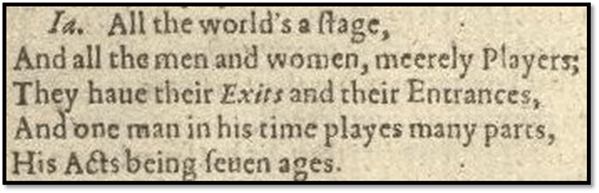

Is the idea that psychosocial or other roles are ‘parts’ played upon the stage a tired metaphor (from the too-often quoted lines of Shakespeare’s jester, Jacques, from As You Like It: ‘All the world’s a stage, …’). Why might modern novels then take up that idea again, other than to keep saying and showing the implications of psychosocial and aesthetic breakdown of those stagey illusions that life depends on? Or to put it another way: “Parts – a word that implied that there were parts and then there was a whole, into which those parts might cohere, a whole that might be … a body of work that could exist in the public imagination”.[1] This is a blog on Katie Kitamura (2025) Audition London, Vintage, Penguin Random House

The words immediately above (there as printed in the First Folio – see my blog on that on this link) are quoted so many times, often without knowledge of their source. Perhaps, in this case knowledge of the source may not help us, except in that this novel resolves (or more accurately ‘dissolves’) into the notion that an actor (who may be playing on the stage or an agent in any set of life events both has not only ‘many parts’ in sequence as in Jacques conceit (using both of the meanings set out in the linked Cambridge Dictionary) but ‘too many parts’ which ‘don’t endure, and once they are gone, their logic is impossible to regain’. Mostly, there is only the emptiness they leave behind’.[2] There is a fundamental difference between Jacques’ literary conceit that ‘ONE man’ has ‘MANY parts’ and the fundamental doubts in this novel of the enduring integrity (oneness or wholeness) of the many roles we play in life – whether we are an actor earning money from the stage and / or film or not.

This novel has a narrator (‘unreliable narrator’ as the literary critical jargon goes is an understatement – for reliability you need the defining qualities to sustain it of both coherence and integrity), who is also a character playing different roles (the most complex and questionable being that of a ‘mother’) and an actor whose many roles in many works of art – and sometimes in the same work of art as it is reproduced on stages at different times and places – which overwhelm any sense of integrity despite valiant efforts to appear to stop that occurring. Even the facts of the ‘parts’ she plays declare they are bogus – such as the part she plays in the invented film by an invented director, Murata, with an invented backstory. Murata, by the way, has many culture-specific meanings in Japanese culture:

In Japanese culture, kanji are characters that originated from Chinese script, and the meaning of a name changes depending on the kanji characters chosen. Even surnames with the same pronunciation can have different meanings based on the kanji used. Below are the kanji variations for “Murata,” listed in order of popularity based on household usage in Japan.[3]

Murata’s film Parts of Speech itself adds to the meanings of ‘parts’ in the book. That is because a ‘part of speech’ is the category that describes in linguistics the, in Wikipedia’s description, word classesor grammatical categories used in a language, and is, more fully:

a category of words (or, more generally, of lexical items) that have similar grammatical properties. Words that are assigned to the same part of speech generally display similar syntactic behavior (they play similar roles within the grammatical structure of sentences), sometimes similar morphological behavior in that they undergo inflection for similar properties and even similar semantic behavior.

Parts of speech in English from: https://www.scribbr.com/category/parts-of-speech/

And Parts of Speech, it can easily be seen are a way of codifying action, relationship and proximity. Often linguistic phrases play different parts, such as, for instance the crucial phrase ‘give up a child’, language used that was ‘confusing to say the least, that seemed to designed to obfuscate the reality of the procedure that I’d had’.[4] The confusion relates to interpretation of parts of speech, for the narrator realises that the status of the child as a ‘noun’ acts differently in relation to the verb and has an independence of it, if applied to either adoption or abortion procedure. That is to say that parts of speech matter in this novel, where some keen student will one day analyse its sentence structures in order to extend its resonance as a work of complex art.

The parts of speech also differ in aspects of meaning, subdivision or number for different languages, so much so that, as Wikipedia says: ‘variation in the number of categories and their identifying properties, analysis of parts of speech must be done for each individual language’. In this novel, written in English different languages are constantly invoked – for instance the narrating actress nots that for the film, Parts of Speech, she did not ‘speak the same language’ as Murata and thus she says that she ‘did my lines phonetically’.[5] We cannot know how deeply such linguistic play of reference and association goes in each episode of the novel.

But let’s take one very obvious instance where it matters. At one point the narrator interrupts her own narration of the young man Xavier asking her whether she had ever wanted children – that having grown out of the contingency of an earlier strange conversation -to say this:

People always talked about having children as an event, as a thing that took place, they forgot that not having children was also something that took place, that is to say it wasn’t a question of absence, a question of lack, it had its own presence in the world, it was its own event.[6]

It feels to me that what is being said here talks about the parts of speech. It takes a verb ‘have’ indicative of being a parent – ‘I have children’ and compares it with the negation of the verbal statement: ‘I have not any children’ and assesses them as nouns indicating an ‘event’. It does though not to force on us the cleverness of what is being done by the novelist here – after all, all events which have a name also indicate something that is, or has been, done: ‘I was born’ indicates the noun phrase – ‘a birth’ – but the novel is going to play a lot with why and in what variations ‘Not having a child’ is an event: relating to (issues discussed in the novel over a range of time, characters and retrospection or prospect: abortion, adoption, miscarriage. These all relate to states experienced by a woman either voluntarily, with some degree of choices, or as dictated by eventualities over which she has any control or can make choices. In discussing a ‘miscarriage’ (assumed not to have occurred in Part One) the whole degree of its meaning and significance to either of the two parents here concerned or to a woman especially in relation to the events that spoke of the state of her own body (here speaking of the moment of confirmation of pregnancy): …, it was a mystery to me how something so fleeting could be considered confirmed, when its meaning could dissolve, without warning, into absence’.[7] Paradoxically, whatever the narrator said in Part One, ‘not having a child’ becomes NOT an event in potential but merely the ‘absence’ she said earlier it was not. What strange things do distinction of the ‘parts of speech’ in English allow us to think.

That film name Parts of Speech is mentioned again in a different context later, but the name of the play directed and written respectively by the characters Anne and Max – who both play a number of other roles in relation to other characters – in which the narrator enacts a key role or ‘part’ is very often discussed in both Parts One and Two of the novel. The first Part deals with the play whilst it is in rehearsal and development, the second when at the end of a successful run. Without explanation given that play is referred to by different titles (and parts of speech) in each ‘Part’. Just near the end of Part One we are told Max’s play, directed by Anne is called The Opposite Shore. We are told by the narrator as an addition to her reporting indirectly Max’s summary of both the play and the character played by the narrator. The Opposite Shore implies a crossing or transition between one solid ground along a water course to another facing it (it is suggested it is from emotional closure and cold to what is open and warm, or in Max’s indirect reported speech to the narrator: ‘when your character achieves a kind of breakthrough, and reaches the opposite shore. … the moment where she locates her emotion, when the play breaks open, when she steps forward into life’.[8] Yet within 9 pages we are into Part 2 and retrospectively looking back at the play, as a success for writer, director but especially the narrator-actor, but that play is named three times in two pages as Rivers. Moreover the play is no longer about passage between binary states but about constant fluid transition ( the fact that is called Rivers, nor ‘River’ suggests the well-known phrase attributed to Heraclitus (but in the meme below over-expanded to spell out its nuance), which makes every single river plural, as it also does as every single person stepping into at different times: the lesson that “Everything flows” (Greek: πάντα ῥεῖ, panta rhei).

This too characterises the difference between Part One and Two, where characters no longer face only the challenge of transition between states, but into a second state that pluralises notions like self and ‘character’. The narrator reprises in memory her role in the play, Rivers:

Whereas a role tends to grow more solid and predictable over the course of the play’s run, in the case of Rivers there was such process of accumulation, the performance never seemed to settle, … / … countless paths seemed to unfurl before me, forking and then forking again, so that I was dazzled each time by the scene’s infinite contingency, the range of possibility laid out in front of me.[9]

How are we to deal with a novel that contains such deliberate breaches of its own integrity as a narrative – for these are but a few and probably the least noticeable. In Part One we are introduced to Xavier as a man of suspect motives and interest in the narrator who we later learn comes to see her to say: ‘I think you might be my mother’, a thing she tells him must be an impossibility because her only pregnancy ended in abortion.[10] Yet in Part Two he is and always has been her and Tomas’ son, whilst in Part Three he is a son whose every act distances him from her – in one his ‘likeness’ to her fades and in alliance with her husband both their faces become those of alien men who look entirely alike, their past selves ‘dissolved’.[11] This is so much the case that she can eventually say, as he keeps calling her Mom: ‘You’re no son of mine, I said, and he laughed. How could I be?’[12]

The roles of mother and son, in plays , novels and life can also be imitated and rendered ‘real’ – either in formal arrangements like adoption or in play where they hide other roles (some with problematic status in cultures where the biological family is considered safe from profane behaviours, thoughts and feelings. Yet Anne, who eventually employs Xavier also likes to both sexually flirt with him, be possessive of his attention and make him model a son to her being a mother, even saying she saw him as an ‘archetypal son’: leading to this strange two sentences from the narrator:

Xavier gave good son. He loved the part of it, he longed for the role, that was why he had contacted me in the first place.

The role of ‘longing’ and desire in relation to roles like mother and so sometimes muddies these roles. The narrator, at the end of Part One looks at Xavier and feels ‘a starburst of longing’. Longing for what. Within pages he will have become metamorphosed into her son. In Part Two the narrator is so in love with the potential released by her acting that she ‘longed for it in a way that almost carnal’.[13] This ‘carnal’ desire is not for Xavier but sometimes it seems to be, such as when she expresses jealousy of Anne who can possess Xavier as employer, senior director of plays and as a kind of lover, ‘something else as well’. She tries to resolve that by imagining both herself AND Anne as Xavier’s mother (‘Anne on the one hand, and me on the other, Xavier’s mother’. The descriptor ‘Xavier’s mother’ exploits the syntactical ambiguity in that sentence, yet the narrator can also reclaim the role – together with an imagined history – that made her affectionate links the greater: ‘it was not possible to occlude the reality of my relationship with Xavier, the affinities and understandings built over a lifetime’.[14]

Sam Byers, reviewing this novel in The Guardian, makes a brilliant point about the play with racial identities and their recognition or otherwise in relation to roleplay. He weaves his clever perception into analysis of the very texture of the novel’s plot and language, even its parts of speech. Consider this:

“You might think that people wondered how we did it,” she says, describing the comfortable Manhattan lifestyle she shares with her husband. The perspectives are tortuous, unmanageable. Who is this “you” that might imagine their way into the opinions of unseen others? As the novel progresses, these gazes are experienced as social roles both longed for and resisted. “How many times had I been told how much it meant to some person or another, seeing someone who looked like me on stage or on screen,” she says, one of many moments in the novel in which ethnicity is both present and absent at once: acknowledged, but never explicitly named.[15]

This gets to the strangeness and comprehensiveness of this novel’s mastery of genre, form and technique in the novel, that only needs a tweak to see how brilliantly it uses Gothic motifs, especially those of the doppelgänger, where ‘likeness’ is the stuff of desire and threat, love and hate. As with other famous usages, that motif can examine the ambivalence, nay the multiplicities of role and identity that can underly what looks simple, whole and integrated. Not least a role like the ‘mother’. A favourite examination of mine comes where the narrator suddenly questions the naturalness of her feelings and thought about Xavier, at this point acknowledged as her son. Did, she thinks, they have a ‘good relationship’ which Xavier’s new girlfriend Hana queries or is it important that:

… it was also true that there were long periods when I did not seem to think of our relationship at all, when it was as if our relationship did not exist, it did not occupy any space in my mind. Was it normal for a mother to be so unreflective?[16]

That word ‘unreflective’ together with all the other mirrors in the mind or external space in the novel’s naming of them resonates with its concern with ‘likeness’, and claims about the mimetic role of art. It reminds us that the narrator’s disintegration was apparent from the very opening of the novel, where standing outside a restaurant she goes through the entire process which led her to enter into its ‘inside’ – almost revelling in the play of external and internal, object and subject relationships implied by the events.

But then I saw him through the window, seated at a table toward the back of the dining room. I stared through the layers of glass and reflection, the frame of my own face. Something uncoiled in my stomach, slow and languorous, and ….[17]

Glass that offers transparency and reflection to the seer also co-frames what is seen with the seer. This ensures that what she sees is an aspect of herself and how she ‘frames’ the perception of others with interpretation, identity and relationship to her. It prefigures the thing Sam Byrne sees as so significant (and I concur fully) – her perception that Xavier mimics or copies (here we deal with mimesis yet again) her very tics that she uses to resolve problems in the acting of a complex role and which, though familiar is moved into the realms of the unfamiliar (the word familiar of course is rooted in notions of family and home as Freud points out) or ‘uncanny’. Byrne puts it thus:

…, when the churn of movement and syntax is disrupted – appropriately, by the smallest of gestures – a deeper existential dread emerges. Xavier sits back, exhales. The narrator, with a sense of shock, recognises the movement as her own, “lifted from my films, my stage performances, and copied without shame. A piece of me, on the body of a stranger.” Xavier has studied her, she believes, then performed her back to herself.[18]

This is all about ‘doubles’ and their uncanniness (unheimlich is Freud’s terms). Sometimes the doubling and reflection is done quite practically by mirrors that reveal the self as estranged:

I stripped off my sweater and stood before the mirror, my skin was strangely mottled, my appearance repulsive. More and more often , I was surprised by the person in the mirror, it was not the lines at my mouth or the hollowness around my eyes, it was the lag in recognition that was the most troubling, the brief moment when I looked in the mirror and did not know who I was.[19]

The problem with ‘likeness’ is ‘unlikeness, with the familiar, the unfamiliar, the Heimlich, the unheimlich. The world of this fiction is the world of what we might call unfiction, for fiction has often tried to structure the stories told with order, sequence, consistency and integrity but to make character and plot the tools of demonstrating these qualities. Yet that is not how the world is – it has only seemed so long because the fictions told about it (by religions and humanist beliefs) have pretended that this is so. In fact what is to be confronted is a world in which ‘nothing remains stable and untouched’, where reality and performance are not distinguishable and the biggest lie we tell ourselves is that ‘of course, I was not indeterminate myself’.[20] Very often stories and dramas consist mainly of ‘new constellations of old roles’.[21]

Some stories are incredibly fragile – that which is most fragile in the book is the world of stories we tell ourselves of uncomplicated marriages and the hope that comes from birth (or rebirth). This is captured in the narrator’s re-capture of the memory of her pregnancy where abstracts like hope, continuity, rebirth are just like ‘whatever other words you might associate with the springtime of reproduction, even accidental and unintended reproduction’, as in fact a ‘cagey period, where feelings and desires have to be fabricated to meet the expectations of a role. The internal process of this is captured in glowing prose of searing honesty about pregnancy:

Eight or nine weeks. A period long enough for a different reality to assert itself, but not long enough for the seams stitching your old life together to come fully undone. Despite my ambivalence, I could feel my imagination work to take in this new idea, I could feel it twisting and ferreting out new positions, contorting into poses previously unimagined, until it could just about contain the thought.[22]

I cannot improve on Sam Byrne’s final judgement on this book: ‘The result is a literary performance of true uncanniness; one that, in a very real sense, takes on life’.[23] That sentence is almost as rich as one of Kitamura’s – almost, but not quite because she is unbeatable.

Read this great book.

With love

Steven xxxxx

[1] Katie Kitamura (2025: 67) Audition London, Vintage, Penguin Random House

[2] Ibid: 196f. (the final pages of the novel).

[3] Murata Surname – Meaning and Kanji Variations | JapaneseNames.info at https://japanese-names.info/last-name/murata/

[4] Kitamura, op.cit: 43f.

[6] Ibid: 57

[7] Ibid: 62

[8] Ibid: 87

[9] Ibid: 99

[10] Ibid: 42

[11] Ibid: 171

[12] Ibid: 185

[13] Ibid: 99

[14] Ibid: 102f.

[15] Sam Byers (2025) ‘Audition by Katie Kitamura review – a literary performance of true uncanniness’ in The Guardian (Wed 16 Apr 2025 07.31 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/apr/16/audition-by-katie-kitamura-review-a-literary-performance-of-true-uncanniness

[16] Kitamura, op.cit: 160

[17] Ibid: 3

[18] Sam Byrne op.cit, citing Kitamura op.cit: 17

[19] Kitamura, op.cit: 33

[20] Ibid: 67

[21] Ibid: 121

[22] Ibid: 58f.

[23] Sam Byrne, op. cit.

3 thoughts on “This is a blog on Katie Kitamura (2025) ‘Audition’.”