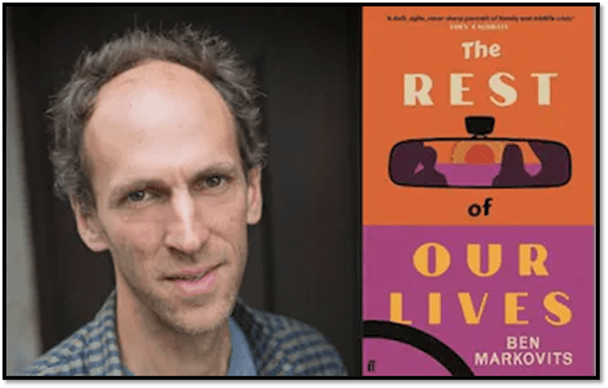

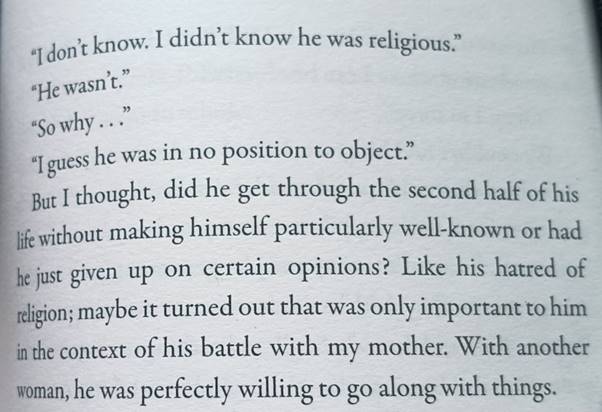

Thinking of his father, John Layward, who has ‘He is gone into the world of light,’ inscribed on his flat grave, the protagonist and narrator, Tom Layward, of Ben Markovits’ Booker-longlisted novel wonders whether that proud man’s ‘hatred of religion’ ‘was only important to him in the context of the battle with my mother’. So what did he do with the ‘rest of his life’ with another wife entirely?. This thought may consume him – namely that life is defined around battles and that once he does not ‘want to fight these fights anymore’ he needs ‘to think of something else to do with the rest of my life’[1] This is a blog on Ben Markovits (2025) The Rest Our Lives London, Faber.

Yesterday I was far from ready to try to respond to this novel, which I believe to be magnificent. Nevertheless the point of my Booker longlist blogs is merely to start the process of thought on them, not to conclude it. Though much in the novel speaks to me, after reading it, I decided that it refers indirectly to a poem that must haunt Markovits, Henry Vaughan‘s They Are all Gone Into World of Light. Indeed as I puzzled about this, I wrote a blog on it (see this link) to get me prepared to look more widely at his new novel, the first for me, The Rest of Our Lives. In that blog, I say this – I might as well quote myself directly:

Strangely enough the novel references the poem but not through the consciousness of its narrators or the characters who play a part in the novel. But one reason I can’t move on with my blog is that I need to see why Markovits may invoke the Vaughan poem so indirectly as I shall below show that he does. Vaughan was a Catholic, as is the main character, Tom Layward – though the book is largely about lapsed ethno-cultural and social identities (Jewish ones largely because Tom’s wife Amy is from a notable and significant Jewish family – the Naftali family) – and their sequelae in post-religious cultures.

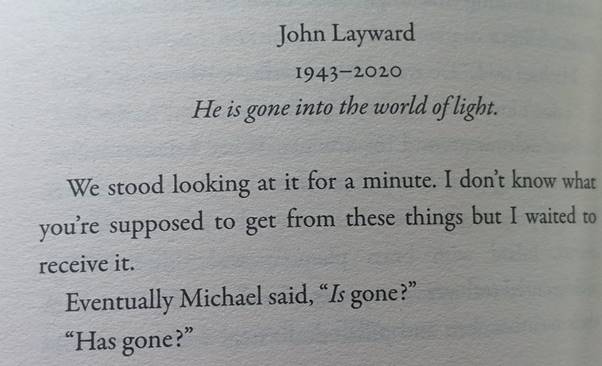

Nevertheless, Tom’s mother’s family, and that presumably of his second wife, is Catholic, and Tom wonders how his father must have finally become ‘perfectly willing to go along with things’. The thoughts arise because of the inscription on his father’s grave, which – though the family must have known it be be by Henry Vaughan, Tom and his own son, Michael, do not, they only know the sentiment of the inscription must be ‘religious’ – Catholic of course. Markovits makes that clear by an exchange around the grave, which I will add photographically because the layout of text seems important: [1]

The casual debate over the tense of the verb in the inscription (‘is gone’ which the men think should be ‘has gone’) is to show to anyone who does recognise the source of this adapted form inscription, as the family who had it put there certainly did, that the characters did not. Of course, it also shows they ‘know’ that the dead are not factors in the present world of action. Vaughan is a prized poet of Catholic communities – the one ‘loyal’ seventeenth century ‘Metaphysical’ poet (one trained in the courtly ways of the learned ‘wit’ of the court and capable of cross-referencing many systems of knowledge and belief – excepting the more Baroque Crashaw) of that Baroque Age. For me, I know it matters to Markovits this reference but I have neither worked out why that is so, and how to use my troubled response to this moment in my write up of my responses as a whole to the novel. Hence, this blog takes my equally troubled existential response to ‘twilight’ (still a ‘heavy lighting-up time of the day’ for me) as its theme. Here is the poem in full:

They are all gone into the world of light!

And I alone sit ling’ring here;

Their very memory is fair and bright,

And my sad thoughts doth clear.

It glows and glitters in my cloudy breast,

Like stars upon some gloomy grove,

Or those faint beams in which this hill is drest,

After the sun’s remove.

I see them walking in an air of glory,

Whose light doth trample on my days:

My days, which are at best but dull and hoary,

Mere glimmering and decays.

O holy Hope! and high Humility,

High as the heavens above!

These are your walks, and you have show’d them me

To kindle my cold love.

Dear, beauteous Death! the jewel of the just,

Shining nowhere, but in the dark;

What mysteries do lie beyond thy dust

Could man outlook that mark!

He that hath found some fledg’d bird’s nest, may know

At first sight, if the bird be flown;

But what fair well or grove he sings in now,

That is to him unknown.

And yet as angels in some brighter dreams

Call to the soul, when man doth sleep:

So some strange thoughts transcend our wonted themes

And into glory peep.

If a star were confin’d into a tomb,

Her captive flames must needs burn there;

But when the hand that lock’d her up, gives room,

She’ll shine through all the sphere.

O Father of eternal life, and all

Created glories under thee!

Resume thy spirit from this world of thrall

Into true liberty.

Either disperse these mists, which blot and fill

My perspective still as they pass,

Or else remove me hence unto that hill,

Where I shall need no glass.Why a twilight poem? The poem is built upon the paradox of a man waiting in the uncertainty that can be indicated by the twilight …

In Vaughan, the dead he praises are in eternal light he believes. He, like Andrea, sits ‘ling’ring here’ (on earth – dying, as are we all, but not yet dead) in a world with very little joy, as he sees it. And there is the ‘twilight piece’ in this much earlier poem – an evening betokening doubt of what is to come next – condemned to the ‘rest of our lives’ before ‘eternal life’ and eternal light (he hopes):

It glows and glitters in my cloudy breast,

Like stars upon some gloomy grove,

Or those faint beams in which this hill is drest,

After the sun’s remove.The only light on earth is the partial light of distant stars or faint beams from a descended sun. Of course there is a homophonic ‘pun’ here (to be expected of seventeenth century gentlemanly educated ‘wit’ (in its seventeenth century sense of the use of quick thinking in the association of things by metaphor) of ‘sun’ with ‘son’ (as in the Son of Man’, the name of Christ, the son of God). After all, the latter’s ‘remove’ could also be a source of dejection, were you not sure he would rise gain in a second coming, and you with him.

The whole conception of the poem is that man does not see things right, as God does – there is a famous reference at the end of the poem to what we call a ‘Claude Glass‘ (a mirror used by painters to understand the perspective to be achieved in creating a landscape drawing or painting, and to achieve that by toning down its colours in the gradations of twilight). God sees directly with the right perspective and in natural light.

Either disperse these mists, which blot and fill

My perspective still as they pass,

Or else remove me hence unto that hill,

Where I shall need no glass.Such a clever ‘witty’ metaphor that, using up-to-date (for Vaughan) human technology to show the benightedness of even hubristic modern human vision and ‘perspective’, which could be name of any optical instrument in the seventeenth-century – telescope or microscope. We can be removed too into eternity and we will need no glass then, for only now ‘do we see through a glass darkly but then face to face’ as 1 Corinthians 13 has it in the King James version.

But why is this a matter for Markovits’ John and Tom Layward? I think it is because the novel is posited on a fully accepted post-religious vision that does not look to notions of eternal life but only to what we have done with our lives thus far and our chances of doing something different (or the same thing differently – like ‘going home’ and understanding it anew) in the ‘rest of our lives’.

We were due an intelligent novel about existential mortality, and, believe me, this is it. But you will see why I might not write it quickly. There is life beyond battle – the great sadness of this novel and its triumph is that it deals so strongly with the dilemma of the ‘angry white male’ [2] and tries to understand that perspective beyond racism, sexism and the heteronormative. That is a risky business. It might yet be seen as giving in to these very forces but I don’t personally think it is. In a very real way the commonality of death might yet save us from perpetual battle – for it betokens a day in which diversity is part of our communality. After religion, communality is our only hope – especially in a world that keeps opting for hopeless white angry male anger, or its equivalent of collusion with it, across all differences.[2]

Notes to extract:

[1] Ben Markovits (2025: 198f.) The Rest Our Lives London, Faber.

[2] ibid: 16, 151 to pick out but two examples

[3] Cited Christopher R. Miller in summary of ‘Keats and the “Luxury of Twilight”‘, see it at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/invention-of-evening/keats-and-the-luxury-of-twilight/F7F8B592D3E09961162CAD2F37CD187B

The rest of this blog is likely, if my broad guesses at the end of that blog hold any water, to expand on the last two paragraphs above, I have outlined in these that I believe the phrase The Rest of Our Lives to be a highly meaningful title for a novel about contemporary existential mortality, and marked as such in the novel, and we might first go to the highly significant scene where John, finding himself on a road trip that he has barely planned consciously, but is an extension of the last flight from his nest – that of his daughter Miriam (or Miri) being taken to university as the beginning of her independent life, revisits the other landmarks of his past – his college friends, including the ‘pick-up basketball players with which he is associated, his first girlfriend, his son, and the last remnant of his father – that gravestone at the cemetery at Newport Beach – to mention only the most prominent). It is a kind of voyage into his own past – to see what his life was like in the light of facing the ‘rest of it’ after the turning point of Miri’s departure. It is a turning point especially because this is the event he has always intended to prompt a likely end of his relationship with his wife, Amy – broken and devalued for him after her affair with a Jewish friend of their Jewish family, the rather unctuous Zach Zirsky.

If anything I think that I have already said why this is a turning point for it posits a belief system where the once-living have ‘all gone into a world of light’ provided for them – theoretically speaking – by the God posited by their specific religion, here the God of Christianity. Yet nowhere along this road trip does Tom get to identify what will happen to the ‘rest of his life’ as he posits in in this graveyard, except when he is given a set of outcomes of his prognosis, all of which project the ‘rest of his life in different possible estimated durations. We are never told which prognostic duration the doctors feel likely from their tests, which we do see happening, and which already for Tom are an outline of oncoming death. For instance, he is sent for a CT scan:

… into another room, where the scanner was one of those coffin-shaped capsules with a long tongue of bed reaching into the deep plastic mouth.[3]

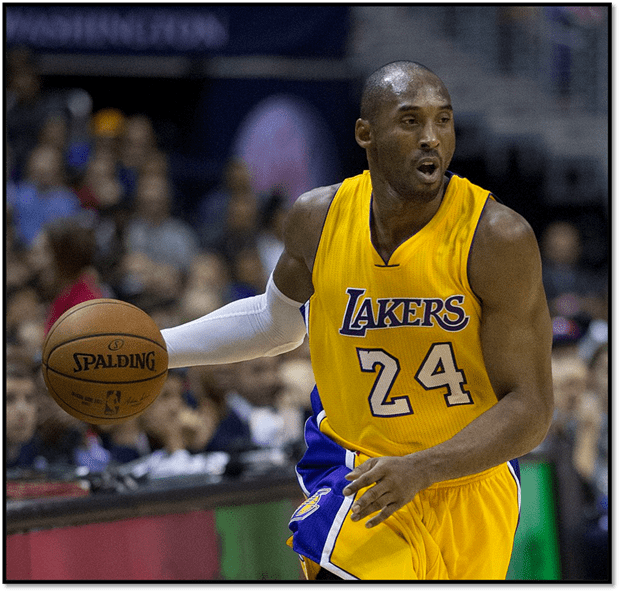

The ‘coffin-shaped’ descriptor perhaps ought to be a charged one, but here reads as almost clinical like the ongoing description of the room (‘Everything looked very expensive; everything looked very clean’), This clinical aspect of character is not unlike Tom throughout. At one point, but not only once, Amy says of his reaction, which is entirely about factual detail regarding the exact ages of people she is talking about, to her attempt to reach back into her past for an explanation of her time with Zirsky: ‘God, you’re cold’.[4] In other places there are moments when both other characters, and us as readers, have to read Tom as lacking emotion, or apparent emotion. And all of that matters once Tom has taken his son to see their dead grandfather’s grave and wondered just when he might receive some affect upon him. They wander off to see the grave of Kobe Bryant, the Black Catholic basketball player charged with a sedx-crime, don’t find that grave and notice mainly that everything is ‘so clean and so well-tended’.

Bryant playing for Lakers at Wizards 12/3/14: Photograph: Keith Allison – Flickr: Kobe Bryant CC BY-SA 2.0

But the event allows Tom, who is we must remember a professional academic teaching law, and specifically ‘hate crime’ to recall and tell the story to Michael that the man he has just visited – a 23 year old white basket ballplayer, Todd Gimmell, with confirmed views that the sport is biased to Black players – wore an abusively racist T-Shirt with KOBE WAS A RAPIST on the front and PROVE ME WRONG on the back.[5] This necessarily, one might think, causes Michael to speculate on what his father will do with the rest of his life – though he does not know that Tom is already under suspicion as insufficiently on ball about race and gender issues at work and is likely to be soon forcibly retired:

He asked me if I planned on pursuing that particular line of interest, and I told him, no, that’s all over. I’m not going back to the law school either, I’m done with all that. I don’t want to fight those fights any more. I need to think of something else to do with the rest of my life.[6]

The issue of where Tom stands on hate crime is peculiarly suppressed in this novel. He uses offensive anti-trans terms himself, which even his daughter questions. It is Miriam who names her father “Angry white male”, when as her father says, ‘she thinks I’m trying to be controversial’.[7] He gets trouble from students but we aren’t told why, apart from Tom’s own belief that he is, in softer terms than Miri’s, he is a ‘middle-aged white man who likes to teach dead white men’.[8] His oldest friend, Brian Palmetto, is a racist, confirmed in the belief that positive discrimination in favour of Black players is killing his basketball career and that if ‘you’re a white kid in America, the hill is too big to climb’.[9] It is Brian who sends him to see Todd who wears the offensive T-shirt mentioned above, but is also thinks it is ‘Black guys on the team’ who are setting him up as a ‘gay Barbie’: ‘Because they think every good-looking white guy is gay,” and cites Nietzsche on why white people need to reclaim their ‘master morality’ and abandon ‘slave morality’ to Black people.[10]

Strangely those ideas about the narcissistic version of men does often in this novel, in my reading, raise up meanings that root queer behaviour in the homosocial homonormative, just as queer theory posits the case. But this is not my purpose here, although it accounts for Tom’s refusal to acknowledge Amy’s thoughts that Miriam may be ‘lesbian’.[11] It indeed seems to animate the semi-conscious choices Tom makes to visit attractive white men as well as old girlfriends and his overt over-compensating sense of being attractive to all women. But I think I need more time to think any argument on that out. It has somewhat to do with the idea of resurrecting a life in which his ‘dumb idea’ was that he would write ‘a book about pickup basketball’, an idea that Brian Palmetto ‘got excited about’, saying he preferred ‘to play where the brothers play’.[12] That’s homosocial but isn’t it also at least slightly and unconsciously homoerotic.

On his road trip, Tom often seems to be seeking a model of how to live the ‘rest of his life’ (are Brian and Todd candidates for helping him in this respect) When he visits the now married family of his first girlfriend (at university), Jill McGurk, in Paradise Palms, he posits that, as he lays down next to her by the pool in borrowed swimwear: “This is the life,” …[13]. The point is that it is so much better than the past tense ‘the life we lived’ described with Amy.[14] What differentiated life before from the ‘rest of our life’ would be that it would no longer be a battle – as it had been for his father with his mother – or for him with his academic life in the law. But Michael is, I think, right when his father misunderstands ‘how bad things have been – on race and gender – for a very long time’, though Tom feels he knows enough to merely patronise Michael for his youth in his reply: ‘I lived through more of it than you have’.[15] He still believes entitled personal relationships trump ‘power dynamics’, perhaps because the power dynamics have always been thus far, in favour of the white males, who are now becoming ‘angry’ like Brian and Gimmel, or coldly, apparently analytically, ‘cold’ like Tom – unti he is diagnosed with a terminal cancer.

Tom’s journey passes through ‘Death Valley’ (at times the use of these real names recalls Bunyan).[16] But his real test is in meeting up again with his failed actor, brother, Eric, the ‘momma’s boy’ whose ‘wild life as an actor in LA’ never quite lived up to that description and who seemed so incapable of being anything other than how their mother describes him to Tom.[17]

In the end Tom looks continually for an identity beyond ‘power dynamics’ and what he calls ‘battles’ or ‘fights’. Sometimes when he loves he is wise in his advice to others in ways he finds it, like all of us probably, to be wise to himself. He says to Amy when she wants to exert control over Miri about how she configures her appearance – with ‘nose studs’ and the like:

If you fight her on this stuff, which you can’t control anyway, then pretty soon all your interactions are fights.[18]

It is advice he only benefits from when he knows he is dying and the only thing he learns to want is to ‘go home’ with his wife, having moved beyond the blame and guilt otherwise so plentiful in the novel. Henry Vaughan might reach such wisdom through God and the alternative light shed out of the world of time and space. For Tom there is no such solution – neither for his father who still pretended to believe there was for sake of the mutual comfort he might have found with his second wife. Maybe that is the communitarian equivalent of the perspective of God in Vaughan.

This is a magnificent novel by a magnificent writer and I have no more than scratched the surface of even my first response here. Read it and with me, read it again, if it is as it should, on the shortlist.

Bye for now

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Ben Markovits (2025: 198f.) The Rest Our Lives London, Faber.

[2] My blog ‘Somehow twilight at evening draws us to favour it. Why? After all it promises us nothing but the night, unless we hope to make the next day the first of the ‘rest of our life’!’ in Steve_Bamlett_blog available at: https://livesteven.com/2025/08/18/somehow-twilight-at-evening-draws-us-to-favour-it-why-after-all-it-promises-us-nothing-but-the-night-unless-we-hope-to-make-the-next-day-the-first-of-the-rest-of-our-life/

[3] Ben Markovits, op.cit: 215

[4] Ibid: 79

[5] Ibid: 181

[6] Ibid: 200

[7] Ibid: 15f.

[8] Ibid: 73

[9] Ibid: 155

[10] Ibid: 184

[11] Ibid: 46

[12] Ibid: 148

[13] Ibid: 163

[14] Ibid: 90

[15] Ibid: 38

[16] Ibid: 179

[17] Ibid: 93

[18] Ibid: 23

4 thoughts on “This is a blog on Ben Markovits (2025) ‘The Rest Our Lives’ London, Faber.”