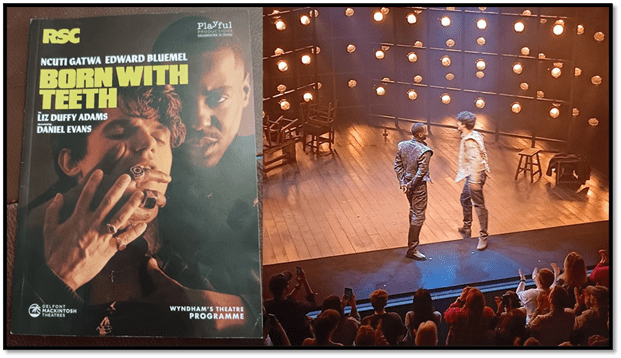

As always I searched for material to illustrate my blogs. Here is an example: Seeing (before reading) Liz Duffy Adams’ Born With Teeth in a production at Wyndham’s Theatre, Charing Cross Road, London on the 20th August 2025, 2.30 p.m.

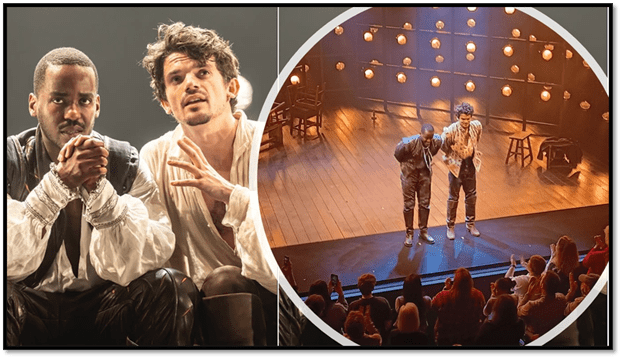

The photographs from the production are taken from: Photos: Born With Teeth starring Ncuti Gatwa and Edward Bluemel – production photos released | West End Theatre (online) (https://www.westendtheatre.com/286272/news/show-photos/born-with-teeth-photos-videos/) . External scenes & Curtain call pictures are min (latter taken from Row B of the Royal Circle).

When I travel to the theatre, I like to know the play – half the fun being how the play is produced from the text into a living embodied enactment of it. That seems to have been the joy of theatre in Greek drama (well tragedy at least), though by the 4th century BCE, Euripides loved to turn expectations on their head, even to the extent that characters in scenes set after the supposed death of mythical characters in the traditional narrative were written, with the explanation that the death was actually of someone or something else, or some kind of trick as in his two plays on Euphigenia with alternative fates for the protagonist. That is clever, if deceitful stuff, but then there could be no theatre, were actors not to play someone they are not – dressed and performing as if they were that person. This is the unspoken knowledge on which Euripides relied – in The Phoenician Women, for instance, when the tragic story of the rivalry between Oedipus’ sons occurs, Oedipus and Jocasta are both still alive, though both died well before the boys were in a position to fight each other – except in child’s play – in Sophocles Oedipus Tyrannus, and in the myths so well known to the audience.

But here I could get no text, though one exists from the American first productions, the text to be used in London was due only to be published on 21st August, the day after I saw the play. I had hoped there would be a pre-publication in London but the bookshops had none, neither did Wyndham’s theatre. I ordered from Amazon in the theatre foyer on my phone but the text is not due to be delivered now I am home only on the 29th August, and even then it may be delayed. However, I felt I did want to write up the play so enthused was I being seeing it. When the script comes, I may write again. After all, I had the programme, as authorised by the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) and had with everyone else in the packed theatre stood to give the most thunderous applause we could at the curtain call.

And the reason I went to see the play was not only because of its reputation as the ‘must-see’ theatrical event of the year, or to see the rather wonderful and beautiful actors (Ncuti Gatwa as Marlowe and Edward Bluemel as Shakespeare) but to see how the play dealt with the various myths that abound in relation to both of the real playwrights who are the subjects and agents of the fictional retelling of part of their lives – based on meetings together in one room (at inns in the first two scenes in 1591 and 1592 respectively) that may not have happened – and for which as events there is not a shred of historical evidence. The last scene is set in Marlowe’s own abode on the supposed day, during one of the many visitations of the ‘Black Death’ plague, on which, in the evening Marlowe is rumoured to have met his death in a pub-brawl in Deptford. Nevertheless, another myth about the playwrights attributes all of the plays of Shakespeare to Marlowe, so obviously that death date is disputed – rightly or wrongly. The various legends surrounding Marlowe’s personal history are examined in his Wikipedia entry.

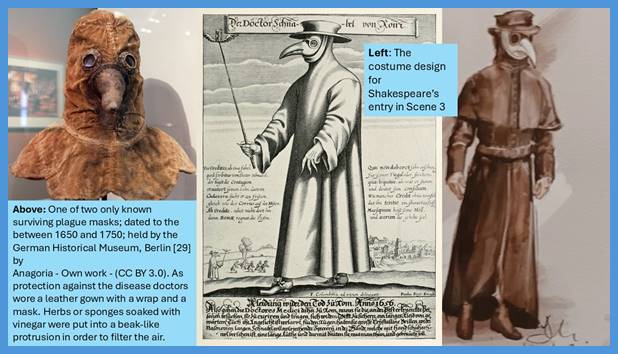

In the play however, setting it without authority in the time of plague when theatres were locked down, allowed Shakespeare to say he borrowed from his doctor his beaked plague doctor costume, in order to visit Marlowe without being noticed by spies.

And therein lies another myth – that Marlowe was a spy, as well as a sex toy, for the courtier, Earl of Salisbury, Robert Cecil and that this eventually led to his murder, by Cecil’s agents. What this play inserts in this myth is yet another one: that Shakespeare himself might have been responsible for Cecil’s belief that Marlowe had become a danger to him. Others historians have felt death from pub brawls needed no spy story to rationalise them. But spy stories emphasise the deceits upon which theatrical role-playing is inevitably based. In both domains, no-one is supposed to be whom they seem to be, and that is rich ground for a playwright to write for those who enact their plays roles in which the characters are themselves acting other roles for different purposes – either for playful or sinister purpose. Shakespeare himself was the master of such plots.

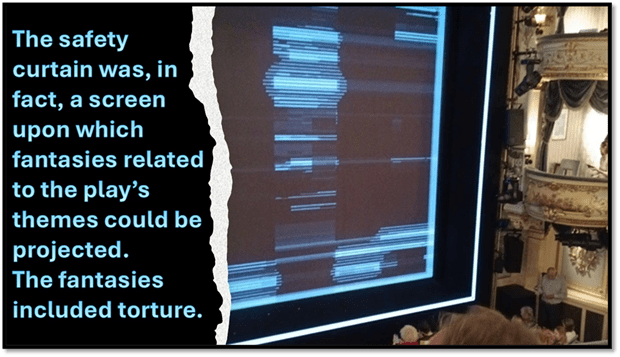

What a web of potential for deceit and playacting! This production emphasised its choice of fact sets by projecting the date for each of its three scenes onto a screen lowered partially over the proscenium for that purpose when necessary. Those dates were:1591, 1592, 30 May 1593; the latter date being that supposedly of his death.

In literary criticism there was and continues to be much debate about the relative value of the playwrights. Even when I studied both at University College I never quite felt there was anything quite like a ‘similarity’ in their dramatic or verse styles that could be the basis of rivalry – the character of their writing and dramatic composition seems entirely different.

And a basic difference in character and expression (and view of what constitutes drama – be it the fascination of watching the progression to glory and downfall of an overweeningly huge single character – as in Marlowe – or the tensions between characters – in the matured Master) seems to be the point in Liz Duffy Adam’s play. This is so (and I will explore it later), even though she accepts the view (or is it myth) that the two playwrights collaborated over the Henry VI plays, perhaps even all three. In the programme different views are expressed about this by scholars. Matt Wolf cites Dr Richard Stacey’s argument that Henry VI Parts 2 and 3 were written first, Part 1 being written when another play was demanded, as a ‘prequel’. This may not be what Adams chooses to believe in her play. In the programme a contribution from Gerald Egan, Shakespeare scholar at Glasgow University, argues that his analysis of word frequency comparisons ‘proves’ (the scare quotes are mine) that all three plays contain sections where words used with more frequency by Marlowe occur than in Shakespeare, and can therefore be confidently attributed to Marlowe.

In the first scene (1591) the authors are working on the scenes featuring La Pucelle, Joan of Arc (from Part 1) about whom they disagree – Shakespeare wishing to find some nobility in her, Marlowe not so. Likewise they discuss (was that in the second scene – I can’t remember where that’s why I need the text) the scenes in which the revolutionary Jack Cade appears, which are in Part 2, where again Shakespeare takes the ‘romantic’ view of the popular rebel in Duffy’s play whilst Marlowe is more the heroic monarchical reactionary – a kind of Tamburlaine of the quill. But the key phrase of the play is birthed after these discussions – the line with the phrase ‘born with teeth’ in it – both saying, though Bluemel/Shakespeare uses the simple phrase first without intention of literary use at this initial point, that, ‘I’m going to use that’ – and both set, in comic pastiche of writing to composing (Marlowe with his long quill shaking in the air).

The resultant lines that use ‘born with teeth’ are in Act 5, Scene 6 of Henry VI Part 3 and are spoken by Richard, Duke of Gloucester (also known as ‘The Bastard’) – soon to become Richard of York and Richard III. These are the lines then that both writers set to write separately in Duffy’s play but the play does not decide who actually is the author of these lines, but even a novice might suppose the author to be Shakespeare (I do).

From Henry VI, Part 3, Act 5, Scene 6 King Henry …. Thy mother felt more than a mother’s pain, (50) And yet brought forth less than a mother’s hope: To wit, an indigested and deformèd lump, Not like the fruit of such a goodly tree. Teeth hadst thou in thy head when thou wast born To signify thou cam’st to bite the world. …… Richard of Gloucester ….. Indeed, ’tis true that Henry told me of, (70) For I have often heard my mother say I came into the world with my legs forward. Had I not reason, think you, to make haste And seek their ruin that usurped our right? The midwife wondered, and the women cried “O Jesus bless us, he is born with teeth!” And so I was, which plainly signified That I should snarl, and bite, and play the dog. Then, since the heavens have shaped my body so, Let hell make crook’d my mind to answer it. (80) I have no brother, I am like no brother; And this word “love,” which graybeards call divine, Be resident in men like one another And not in me. I am myself alone.

The key line here is not that with ‘born with teeth’ in it but the conclusion drawn from it: ‘I am myself alone’. The latter is the underlying thesis about the imaginative genius in contrasting Shakespeare and Marlowe in this play, I’d suggest. The version of Richard in 3 Henry VI and Richard III is the first of the many characters (also often illegitimately born to show their alienation to society and social mores in the name of a self-seeking ‘nature’ – whom the great critic John F. Danby in his great 1949 study, Shakespeare’s Doctrine of Nature: A Study of King Lear, called Machiavels (derived from Machiavelli but with ‘scant resemblance to anything Machiavelli wrote’, as scholars now put it). The classic Machiavel was Marlowe’s and he appears on stage in prologue to The Jew Of Malta .

MACHIAVEL. Albeit the world think Machiavel is dead, Yet was his soul but flown beyond the Alps; And, now the Guise is dead, is come from France, To view this land, and frolic with his friends. To some perhaps my name is odious; But such as love me, guard me from their tongues, And let them know that I am Machiavel, And weigh not men, and therefore not men's words. Admir'd I am of those that hate me most: Though some speak openly against my books, Yet will they read me, and thereby attain To Peter's chair; and, when they cast me off, Are poison'd by my climbing followers. I count religion but a childish toy, And hold there is no sin but ignorance. Birds of the air will tell of murders past! I am asham'd to hear such fooleries. Many will talk of title to a crown: What right had Caesar to the empery? Might first made kings, and laws were then most sure When, like the Draco's, they were writ in blood. Hence comes it that a strong-built citadel Commands much more than letters can import: Which maxim had Phalaris observ'd, H'ad never bellow'd, in a brazen bull, Of great ones' envy: o' the poor petty wights Let me be envied and not pitied. But whither am I bound? I come not, I, To read a lecture here in Britain, But to present the tragedy of a Jew, Who smiles to see how full his bags are cramm'd; Which money was not got without my means. I crave but this,—grace him as he deserves, And let him not be entertain'd the worse Because he favours me.

The facility of shallow but energetically passionate thought – even when the subject is a coldness of spirit as in Machiavel – is characteristic of early Marlowe, and the very thing that Shakespeare (the man who just keeps on writing whatever the temptation not to do so) – much later in his career would challenge in The Merchant of Venice, particularly over the extremity of the antisemitic stereotype of the stage Jew, without (of course) really fully undermining that stereotype.

The thing I think Adams, as a playwright, captures is that there are very different styles of carrying forward one’s exceptional nature and not only that of Marlowe – boastful, narcissistic and, well, just gloriously wonderful. In the play he talks about, as an aim of his mature post-Marlovian drama (a bit evident in Richard III, not identifying his writerly hubris in a play, as Marlowe does, but ‘hiding’ within the play so that one’s true single nature is never revealed in a simple way, especially in a single charismatic character. I will only be able to pursue this further when I have checked my impressions in the theatre with the text.

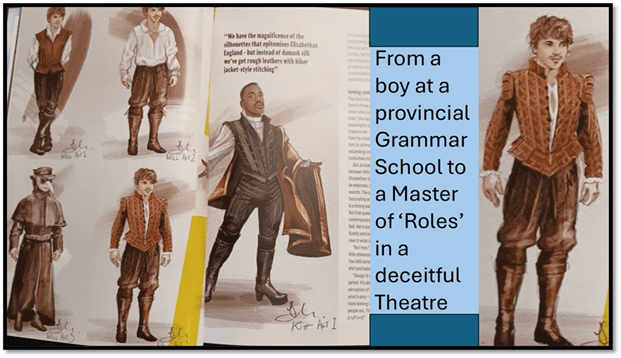

Later I will insist that no-one in the audience need know or think about these issues in relation to the representation of the dramatists as dramatists – the play works with so many reputational issues that are more accessible – not least exploiting the career reputation of Ncuti Gatwa as a mercurial, charismatic and one-off irreverent Doctor Who (without being a fool) or a glorious unashamedly showy Algernon in The Importance of Being Earnest. However, I do want to stress that the author has seriously considered the issues of what kind of dramatists and poets, these two great masters of verse were. I think it is useful, for instance – but not necessary – to know that in this play, Shakespeare is not yet (except in evidently growing aspiration through the play) the poet we know. Had he died when Marlowe did, no-one would rate him as a giant of literature anymore than they would be tempted to distinguish him from any number of ‘minor’ dramatists, some mentioned in the play such as Thomas Kyd, Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, and certainly the inferior of Marlowe. In the play Adams has Marlowe notice how much Shakespeare’s verse matures between 1591 to 1593, using a fairly loose assumption about the disputed chronology of the play and narrative poetry.

Let’s underline where Shakespeare is by showing in a table (whose accuracy and authority I am far from asserting) of what Shakespeare had written by the proposed date of Marlowe’s death and what he had not yet written. As the digital source I use acknowledges, the dates I use for Shakespeare are all heavily contested (even by Adams in the play): ThoughtCo says: ‘The exact order of the composition and performances of Shakespeare’s plays is difficult to prove—and therefore often disputed. The dates listed below are approximate and based on the general consensus of when the plays were first performed’.[1] Gatwa’s Marlowe lampoons the verse of Titus Andronicus and The Taming Of The Shrew, long before these are supposed by ThoughtCo’s dates to be written.

| Plays of Marlowe (with supposed dates of composition) | Plays of Shakespeare (with supposed dates of composition) up to the supposed death date of Marlowe | Plays of Shakespeare (with supposed dates of composition) after the supposed death date of Marlowe |

| Dido, Queen of Carthage, 1585/6, The First Part of Tamburlaine the Great, 1586/7, The Second part of Tamburlaine the Great, 1587, The Jew of Malta, 1589, Doctor Faustus, 1589, Edward the Second, 1592, The Massacre at Paris, 1592, | “Henry VI Part I” (1589–1590)”Henry VI Part II” (1590–1591)”Henry VI Part III” (1590–1591)”Richard III” (1592–1593)”The Comedy of Errors” (1592–1593)”Titus Andronicus” (1593–1594) – mentioned in scene 1 (supposedly 1591) of ‘Born With Teeth’“The Taming of the Shrew” (1593–1594) – mentioned in scene 1 (supposedly 1591) of ‘Born With Teeth’ | “The Two Gentlemen of Verona” (1594–1595)”Love’s Labour’s Lost” (1594–1595)”Romeo and Juliet” (1594–1595)”Richard II” (1595–1596)”A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (1595–1596)”King John” (1596–1597)”The Merchant of Venice” (1596–1597)”Henry IV Part I” (1597–1598)”Henry IV Part II” (1597–1598)”Much Ado About Nothing” (1598–1599)”Henry V” (1598–1599)”Julius Caesar” (1599–1600)”As You Like It” (1599–1600)”Twelfth Night” (1599–1600)”Hamlet” (1600–1601)”The Merry Wives of Windsor” (1600–1601)”Troilus and Cressida” (1601–1602)”All’s Well That Ends Well” (1602–1603)”Measure for Measure” (1604–1605)”Othello” (1604–1605)”King Lear” (1605–1606)”Macbeth” (1605–1606)”Antony and Cleopatra” (1606–1607)”Coriolanus” (1607–1608)”Timon of Athens” (1607–1608)”Pericles” (1608–1609)”Cymbeline” (1609–1610)”The Winter’s Tale” (1610–1611)”The Tempest” (1611–1612)”Henry VIII” (1612–1613)”The Two Noble Kinsmen” (1612–1613) |

The third column of my table includes all the plays we rate most highly as exemplars of Shakespear’s achievement, whilst, to put it mildly, we often make special, cases for honouring those in column 2. By the third scene (May 1593 remember) Shakespeare is ridiculing Marlowe’s new, Edward II, as being too openly only about a king and his ‘boyfriend’ – the point being that when Shakespeare says he prefers hiding in his plays, he means his queer themes too, as they are hidden and semi-conscious in The Merchant of Venice, and in the sex/gender roleplay of many dramas. Again I will look at this again when I get the text. Here, I think we can rest with the fact that this play intends us to see Shakespeare growing into maturity – but that it equates maturity with an overt embrace of the need for secrecy and hiding of one’s nature – as a writer, and especially a queer writer – whether as uniquely attracted to men (as Gatwa’s Marlowe says he is) or not (as Marlowe implies Shakespeare is not thus fully committed).

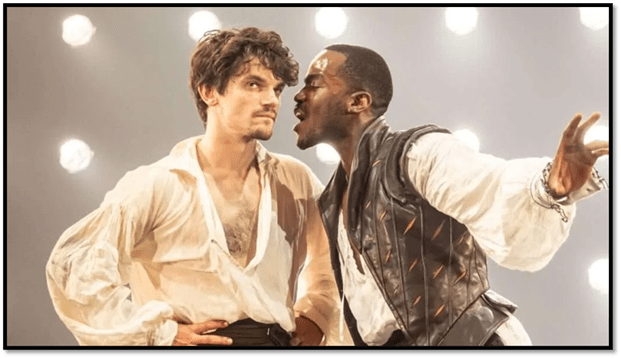

And the play insists that this change has much to do with what Shakespeare learns from Marlowe. Marlowe is in ‘Shakespeare’s face’ for much of the play – insisting on the nature of what he has to offer Shakespeare that is not available from mere writing without passionate experience:

Not only gesturally in his face but speaking his passion loudly in his ear.

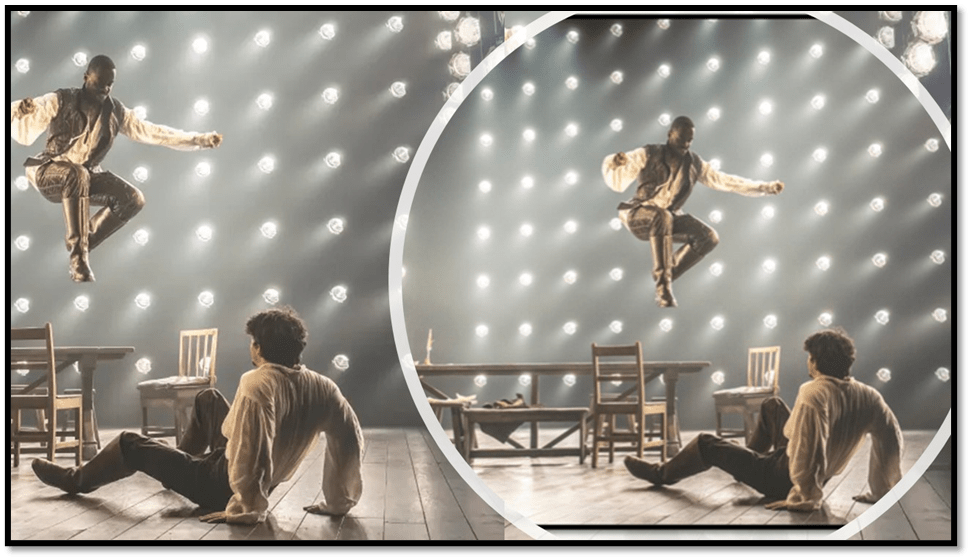

Marlowe constantly tries to tempt Shakespeare from his ‘work’, his writing that his route to maturity lacking the university education of a Marlowe, though Marlowe did that by a scholarship from original poverty, by stripping his torso bare. When even that fails (see picture above), he even tilts the table so that writing is difficult for his companion.

In another picture above, we see him leaning over a table in tight leather pants and later jumping between the Bard’s legs in an aerial leap from a table-top.

However, not only the flexibility of a sexy body is offered, there is also a convincingly played – performed but not necessarily just enacted, tenderness and love between the men and between that the mediation of bodily intimacy, together with shared poetic vision, showing through remarkable actorly employment of abstracted gaze. Take a bow, fellas!

However the other main thing Marlowe teaches is the link between two behaviours:

- Keeping one’s own counsel under cover of other protestations – even lies – whilst covertly removing threats to one’s safety. He will sacrifice he says Thomas Kyd if he can’t sacrifice Shakespeare to keep himself from being the object of surveillance and suspicion – spying in short – by Robert Cecil or other contentious courtiers under the hag that Elizabeth I is described as being – a women jealous for power and maintaining it at all costs, This background of an oppressive court in which spies had an important role is described by Professor Stephen Alford, in a fine little essay in the theatre programme named ‘State of Danger’.

- Ensuring that one’s own survival tops the claims of others for survival. Marlowe in Scenes 1 and 2 shows he will turn Shakespeare in if he needs a scapegoat to save his own skin. Hence in Scene 3 we see Shakespeare doing that very thing to Marlowe by informing on Marlowe when questioned by Robert Cecil himself, and telling Marlowe he will be stabbed that very night (30 May). Marlowe goes to own death as he does to other things he interprets as glorious – like the imperial conquests of Tamburlaine or a kiss from Helen of Troy by Dr Fausus, or a frankness of loving in Edward II.

And everything shows that self-interest is cruel. In a kind of prologue by Shakespeare we see the actors hanging upside down in an imagined Elizabethan torture cell – a likely enough possibility in the Elizabethan state. Tortured expressions by the tortured – are played on a huge screen, somewhat like a safety curtain but divisible into portions. Huge images of Gatwa’s agonised face as Marlowe cover the screen between scenes 2 and 3. When not in use the screen looks like a surveillance data screen capturing digital noise:

And deceit is the necessity of maturity – in developmental psychology, we call it the development of a ‘theory of mind’ where a child learns ‘the ability to attribute mental states to oneself and others, understanding that others have beliefs, desires, intentions, and perspectives that are different from one’s own’. It is the basis of developmental autonomy but also of the role of deception in animal behaviour (it is not only found in human animals or even primates). When you know your mind cannot be read – or not directly – than you can practice deceit, lying or ‘being’ what you want to appear to be by manipulating what others see.

This production cleverly plays with all of these elements of acting and bodily representation. The programme has a fine little essay by Peter Taylor-Whiffen describing the rational of costume design and changes in the play by Jo Scotcher. This goes into the presentation and representation of class issues, including class and status mobility, the representation of sexuality: ‘Scotcher says: ‘The queering of gender then was fascinating and we’re trying to reflect that’. But costume also realises metaphors of cloaking, hiding, dressing up the truth.

The play lived longer with me than many not just because it was masterful in everyway but because it passed the Russell Square test – where suddenly you see the ‘roles people play’ in Goffman’s phrase in everyday life, even crossing the road (Southampton Row).

Moreover, I can’t be done with the play yet – for thought there was sufficient in the acting and production of the whole, I also felt a kind of mystery in the verse that strongly conveyed Renaissance methods – are parts in blank verse. I yearn to see. Moreover, even if not, how was the management of the prose kept so flexible between the ‘high’ and ‘low’ (by which sex is usually indicated but also plodding ‘work’ too), the passionate and the everyday, the tragic and the comic. When the play comes, I will read and consider, and write up if I can, for this is truly living theatre which transcends the places in which it is merely bodily enacted – I say ‘merely’ but there is nothing mere about some actor’s bodies offered to us, as these so generously. The curtain call was well deserved but could have gone on into fuller ovation – but these guys must have been knackered.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Thoughtco.com A Complete List of Shakespeare’s Plays https://www.thoughtco.com/list-of-shakespeare-plays-2985250

One thought on “As always I searched for material to illustrate my blogs. Here is an example: Seeing Liz Duffy Adams’ ‘Born With Teeth’ in a production at Wyndham’s Theatre.”