‘Edgar’s almost shrouded by the white swell of the fog. … All of Longferry – the tall spires of the churches and the chimney-tops of the terraces receding to the lights of other towns – has been snuffed out’. I think no other modern novel I know about has such a sense of being near to death, or having past beyond it in imagination, than Seascraper. Is that because the ambiguous character Edgar Acheson is correct to say that, when it comes to understanding the choices we either make, or seem forced to make, in life, “Art’s the only way … of making sense of it”. [1] This is a blog on Benjamin Wood (2025) Seascraper

I can’t imagine anyone not liking Seascraper for it is the most atmospheric of novels, despite the brash gloom of its atmosphere (for instance in the use of a term like ‘snuffed out’ to associate the loss of a town to the vision of an observer to a violent death) and of the inset depression and premature sense of advanced age of most of its characters. And it is more than depression that is evoked in the character Edgar Acheson, an American film director who continues to live as if he were still significant in that role whilst not being so. His mental fugue states and delusions of significance coincide with a vast appetite for a constant supply of a range of drugs: he describes himself in single words to increase the sense of uttermost loss of identity and sense of realistic future or consoling memory of the past: ‘Overwhelmed. Depressed. Despairing’. [2]

Its protagonist, Thomas Flett, is also depressed (but not so self-consciously) an though he is a very young man – just out of teenage – his body feels to be that of a self-neglecting elder, with pain from his ingrowing toenails and a body whose appearance and smell continually reminds him of decay: ‘it always takes him half an hour to get his body moving properly. He’s barely twenty years of age, but he goes shuffling down the hallway with all the spryness of a nursing-home resident’.[3] Only to others is he young – to his mother, for instance, whom we learn anyway to be only 36 years old, ‘although’ (as she says) ‘that’s younger than I feel’.[4] Edgar is eventually recognised as young by Edgar Acheson, though at first he sees in Thomas and his equipment something of the character the undertaker, Runyan (though everything is ‘older’ for Runyan he admits), from his mother’s book The Outermost, which he plans to provide the substance of a planned film. In that film he suggests that Thomas might play the non-speaking part of Runyan’s ‘young assistant’.[5] And Edgar tells this young man: ‘Don’t bother getting older’, for time and ageing has taught Edgar thinks taught Edgar nothing.[6] The latter’s mother takes up the conversation in a way, arguing that ageing in time does have an effect, but a largely negative one, as far as living a life that is ethically guided. When criticised by Thomas for not believing in her son Edgar’s value in life, the following transpires:

She’s looking downcast now. “Well, that’s a very easy thing to say when you’re so young. Life has a way of undermining all your principles, when you get older.”[7]

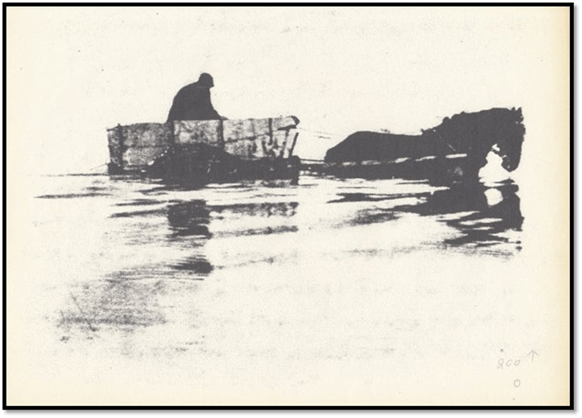

But it is not only that Thomas feels old. He is also committed to ‘old ways’, to the life of a ‘seascraper’ – unmechanised prawn net-fishing in the beach shallows, a shanker (or ‘cart-shanker’), that was the means of life of his grandfather, a life Thomas had to take over when his grandfather has a stroke and this becomes the only source of a dependable family income – his father being dead and never married to his mother.

Flookburgh cart shanker dragging for shrimps in Grange over Sands channel – in the 1920s (Keith Willacy collection) Available at: https://www.recordingmorecambebay.org.uk/content/catalogue_item/flookburgh-cart-shanker-dragging-for-shrimps-in-grange-over-sands-channel

Yet Thomas in his own day has no contemporary peers:

In his grandpa’s days, the shankers all rode out in procession: twelve carts clopping down the promenade, their horses making such a din it could be heard above the ring of church bells. All those fellas have retired or moved away, and some are in the ground at St. Columba’s graveyard. He’s the only shanker left in town who’s steadfast to the old ways. [8] (my italics)

It’s worth noting that the way this is expressed suggests that Thomas chose to remain working in the ‘old ways’ by not seeking to modernise the practice of the occupation as others must have tried. There is a kind of moral resistance to temptation suggested in that term ‘steadfast’. It is repeated with even more of that suggestion later, as he painted, almost allegorically, as the guardian of the values of the coast and its ancient means of ensuring the survival of human life:

The little snippet of the coastline he relies on for his livelihood does not belong to him or anybody, but it’s always there, preceding him, outlasting him for sure, and he can recognise his loyalty to the ghosts that walk along it – he can even manage to respect himself fo being steadfast to that work – but there’s no meaning anymore.[9]

The language of loyalty and faith is invoked and the value of resistance to the allure of a fast moving modernity but the tone is mixed with the elegiac – not quite gone, the work will not endure as does the coastline and already dead with respect of bearing significance or meaning. At another point, earlier than the latter, he thinks of the ‘motor rigs’ that have replaced the carts at Broughton – a place that seems to bound the imagination of Longferry inhabitants. Now he has, as he thinks, a hundred pounds from Edgar he could’ drive a rig and teach himself a different method’ of shrimping in deeper waters, and with others in a ‘fleet’: he can perhaps even reduce his working hours, and have time to court Joan Wyeth.[10] He doesn’t even know he tells Edgar soon after what ‘ties him to a shanker’s life’ – since the wage could be acquired in other ways and there is in that life-role choice ‘no sentimental gesture to the man who raised him’. He opts for an explanation that he is held there by ‘a kind of gravity’, as if by a force of natural physics.[11]

Even when in a kind of dream fugue he meets his dead father, Patrick Weir, who had no ties to fishing and was his mother’s History teacher, married elsewhere, and who died in the War, that father is singing songs in the role of another ‘waggoner’ (in fact it’s a song often hummed by Thomas we were told earlier) and that has no link to the facts of Patrick Weir’s life (though those facts were not shared with Thomas).[12] : ‘Who wouldn’t be for all the world a jolly waggoner?’ Of one thing we can be certain. Patrick would never have chose the life and Thomas knows that those that do are never ‘jolly’! When he learns a truer song from the dream-fugue father, it acknowledges that:

Lord, it’s a hard life, son, I know that it is, To rise with the tide in the morning at Longferry.[13]

And the old ways depend on a specific tide – an ebb-tide, where the sea retreats to an invisibility in the distance, in both fictional Longferry and, for example, the real sea vista from Heysham.

The novel opens with what it means to rely ‘upon the ebb-tide for a living’: it is a continual awaiting for a sea in retreat, aware that that’s the start of the sea’s tidal inflow will reverse the effects of time of its ebb to the point its wane: The opening passage is full of nearing ends – of a kind of starvation brought about by the scarcities of a later age in the old ways of shrimping:

Thomas Flett relies upon the ebb tide for a living, but he knows the end is near. One day soon, there’ll hardly be a morsel left for him to scrounge up from the beach that can’t be got by quicker means at half the price. Demand for what he catches is already on the wane, …[14].

And death, another ‘nearing end’, has a place everywhere in the novel – in the undertaker character Runyan from Edgar’s mother’s book who provides the model of what Edgar wants Thomas to be for him, for instance. It is also present in the threat of the sinkpits – area of quicksand in which men lose their lives, either by being ‘dragged below’ or drowned, whilst already half-buried, in the returning waters of the bay.[15] However, there is also the concentration in the novel of survival against the odds, and the deep depression that characterises both survivors and those who feel on the wane of losing the battle for survival. In the face of such endings men in the novel wonder about the value of what they leave behind them as a record, as Thomas does as he begins to drown in a sinkpit, until redeemed from death beyond dreaming by Edgar. Thomas at school is attracted to the force of Coleridge’s poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, by ‘its inherent sense of doom, its melancholy’, and ‘certain lines would surface in his mind like prayers when he was out at sea’.[16] It is prayers that keeps own ‘steadfast’, but it is also prayers that stop up the energy of moving on into one’s own future perhaps.

The effect of ageing and the onset of predictions of mortality seem associated for Thomas with the sea – though somewhat as we shall see redeemed from stasis by live music. Like Thomas there is in the sea a reserve of suppressed energy that it will refrain from mustering – just as Thomas refrains from courting Joan Wyeth until redeemed by Edgar, who himself must be a sacrifice to the ongoingness of live as it is possible for us to live it outside insanity. Take this fine description of ebb-tide seascape:

He wishes he could see the beach the way it must appear to Edgar, special and mysterious. But the parts of it which stoked his fascination as a boy – the strange withholding of the water, all the energy that you could sense but never see – have turned to ordinary components of his day.[17]

That image disturbs – the fascination with withheld reserves that is almost the fascination with the retentive power of the body, especially the bladder. It reminds us that his Grandfather or ‘Pop’ died of bladder cancer, as his mother tells Edgar and that the se is most emphasised as if sick because of the preponderance upon it of ‘bladderwrack’, a form of seaweed.

Pictures : Underwater – By W.carter – Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=81610786 & Single frond on beach – By User Stemonitis on en.wikipedia – Taken by Stemonitis, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1366410

The descriptions of bladderwrack associate it with the waste material of the body and with illness and death with its liquid filled vesicles, perhaps because the sea’s scents seem to infect the body by getting right inside its orifices in this book, as they do the ‘ripe’ smell of Thomas after his days of work:

The sharpness of the salt inside the nostrils, too. That festering scent of bladderwrack, which lies along the foreshore here like clumps of hair upon a barber’s floorboards. There’s a strange, spasmodic crunch each time the wheels pass over razor shells and gnarls of driftwood.[18]

The survival experienced by the shanker is a crude ofkind of self-sacrifice – which Pop sums up to Edgar as: ‘Providing is surviving … and what else should any man desire’.[19] It’s a life that stays open to opportunity perhaps, as if that other rich advice from Pop with its rich use of the idiom ‘stay alive’:

But Pop would often tell how you had to stay alive to opportunities in life, to never fail to notice when they tap you on the shoulder – …[20]

But some kinds of survival are unthinkable to Thomas and what Edgar provides him with is evidence that a man might survive, even though Edgar’s survival will turn out to be an effect of unearned not earned income – and from his mother. Not knowing the latter about Edgar he sense in him something well beyond his experience:

You could knock on every door in Longferry andnever find a man as interesting. He doesn’t know another soul who earns a living from his talents.[21]

That’s a kind of specialness Edgar fosters by his illusory life-stories and use of promissory notes on money he does not posses. He has even made himself into a symbol of hat looks like impossible survival:

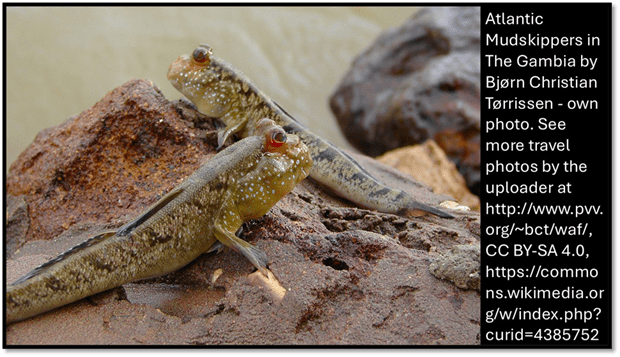

“… I’m like that funny fish who breathes on land, the – what’s it called? The mudskipper. That’s me. Somehow it stays alive despite the odds.”[22]

The mudskipper is, in all its variation a very ambivalent thing, but so is Edgar to Thomas, and it is Edgar, or the fantasy version of him he presents to Thomas at first, that allows him a chance of rebirth and resurrection into a new kind of life. The story of Runyan Edgar wants to film from his mother’s book , you will remember, is the story of an undertaker who has the power of ressurrecting the dead brought into his care.[23] Thomas is literally reborn out of the sand by being pulled from it by Edgar, and saved from a death accompanied by illusory memories of his biological father, Patrick Weir. Patrick invites him in a dream – fugue to join a band but Thomas’ mother later tells him Patrick was not all musical. The songs he hums are those Thomas hums of his own volition, the new song he sings actually invented by Thomas within the dream fugue.

It seems that Thomas makes good use of the point Edgar made to him, which I quote in my title:

“… That’s life, I’m telling you. Don’t bother getting older. Art’s the only way … of making sense of it”. [24]

And, as for making a living, will Thomas eventually buy a motor rig, spend less time on the coast, more with a wife already earning independently, Joan Wyeth at the Post Office, and begin to make a name for himself singing his own songs of seascraping life, starting at The Fishers’ Rest public house. It appears that this novel is a beautiful exploration of a kind of unlikely youth lived in the past, steadfast but without direction of motion other than following Pop’s chart to enable him to veer around sinkpits. The directionless is sometimes allegorised as here, where Thomas tries to navigate in blinding fog in murky water:

He rides in the direction he believes is right. The fog has gathered with a concentration that peturbs him, quickening his heart. The deeper they ride into it, the less he can discern – there’s just the rear end of the horse before him, carving through the eddies like the prow of some lost ship.[25]

Sometimes as here the prose (and it does it in its fine but troubling final sentences) loses direction where no direction seems right and the flight to survive seems to run into unforessen external threat. For I am troubled by the imagery here which suddenly sees the vanishing ‘rear end’ of an old horse, as onconcimg threatening front end of a powerful violent boat that cuts the water: for prows are not found at the rear of boats. The perturbance is deep and infects the careful reader only perhaps, but Thomas is such a reader. Another metaphor for this directionless is the loss of maps, charts or evidence of past motion read on the ground – such as the loss of footprints in the sand, perhaps the sign of a sinkpit.[26]

This novel might challenge some readers who dislike what used to be seen as vagueness in prose style in places – it takes risks in its prose – with mixed metaphor as seen above, to create further inner disturbance in the reader. It took time for me to reconcile myself for instance to the novel’s last lines, which some old Leavisite voice in my rear mind kept demanding was unrealised prose – without ‘objective correlative’ as Eliot called it. Let’s look at it here: it concerns Thomas fast rewinding a tape on a tape recoder (Krapp’s Last Tape comes to mind) – again about a kind of directionlessness or loss of gauging appropriate durations of travel (even in memory):

The mechanism whirs, the reels spin quickly – he’s not certain how far backwards he should go. His voice is bottled in the tape. It might have vanished by tomorrow. Time could wash it out before its heard again.[27]

Is this about a bottle washed out by the sea or the erasure of artistic marks. The prose wants us not to concern ourselves with this precision or, as I think, it does – and to show the mix in Thomas’ mind between old and new technologies and ways of computing and imaginatively manipulating time (again as in Beckett). And perhaps I feel that because this book so depends upon an artwork in its deep background – it’s the epigram of Mildred Ács book, from which she takes her first title choice from Rupert Brooke. The figure of Rupert Brooke haunts the novel, especially the lines cited in the epigram from his poem Day That I Have Loved (not named in the novel), used throughout, once Edgar draws them to Thomas’ attention, even as the final title of the novel about Runyan, Further Than Dreaming, which her son refers to as The Outermost. The poem goes (just to give the context in which the poet commits to the sea the body of a dead beloved (the lines cited as epigram are italicised) which dead beloved is an image of the ‘day I loved’ but which has disappeared:

Tenderly, day that I have loved, I close your eyes, And smooth your quiet brow, and fold your thin dead hands. The grey veils of the half-light deepen; colour dies. I bear you, a light burden, to the shrouded sands, Where lies your waiting boat, by wreaths of the sea's making Mist-garlanded, with all grey weeds of the water crowned. There you'll be laid, past fear of sleep or hope of waking; And over the unmoving sea, without a sound, Faint hands will row you outward, out beyond our sight, Us with stretched arms and empty eyes on the far-gleaming And marble sand. . . . Beyond the shifting cold twilight, Further than laughter goes, or tears, further than dreaming, There'll be no port, no dawn-lit islands! But the drear Waste darkening, and, at length, flame ultimate on the deep. Oh, the last fire -- and you, unkissed, unfriended there! Oh, the lone way's red ending, and we not there to weep!

I can see Leavis chuckling at this boyish post-Shelleyan mess of words, with its vague evocation of mystery in half-realised vague images like ‘grey veils of the half-light’. The whole is an image of the day ending – presumably a momentous day – perhaps his favoured man kissed Rupert. The poem is from the poems of 1905-1908, in Brooke’s ‘last year at Rugby, and his first two years at King’s College Cambridge, before he moved to Grantchester’. They evoke the image (actually merely a literary trope from the Eddas) of a Viking sea-burial by immolation, with touches of both Tennyson’s Morte d’Arthur and Matthew Arnold’s Balder Dead, though the narrative is thoroughly lyricised. Forgive me but I must quote from the relevant Matthew Arnold, necessarily an ideal to Rugby schoolboys like Brooke:

But through the dark they watched the burning ship

Still carried o'er the distant waters on,

Farther and farther, like an eye of fire.

And long, in the far dark, blazed Balder's pile;

But fainter, as the stars rose high, it flared;

The bodies were consumed, ash choked the pile.

And as, in a decaying winter-fire,

A charred log, falling, makes a shower of sparks,—

So with a shower of sparks the pile fell in,

Reddening the sea around; and all was dark.

For Thomas however the poem reminds him of the funeral of his ‘Pop’, the casket, and the ‘hopelessness that overwhelmed him and his ma. But it passed’.[28] He tells his mother that in reading her book he only got to Rupert Brooke but ‘I liked that plenty’.[29] He is the motif of his own resurrection in the phrase ‘further than dreaming’ that forms Ács novel title. He goes down into a sinkpit into a dream and further – in a fantasy trip and is reborn as Edgar pulls him out. It is seminal to the text that poem and its images speak too of Longferry beaches to Thomas. But it is a ‘morbid’ and ‘immature’ poem too surely, and it marks a place from which Thomas must grow, and let it ‘pass’. Whether it does is as sure as Thomas is in handling a tape recorder – we will never know if his overwhelming despair will or can return.

But I have meandered enough through this review. The novel is great I think.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Benjamin Wood (2025: 93 & 92 respectively) Seascraper London, Viking, Penguin Books

[2] Ibid: 92

[3] Ibid: 4

[4] Ibid: 68

[5] Ibid: 85

[6] Ibid: 92

[7] Ibid: 145

[8] Ibid: 9

[9] Ibid: 133

[10] Ibid: 84

[11] Ibid: 89

[12] Ibid: 68

[13] Ibid: 123

[14] Ibid: 3

[15] Ibid: 36

[16] Ibid: 34

[17] Ibid: 83

[18] Ibid: 82

[19] Ibid: 12

[20] Ibid: 31

[21] Ibid: 54

[22] Ibid: 24

[23] Ibid: 29

[24] Ibid 92

[25] Ibid: 96

[26] Ibid: 99

[27] Ibid: 163

[28] Ibid: 80

[29] Ibid; 137

One thought on “This is a blog on Benjamin Wood (2025) ‘Seascraper’.”