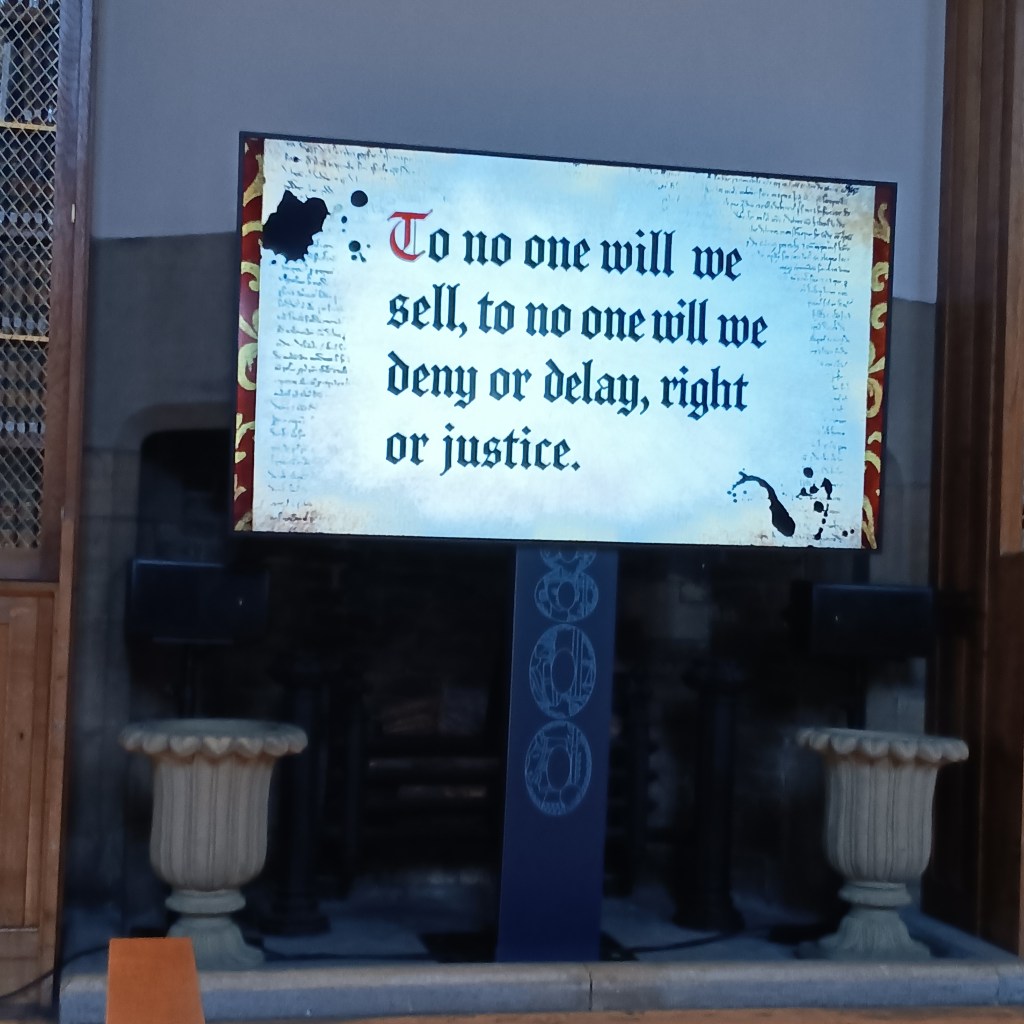

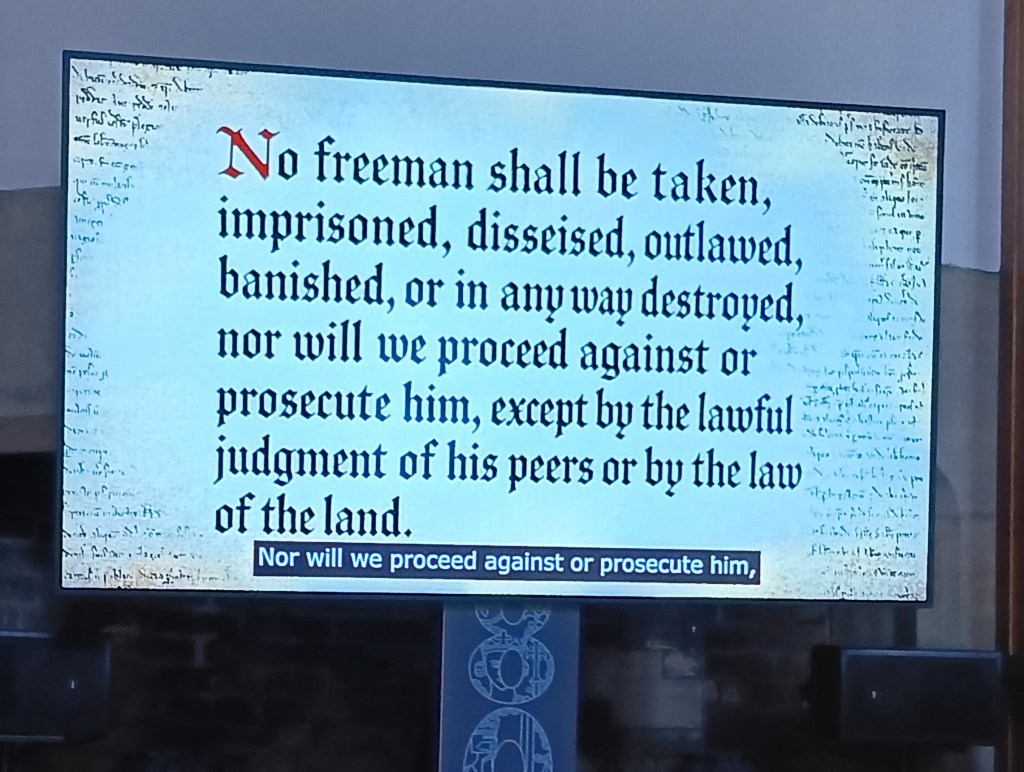

“To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay, right or justice.” These words are often claimed to be the beginning of the belief that there exists a universal principle of the basic rights of each human being independent of the capacity of the individual to in some way reduce the rights of another through turning into a commodity for sale to those wealthy enough to buy it, the military or other kind of force, even violent force, to claim it or as a gift of their superior rights defined by race, nation, gender, sexuality, status, divine right or claim substantiated some other way, such as being a ‘king’ or a superpower. Do we ‘give up’ the use of any such words lightly? Words such as ‘right;’ or ‘justice’. We only have to watch the news each day in the current political moment that to see that their is a current militancy to ensure the denial or delay of rights and justice to certain groups in our societies (currently a class of people classified as ‘migrants’) in the interests of enhancing the rights of more powerful groups, people who identify as the ‘settled’ population of our nation, whether you consider that to England or the United Kingdom. It is not easy to argue a case without discovering that on each side the combatants feel they have the right to a certain interpretation of words like ‘right’ and ‘justice’, perhaps even of the word ‘deny’, For arguments do not use words -0 they live within contested meanings of the same word most often.

Words like ‘right’ and ‘justice’ create a sense of a commonality between animals who have in some way grown to see in the exchange of words between them some categorical forms of values of higher worth than the ability of one or a few to claim superiority over another, let alone many others. Hence, an over-riding theme of Durham Cathedral’s show of the documents which together came to be known as Magna Carta is that of how words come to have a ‘power that binds us’, and variously thought to do so by virtue of any of the following or a combination thereof: an unspoken ‘social contract’, as in Rousseau, or as a categorical imperative that over-rides the powers individual humans seek to wield in order to subjugate others, as in Kant’s philosophy of ethics. At some point I will move on to describe an artwork that takes the title The Words That Bind Us and take this idea further, but, if you can’t work is the description of the artwork, visible in the main transept of the cathedral, even to those who do not wish to pay £7.50 to see the Magna Carta documents themselves.

In some versions, the ties are those we indicate absolute equality in all things, to others only an equality in opportunity or in terms of certain specific domains of rights. In others. Hence, we should not think that just because words are used in common, they indicate a communalism either in the letter or the spirit of that word ‘common’. Recently, forces in England have begun to use the St. George’s flag, for instance, to associate with the common rights of those within a nation against all others, making it an emblem of division between us and them, a them identified with the lust for appropriation of our common weal, figures of projected hate soon turn into objects of fear. Even Nazi Germany venerated community, though with a racial and national implication to the definition of what a ‘community’ might be.

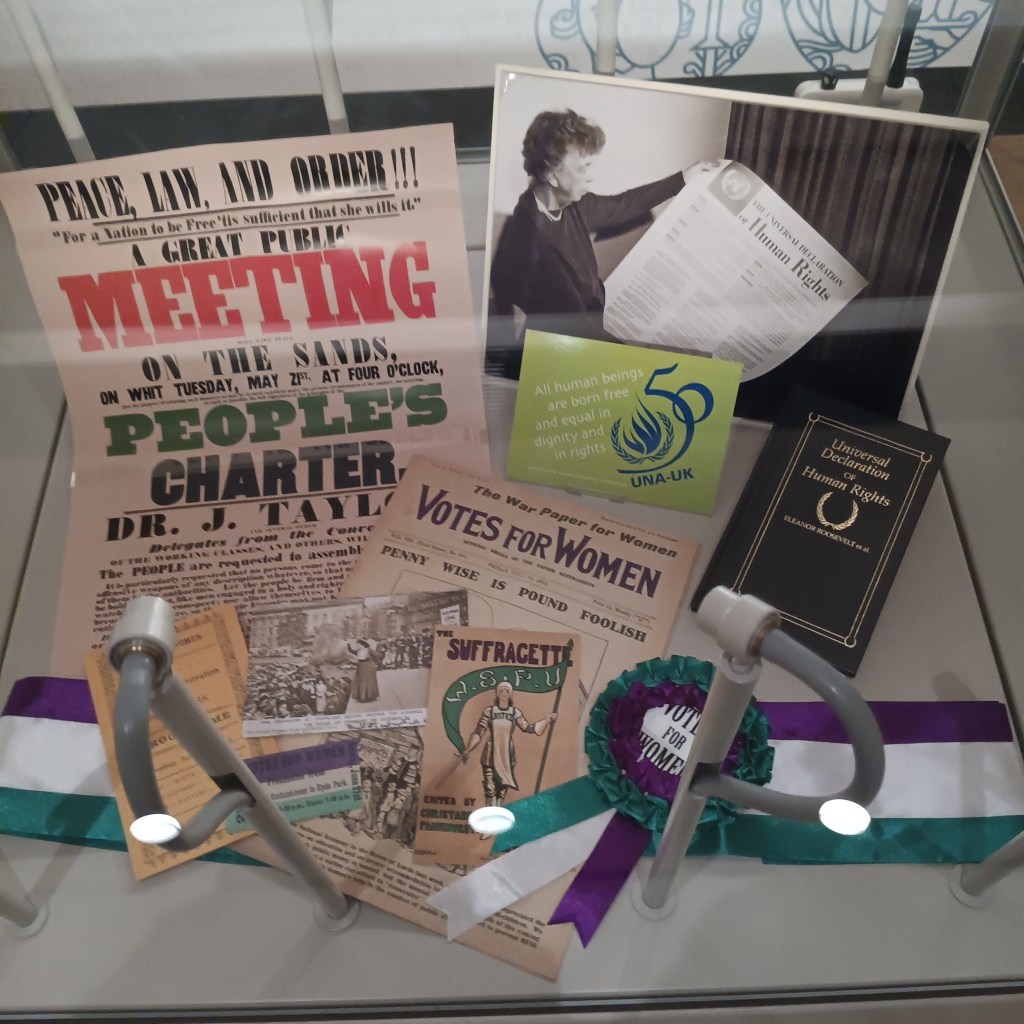

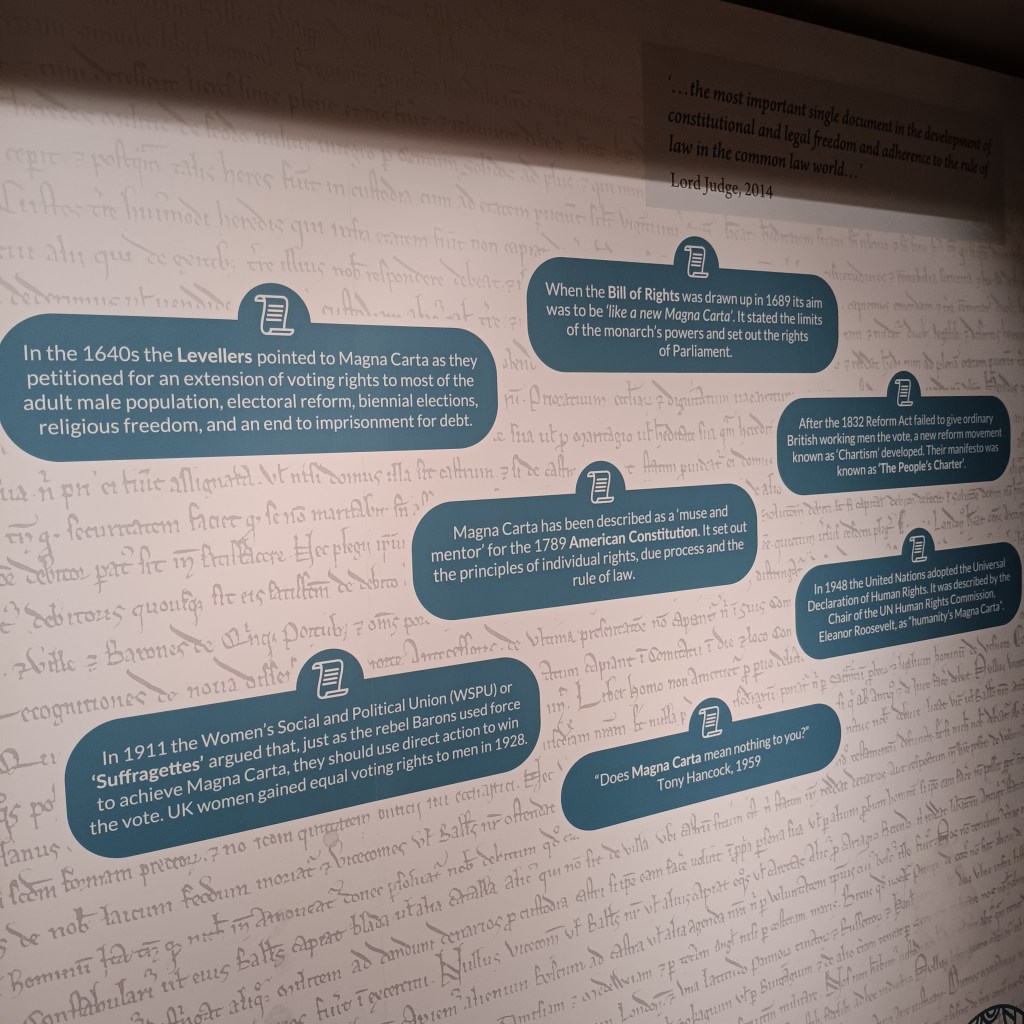

Some uses of the terms of that Magna Carta had stressed were applied to the rights of particular marginalised groups. This exhibition lauds the document as progenitor of the words of. Complex revolutionary and revolutionary texts from Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man, the American War of Independence and age building of a libertarian constitution, the Chartist Movement of the 1840s in England, the Suffrage Movement and beyond to the various Declarations of Human Rights that once seemed sacrosanct. Some evidence that this applied to Black and Brown Lives is perhaps using or merely implied, but such omissions matter.

Omissions matter because the absence of rights is most often also an absence, implicit or explicit, of certain groups and/or individuals from the historical record or the plans for a projected future in the world of social governance. Pain’e’s Rights of Man even, in effect, applied only to males. Right at this moment, there are dark forces at every level of political discourse, taking aim at basic human rights, to life u threatened by threat or terror, to a self- chosen family life, to the right to act in some part of one’s identity refused credence by societal norms. So much is this the case we are told it is not fascists to make a main plank of policy, the eradication of certain rights to certain groups, or their limitation in the manner of the present government. But then, let’s be honest, ‘rights’ of all kinds are bought and sold in such a way as guarantees an inequality in their distribution and very few feel that both rights and justice are not both denied or delayed to many as a result of the operation of power, with whatever motive, as anyone watching that powerful Sheridan Smith drama on ITV currently about the struggle of Anne Ming against laws which denied her and her murdered daughter ‘justice’ will testify, I Fought the Law. And yet that drama uses the Magna Carta as one of its lynch-pins, as in some sense the progenitor of ‘double jeopardy laws’, born to ensure the rights of the relatively powerless but in Anne’s case operating to stop the trial of the declared murderer of her daughter. She has to know about the multi-valence of words in order to address the House of Lords as they consider the use of a repeal of double jeopardy laws with a retrospective effect.

The term ‘freeman’ in the Magna Carta did not apply to women, but the Suffrage Movement by force of pressure on generic uses of the word ‘man’ to mean, implicitly, humankind, even in the word ‘mankind’ made that meaning to shine ought of Magna Carta too. The aim is to make ‘law’ the authority on the limits of all rights and, in that, only because ‘law’ can be subject to change, even by virtue of applying a ‘freeman’s’ rights to women. In fact a freeman in 1215 was meant to apply to the subjects of the king not already enslaved by virtue of unlawfulness, and in the interests of the most powerful of the category of the ‘freeman’, the barons with their own rights over others by natural or other law.

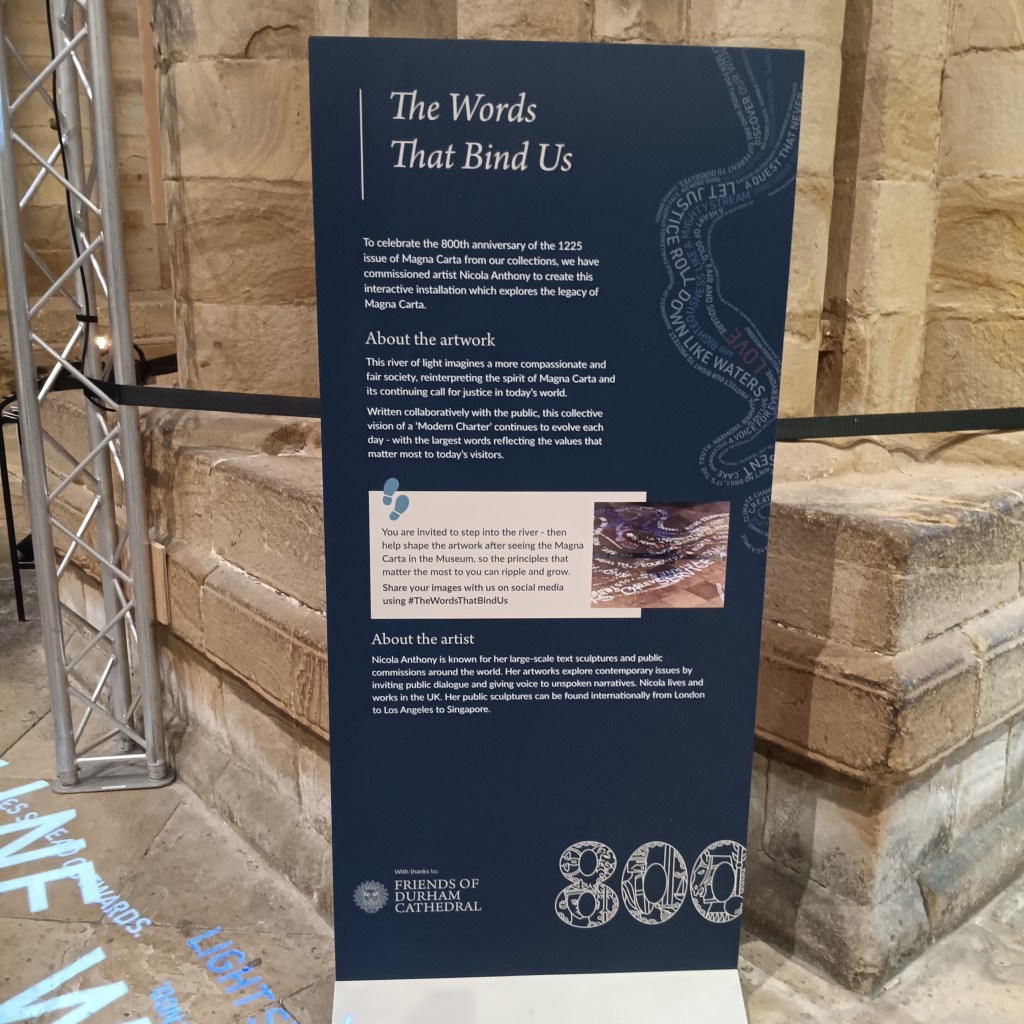

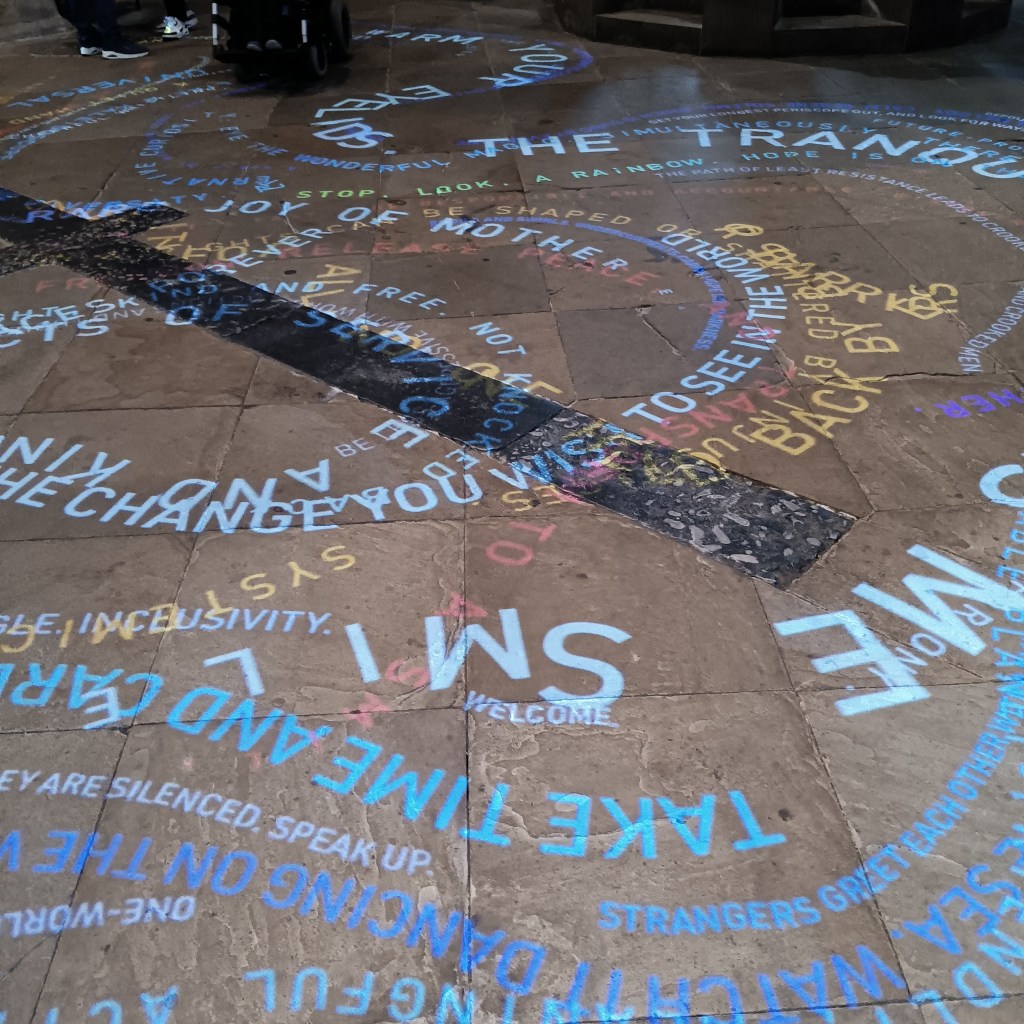

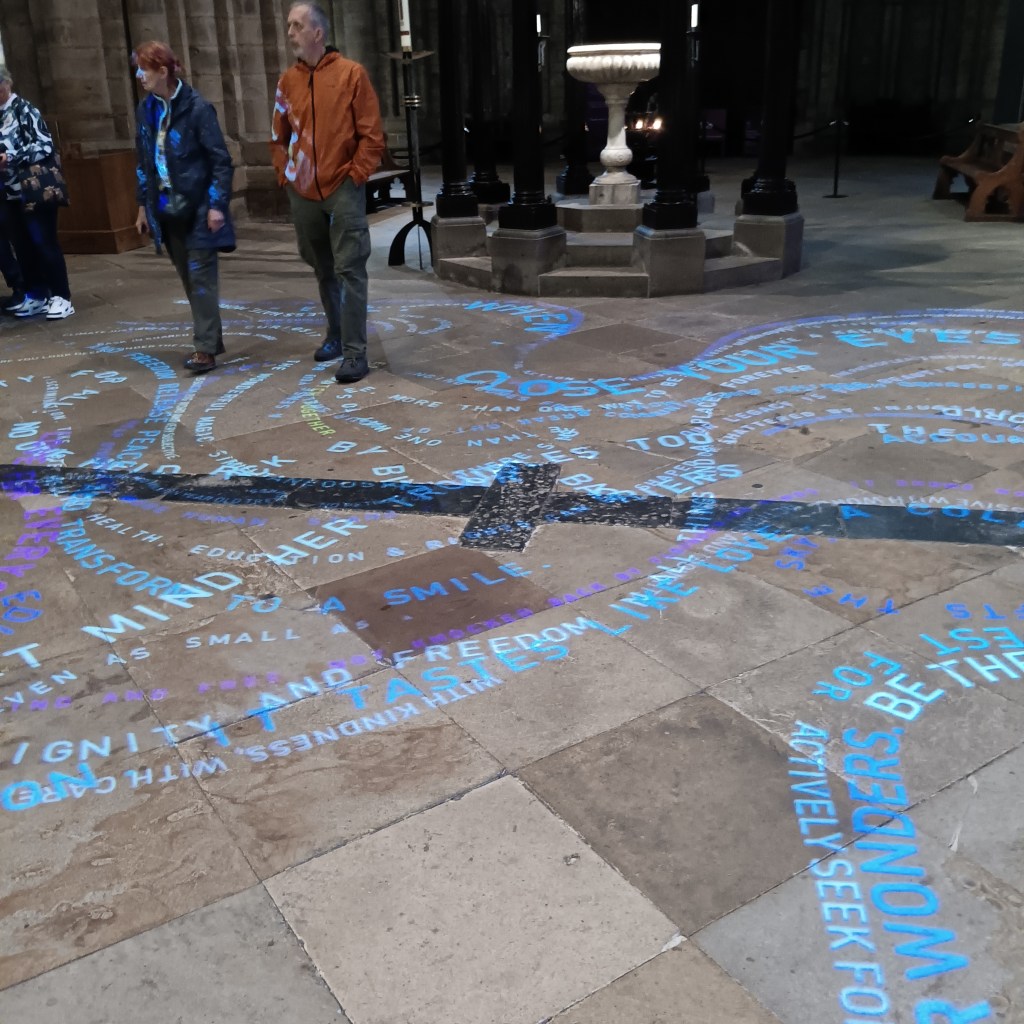

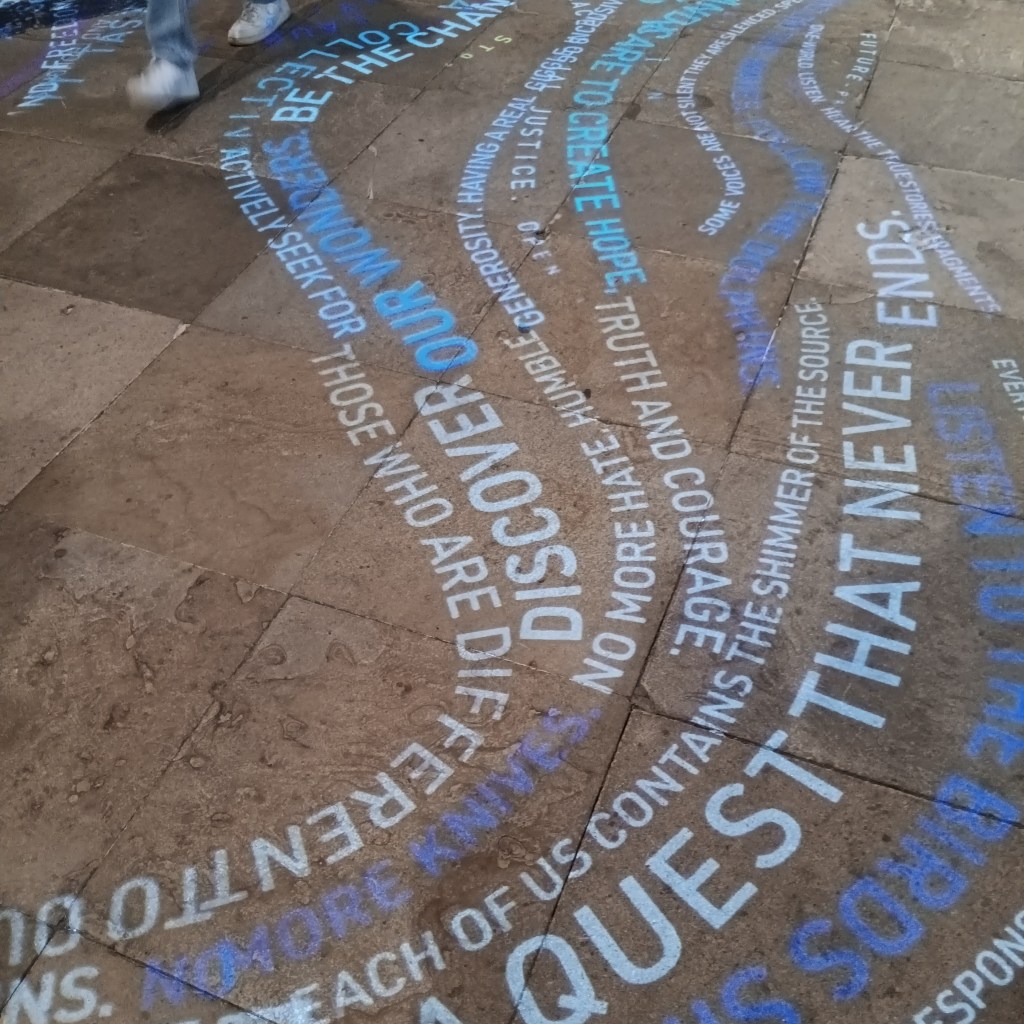

But the Durham exhibition is a multi-faceted one. One note in a description of its exhibits refers to ‘additional features of the exhibition’ thus : ‘The exhibition will include interactive installations and contemporary artworks that explore the themes of freedom and social justice, creating a dialogue between the past and present’. The chief artwork is that by Nicola Anthony and is named The Words That Bind Us, a light sculpture forced of light projected words, using various coloured lighted digital word-images projected onto the floor of the Cathedral. Colour codes differentiate each of many phrases made up of charged words associated with the Magna Carta. Some of these terms in word-strings move in relation to each other – forming snakes of intersecting phrases that curl into and over and into each other, often obscuring each other as they do, especially as some word-strings are much thicker than others.

As you watch them, they struggle to be seen against each other or against the Frosterley marble markings or other distinct darker colorations of some parts of the floor.

But why and how are some word-strings thicker than others. Perhaps only those who visit the exhibition know, having paid their £7.50 (£3.75 for us because we are Art Fund members) for your entry leads you to a last exhibit that controls the ways in which the relative size of the fonts of the word strings are controlled. That last exhibit consists of a list of all the phrases used in the art work and each user of the exhibit can vote for one phrase as having priority for them over others. The number of votes for each phrase determines the size and heft of the font use in the light projection. We might thrill at the democratic intent herebut have to remember that these votes are bought – non exhibition visitors to the Cathedral get no ‘right’ to choose their own favoured word-string.

I wonder if this was part of the artist’s intention to show that for some, who do not buy the right to intervene in her artwork’s appearance, and the relative strength of some word strings over others are excluded from its democratic intent. I wonder. One feeling I had as I watched these phrases move against, around, and sometimes in concord with each other ids that the work’s title The Words That Bind Us is already quite multivalent. To be bound can be a pleasurable thing – we long for bonds that make us attached to others but at other ties we feel bonds imprison us. To be enthralled may be to be interested in something or subject to it. In binding us, do some words ‘tie us in knots’ as sometimes these words do to each other.

None of this is is irrelevant to the exhibition for the purpose of legal documents has always been to represent and enforce by direction to some executive power readers to obey words, whose meanings they must also be bound to agree together. Social bonds lock us in and free us, for they balance powers against each other. And the Exhibition Details show that history is part of this dialectic of debate about which words bind us most and which do not. What we see is that Magna Carta was not that object taught in my primary school – a document that in 1215 at Runymede bound the wicked King John to respect his subjects rather than oppress them, especially those in the North of England, and especially its over-mighty subjects – its barons. In this exhibition we see for the first time in eight years the multiple historic documents referred to as Magna Carta:

- The only surviving 1216 Magna Carta.

- Additional issues from 1225 and 1300.

- Three Forest Charters, which were practical documents related to land and resource management.

The exhibition describes the Significance of the Magna Carta thus:

The Magna Carta, originally issued in 1215, is a cornerstone of British democracy, establishing the principle that everyone, including the king, is subject to the law. It guarantees individual rights, the right to justice, and the right to a fair trial. Notably, three clauses from the 1225 Magna Carta remain in force today.

As a description of ‘significance’ it lacks some heft of its own. But the experience is different. We see it by entering the Museum of the Cathedral – it is for this Museum entry that purchase of a ticket is required.The first room – in part a library is full of wondrous iconic Celtic and other Christian sculptures from medieval Northumbria. It was not these I came to see and have seen twice before, but in that same room is a video installation relating the history of the documents, together with plaques with the relevant history and others with the relevant characters in supersized figures from King John onwards to Henry III. After hissing King John who having signed the manuscript in 1215 wriggled out of it by petition to the Pope to say it had been signed by force of his over-mighty subjects, we see the nine-year-old Henry III with crown askew dependent on his regents.

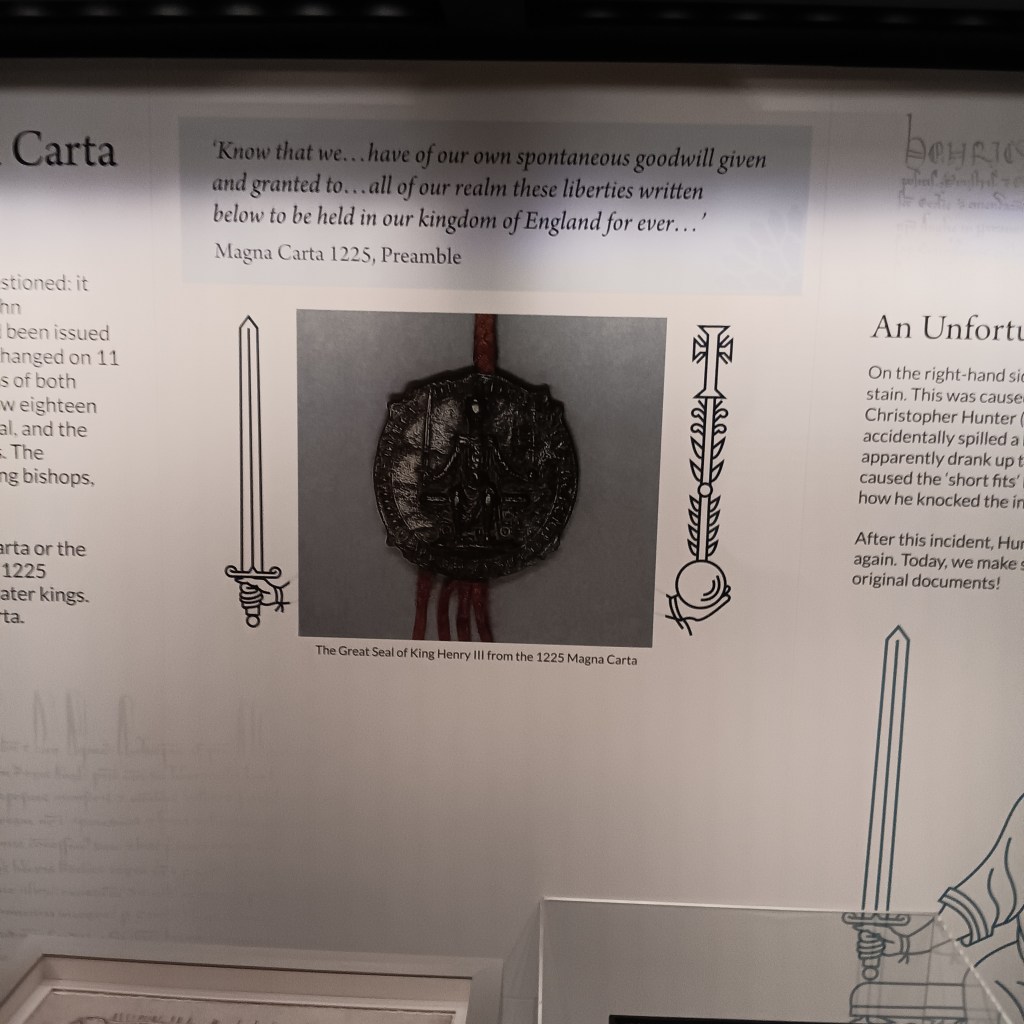

But it is Henry III who will as an adult be hero of the day and eventually sign a revised Magna Carta that starts with a statement that the King is not signing this document by the force of anyone but as the true King of England. Below we see him half-way there in the 1225 version before the final one of 1230. It all gives the drama to the documents we see in the climate conditioned next room where the original parchment documents sit.

However, this is far from the true drama of these wordy parchments, authorised by symbolic seals. What is the implicit drama is that Magna Carta was a contest of wills between its co-creators and their various, and sometimes contradicting interests, The words needed to ‘bind’ the King but to whom – merely to the barons who wanted relief from enforced taxes and wars they were not consulted about. Would not the words bind them too in their local jurisdictions such that the ‘Commons’ were also represented – even if that largely meant ‘freemen’, men who were not ‘serfs’ bound into static subservience? The Church too wanted freedom from the state in its national and local forms and the words that would bind they desired were to free the Church from state interference, even in its financial interests. Pretty shady were some of these rights requested, but expressed in words that were to be interpreted later to speak of the freedoms of ever greater number of people not originally intended to be covered by them. The multivalence of language becomes the path to freedom, though for some it bound freedoms that encroached on others. All that was in theory not practice but in history both matter.

So as we gaze at these documents trying to piece together meaning from script in the strange tongue and stranger calligraphies of past, we are actually seeing the drama that lay behind and under the words, that allowed some phrases to become more prominent than others depending on which interest predominated in these phrases. It is like the Anthony artwork already.

However, some marks relate to even stranger freedoms claimed and their abuse. The document below bears a huge brown stain – the first recorded spill of a scribe’s coffee over his work. Plaques tell the story of this scribe, who, somewhat addicted to coffee and his behaviour showing some effects of him being over-caffeinated (although he may not have understood caffeine was a drug or that he was an addict of it in our terms). The story goes that having spilled his ink on the document, he was deprived of his scribing duties and never allowed again to go near documents which were arduous to make and few in number. It is a joyful moment, so I won’t tell the whole story.

Before we see other modern artworks and finally get a chance to intervene in one, we visit, as I have before the old monastery Kitchen with its enthralling ceiling – somewhat lacking the interest that would have come were the roof chimney that allowed the escape of cooking gases not blocked as it is now.

St Cuthbert’s coffin wasn’t there when I last visited and it is (see below) an interesting sight.

But of interesting relics that attest to the confusion of military and clerical power in the Prince Bishops as head of a holy army guarding the border to Scotland, there is enough. This room is so beautifully lit too.

From there, rturn to the Cloister (if you careful you will see that that too, as well as the Cathedral appears in the guise of the law courts in ITV’s I Fought the Law. Never believe what you see is not masquerading but then so perhaps what we read masquerades too – pretending to free us whilst it binds us in more securely.

But nuance aside, the fear of the moment is greater than ever for the interests of the globally marginalised – those attempting to flee oppressions of all kinds – including ones taking an economic form, for wasn’t even in the nineteenth century the Great Famine in Ireland as manufactured an instrument of power against the marginalised as it is in present use by Israel in Gaza.

Don’t worry then about giving up words you use too often. No! Just know that your use of them reflects many interests at war – it is up to you to make ‘rights’ and ‘justice’ meaningful for all – the many in the all as well as the most powerful few. And since the latter speak loudly enough for themselves, couldn’t we concentrate on those given the poorest hand and with no power of improving it alone.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx