The Electra suite of the Tyneside cinema at 1.10 p.m. on Friday 25th July

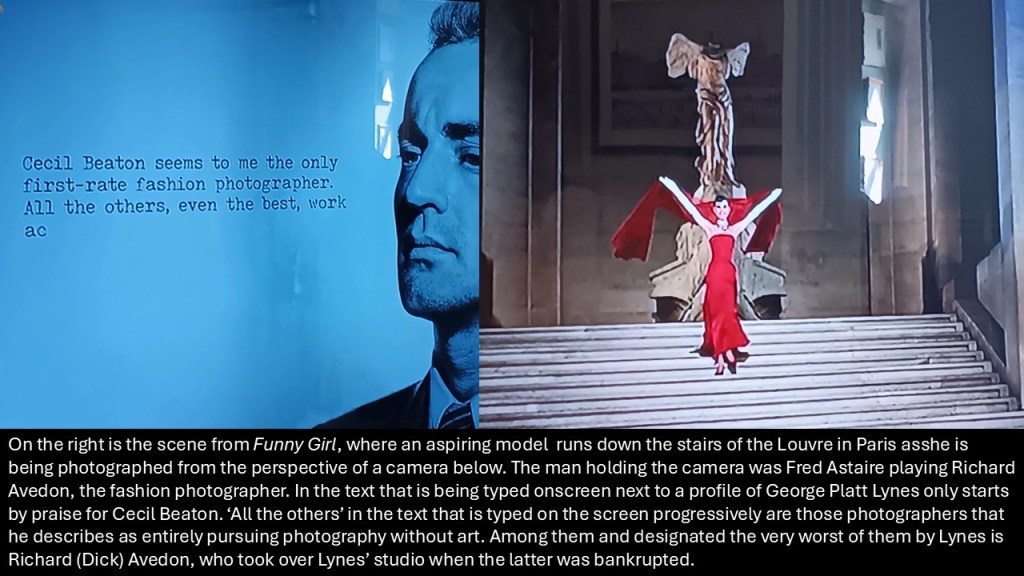

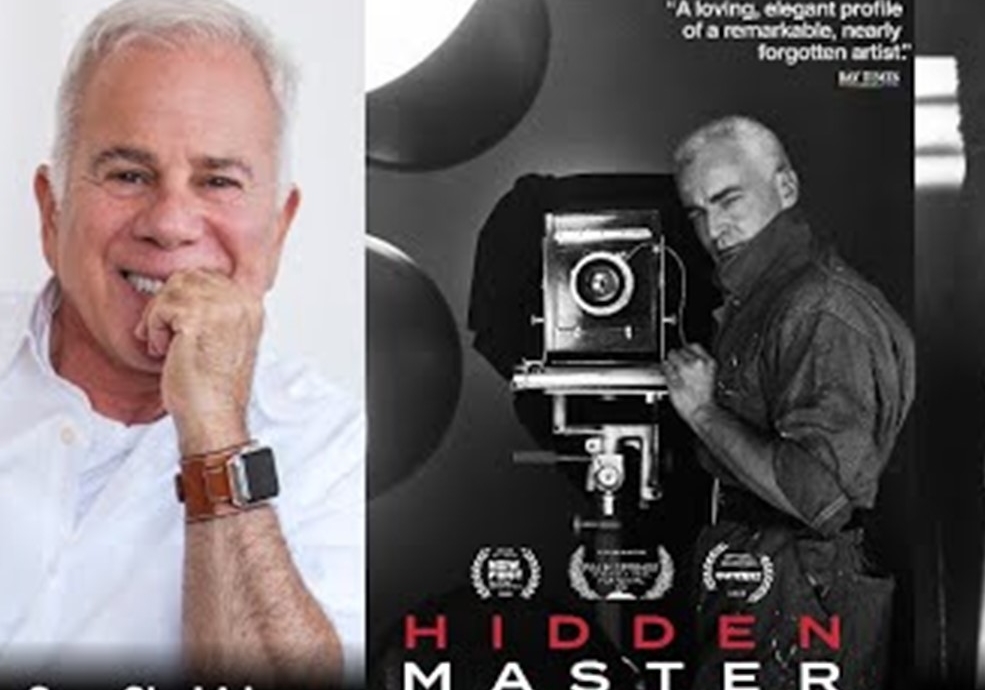

The events of Friday 25th July are a fitting image of an ‘alternate universe’, so I’ll describe those. I had planned to see a new film, one just released in the UK at least,Sam Sahid’s biographical and art documentary of the life of George Platt Lynes, a photographer I have blogged about before (see the earlier blog at this link if you wish).

Our dog, Daisy, can’t be left so my husband Geoff stayed with her whilst I travelled by train to Newcastle. The Electra Suite of the Tyneside Cinema in Newcastle, our nearest art cinema, is on the top floor of the building and I rather trudged up the flights of stairs to get there, arriving about ten past one, the film was due to start at 1.15 p.m. The photograph above shows the cinema suite as it was then and as it remained throughout my time there – empty entirely, an eerie experience when the light goes down and the huge screen plays just for you. Nevertheless, it engrossed me. However, one hour in, the frame stilled and soon after the screen darkened (the shot was one that roved down until it stilled from a male nude to the fireplace on the mantle of which this representation was standing. I waited for the purpose of this effect to become clear but the screen just darkened eventually obviously stuck. Was this act of God or some other moral censor? Why might that be?

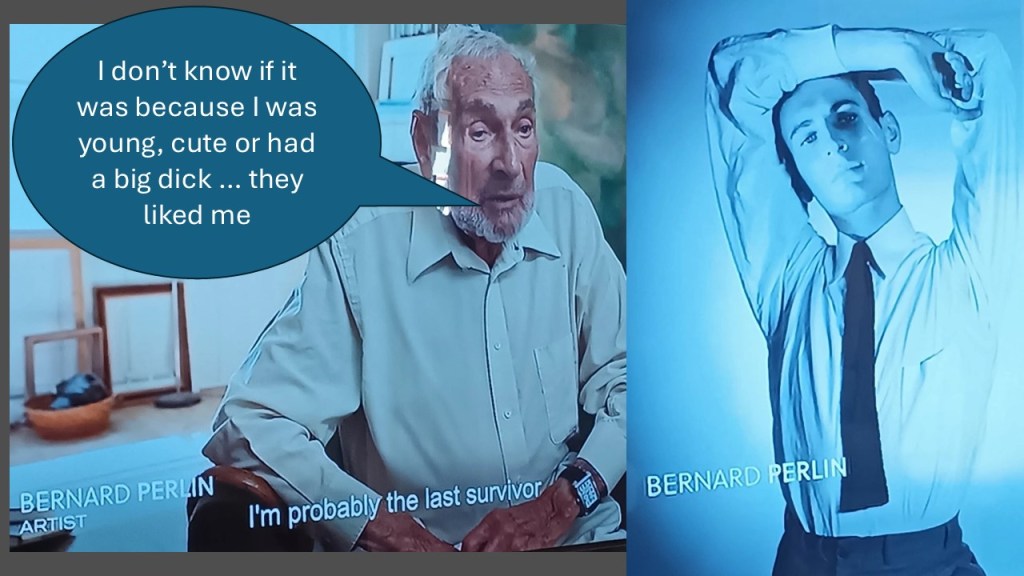

The transcription is of words used by Perlin but from my memory so the phrasing may be awry but the content does represent Perlin’s dry wit as a memorialist.

The story broke up just after the American artist who calls himself in the film the ‘last survivor’ of the the group of queer friends and artists associated with the mid twentieth century queer art scene in New York (who died in 2014 at the age of 95) Bernard Perlin, who George Platt Lynes appointed as the executor of his will and art collection, has told the story of George asking him to place ice cubes ‘up his bum’ and have anal sex with him. Bernard says the experience was ‘memorable’ because of the confluence of hot desire and cold ice and have anal sex with him. Bernard recommended the experience saying it would be good for your friends to have nice memories of you, once you too had died like Lynes did. However, clearly someone on our ‘alternate universe’ found the story or that recommendation distasteful for the film was not to be restarted. Even when I found the usher (a floor below at another screen, who got technicians and the manager on the job, the film, even when restarted was not to got over that moral hurdle of the icy experience of queer male sex.

I went home with a promise that my ticket price would be recompensed (still not sure it has been) and a silly story to retail alternate universes. At home Geoff and I ordered the DVD from Amazon USA (only available there as yet) and we watched it a couple of days ago, my stills – even those above coming from a replay on out TV. But Platt Lynes’ ‘life’ has any way a kind of ‘alternate universe’ feel to it. the story of psychosocial adventure that was the lives of the privileged white elite from which Platt Lynes derived counters most views of the mid twentieth-century as a place in which queer lives were lived in solitude, and with consequent negative affect like shame, guilt and isolation.

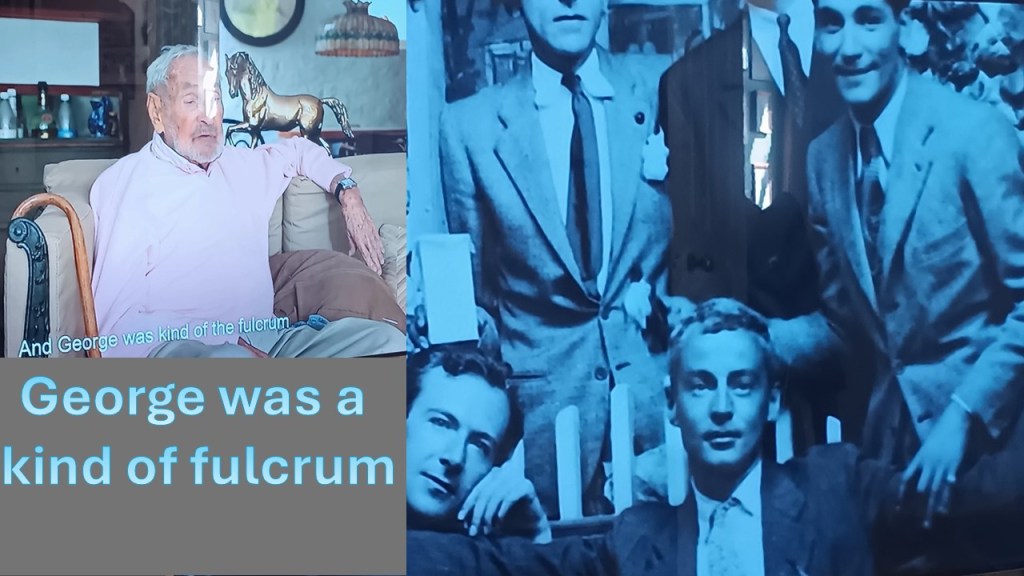

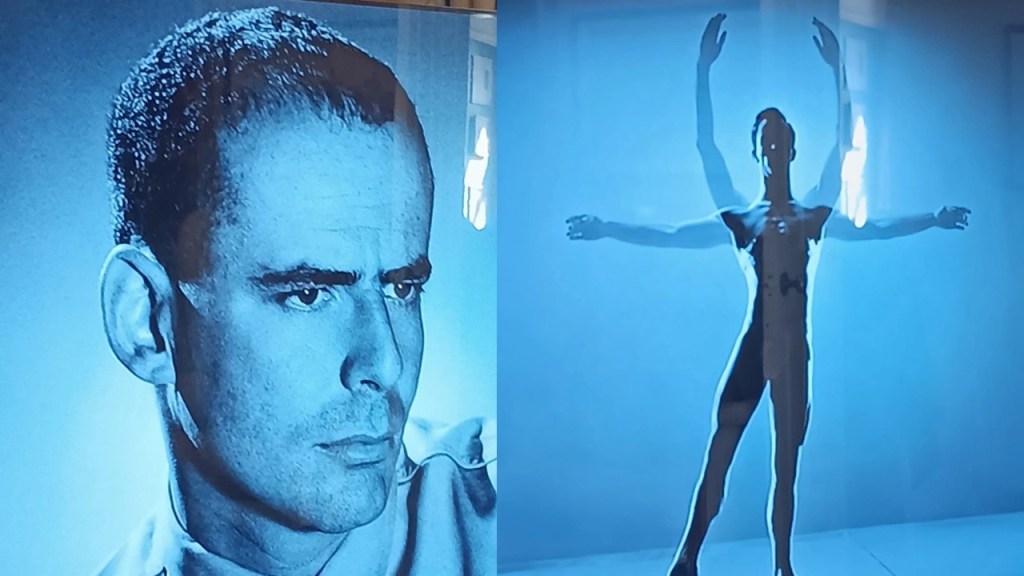

For the privileged few, life was not like that. A brief biography of Perlin on the internet names the members of that few as ‘the upper echelons of New York gay society, a glittering “cufflink crowd” that included George Platt Lynes, Lincoln Kirstein, Glenway Wescott, Monroe Wheeler, Paul Cadmus, Jared French, George Tooker, Pavel Tchelitchew, Truman Capote, Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Laurents, and Jerome Robbins’. Of such groups, plebtigully illustrated in the film, Bernard Perlin says George was the ‘fulcrum’. He certainly appears so in the photograph below where the spread of his arms seems to embrace and pull together a whole group, just as Mary as Mother Church does with the faithful in painted medieval allegories.

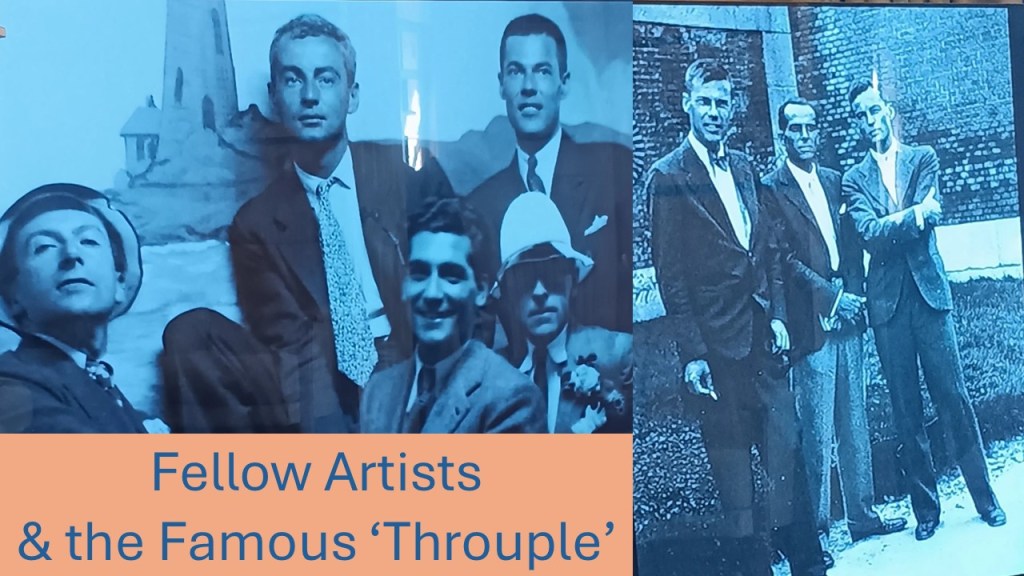

And such groups, however much they threatened heteronormative society and the norms of bourgeois life generally were not as visible to the rest of the world as we may today think, when generalised visibility is more important to our democracies than was the rather structured invisibility of class, gender and race elites in the 1940s and 1950s, where the privileged could live unseen liges as far as people in tne lower classex were concerned. In one way, the ‘throuple’ [the word did not exist at the time] – made up of Glenway Westcott, Monroe Wheeler, and George Platt Lynes and the capacity of that group to give way to multiple affairs, sexual or romantic for each member, could look very like the homosocial alliances white men of the same class made with each other.

As the film narrates, again through Perlin, it was only when George left the throuple that Glenway and Monroe felt exposed as a ‘sexual’ couple to the public eye, and they chastised George for that. Otherwise, the self -sustained groups, often either fluid gender access in public,could pass as groups of collaborating artists. In the photograph below, we see two sets of artists in groups in the collage. Who was to tell the second wax the core of a sexually relating group as well. Moreover, fellow artist groups could anyway cross the sexual boundaries when needed.

Privileged these groups remained, though they had to hide a little more under the McCarthyite witch-hunts for the Homintern tendency – a tendency dreamed up in the imagination of the USA-Anglo right wing that united fears of Communism and ‘organised homosexuality’. The retreat of Fire Island, even just before America’s entry to the Second World war, I have touched on before – recently in relation to Platt Lynes friend Paul Cadmus (see the blog here) but the large homes of the elite were sufficient – the film shows for parties that extended through every room including the bedrooms.

Everything was camp and joyous in this world, in the way that is always the case in worlds built on the artifice made possible by unlimited funds – or a belief in them. Moreover, both sex and art were related aspects of the fun, money, and power made available. In this film, one queer art historian Jarrett Earnest emphasises that art nor shared sex were not conceived as paradigmatically different. Both are life with a capital F for fun in the middle. They emphasise the choice of the three names of Paul (Cadmus), Jared and Margaret (French) as an appropriate name for shared art that was playful, the name PaJaMa, to show that art as happening on a Fire Island Beach, and then reproduced in photography and paint was all a kind of ‘pajama party’. If you looked to art to fund existential threat, they continued, you won’t find it here, just groups enjoying themselves and how they clothed (or didn’t) their bodies.

But fun still depended on money and status. The film makes it clear that, despite the fact that the fashion for his photography had faded, in favour of new dynamic pictures, like those of Richard Avedon (whose career was even captured for Hollywood movies) of fantasies based on mobility rather than the stasis of art favoured by Lynes (and his English friend, Cecil Beaton), Lynes continued to fund lavish homes and parties to fill them, well beyond his budget (budgets, after all, are so ‘bourgeois’ darling!).

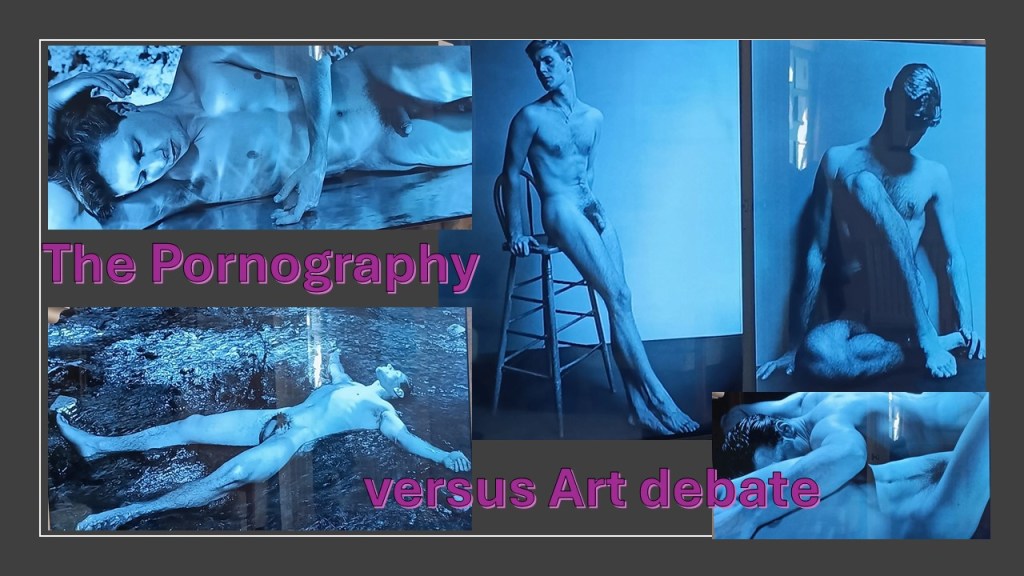

And up to this film, art history has been unkind to George Platt Lynes too. His taste is considered nichely queer (at the extreme as a kind of over-hyped pornography or worse a joke) and even a brave film like this stuffed with art historians offering warm opinions can have waspish reviews in The Guardian and be regarded as praising Lynes’ art merely in order to please the financial needs of his estate to accrue profit and the ‘queerness’ of the current set of distinguished art historians, even if that ‘is not to say that Lynes’ work is not worth exploring’. But do not explore him as the outcome of mentoring by Man Ray or as a precedent for a figure like Robert Mapplethorpe.

After all, I think Lynes black gay nudes far less oppressive than those of Mapplethorpe, which in their most famous example metamorphose a Black model in a suit into the enormous phallus that protrudes from his fly, feeding mainly (in my opinion of course) mainly the oppressive mythologies of overlarge Black penis size (even if the intention was to satirise the myth), the dangers of which myth in white hegemonic cultures is explored by Obioma Ugoala (2022) The Problem With My Normal Penis: Myths of Race, Sex and Masculinity; a book I blogged upon at this link.

Lynes’ trans-racial or solely Black male lovers are not, it seems to me, used for the purpose of such divisive dangerous mythology, but to set a standard of Black male nude beauty that would defy those who wanted to differentiate the races on moral and aesthetic grounds. In the picture below there is no exhibition of the penis, the lover at the back, who suddenly notices the gaze of the camera, has his groin obscured by the beautiful rise of his lover’s buttocks. This was quite beautiful in the cinema – rather spoiled above by the reflection of our living room on the reflective surface of our TV.

Of course penis size mattered to this group as I examined in a blog (at this link) on the novelist Glenway Westcott – one of the privileged poly-amorous trio of which Lynes was a part, with Monroe Wheeler – just as it did for a later generation of Fire Island queer men (see my blog here on Andrew Holleran). But if there is racism, it does not lie here – for the ‘art’ (both the literature referred to immediately above and George Platt Lynes) depended upon cuteness being associated – almost to the point of oppression – with white penile visibility. Indeed it is this feature of the nudes that is usually discussed in debating whether Lynes’ photographs are ‘art’ as he saw them or pornography – if a very refined version thereof. Here are examples from the film collaged.

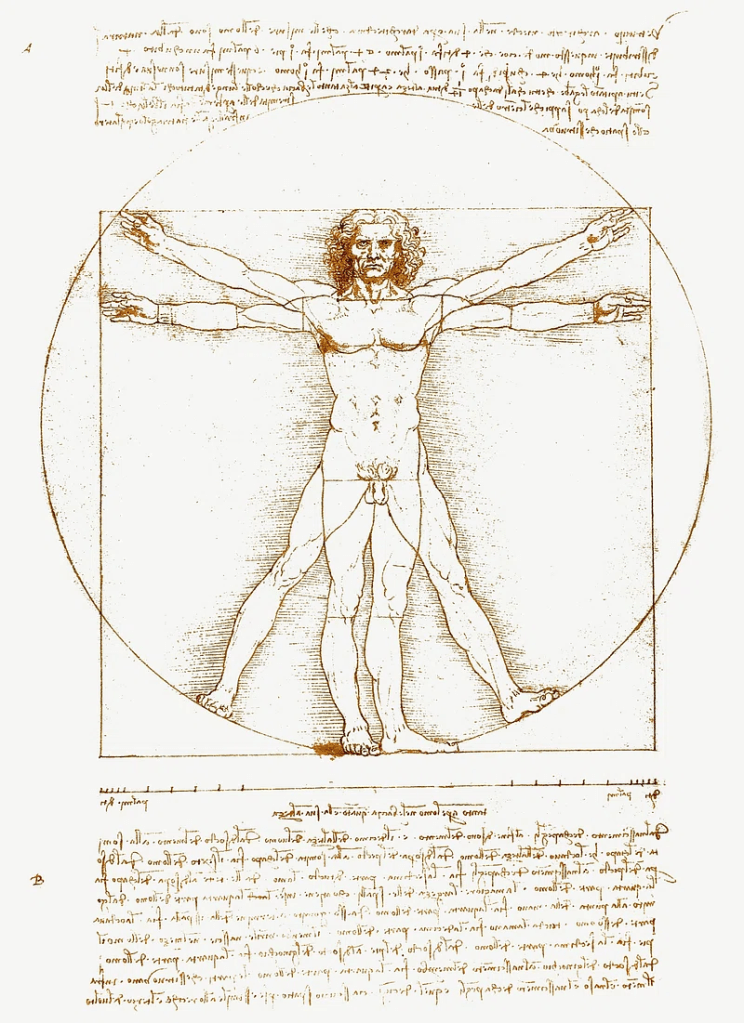

In my own opinion, these works tell us more about the tactility of skin – the touch, for instance of ambient water or anticipated from a hand imagined by gazing at one’s own – often what matters about sexual organs is their capacity to lie in patterned configuration of limbs touching each other or to semi- or fully-erect from such touch – even in a single nude figure. The lie of a man’s arm on another man’s naked torso has the same quality of tactility or haptic fantasy in a viewer. Given the way the pose of the man in the picture on bottom left above mimes that of Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, the issue of penis size resolves into a debate about proportion and the nature of male beauty.

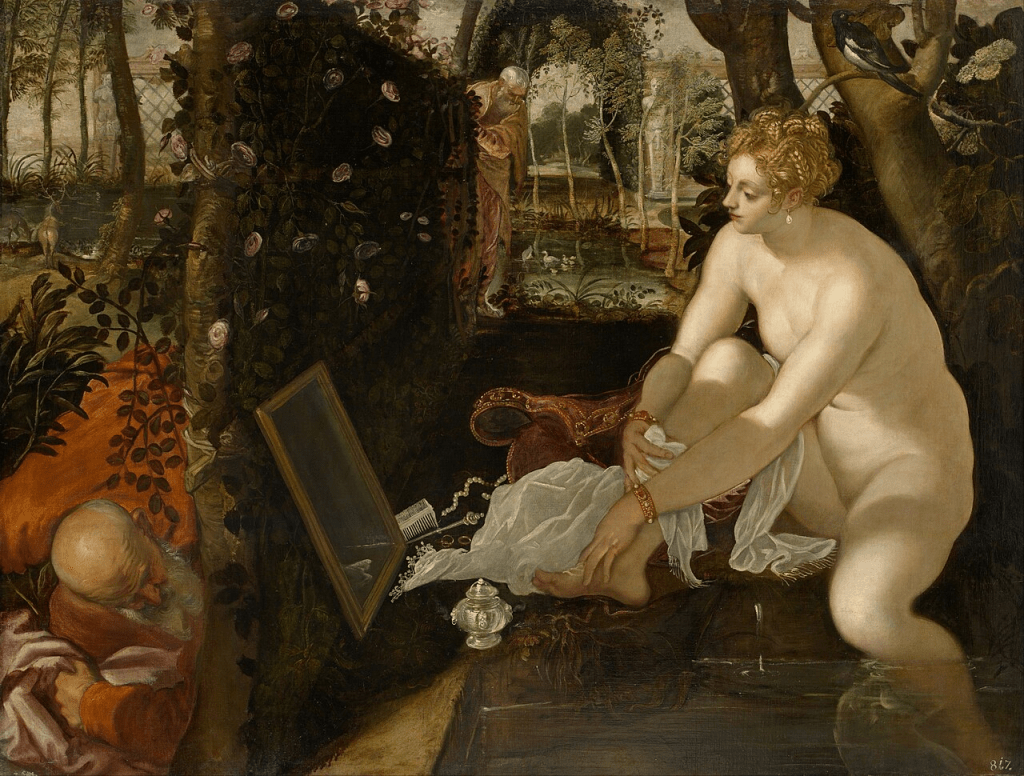

Of course, artistic and aesthetic concerns might mask pornographic interest – that has always been an issue in the representation of nudes that was made clear in Susanna and the Elders, especially as captured by Tintoretto, where even Susanna can be imagined a pornographer, as she can’t in Artemisia Gentileschi’s versions.

Of course art, as in Tintoretto, can precisely raise the issue that point of view and reading from that point of view of an image and its context, can make art mean different things to different people or to the same person at different times or in different spaces. Is this the point Lynes makes in placing his stretched but apparently sleeping (and perhaps therefore unconscious) youth next to a crude picture of an Orphean lyre. Of course the photograph exploits the myth of Orpheus (see my blog on this at this link) but even that myth is dependent on the realisation of the vulnerability of the beautiful to the worst of us and its wildness. Nevertheless the point about touch is my responses still – even the touch of fingers on a badly represented lyre. However, this collage raises other issues.

The style of male beauty in the 1940s and 50s (for a blog on a source for the fuller history, see this) is not that of today. Muscularity and toning are less important than youth so that a layer of fatty tissue or its apparent complete absence, together with the absence of muscle, seems alien to our notions. But though that might have a bearing on the Orphic image above, it does not on the sequence photographs in little on the top left. Here, a man is exposed in a manner that shows his ribs, the posture intended to emphasise his penis. The next two seemed pictures show the process of removing underpants. Are these pornogrsphically over-focused on one part of the body alone. They suggest the photographs have to be examined each in terms of its likely function as an image bearer. And that is how it should be.

Yet though I am a great fan of George Lynes, and more so of his place as a spokesperson for a queer set – of artists exploring the freedom that the contingency of their birth gave them – his articulation of some of the set’s themes is less nuanced than some of theirs – certainly true of Westcott – but more so of Paul Cadmus. In my blog on Camus (linked here again) I associated him and Auden with a nuanced view of what it means to seek beauty that goes to wards via detours to ‘ugliness’. Here is what I said:

… Cadmus is insisting that we examine our notion of ugliness for our role in its production, pulling from it those imposed ideological factors to find the root of what fascinates us in ‘ugliness’, some of which will be an attraction to the beauty that co-exists with it. Moreover, that task is a moral one – it is about being willing to expend the energy to see the world from varied viewpoints where categories don’t determine beauty or goodness but genuine human interaction does. It is the same task that Tolstoy sets himself – to shapeshift between human perspectives, or Dickens, or Forster, and not allow prescribed classifications to read for us what is beautiful and too easily equate that with what is good. Presumably syphilis is beautiful when we take the chance to really look at it as a human experience and not just class it as a ‘sexual disease’ and sign of disorder – only seen in order to be eradicated. Similarly moral prohibition overeating should not allow us to see every instance or token of a fat person as ‘ugly’. This is an issue Cadmus takes up in his painting where one fat person makes herself ugly mainly in the manner in which she views the fat peace-seeker sat next her with his pregnant wife.

There is an analogue in poetry here. In Auden’s Lullaby, the lyrist sings to his lover aware that much of his ‘Individual beauty’ has been burned away in age and sickness BUT though ‘mortal, guilty’ of the world’s sins, he is the ‘entirely beautiful’ because I allow him to ‘lie’ (in both senses of the word) just as all ‘living creatures’ must lie, next to someone who meets their need for warmth.

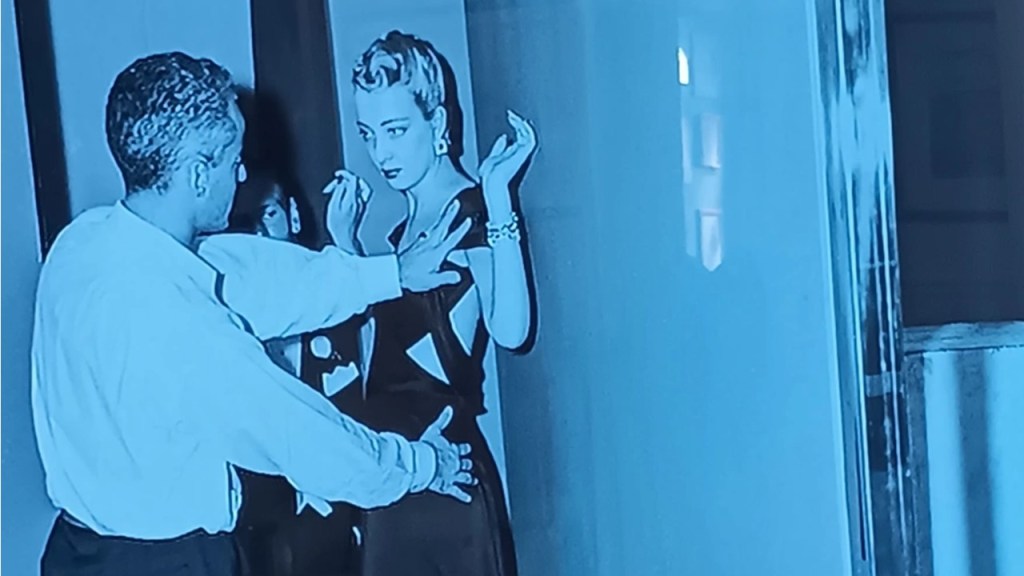

I don’t sens this nuance about beauty in George Platt Lynes. Like a boy reading John Keats for the first time I think he felt his responsive attraction to beauty was about the discovery of truth – Keats was much more nuanced than that in his work, not unlike Cadmus. Lynes saw beauty where it was in what attracted him but he sometimes failed to see what its pursuit excluded in his life I think. He also failed to see the ugliness in some of his behavioural response to beauty – thus the sources of both are limited in him. I see this particularly in this photograph relating to his one serious sexual affair with a woman, whom – this film tells us – he demanded have sex with his other friends so he could photograph him at any time. This happened to Perlin and is one of the stories that led to him calling George ‘a devil’. In the photograph below, George’s handling of the lady is brutal, possessive and, I think, abusive, as he poses her – just as he did in the sex games he played to cause interaction between different sources of beauty – male, female, environmental and so on.

To him beauty must have seen formal – and all the better when stilled, as if by Keat’s Grecian urn or his detailed close shots. Many witnesses in the film describe him as too secure in the beauty that he had the status to choose from out of the range of it at the upper end of what he must have seen as a scale. He knew he was beautiful, and his self-portraits seemed of that aspect of him alone, whatever his age:

THe gaze into the eyes of the viewer is entirely possessive, perhaps because it renders his eyes capturable for possession by the seer too. His love for Monroe Wheeler (whom he took over as main lover from Glenway Westcott in their throuple) was very deep – at least from the evidence of his writing, even in telegrams. One of the latter (in the collage below) sighs to Wheeler:

ALL HERE IS WIND AND WISTARIA (sic.) AND I LONG FOR YOUR SHADOWY / BEAUTY

His other letters and notes particularize love as dwelling in that beauty (and the night – like Byron’s view of love). He is ever ‘the boy’ looking up to his man. The film shows us the Valentine of collaged photographs he gave to Wheeler as a Valentine and which Wheeler kept on his bedside table, even after George’s departure. Its charm is of an entirely boyish beauty offered to a man – often through the eyes.

He could appreciate the complex nuanced take on what love relationships might be from Colette (he photographed her as he did so many European major writers) but did he stay a pouting boy in the process?

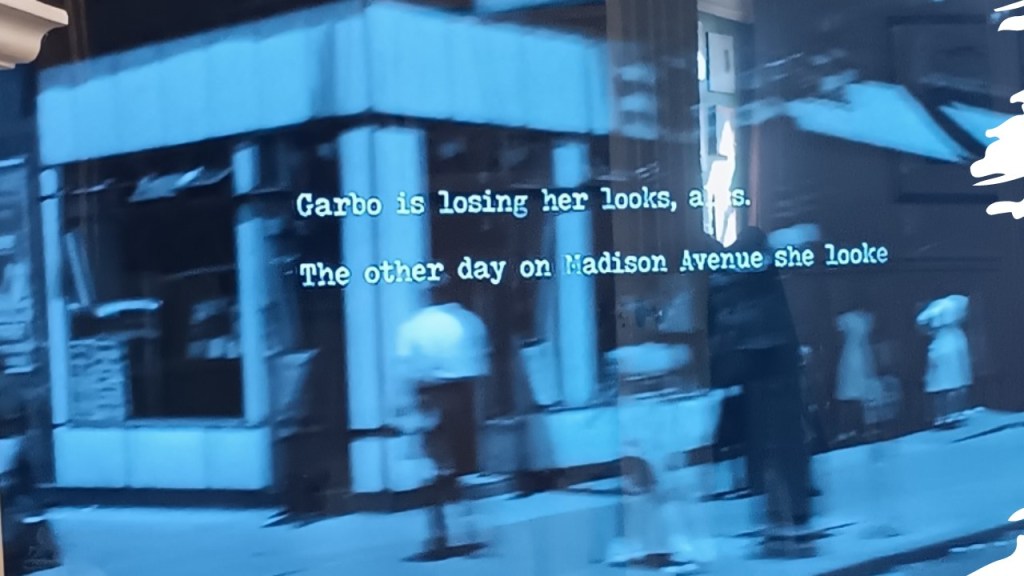

AS Perlin tells us, of his case that ‘George was a devil’, his actual relationships with artist-icons tended to become sour and catty in his private report of them, as in the case below where his text is revealed as if being typed in talking about later meetings with the aging Greta Garbo. His main concern is that: ‘Garbo is losing her looks’.

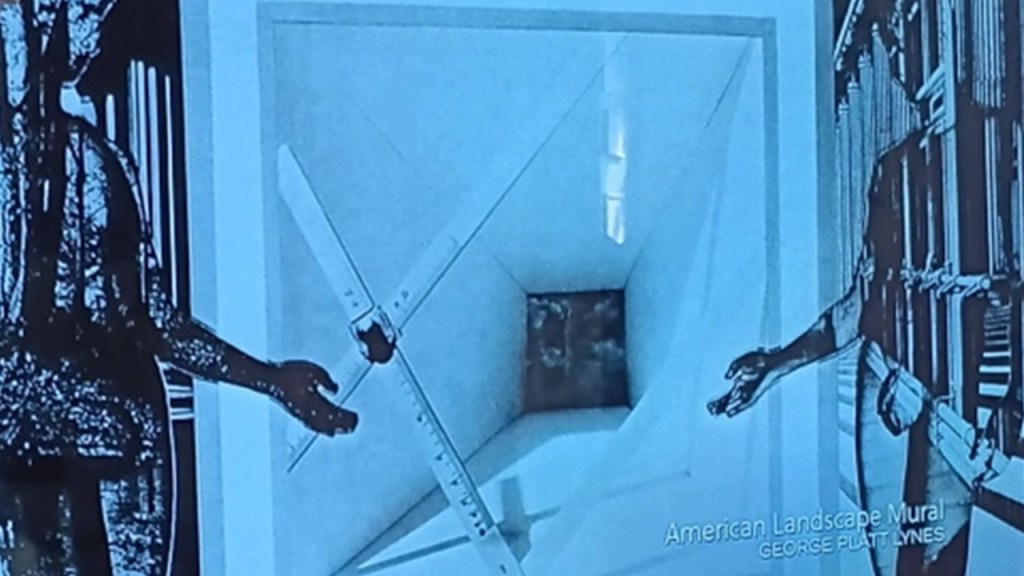

As the story is revealed, it ends with her surveying what George believed were his best and most beautiful celebrity photography and others but only being interested in the ‘big dicks’. There is some power of over-interpretation there, I think. When, under Man Ray’s obvious tutelage he experimented with allegorical existential surrealism, his interest was in beautiful people each being locked away from the other by rulers, regulations, bars and locks, so that neither sees the beauty of the other though the figure on the left – filled with natural landscape extends a hand to the genitals of the figure on the right.

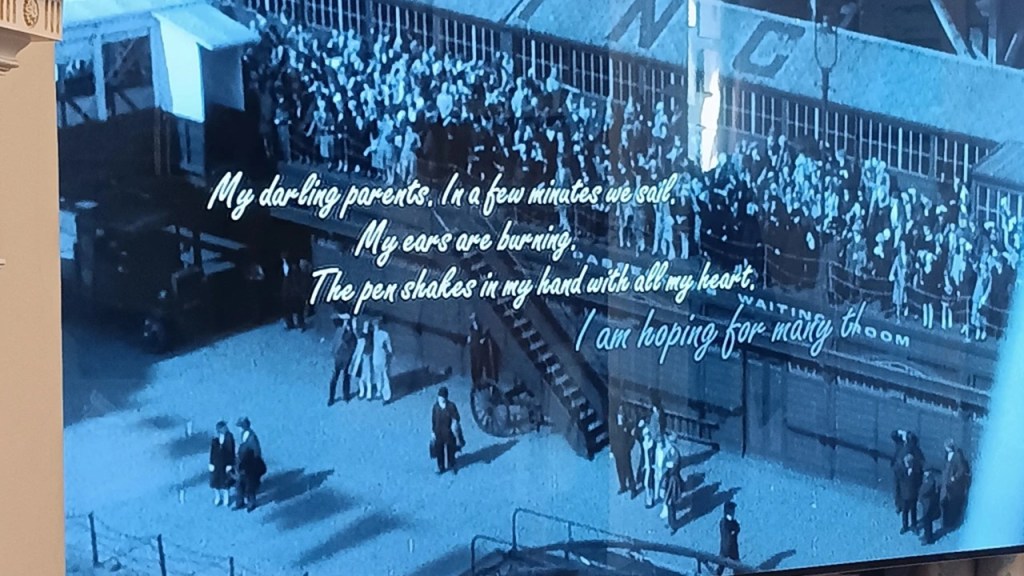

When George set off to Paris for the first time by steamer – having sold a first edition gifted to him by his father – he went as a writer and he devoted himself to writing ‘beautifully’ even to his parents.That his ‘pen shakes in my hand with all my heart’, could be a model of how he saw writing as emotional transcription by the medium of the pen, collecting the anticipations of experience from the rest of his body. I can’t remember but I think the first edition was of Keats, or was it Hardy?

In his later life, when he was involved with the stunningly beautiful Lincoln Kirstein, who married Paul Cadmus’ sister but later had her incarcerated, and he became the official photographer of the New York Ballet set up by Kirstein, his interst seemed to be in creating a sense of bodily motion (as the hated Dick Avedon did), not as illusion but as a collage of overlaid still moments in the beautiful body of beautiful men.

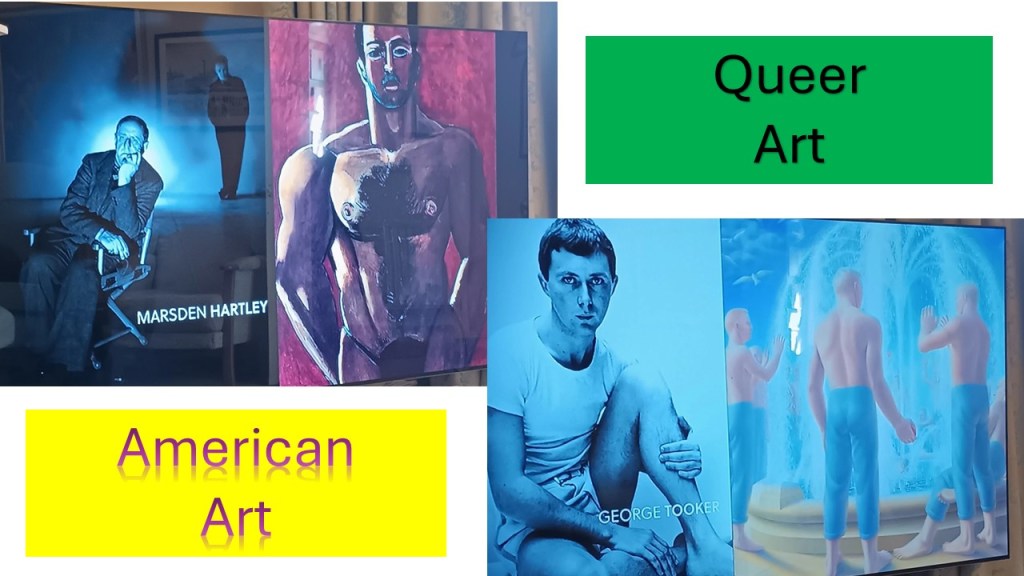

He collected artists whom he thought reflected his unitary love of uncompromised beauty, though most had variations on that theme – see below (with examples of their art: The grand queen of queer art, Marsden Hartley, Paul Cadmus, and George Tooker.

He pumped the heart of the art that was exiling itself in New York, fast overtaking Paris as the global centre of art – From Auden, Don Bachardy (Auden’s lover), and the grand Pavel Tchelitchew (at that time thought to be the heir of Picasso).

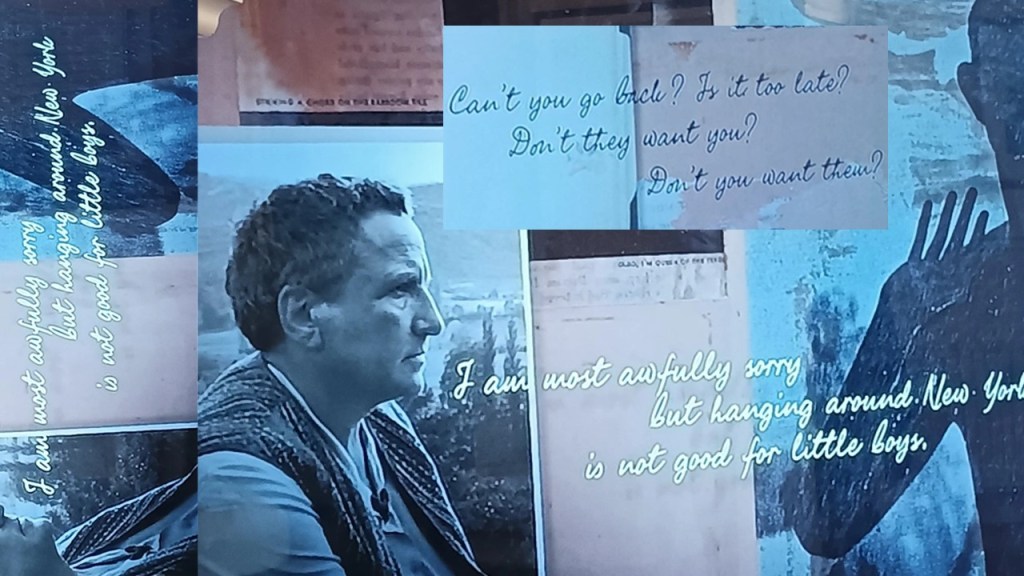

None of these characters would ever be as honest with him as Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas: in Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (see my blog here) – actually her own autobiography – she calls him ‘Baby’. George furiously attempted to get the ladies to drop the ‘Baby George’ epithet only for Stein to double down on seeing him as a ‘little boy’ searching for pleasure amongst the cocks of New York – those especially attached to beautiful artists.

Above, she urges him to go back to Yale rather than set out with other credentials into the world of art and sex. Saying ‘hanging around New York is not good for little boys’ must have hurt somewhat – a lot I think. Stein might have a great deal to teach George of art but do babies or little boys ever listen. My sense is that the grand ladies played with him as they did their dog, Frou-Frou, though she was sincere in preferring him as her ‘official photographer to Man Ray: of him she said to George she was ‘sick of his airs and graces’.

That’s all I have, I suppose. I won’t ever give up on George Platt Lynes for his need for beauty needs to be at the centre of a queer aesthetic I think. But maybe wee hold on to him as to the ‘boy-child’ we hope might one day learn something that matures us all with real learning. That is there in George Platt Lynes I am sure. If you know him, or of him, or know him not at all, this film will please:

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

See you in some other ‘alternate universe’, if I ever get to one that is not an empty cinema.