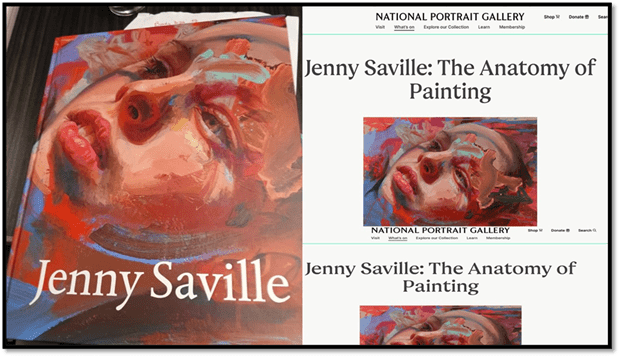

In an interview with Sarah Howgate in the catalogue of the 2025 exhibition The Anatomy of Painting, Jenny Saville says that some part of her decisions and choices of method and technique as a painter is about freeing ‘up time to think about the way I’m applying paint – the mark-making, paint consistency and colour. It enables me to play with the fundamentals of painting’. [1]

In the quotation in my title, Saville is commenting upon her use of photographs as a model for her painting. However, just on the page after in the same interview published in this show’s brilliant catalogue, she refers also to the methods of applying paints in painting that she learned in response to admiring the work of Willem de Kooning. She describes his art process semi-technically but also with intent as a model as ‘dexterity: it was an extensive vocabulary with scraping, dripping and running different colours together’. Eventually forming a ‘bag of techniques’ of her own, she says (in similar terms to those in the title), that they ‘create a freedom in the moment of painting to think about how I am applying the paint, the consistency and movement of my mark-making in building the form. I’m able to charge the paint with sculptural force’.[2]

It is as if these were paintings about art crossing its own internal boundaries – between design and colour, painting and sculpture, work and creation – driven back to the very moment of creating single marks through to the combination of them into what she later calls ‘passages of paint that have the fluidity and movement I was interested in’ when trying to realise a yet inchoate vision, and finally to get to the point where ‘all these sections come together with balance and gravity’.[3] It is like a story that has analysable structure , a language with its grammar, but it is even more like, Saville thinks, a body – a formal mass that has an ‘anatomy’ that can be discussed. This was heady reading for me on the train journey home. Fired I had to talk with a dear friend, Joanne, about all this on a phone call from that train home.

We talked together, Joanne from out of her love of the paintings she had assembled on the internet to see and me on the presumptions of a painting much earlier than those to which Saville was referring in that part of the interview that I quote above. Partly this was guided by the fact that Joanne had loved for longer, much more deeply than I, Saville’s paintings though, because of her mobilisation issues, she has never seen them ‘in the flesh’. The painting her words brought to mind from my fascinations in the exhibition itself is a painting called Trace, from 1993. A ‘trace’ is yet another way that painters talk about their mark-making – a trace that is recoded after the passage of a brush or dripping from it, amongst other techniques.

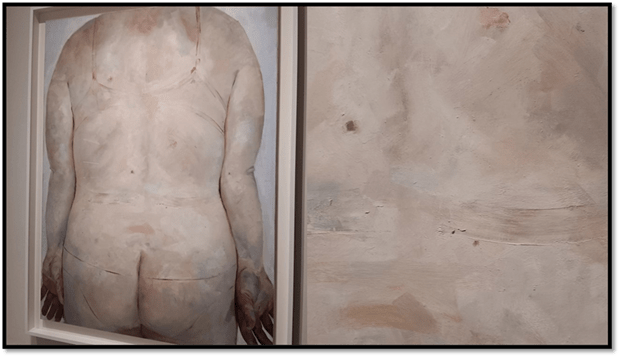

Trace , on first sight is a mimetic painting reproducing the appearance of the back of a woman whose whole torso from buttocks to neck is presented in terms of volumes and masses of flesh contained in a skin so tautened that the clothing removed from it has left a trace of its former architecture, shapings, distortions under pressure of time and boundaries. This mass and volume is also contained in the frame of the picture, as if in a kind of entrapment.

However the interest of Trace as a whole is already intrinsically twofold. A body is a fleshly structure, overlaying a skeletal one and the marks on it or that suggests the pressures internal to its rationale of structure are those of its external boundaries at the skin (including the boundaries at body orifices) and those that impressed upon the skin’s resistance to the flesh’s containment, especially by clothes, but also in body markers of uncertain indication – bruises, warts, spots and cuts. Such marks show the history of a body’s experience in day-to-day living. But to reproduce such marks as a sign of the individuation of the sitter is part of an artist’s representational role. That constitutes the first fold of the art’s interest.

The second ‘fold’ is that each mark, or repertoire of marks within a pattern when the stressor make itself sensed thus on a body, is actually also independent of its representational role and valuable in terms of signalling effects entirely aesthetic or inwardly reflexive about the process of creation by painting. Each becomes the means of articulating outwardly the way marks are independently made on the painting’s canvas or relative to each other (they can be simple relations like contiguity, overlap or overpainting) to create the patterning of various variations of painting technique in its passages of paint. These effects are those of art and perhaps have their own anatomy, one that can be indicated by the way the body can be conceived as a marked subject-matter, bearing the burden of its many experiences.

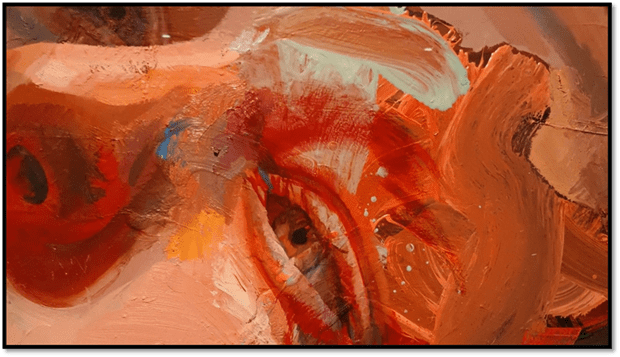

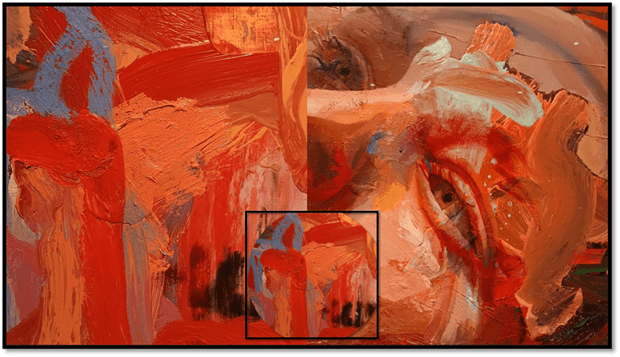

It is difficult to articulate this well, but look at how the painting above uses even simple techniques – in the detail we see how consistent lateral brush strokes are used to convey the stress and pressure caused by the lady wearing an underskirt that hold shape by elasticated containment at the waist, creating a circular lateral mark around the body, but also at the same time liberating this variation of technique and tonal effect. In the anatomy of painting it is no more, or less, an achievement of painting though than the layered impasto effect that creates the look of a mole or wart on the sitter’s back above that band. Meanwhile, the containing strain of her knickers have created something best described by marks at her buttocks that are thinner and require a more defined drawing, rather than painting.

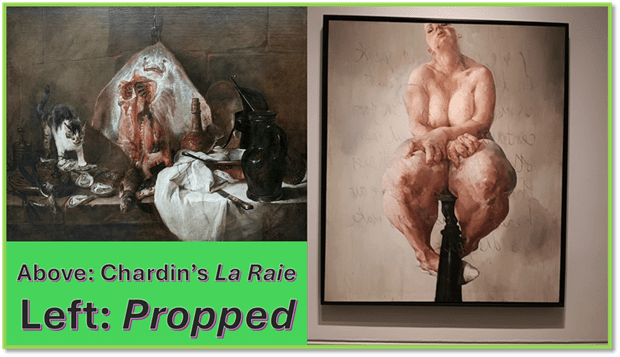

Perhaps, in the catalogue, John Elderfield, expresses it in comparing Saville’s Propped (1992) with Chardin’s La Raie ([The Skate] 1725 – 6 ) in the words of Denis Diderot: it was “a disgusting, repugnant picture” but was also a pleasurable demonstration of how to “salvage objects through sheer talent”, which he sums up in his own words thus, saying that the perspective (bottom -up) puts the viewer in a ‘position, where the picture, as an imitation, may be painful to see, while the painting of it, if not quite pleasurable to see, is so extremely compelling of our attention that we do not want to look away’.[4]

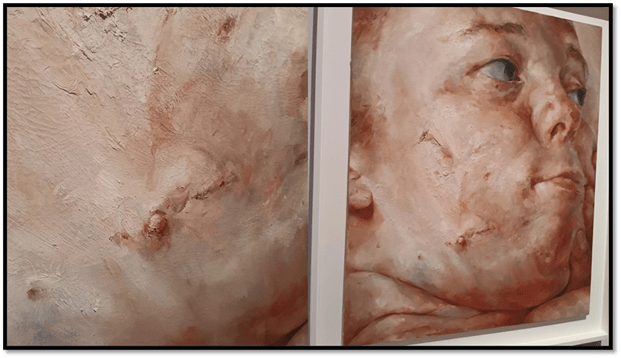

But marks in these paintings are not always related to more immediate stressors – like overtight clothing – but can also be the product of developments in the skin that have different relationships to causation by organic and life-duration-stress origins, such as that ‘wart’ above’. These include other skin ‘blemishes’, a mark on the face, often negatively evaluated by viewers, with all its associated meanings in the eyes of multiple observers, and bearers, sometimes in the latter because of the former’s projected evaluations, even the reflective sitter. The word ‘blemish’ is such a negative evaluation, of which I give an irrelevant but telling illustration in a note below.[5]

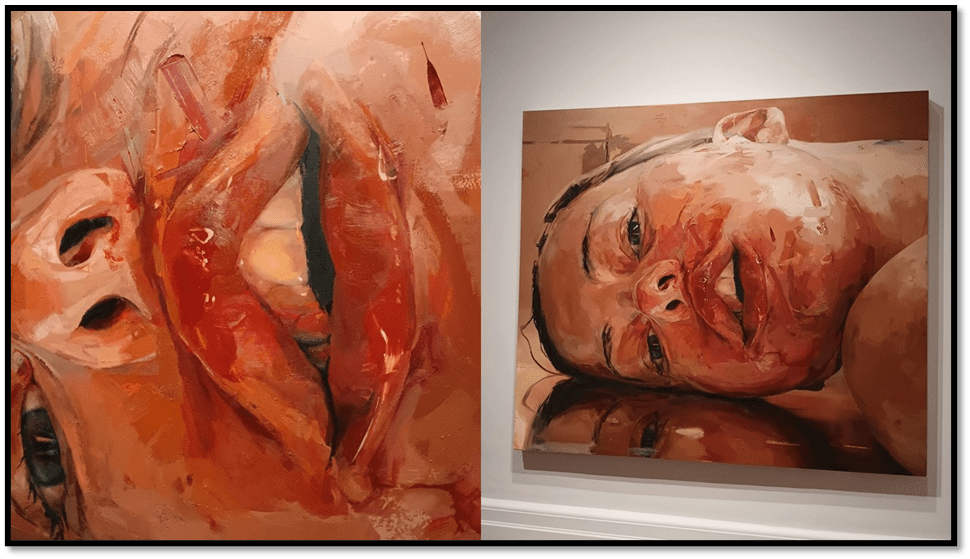

The piece above is called Interfacing (from 1992).

The direction of the sitter’s gaze almost follows a line parallel to a mole or wart on her lower cheek and a scar that leads from it, imperfectly rhymed with the direction of the eyebrow. Other marks may indicate the stress from internal body structure or abrasions on the skin. The nose is perhaps structured more flatly because of the damage from an accident or facial trauma inflicted by another or herself. As I write back I note how I assume femininity in the sitter but can that be justified, though the nails on the fingers that push overmuch into the cheek seem to have nail polish – but how indicative is that.

The nearer I approached the method of painting that wart, the more interested I became in the marks of paint that constituted as design on one level (that of painterly empathy) and illusion of reality on the other, including the sitter’s personal self-consciousness of being seen with this stigma.

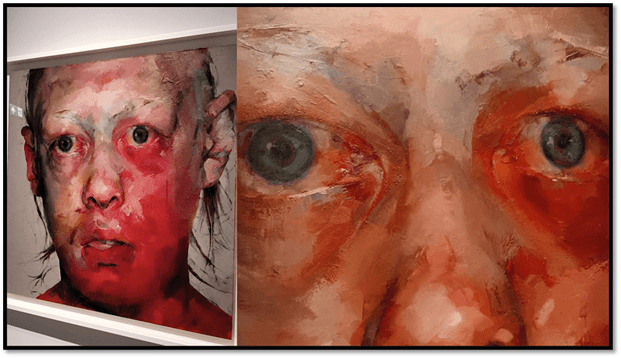

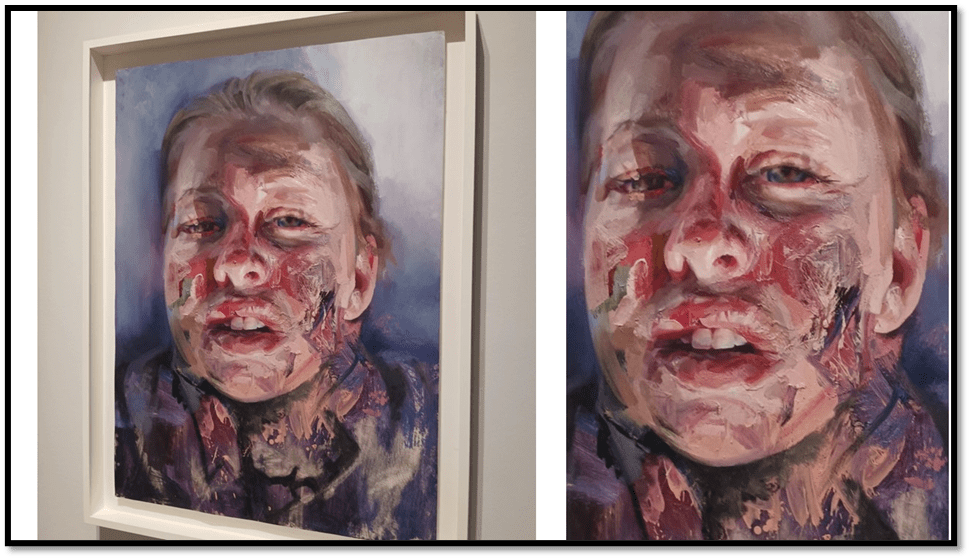

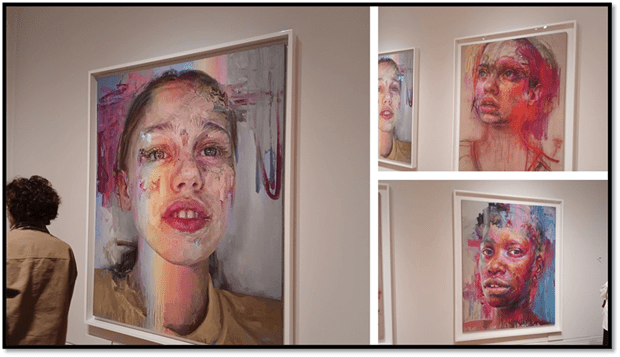

Marks on the body related to multiple life-stressors involved in their production also have a kind of relationship to their designed production in paint. Some are hard-to-explain naturall productions of diversity in internal body regulation, other are historical wounds and scars. Sometimes those life-stressors appear to take precedent, when the figure’s vulnerability is presumed. This can be done with what might be exclusively female figures, although the exclusivity is deeply uncertain, an issue we are told in the catalogue was derived from Saville’s reflection on female experience and its representations from the study of the feminist deep thinker, Luce Irigaray, who she quotes – in text in ‘mirror-reversal, over the surface of Propped. But, be that as it may, I think what Andrea Karnes says in her catalogue essay on the deep influences of Willem de Kooning as a painting practitioner very telling other method as requiring that sex/gender is often difficult to read, working – like the Stare heads Karnes is discussing – from models that are not an ‘archetype of womanhood’ as in De Kooning but that of a ‘specific individual’ where sex/gender markers can be – and very often are unaided by artifice – non-binary in terms of sex/gender. Individuals favoured by Saville, Karnes says are boundary being – sharing both traits of the modern ‘normal’ and the pathological (or evidential as in crime mugshots), life and death and querying ‘the constitution of femaleness itself’; The heads ‘may or may not be a woman: the figure is androgynous’.[6] In that light look at some pictures that often most disturb because they record the mark-making of past human violence in the studied marks of the artistic process.

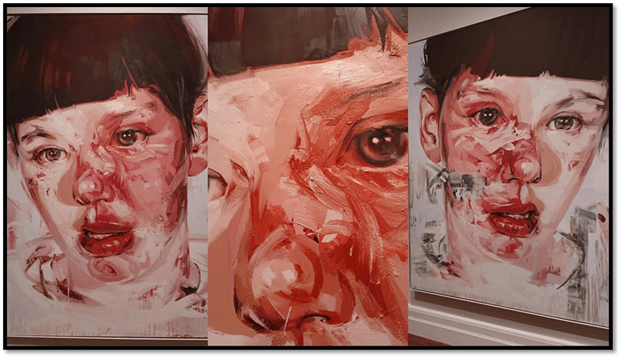

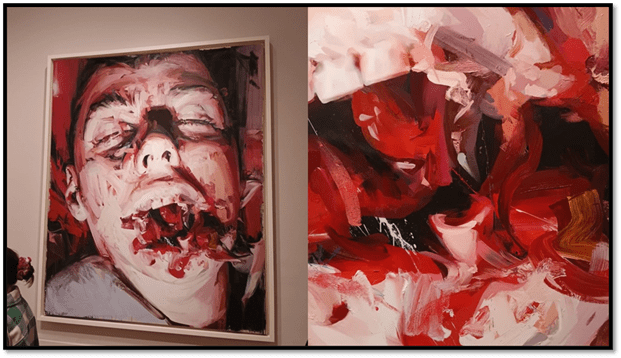

Left: Shadow Head (2007-13), Right: Bleach (2008)

Shadow Head is so ambiguous – their eyes alive, if, on the right stained by shadow, stain or bruising, in the near abstract forms used to refashion their pained right cheek and the abstract work below and around the neck offering the head, as if it were a forensic specimen severed at that place. Pain, pleasure, beauty and something non beautiful. Here is an example where the lips invite you not only to touch but kiss, and yet what ambivalence that creates in a viewer. Bleach is not less so – but is it called that to explain the vary-toning of the hair or the ‘damage’ on the face – the flattened nasal structure too not only being an ambiguous sex-marker but standing between nature and violence.. Yet for Saville, as must be the case, making these form details are also part of painting / sculptural process. She says to Sarah Howgate:

I like the structure at the sides of noses and often find ways to swing paint around it to the eyeball, which hopefully gives a dynamism and internal movement right in the middle of the head.[7]

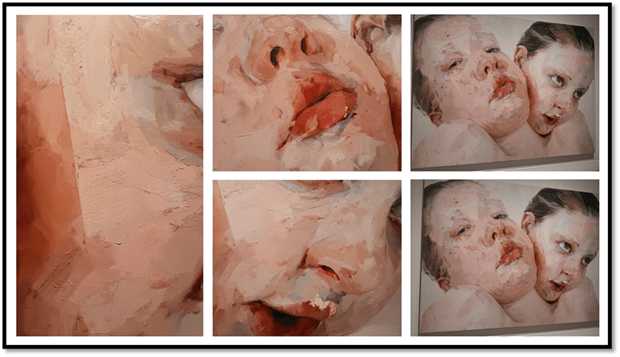

Lips can be made appealing but as if by the effects of violence too. Disturbing isn’t it? It is as if, eventually Saville seemed to prefer to make the marks identifying sex/gender less important than the vulnerability itself, and her sitters take the look of children – figures that may BE children or look child-like. These figures allow for the imagination of the heinous possible causes of marks that can look like shed blood, broken facial features, wounds and scars

The less the verisimilitude, the more the sense of invention in the markings of paint from the point of view of its abstract design, but the more the sense of an originative violence that calls out empathy and tender feelings for someone whose experience of these ambivalently mixes them up as carriers of human intention towards them, as, of course, in the Red Stare Heads (2007-11).

Sometimes the effect is very subtle indeed, the marks more difficult to interpret if not the appeal of vulnerability and expression of some kind of need to the viewer, which isn’t aimed only at an effect of appearing sincere or authentic but is a place where art and artifice meet in the construction of the image and stereotype of childhood, even as performed sometimes by children learning to use their assets of seeking attention and care – and getting often its direct violent abusive opposite.

But look too in the above (details of Hyphen (1999) at the nature of the sexualisation of those images – its effects in adult violence that has left marks and the radical nature of the overt technique cutting into the picture by the artist displaying her skills. Sometimes the violence itself seems the source of a kind of infantilization, either an adult terrified back to childhood trauma, or the child’s awareness of the failure of its appeal to power that have made it marked and still vulnerable. Some of that is related to the ungendering / unsexing of the figure. There is even a kind of violence in entitling the example below Figure II. 23 (1996-7):

At these times the horror that might get evoked from the image is deflected into the interest in aesthetic marking and design creation – How are these marks made, suddenly becomes a pronged question. It is one it OUGHT to be difficult to ask yourself!

When an adult might be being rendered transparent to the power of the seer being exerted over them – brilliantly conveyed by the reflective mirror (or mortuary slab) in Reverse (2002-3). There is an invitation in residing in this picture but who housed it there. The red of the lips marks violence and evokes passion.

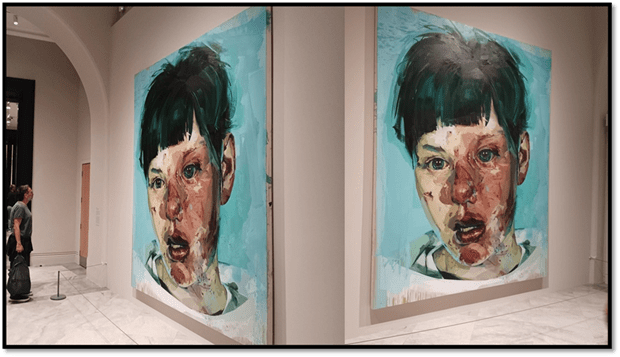

In such situations, at one level the consequences of marks upon the body become one akin to forensic, the ‘victim’ being uncertainly living and perhaps dead. And more shockingly, the effects of violence become prompts to a kind of appeal, that disturbs the viewer. Although in both cases the pull is defended at the level of technique where in the brilliant (and huge – see the departing gallery viewer by its side) Witness (2009), the face is pulled apart – in death or a record from the life – by the painting falling into abstraction. Indeed often, in building these heads, Saville says she starts from decisively being able ‘to drive bright green or yellow oil bar right through the structure of a head, and build the flesh around that’.[8] In witness the violence is not of driving a bar into the head but from excavating red from the figure’s interior through cutting up an orifice. The paint literally screams beautifully.

In some paintings, the death / life ambivalence is even open-eyed, but to such an effect that is disturbingly aesthetically at total odds to the norms of comforting appearance, as in the 2005-6 Rosetta II. There the eyes are made anti-mimetic and symbolic of the difficulty of reading this particular Rosetta Stone or indicate a past violence that has been supplemented by new marks and possible cuts, erasures or stains from effluents thrown at the figure. Note the red stain, almost triangular, at the exposed neck, under the chin, but at that passage denying it the mimetic depth it need to merely copy reality.

Strangely, I find the 2005 Rosetta Study for this painting (right in the collage below) emphasising a stillness missing in the painting which has the feel of a revived corpse. Its stillness can be seen the more in seeing how Saville uses shadow drawing variations to give dynamism to living figures (however shut their eyes) as in (on the left below).

We will return to effects that Saville creates by drawing over her figures – I like to call it overdrawing or overwriting a little later. These effects are hard to classify as poetic or imitative – even the uses of slashing, or staining to derive the figures. The self-portrait below was new to me, but it plays with claims of autobiography that pull us in expecting a story to explain the overt marks on Saville’s face, without being able to discount the fact that they may be only part of the anatomising of her painting process. It is called Self-Portrait (after Rembrandt) (2019)as if to emphasise that its methods are based on long study of processes as a self-portrait maker in the great artist, rather than an expression of personal done harm to her body by some agent, or a symbol of psychological traumatic scar. It should rank as one of the great self-portraits, owing something to Bacon but somehow beating Bacon at his own game.

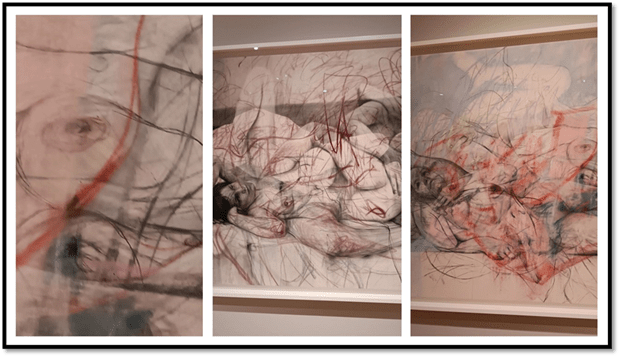

To embed the exploration of mark-making in flesh – at skin-surface level and deeper is, I think an extension of other interests in the way the body attracts and wears marks made on it and, of which it is constituted (sometimes by discursive texts), for the artist in landscape geographical or semantic terms. Look again at Propped and the overwritten Luce Irigaray text, unreadable without a mirror, and the way the mounds of flesh are drawn over by intrusive contour lines in Plan (1993). In the latter, the effect is of a notional violence to the woman’s body – transforming it into the landscape owned by another – but it has some relationship to how a painter distributes paint to create illusions of varied mass and volume in nude painting.

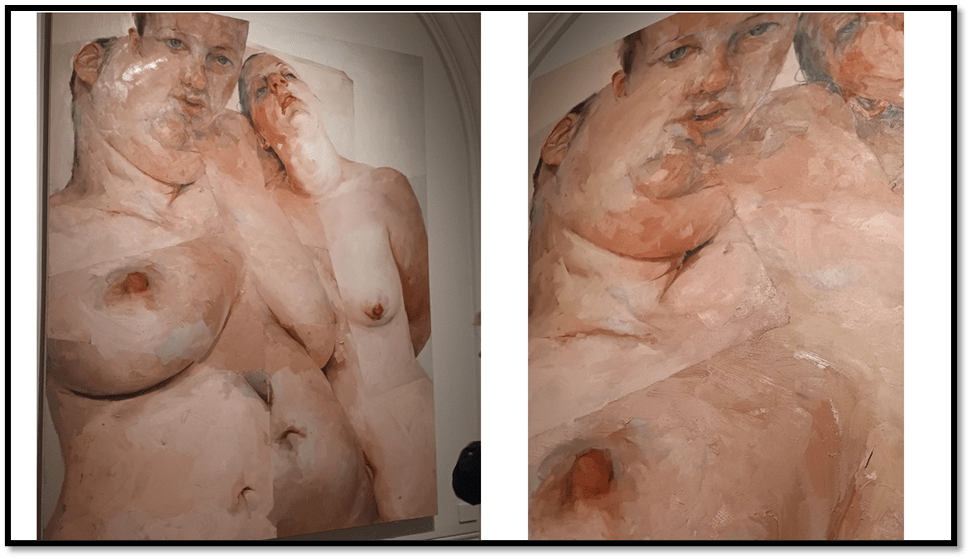

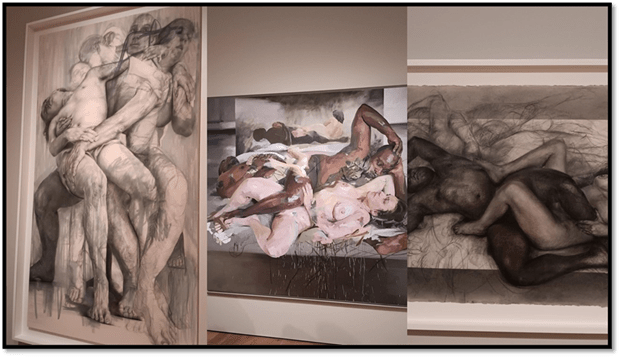

Take that further and the painter can vary mark-making to change what some call ‘natural’ boundaries to the body. Such margins are no longer considered sacred – the discourse of surgery being ubiquitous, as the discourse of body reconfiguration. Indeed body margins have never needed to be considered sacred – body art in some cultures is about sharing the skin often within a group or community. Margins have long been considered malleable by skin marking both penetrative and not (make up and costume for instance) but which blur fact and fiction in the relation of self to an authentic original term. Without evoking the surgery sometimes chosen by some trans people, Saville has mixed up sex/gender markers by blending figures so that the origin of each is not individuated but shared, either as visual illusion or allusion to commonalities of body as well as singular differences in some biological sex markers, as in Ruben’s Flap 1998-9).

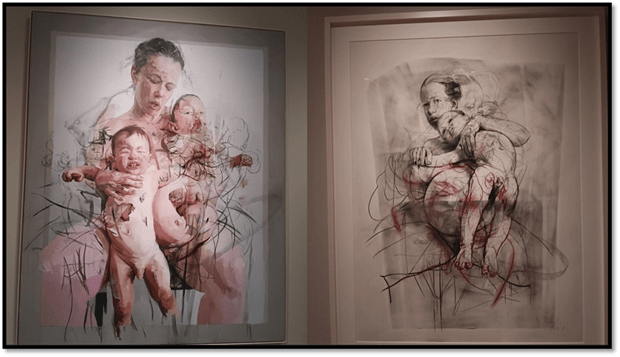

In her interview, Saville suggests that she cannibalised her experience of pregnancy and childbirth to make sense of her painting biography too, even developing it more into the use of drawing methodologies will require less preparation and clearing up than painting with oils:

Spending most of your life painting flesh and then growing a body inside my body was a profound experience. Giving birth was beautiful and primal. I continued painting after my children were born at the times they were sleeping, …[9]

In fact drawing and painting are used to overwrite the sense of the fusion of body boundaries Saville experienced in childbirth – her over-drawings of oil often leaving a chaotic commentary over images mixed up of struggle and less achieved moments of peace, something she sought to turn to art by looking to, and critically unpacking in visual ways, classic mother-and-child imagery in Renaissance art:

Renaissance sculptural and painted groups also speak from under her work with a sexualised adult content – her interest in the interaction of bodies often being in the way sex markers get as indistinct as gendered ones, so that these great paintings (which I choose not to dig deeply into can neither be called heteronormative nor as concerned about other body marker distinctions like race, class and differing embodiments.

One can stare forever at the great painting Compass (2013) and not discover how sex markers combine nor test their validity and reliability as individuations of single bodies of a certain skin colour, sex/gender or ‘wholeness’. Where is the flaccid penis at the focal centre of the picture derived into a whole figure. Is the (apparently male) brown hand that of the figure with facial male sex-markers but with defined breast shaping on a thin body.

At other times Saville has over-drawn sexualised masses and volumes to the effect of creating dynamism but a certain feel of the transgressive, especially when the drawing appears to be red conté pencil or pastel.

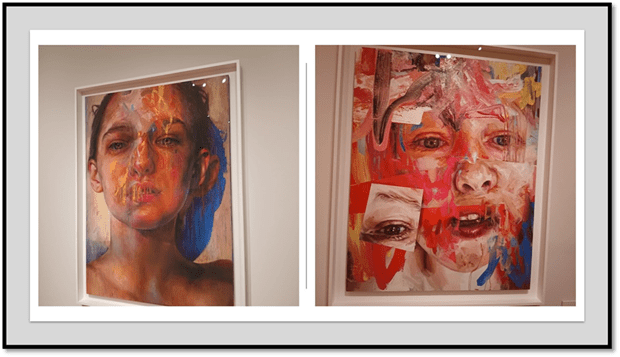

But let’s not delay too long those paintings which mark a new development for me in Saville’s work and a welcome one, which Emmanuele Coccia in the catalogue calls her invention of ‘The Rainbow of Flesh’, and summarises in the gnomic statement: ‘To paint means to look for and to find the rainbow – the explosion of the colour palette – in the flesh of all things’.[10] But, of course, like all big and beautiful plangent statements it is not the whole story and has a history in the past work

Those heads are still severed, colour marks past experience of differing significance and range of meaning to the person or us. The heads can float like the severed one of Orpheus in the artist’s songs of colour but they still dissect the head back into what constitutes it – as human or art object. It still streams – with tears or blood but is more intensely pleasurable because of its colore painterliness, in the language of academic art. And much is done with technique that has signification in other registers of discourse – erasure, inversion, fragmentation and partializing for instance.

And though I wanted the rainbowed angel in Messenger (2020-1) to be a queer angel allied with the colours of our rainbow, I think it is silly to ask to limit its diffusion in this way, for even unlimited it still defies the norms that constrict all of us and need not do so in a world built for diversity and equality in community. These paintings are beautiful beyond words and, I think, beyond the pain of some of the earlier work.

And they make us joyful in our sharing of Saville’s painterly absorption in some passages of great beauty and sadness. The boldness of the brush strokes, the refusal not to blend abstract and realist methodologies – it is all on message.

When you look at her naked children in her new family drawings you see the impetus for Compass. This is people refusing to find their naked bodies ‘dirty’ or ‘naughty’.

And, after all, we need painters to show us by looking at past methodologies – below Michelangelo on the left, Francis Bacon on the right – to see that figurative art has always embraced the abstract.

In the passage through the gallery, this is one exhibition where I did not crowds as onerous as in past exhibitions – I think Saville creates both reflection and openness in the same way as she invites us to her art without hubris at the amazing in her methods. We just share them.

And those passages of paint. They are sublime. Do see this wonderful exhibition. It would be a deep regret not to for me.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Jenny Saville & Sarah Howgate in conversation (2025: 36) ‘The Hard-Won image’ in Laura Cherry, David Frankel & Rosalind Furness (Eds.) Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting London, National portrait Gallery Publications.33 – 64.

[2] Ibid: 36

[3] Ibid: 41

[4] John Elderfield (2025: 17f.) ‘The Anatomy of a Painting’ in Laura Cherry, David Frankel & Rosalind Furness (Eds.) op.cit.16 – 31.

[5] It reminds me of the then Prince Charles in 1984 complaining that the new building on the National Gallery (the revered Sainsbury wing) was ‘a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend’. How self-referring and narcissistic, was the process of manifesting taste in the British aristocracy then! See it here – http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/8046449.stm

[6] Andrea Karnes (2025: 102f.) ‘On Jenny Saville and Willem de Kooning’ in Laura Cherry, David Frankel & Rosalind Furness (Eds.) op.cit.98 – 103.

[7] Jenny Saville & Sarah Howgate in conversation (2025) op.cit: 40

[8] Ibid: 36

[9] Ibid: 41

[10] Emmanuele Coccia (2025: 144) ‘The Rainbow of Flesh’, in Laura Cherry, David Frankel & Rosalind Furness (Eds.) op.cit.142 – 144