If we assume that ‘work’ is something we can do whilst our attention is divided in listening to something quite unrelated to it, what really is the value of our work? This blog reflects on the exhibition ‘With These Hands’ at the Laing Gallery Newcastle seen on 15th July 2025.

Raing at the Laing yesterday (Laing is correctly pronounced as if it were spelled ‘Lain’, of course)

With These Hands is an exhibition currently on in the Laing Gallery in Newcastle. During the first rain for some time, I visited it yesterday whilst waiting for an event in the evening – an interview with Gurnak Johal, the author of Saraswati (2025) – I mention it in an earlier blog that is linked here. But the exhibition is worthy of more than filling time – though as I only arrived at 3.50 and, unbeknownst to me the staff begin clearing the building at 4.15 for cl9sing time, this was a brief visit – thankfully I get reduced entry to exhibitions (50%) as an Art Fund member.

But listening, or not (or indeed doing anything else that divides attention) is very much an issue in the representations in this exhibition. The Laing’s own publicity describes the show thus:

With These Hands explores the representation of craft in paintings, drawings, and prints. The process of making and mending by hand whether a domestic pastime, rural and semi-industrial labour, or essential war effort, is a persistent theme to which artists return. Yet these artworks are rarely straightforward observations of everyday activity. Instead, the act of making is used to symbolise personal and communal identity, leisure and work, tradition and progress.

Produced in Britain and Europe from the 1750s onwards, these images reflect a society undergoing immense change. The growth of industry, the reorganisation of the methods and places of work, the changing status of women and the conflicts of World War I and II all impacted the value placed on hand skill. Some artists were interested in capturing traditions – their works romanticising crafts they perceived as almost lost – while others were drawn to the atmosphere and activity of the workshop and factory.

With These Hands takes you from refined drawing rooms to weaving sheds, from a woodland saw pit to an inner city carpenter’s shop, and from country blacksmiths to industrial forges. It focuses particularly on the changing role of making in women’s lives, the relationship between craft and community, and its impact on our landscape.

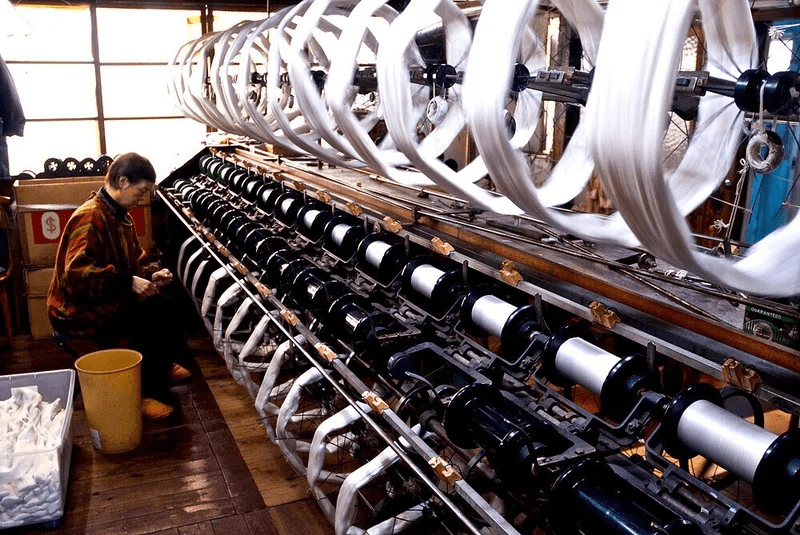

Reading this do you feel as I do that you want to say: slow down a minute and tell me exactly what the art you want to show me ‘represents’ in ‘paintings, drawings, and prints’. For ‘craft’ is a loaded word and not everyone will identify what we are asked to recognise in this exhibition as ‘craft’; as is somewhat given away by its contrast with ‘the atmosphere and activity of the workshop and factory’. Factories when I was younger never piped music to workers because of the probiting noise of the machines – I am thinking of the textile factories of West Yorkshire then, far too noisy to hear anything above them and hearing problems in later age were common in mill workers – my mother worked in a quieter area – in the spinning room but the noise of even industrial yarn spinning was still deafening to my young ears and finished my grandmother’shearing permanently:

The nub of the issue though is what in the description reads thus: ‘The growth of industry, the reorganisation of the methods and places of work, the changing status of women and the conflicts of World War I and II all impacted the value placed on hand skill’. Hand skill is often termed differently to produced a hierarchy of the ‘value’ attached to it, in ascending order something like this (imagine the word ‘manual’ – from manus – Latin for ‘hand’ in front of it as a qualifier): labour, work, craft, and then art.

Manual labour is seen as the least demanding of ‘skills’ or activities (other than regulated and patterned uses of the hand) – even if the patterns took considerable strength and energy in their performance. Did this allow for divided attention? The pattern of industrial injury from the nineteenth century onwards until the end of the heavier type of Northern textile industry suggests not, and nowadays, it is difficult to even imagine the noise made in a weaving shed of the mid-twentieth century. ‘You could hear nothing‘, my grandmother, Elsie Bamlett said, ‘not even your own thoughts’, not that, she added in rebel irony in a Yorkshire accent, ‘the overlocker’ [as she named him – presumably ‘overlooker’ or foreman] ‘thought that his workers had any thoughts worth listening to’.

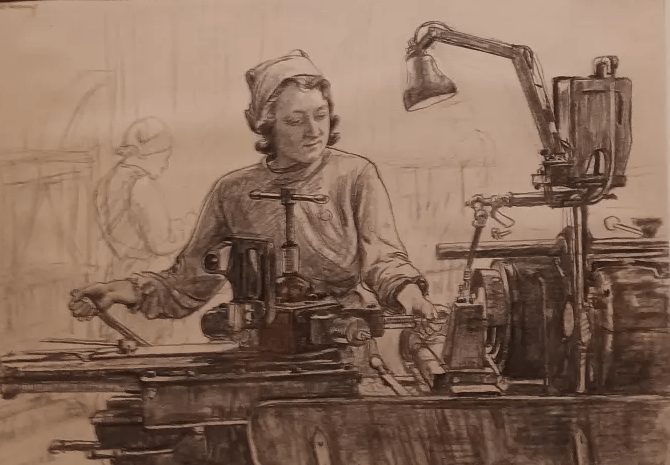

But can you hear the machine here [in the picture from the exhibition below] anymore than the stilled and empty factory above – or can the ‘machinist’ even hear it, or anything else except that special kind of silent music: “the still sad music of humanity”, as Wordsworth called it.

Take into account that the picture above was for a war poster encouraging middle-class women to work in the mills. It wasn’t new to have women in the mills: just read Mary Barton (1848) to check that out. The novelty marked in this print was that this is specifically not meant to represent the past and normative type of female mill-hand? The attentiveness of the woman represented is interesting for it has become a necessity for war artists to present manual labour as the craft it possibly is rather than the manual labour it seemed to most forced to do it by economic circumstances alone. This may be because the need was to attract to it those middle class married women not accustomed to thinking of paid work outside of the administrative type done before a succesful marriage (one within the ‘respectable’ middle class).

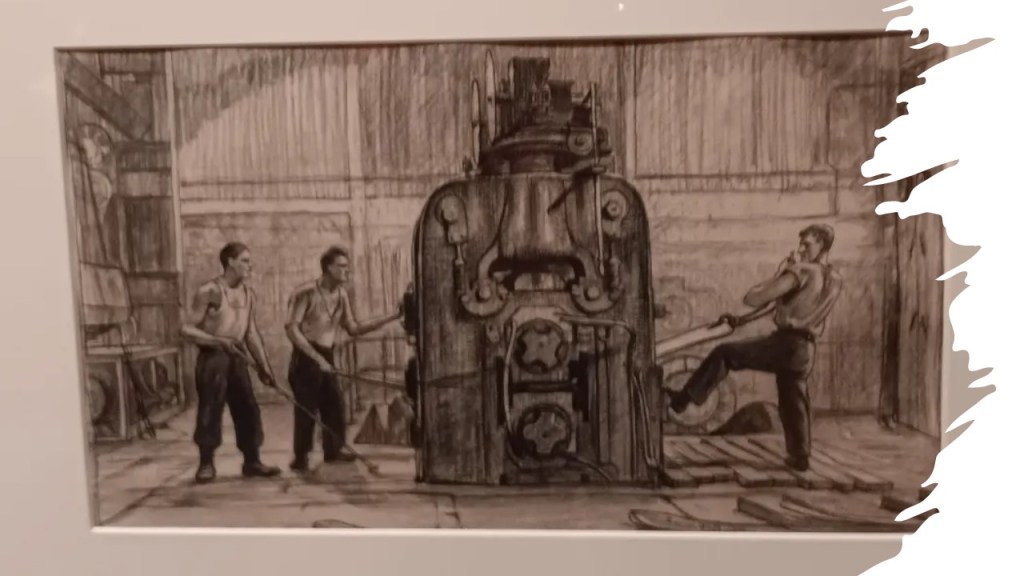

The illustration attempts to depict mental concentration as a part of the skill in machine-based engineering tool work. This lady is good at her craft but is clearly not defined solely as a worker. In contrast, this is not the case in the illustrations below where the brute strength of males in manual labour matters more than any necessary skill, though the tasks all needed both. The difference is that illustrations below are of male industrial workers (the first are French men) and the primary aim is not to make the work look attractive and worthwhile as a means of passing one’s own time, or indeed particularly individuated, but as a necessity of a succesful economy.

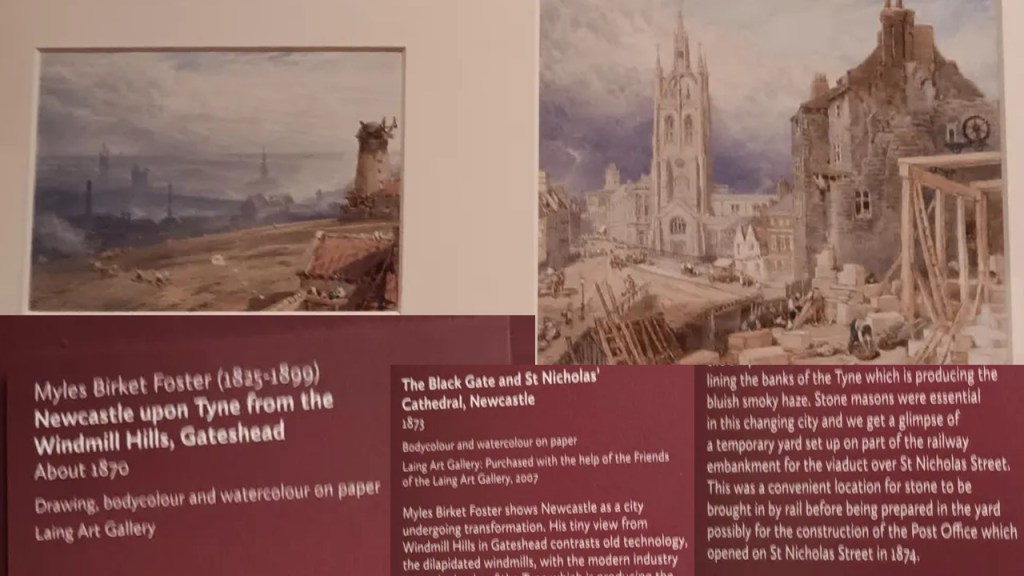

In the last example above the male hands are clueless of what they individually might do other than in waiting for their role to commence within a regular prescribed script for their work, idle when their muscle is not called upon. Not, of course that the passing of the olden days could not be celebrated in a nuanced way, as it is by Myles Birket Foster in the local Newcastle and Gateshead views below, which did not stop short at showing the filthy disadvantages of industrialisation but did not make the antique buildings of older ages or otherwise wasted land look attractive either.

Manual work has been differentiated from manual craft from the very beginnings of recorded history, although the Ancient Attic Greeks did not include the crudest manual work in the definition of a male citizen’s self-definition, many tasks (in war for instance) called precisely for that. At home most dirty manual work was done by slaves not citizens: what citizens did (and was valued as meaningful work – and what came to be named in English ‘craft’) was described in the the word τέχνη: Here, as defined by Wikipedia, the use of the distinction in determining hierarchies of value.

In Ancient Greek philosophy, techne (Greek: τέχνη, romanized: tékhnē, lit. ’art, skill, craft’; Ancient Greek: [tékʰnɛː], Modern Greek: [ˈtexni]) is a philosophical concept that refers to making or doing. Today, while the Ancient Greek definition of techne is similar to the modern definition and use of “practical knowledge”, techne can include various fields such as mathematics, geometry,[3][4] medicine, shoemaking, rhetoric, philosophy, music, and astronomy. / One of the definitions of techne led by Aristotle, for example, is “a state involving true reason concerned with production”.[1]

The melding of ‘reason’, or the mind (Nous [νοῦς] )- or mind, with manual labour is what makes work ‘craft’. Manual labour, by the way, is not all of the picture – it is just that the advent of the working class as we shall see in nineteenth century novels like Charles Dickens Hard Times (or Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton) came with the peculiar facility of calling that class in terms of their industrial function, ‘hands’. It might be more accurate to call it ‘muscle labour’. The association of muscle with class is more strongly enforced in a culture of waged labour than of slave labour because slaves were visibly subordinate socially, even though they could become skilled teachers of the young.

Howevet. craft itself was by the nineteenth century, as it was not for Classical Attic Greece, subordinate to ‘art’, though the Greek had no separate term for the latter. Anything done by a human, rather than a god or a demi-god and hero, of the type of Heracles, was techne (τέχνη), meaning craft, art, or skill. It was a significant concept often explored in relation to human ingenuity and its consequences, both positive and negative (as my AI tutor says) by dramatists like Aeschylus, for instance, who use it to highlight the power of human knowledge and its potential to shape both progress and destruction in figures like Prometheus (not a human but allied to them unlike Zeus) in his play Prometheus Bound, to contrast it with divine wisdom. It is very like the distinction that might later operate to distinguish craft and ‘art’, the latter being associated by the Romantics, like Goethe, Wordsworth and Coleridges with acts analogous, if not the same, to divine creation. However, Aeschylus also uses skills like metalworking, shipbuilding, and even the art of persuasion to illustrate the multifaceted nature of human techne.

In the nineteenth century too, Socialist Romantics like William Morris, and to some extent the less socialist Pre-Raphaelites, but certainly their champion, John Ruskin, looked to the Old English term handcræft “manual skill, power of the hand; handicraft” (the definition given by etymonline.com) where skill and talent – issues of spirit and mind – combined with manual labour do muddy distinctions between craft and art, just as they were muddied for Attic Greeks, since:

The sense expanded in Old English to include “skill, dexterity; art, science, talent” (via a notion of “mental power”), which led by late Old English to the meaning “trade, handicraft, employment requiring special skill or dexterity,” also “something built or made.” The word still was used for “might, power” in Middle English.

But not all dexterity could be conceived, it was thought for an artistic purpose: whether you thought the function of art was chiefly on the one hand that similat to moral philosophy, truth or absolute beauty, or, on the other, of lower needs such as those purely practical in society or, if not practical, of entertainment for children or the childishness immature in adults. Some pictures just pose this problem even into the twentieth century.

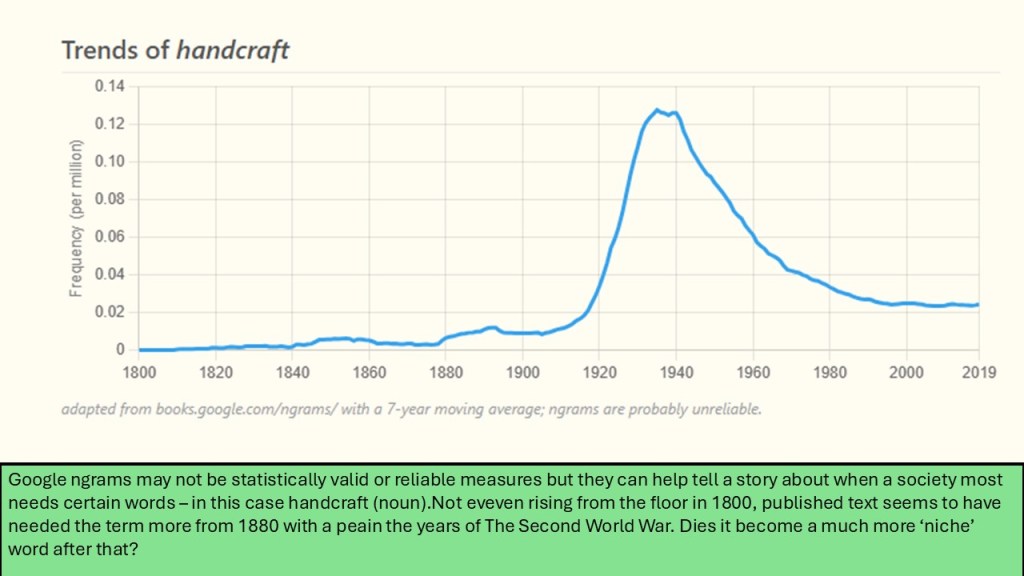

These are the issues which associated how one used the term ‘art’ or ‘craft’, as different or related terms, in the nineteenth century. Whilst the aesthetically centred (Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde for instance) separated art from lived practical life as much as possible, the new Social art movements of the late nineteenth century saw art and life brought together in communal needs. This theme was to be invoked well into the twentieth-century, as the ngram below perhaps evidences.

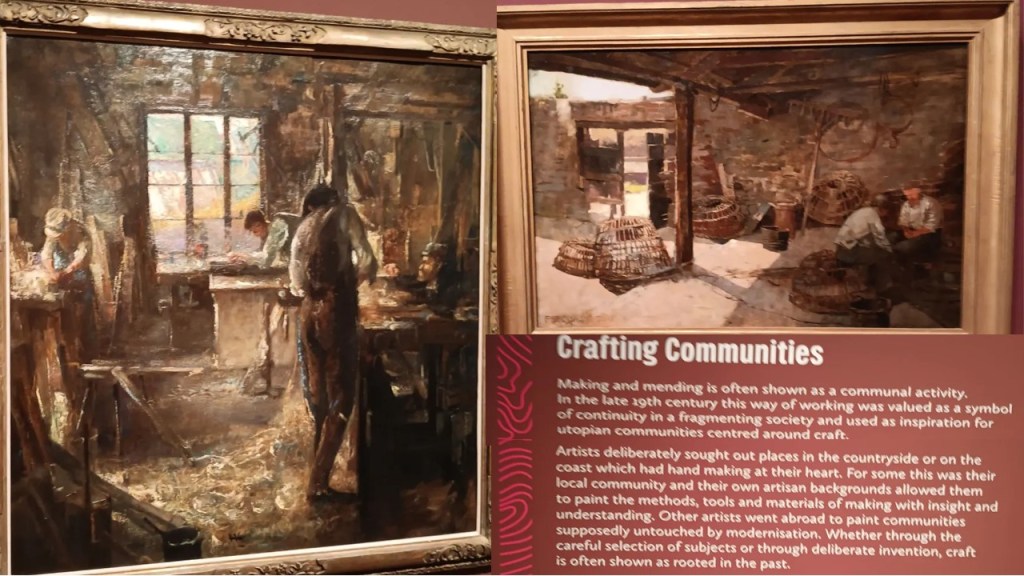

However, more frequently the idealisation of the craftsman (always a man) was in terms of an elegy for a world that was being lost; a stable society where the lower orders were contented (as it was used for instance by the Leavises (F.R & Q.D.) in literary criticism with their constant references, from 1923 at least, to George Sturt’s The Wheelwright’s Shop), taking evidence too from George Eliot. This is how this theme appears in the exhibition, although it is particularly noticeable how much this theme and its communities privileged men as ‘crafters’ in the beginning of Room 2 of the Exhibition (Room 1 being mainly about craft as a sex/gendered as well as class subject.

It displays this idealised images of contented (unalienated) workers by ‘hand and by brain’ (a belief in real ‘crafting communities’ (on which idealised versions engineered by Ruskin, though temporarily in his case, and William Morris were based) along one fabulous wall of the exhibition at the top of Room 2:

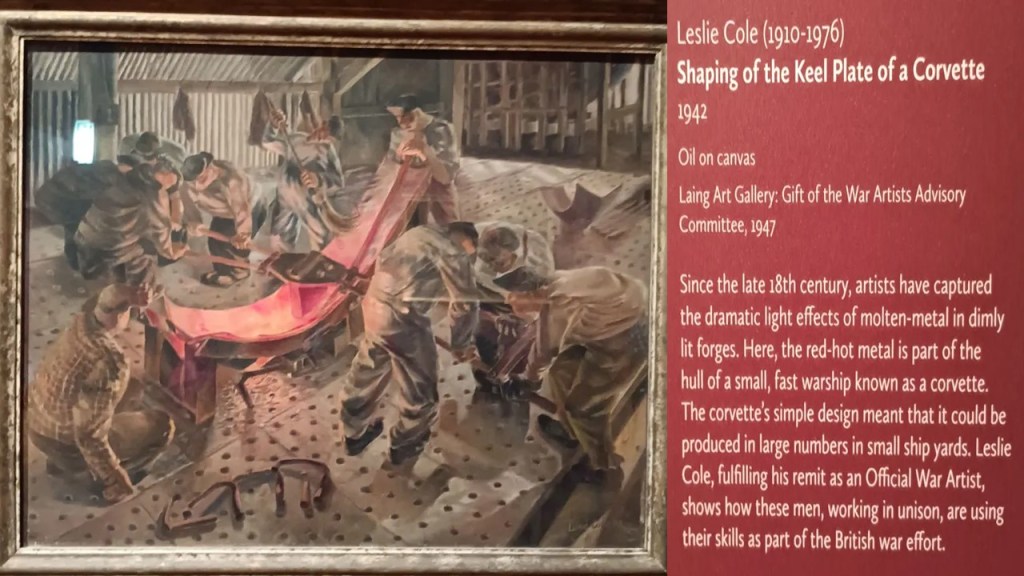

War artists were ready to extend this version even into idealised images of hand labour organised into the feel of a co-operating and participatory team craft, as below, almost as an image of the nation.

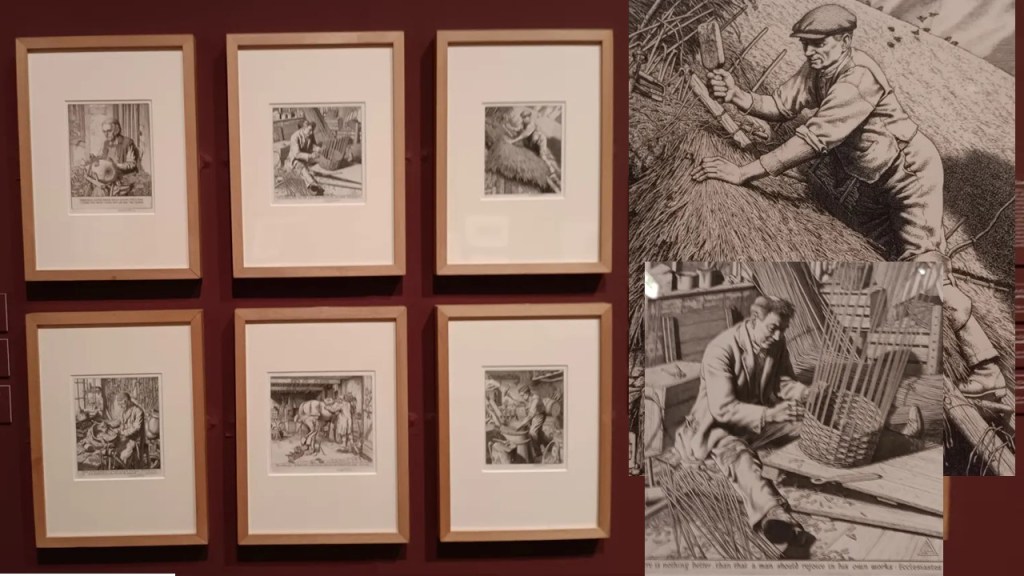

That individual male crafts mattered too was fuelled by this backward looking version of Englishness – which in Lucky Jim, Kingsley Amis saw as the reason for the longing in academics for a theme of a medieval Merrie England, always spelled thus, as a fantasy of being a medieval term itself. Some sketches of contempoary Merrie England male crafters existing into the twentieth-century illustrate the theme in Room 2:

Such imagery could model not only the value of hands put to good use and guided by mind (nous in the modern sense even) but that of an ideal image of authority, sometimes bathed in romantic haze as below:

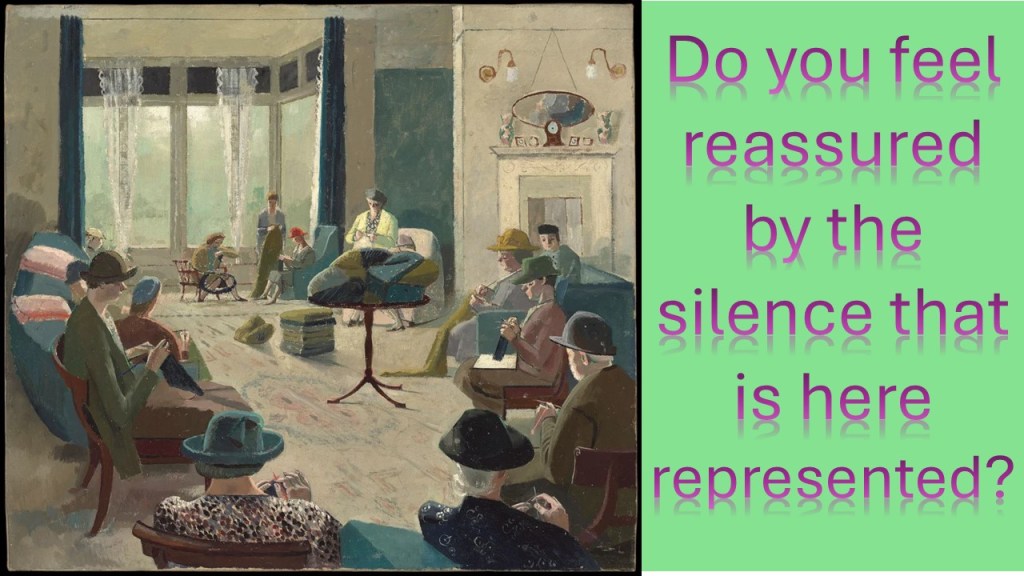

Male authority gave even working-class elders value in the eyes of the picture-buying bourgeoisie. And this authority is not to be frittered away by showing craft either in an individual or a group – merely passing time in the activity, and sweetening labour by listening to something that distracts them. See the question I pose in the collage below. If I were to answer it myself, I would say that the silence pictured – silence but not stillness for the hands of the men sewing sails seem to have some remnant of motion – is authoritative of a guarantee of the quality of the work done. It benefits from the oneness of the group.

Looking at another painting – of women sewing for the benefit of the nation – I did not feel I could answer in the same way, for there is a deliberate way in which these ladies have clearly differentiated themselves from each other – collaborating perhaps, but only thinly. There is something terrifying about a picture in which most of the most visible characters have their backs to you and are not just ignoring your gaze but refusing it, and not only because they are concentrating as the sailmakers are but because they are locked into a kind of reserve they feel necessary to their self-esteem as women.Whether ‘craft’ or ‘work’, it is entirely individualised – none-communal even though superficially there is a community. Of course, my reading could arise from a kind of internalised misogyny and I think there is indeed an element of that in a society framed by patriarchal values.

After all, we do not have to dig down deep to see that women engaged in crafts are often in some sense suspect, repressing a desire or wish that is destructive rather than constructive – the myths of such women (even back in Judaeo-Christianity as Eve and Lilith) stretch through Medieval romance (in the myths of the betrayal of Merlin by countless female student sorceresses to Tennyson’s magisterial version of Vivien’s betrayal of him. Arthurian Romance painting of the late nineteenth century always created a nuanced air of threat around ‘crafty women’ like The Lady of Shallot.

This occurs at the same time as women become associated with decorative interiors – another function of The Angel of the House, as conceived by many but notably and lately in the century by Coventry Patmore. This must have been gruelling for women doing hard-heeled craft weaving:

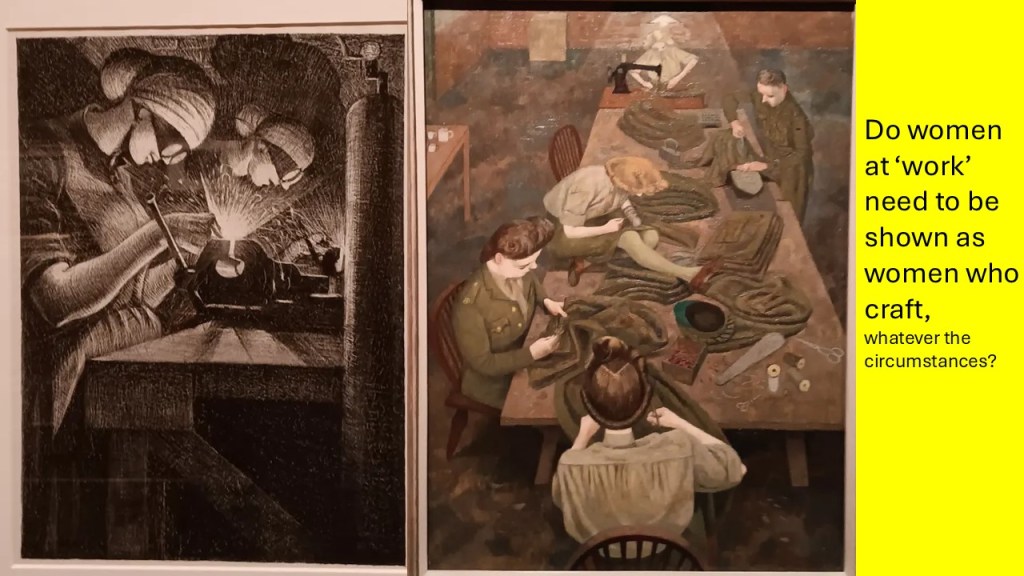

Among the most interesting pieces in this exhibition are war artists representations of women (see an earlier blog on a Laura Knight exhibition, amongst other twentieth century women artists) at the Laing at this link). Below, are examples of war work where women, as their subjects, are treated as being as as serious workers as men, and engaged communally in work and craft – and not least in art representing them. In the collage, the piece on the left is by the fabulous artist, Christopher Nevinson – but the exhibition makes it clear that even this male painter probably exploits stereotypes of women as craftswomen, even though pictured in welding. These women could be sewing neatly and compactly. Whilst in the example on the right, whilst the women are working on military uniforms , the task is still sewing and the femininity of the subjects emphasised, even though the downward point of view removes from them any hint that they encouragement the gaze of others on them as sexual objects.

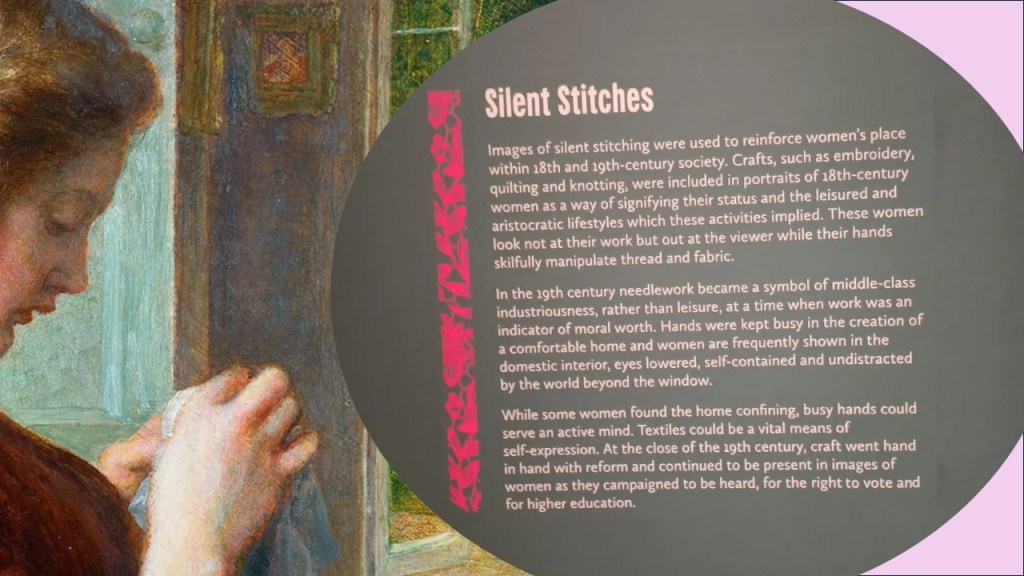

This takes us back to Room 1 and to the arguments there about how female behaviours were sometimes symbolised by the requirements of individual handcraft. Solitary silent stitching, the curators tell us, encapsulated a theory of female passivity with any dangerous activity in women absorbed in silent bonding together of things – stitching things together.

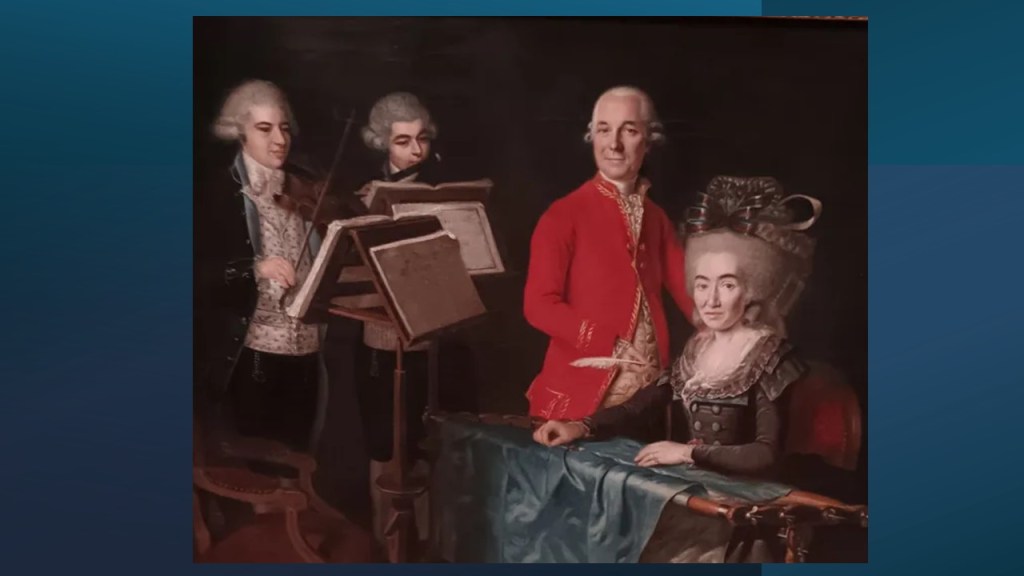

The example here shown is by G.F. Watts. See the whole picture below for it is both beautiful, and, truth to say, suspect. The blush here tells much of how women are moulded into models of safely viewed sexuality, to the point of voyeurism in men.

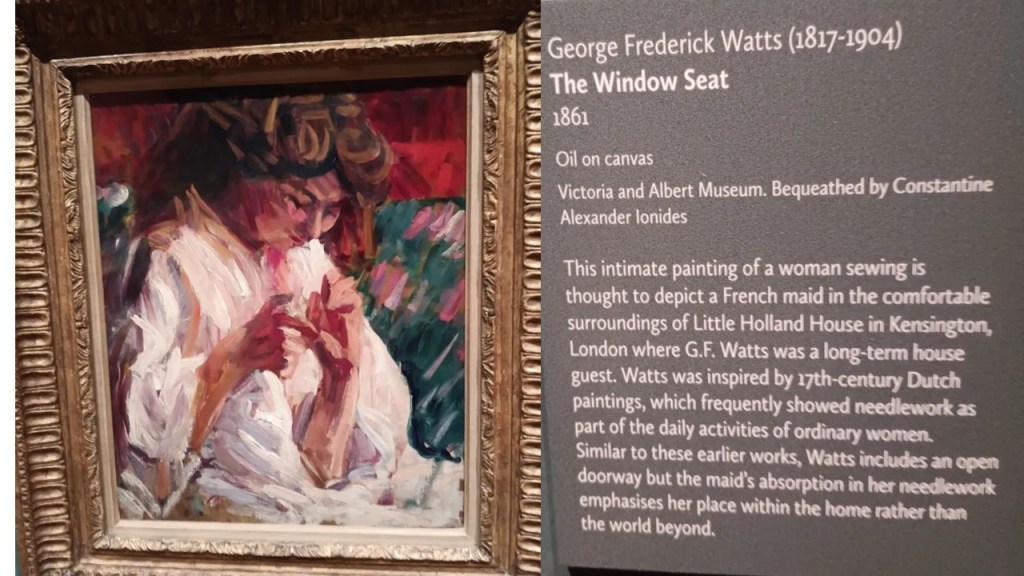

In as far as the model above is sexualised though, she must be unconscious of it. Hence, the blush must not come from the knowledge of being viewed – or worse of slyly returning that male gaze. From the seventeenth century, sewing becomes a model of good female behaviour, and samplers sewn by little girls themselves have laboriously stitched moral axioms on them. A modern version of stitching even self-satirises this iconic function in Room 1.

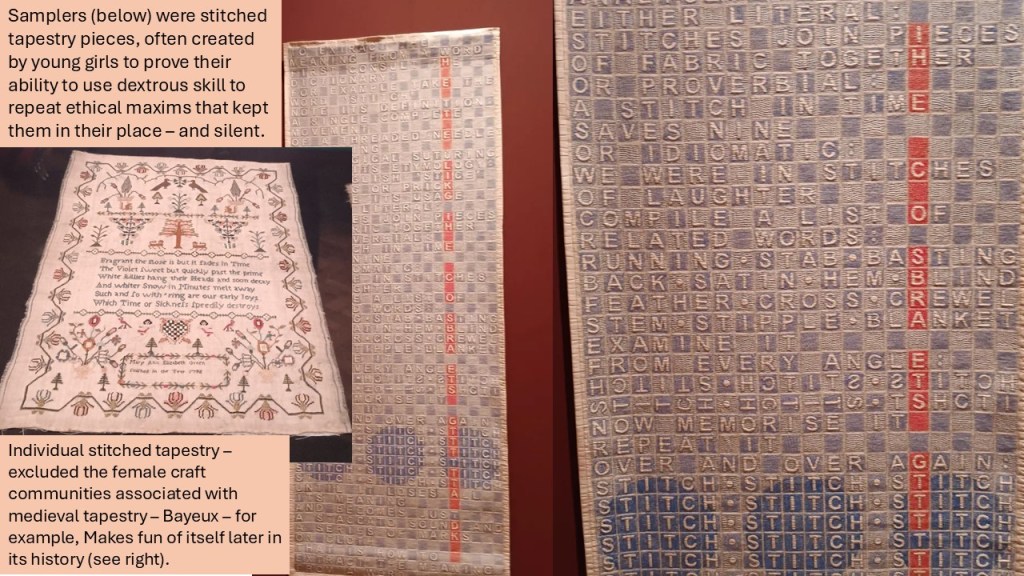

Whether such work or craft was ever allowed to pass as ‘art’ of the higher order established in male traditions of evaluation is uncertain. The eighteenth century example in the exhibition shows a great lady sewing in the company of men engaged in music, the most iconic of arts. But does companionship of arts also intend to show equality of them? I think not. . I think that everything, even the slant of her work table, marginalises the import of the lady’s contribution. What do you think?

And when men paint women silently stitching the sexualisation is even more apparent when there is a larger power differential between man and woman. Consider below a painting by G.F. Watts of a maid in his household. There is something Watts wants to show as suspect in this woman sitting in full light in a window seat.

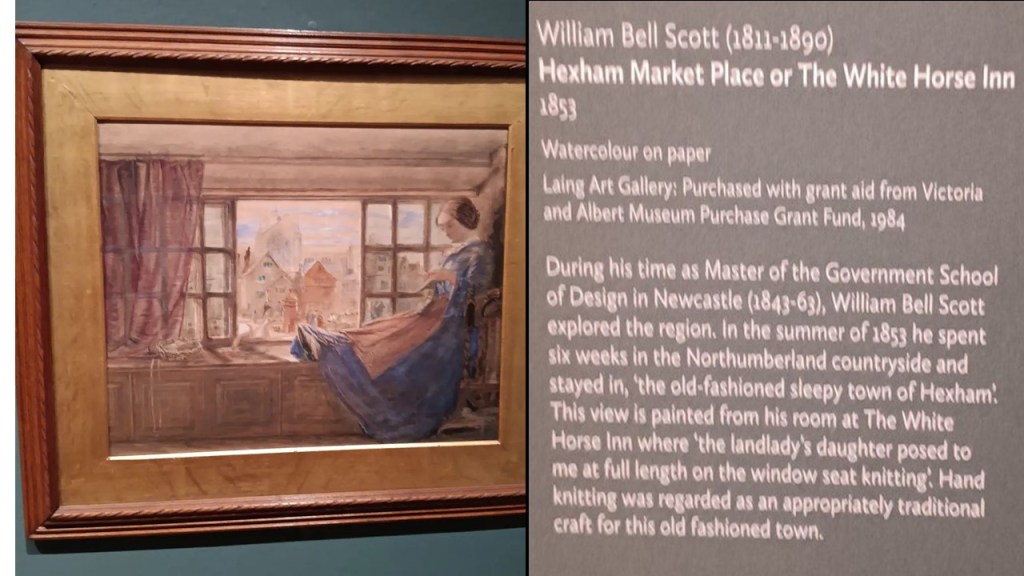

Although less obvious, this is even clearer to me in the picture below by William Bell Scott of a young woman, a pub landlord’s daughter, posed in full view in a high window over the Market Square at Hexham. Here, a woman uses the excuse of craft to make herself famously seen. It is a similar theme to that of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary.

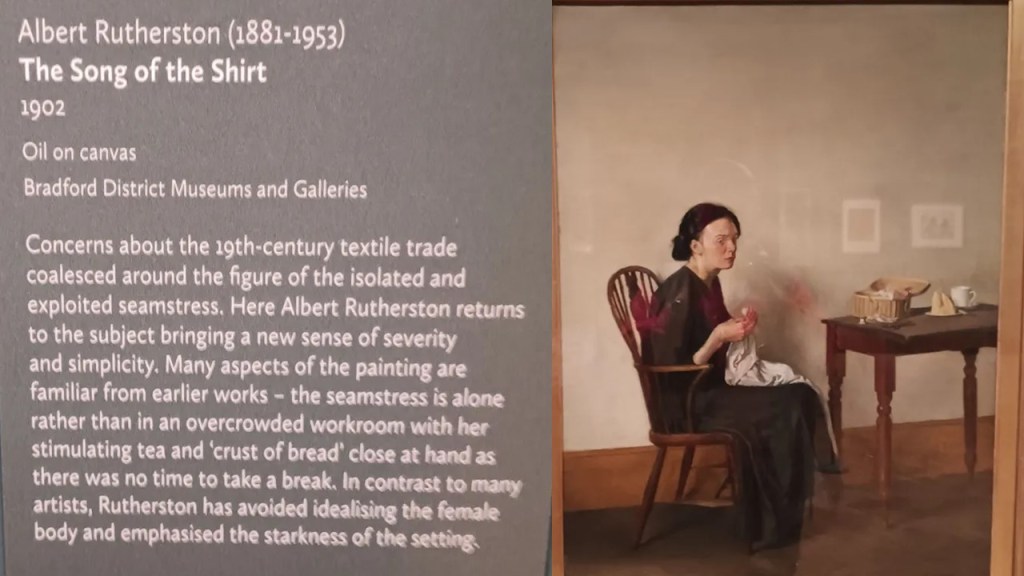

Middle-class men here consciously abuse working class women, although I am sure they would describe it as merely the pursuit of available beauty equated with female youth, ready and willing to accept the attentions of a gentleman artist. But that is not the whole story, for the fate of working-class seamstresses was a major theme of nineteenth century art, not least because of the poem The Song of the Shirt by the radical poet, Thomas Hood, imprisoned by the government for his role in politics. The poem references common knowledge and reports of seamstresses forced into prostitution by the law returns of a craft that refused to be anything other than manual work. This early nineteenth century theme is still being rehashed in late nineteenth century art where working women are painted as starving women, who gave already told the art prints they once possessed leaving dirty marks on the wall – a kind of reference to prostitution.

Craft is not consistent with poverty as the comparison between the paintings of older women below show. The painting on the right shows a woman’s silent stitching lasting into older age as a pattern of industrious morality. In genteel poverty, she has no need of money to compromise that craft. But the elder on the left is marked by the signs of poverty in self and environment. Her downward look is more of shame and frustration than of engaged concentration. Given the chance the woman on the left may need the distraction of divided attention though she could not afford it. The lady on the right is too content to be listening to anything at all.

No doubt my attempt to make thus review of an interesting exhibition answer a WordPress prompt in an overly nuanced manner fails in everywhich way, but I do pursue here lots of things that matter to me, however I’ll I express them.

All for now

With love,

Steven xxxxxxx