Somehow twilight at evening draws us to favour it. Why? After all it promises us nothing but the night, unless we hope to make the next day the first of the ‘rest of our life’!

When I was a student at University College London, I used to find myself walking through Russell Square to and from the Senate House Library. I don’t remember the rest of the ‘poem’ I invented but a phrase from a bit of it still stays with me. The whole is about the light effects of that part of the day, as natural light fades – and artificial light on streets and from cars take over. I called it the ‘heavy lighting up of the the day‘. No doubt this phrase is as full of student bathos as was the rest of the poem, and echoed T.S. Eliot merely because his old offices at Faber and Faber still overlooked the square. However, I am thinking of all this mainly because I have just started a blog on Ben Markovits’ novel The Rest of Our Lives and I am not anywhere near finishing it for the day’s blog (I will however link it here when, and if, it gets finished). Here, however, is my working title:

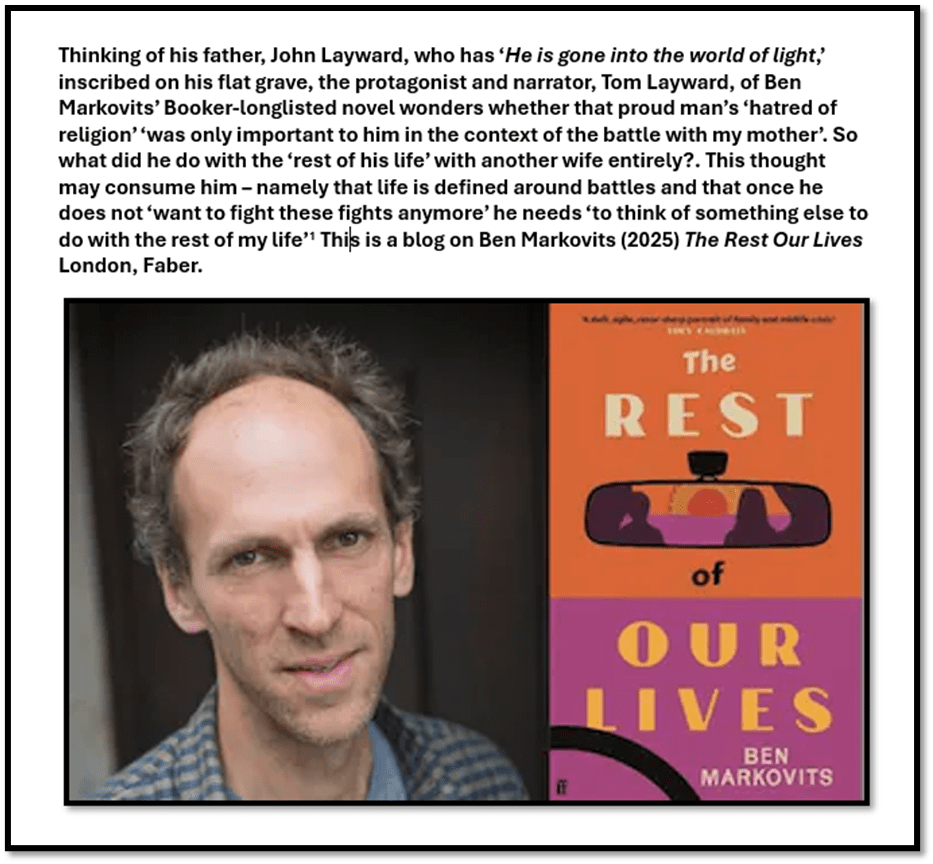

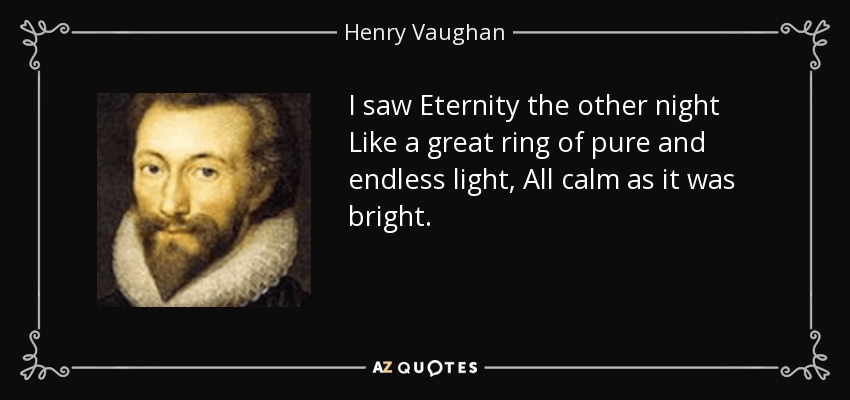

One issue in this novel is its clever use of reference to other writers. I offered you the working title of my blog because it refers to one such use – and to a poem that has always haunted me as much as it must have haunted Markovits, Henry Vaughan‘s They Are all Gone Into World of Light, a twilight poem that wishes it weren’t thus ( I will justify that comment later).

Strangely enough the novel references the poem but not through the consciousness of its narrators or the characters who play a part in the novel. But one reason I can’t move on with my blog is that I need to see why Markovits may invoke the Vaughan poem so indirectly as I shall below show that he does. Vaughan was a Catholic, as is the main character, Tom Layward – though the book is largely about lapsed ethno-cultural and social identities (Jewish ones largely because Tom’s wife Amy is from a notable and significant Jewish family – the Naftali family) – and their sequelae in post-religious cultures.

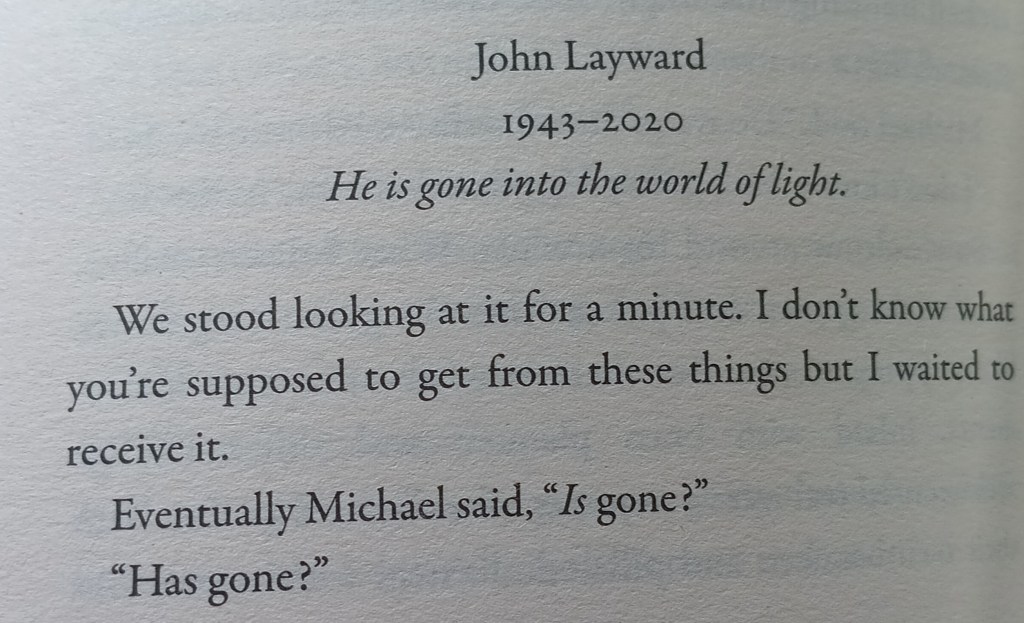

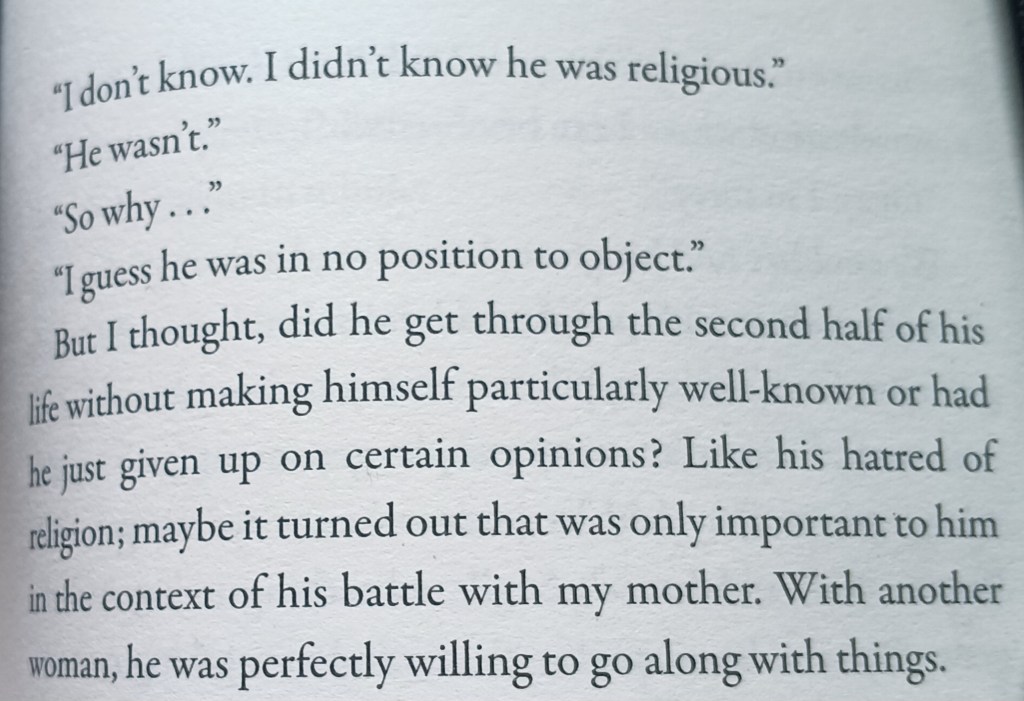

Nevertheless, Tom’s mother’s family, and that presumably of his second wife, is Catholic, and Tom wonders how his father must have finally become ‘perfectly willing to go along with things’. The thoughts arise because of the inscription on his father’s grave, which – though the family must have known it to be by Henry Vaughan, Tom and his own son, Michael, do not, they only know the sentiment of the inscription must be ‘religious’ – Catholic of course. Markovits makes that clear by an exchange around the grave, which I will add photographically because the layout of text seems important: [1]

The casual debate over the the tense of the verb in the inscription (‘is gone’ which the men think should be ‘has gone’) is to show to anyone who does recognise the source of this adapted form inscription, as the family who had it put there certainly did, that the characters here did not. Of course, it also shows they ‘know’ that the dead are not factors in the present world of action.

Vaughan is a prized poet of Catholic communities – the one ‘loyal’ seventeenth century ‘Metaphysical’ poet (one trained in the courtly ways of the learned ‘wit’ of the court and capable of cross-referencing many systems of knowledge and belief – excepting the more Baroque Crashaw) of that Baroque Age. For me, I know it matters to Markovits this reference but I have neither worked out why that is so, and how to use my troubled response to this moment in my write up of my responses as a whole to the novel. Hence, this blog takes my equally troubled existential response to ‘twilight’ (still a ‘heavy lighting-up time of the day’ for me) as its theme. Here is the poem in full:

They are all gone into the world of light!

And I alone sit ling’ring here;

Their very memory is fair and bright,

And my sad thoughts doth clear.

It glows and glitters in my cloudy breast,

Like stars upon some gloomy grove,

Or those faint beams in which this hill is drest,

After the sun’s remove.

I see them walking in an air of glory,

Whose light doth trample on my days:

My days, which are at best but dull and hoary,

Mere glimmering and decays.

O holy Hope! and high Humility,

High as the heavens above!

These are your walks, and you have show’d them me

To kindle my cold love.

Dear, beauteous Death! the jewel of the just,

Shining nowhere, but in the dark;

What mysteries do lie beyond thy dust

Could man outlook that mark!

He that hath found some fledg’d bird’s nest, may know

At first sight, if the bird be flown;

But what fair well or grove he sings in now,

That is to him unknown.

And yet as angels in some brighter dreams

Call to the soul, when man doth sleep:

So some strange thoughts transcend our wonted themes

And into glory peep.

If a star were confin’d into a tomb,

Her captive flames must needs burn there;

But when the hand that lock’d her up, gives room,

She’ll shine through all the sphere.

O Father of eternal life, and all

Created glories under thee!

Resume thy spirit from this world of thrall

Into true liberty.

Either disperse these mists, which blot and fill

My perspective still as they pass,

Or else remove me hence unto that hill,

Where I shall need no glass.

Why a twilight poem? The poem is built upon the paradox of a man waiting in the uncertainty that can be indicated by the twilight – it continued to be. In Robert Browning’s Andrea del Sarto, the artist sends his wife off into a twilight of adventure for her – possibly sexual adventure with a man she tells him is her ‘cousin’ – that is entirely lost to him, in his stolidness of sitting and waiting to achieve perfection in his painting if not in life, for both are summed up as a ‘twilight piece’, something dulled and hopeless, ‘toned down’ – full of the sense of ending rather than hope for a beginning, as imprisoned as are the ‘religious’ within their convent wall:

A common greyness silvers everything,—

All in a twilight, you and I alike

—You, at the point of your first pride in me

(That's gone you know),—but I, at every point;

My youth, my hope, my art, being all toned down

To yonder sober pleasant Fiesole.

There's the bell clinking from the chapel-top;

That length of convent-wall across the way

Holds the trees safer, huddled more inside;

The last monk leaves the garden; days decrease,

And autumn grows, autumn in everything.

Eh? the whole seems to fall into a shape

As if I saw alike my work and self

And all that I was born to be and do,

A twilight-piece.

In Vaughan, the dead he praises are in eternal light he believes. He, like Andrea, sits ‘ling’ring here’ (on earth – dying, as are we all, but not yet dead) in a world with very little joy, as he sees it. And there is the ‘twilight piece’ in this much earlier poem – an evening betokening doubt of what is to come next – condemned to the ‘rest of our lives’ before ‘eternal life’ and eternal light (he hopes):

It glows and glitters in my cloudy breast,

Like stars upon some gloomy grove,

Or those faint beams in which this hill is drest,

After the sun’s remove.

The only light on earth is the partial light of distant stars or faint beams from a descended sun. Of course there is a homophonic ‘pun’ here (to be expected of seventeenth century gentlemanly educated ‘wit’ (in its seventeenth century sense of the use of quick thinking in the association of things by metaphor) of ‘sun’ with ‘son’ (as in the Son of Man’, the name of Christ, the son of God). After all, the latter’s ‘remove’ could also be a source of dejection, were you not sure he would rise gain in a second coming, and you with him.

The whole conception of the poem is that man does not see things right, as God does – there is a famous reference at the end of the poem to what we call a ‘Claude Glass‘ (a mirror used by painters to understand the perspective to be achieved in creating a landscape drawing or painting, and to achieve that by toning down its colours in the gradations of twilight). God sees directly with the right perspective and in natural light.

Either disperse these mists, which blot and fill

My perspective still as they pass,

Or else remove me hence unto that hill,

Where I shall need no glass.

Man Holding a Claude Glass by Thomas Gainsborough (as you see used in the eighteenth century – and after – too)

Such a clever ‘witty’ metaphor that, using up-to-date (for Vaughan) human technology to show the benightedness of even hubristic modern human vision and ‘perspective’, which could be name of any optical instrument in the seventeenth-century – telescope or microscope. We can be removed too into eternity and we will need no glass then, for only now ‘do we see through a glass darkly but then face to face’ as 1 Corinthians 13 has it in the King James version.

But why is this a matter for Markovits’ John and Tom Layward? I think it is because the novel is posited on a fully accepted post-religious vision that does not look to notions of eternal life but only to what we have done with our lives thus far and our chances of doing something different (or the same thing differently – like ‘going home’ and understanding it anew) in the ‘rest of our lives’.

We were due an intelligent novel about existential mortality, and, believe me, this is it. But you will see why I might not write it quickly. There is life beyond battle – the great sadness of this novel and its triumph is that it deals so strongly with the dilemma of the ‘angry white male’ [2] and tries to understand that perspective beyond racism, sexism and the heteronormative. That is a risky business. It might yet be seen as giving in to these very forces but I don’t personally think it is. In a very real way the commonality of death might yet save us from perpetual battle – for it betokens a day in which diversity is part of our communality. After religion, communality is our only hope – especially in a world that keeps opting for hopeless white angry male anger, or its equivalent of collusion with it, across all differences.

This is a magnificent novel. I will have a go at the blog again tonight, lest twilight leave me bereft in my favoured melancholic moment. Apparently Keats once said that all great poems have the effect of twilight: “the rise, the progress, the setting of the imagery should like the Sun come natural too [sic] him – shine over him and set soberly although in magnificence leaving him in the Luxury of twilight.” [3]

Bye for now

With love

Steven xxxxxx

____________________________

[1] Ben Markovits (2025: 198f.) The Rest Our Lives London, Faber.

[2] ibid: 16, 151 to pick out but two examples

[3] Cited Christopher R. Miller in summary of ‘Keats and the “Luxury of Twilight”‘, see it at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/invention-of-evening/keats-and-the-luxury-of-twilight/F7F8B592D3E09961162CAD2F37CD187B

One thought on “Somehow twilight at evening draws us to favour it. Why? After all it promises us nothing but the night, unless we hope to make the next day the first of the ‘rest of our life’!”