Perhaps poetry has it both ways. The Golden Lads of Peter Forster, a Queer Engraver in Wood, seek adventure: Byron like Batman as we shall see. They do so though only in the ‘security’ that the poem that embodies them will last against wear and other thefts of time. Forster’s Golden lads haunt The Folio Golden Treasury : Peter Forster on Shakespeare, Byron and W.H. Auden.

Peter Forster 1934-2021

Golden lads and girls all must, As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.

So says the fine elegiac lyric from Shakespeare’s Cymbeline. And from dust can gold ever be resurrected? Perhaps enough to gleam the richer though stored in a golden treasury.

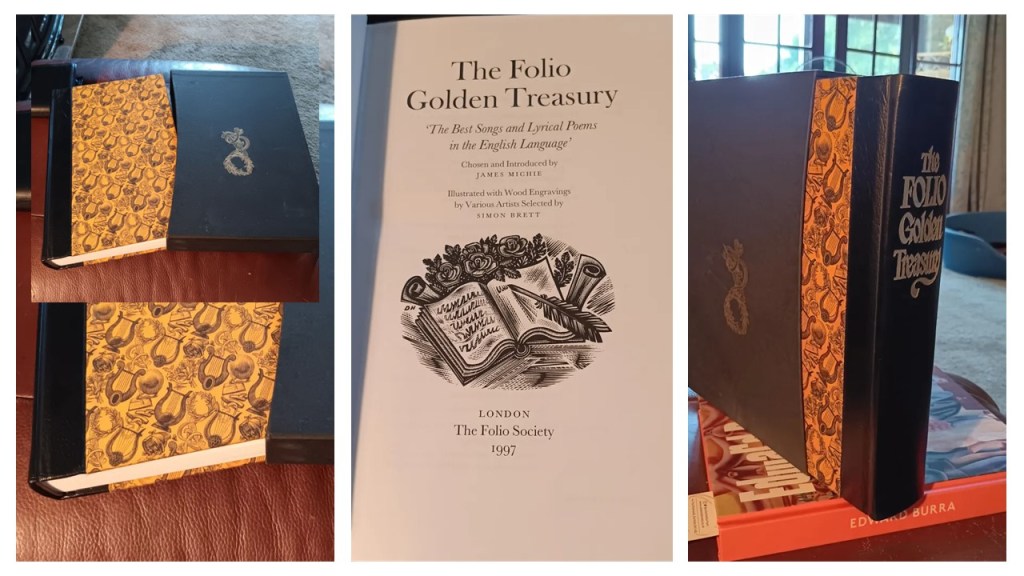

The Folio Press book pictured above was a conscious updating of Palgrave’s Golden Treasury of English Verse by James Michie with Simon Brett acting to select already published illustrations from the Folio repertoire as well as commission new ones. (See the Folio library tribute to him at this link). The volume first came out in 1997. I found one in The People’s Bookshop in Durham and bought it on the strength of one self-conscious queer illustration to a Shakespeare sonnet (number 110 in the canonical ordering).

To me, fair friend, you never can be old,

For as you were when first your eye I eyed,

Such seems your beauty still. Three winters cold

Have from the forests shook three summers’ pride,

Three beauteous springs to yellow autumn turned

In process of the seasons have I seen,

Three April perfumes in three hot Junes burned,

Since first I saw you fresh, which yet are green.

Ah, yet doth beauty, like a dial-hand,

Steal from his figure, and no pace perceived;

So your sweet hue, which methinks still doth stand,

Hath motion, and mine eye may be deceived:

For fear of which, hear this, thou age unbred:

Ere you were born was beauty’s summer dead.

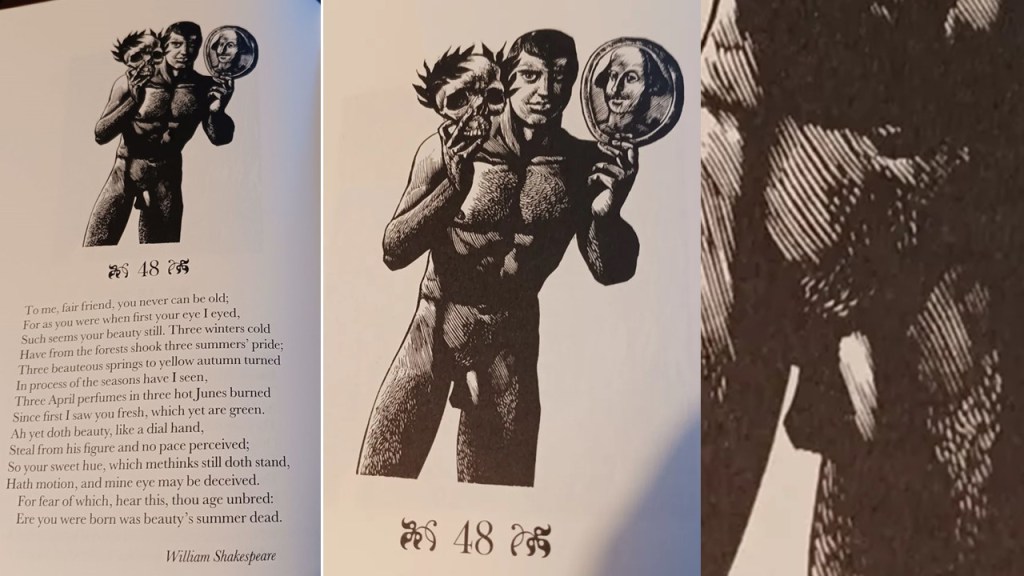

This sonnet drew from Peter one of the most intriguing illustrations, originally placed in his Folio edition of The sonnets) I have ever seen in which a lithe naked young man stands holding in each upraised hand a skull with a poet’s laurel wreath round its bony brow and a picture of a middle-aged balding Shakespeare in the other. The young man looks more of the twentieth-century than of the English Renaissance and, rather than look as though weighed down by time, playfully reminds Shakespeare that he is the one more near death than he and that he is masking what he wants from the young man with pictures of his own possible awaited options for a destiny. In one hand, that destiny is the honoured immortality of a dead poet or, on the other, a man whom in age is neither beautiful nor extraordinary looking. But both options stand at only face-level, because the young man has challenged Forster as a wood engraver to create full frontal naked embodiment in him.

He does this with tonal effects of variably spaced carved lines that allow the illusion of density and volume to highlights of the man’s external anatomy and to what causes each artist to sexually desire young men, and this one in particular. Light and dark thrust into prominence, for instance, a very plastic penis bathed in the illusion of light – how simply a wood engraver achieves this illusion is clear in the detail. He is a cheeky soul this young man, his eyes say: Shakespeare: this thou art (balding middle-aged man), this thou aspire to be be (immortalized in laurels at your death) but as for now – you want me. To which Shakespeare answers – with the slight threat great poetry achieves:

Ah, yet doth beauty, like a dial-hand,

Steal from his figure, and no pace perceived;

So your sweet hue, which methinks still doth stand,

Hath motion, and mine eye may be deceived:

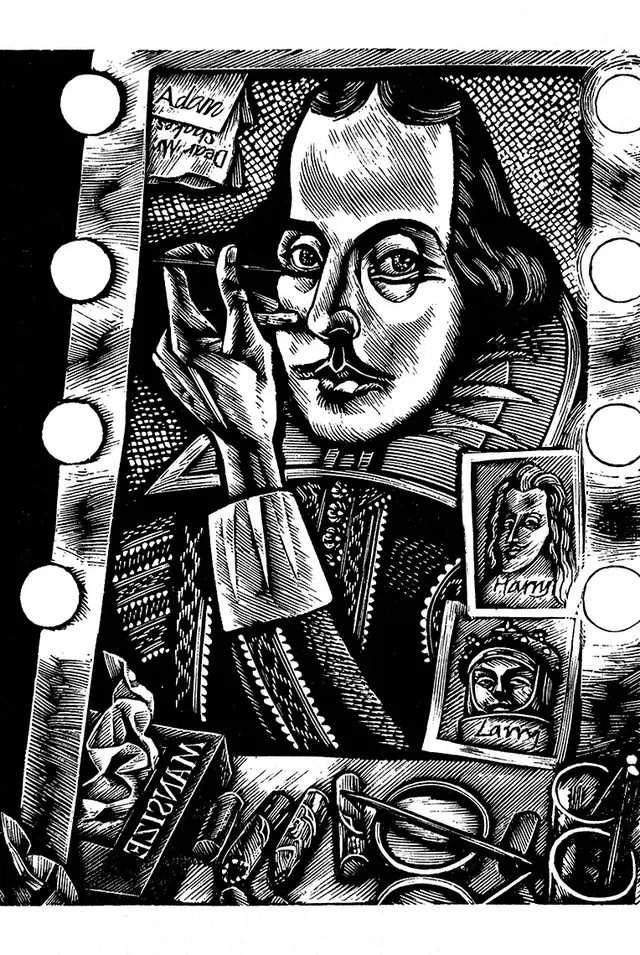

What makes sure ‘you never can be old’ he is asserting is precisely the cleverness and beauty of my art which makes things stand still – at least in the material of his art. Peter Forster in this picture is asserting the same for an excellent wood-engraver – though any Shakespeare-like pun on wood and stand has been foregone. Forster clearly thought Shakespeare’s poetic effects that of a diva-cum-actor, as in his Frontispiece to the Folio Sonnets, where Shakespeare sits at a dressing room mirror in a modern, for those days, theatre – surrounding by much lusted for signs of gratitude from acknowledged greats – making himself up – in more than one way. Larry must refer to Lawrence Olivier, and his bisexual reputation, the preference for ‘Mansize’, if any tissue is to be used another reference to Shakespeare’s ubiquitous cock-jokes.

Where does the revival of art and the love and befriending of young men come from. In 1979 Peter was 6 years into a relation with Hugh White. White’s obituary of Forster says they first met in 1973, becoming civil partners in 2006. The obituary picks out that Peter never changed, claiming that though a ‘shy’ man, Peter made friends easily, citing 2007 when he made a new friend – biochemical engineer Pedro Lebre now at the university of Pretoria, – who became important to both older men says Hugh wistfully. Hail Pedro, whose academic publications are now legion:

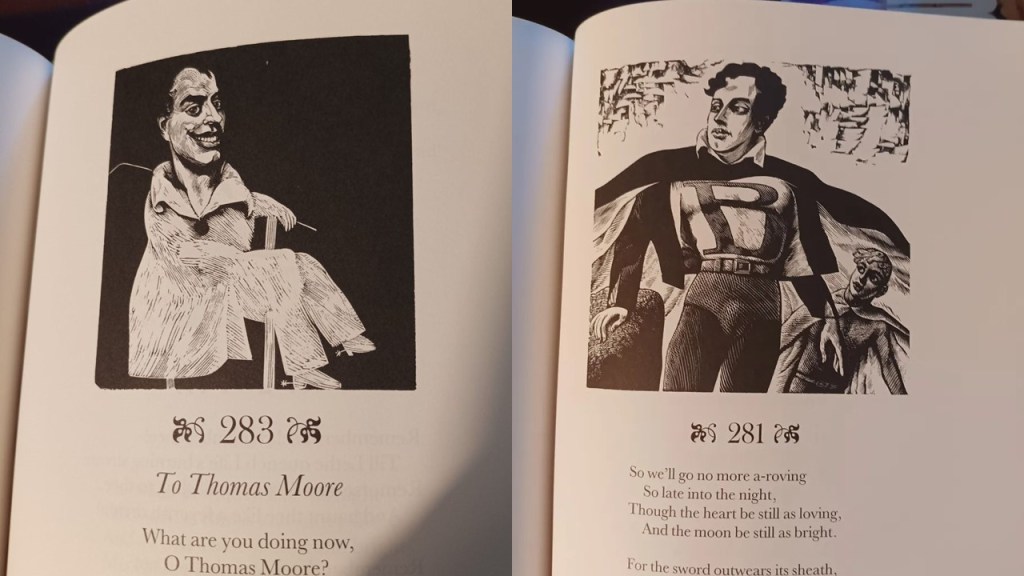

Forster’s illustration are used elsewhere in the anthology – not least those taken from the illustrations he did for Wuthering Heights, which he loved like Shakespeare, and which are used to illustrate her powerful poetry in this book. But I pick out two queer examples because they allowed Peter his flight of humour. Byron is still not thought of as a queer poet, though we know when he died fighting for Greek independence in Missolonghi, his last love was a beautiful Greek young man, and that bisexuality defined this poet of huge sexual appetite – in myth, that he encouraged, and perhaps in reality. Peter’s illustration of Byron’s poem to the infamous Tommy Moore, Irish poet and biographer of Byron, conflates George with another Irish poet Oscar Wilde, who Forster illustrated (again for a Folio edition) with access to the manuscripts offered to him by his friend, the poet’s grandson, Merlin Holland.

But my favourite in-the-ironic-know-about-Byron as a superlover is the illustration above to So, we’ll go no more a-roving, a louch queer male ‘cruising’ poem if there ever was one:

So, we'll go no more a roving

So late into the night,

Though the heart be still as loving,

And the moon be still as bright.

For the sword outwears its sheath,

And the soul wears out the breast,

And the heart must pause to breathe,

And love itself have rest.

Though the night was made for loving,

And the day returns too soon,

Yet we'll go no more a roving

By the light of the moon.

Well, George, his friends must have said – ‘the sword outwears its sheath’ – you can”t get away with that, dearie!’. Forster transposes Byron in the hero Batman, to utilise the B for Byron, with a clear intention for the night and a bulge in his tights. Robin looks on in pure adoration at his gay hero.

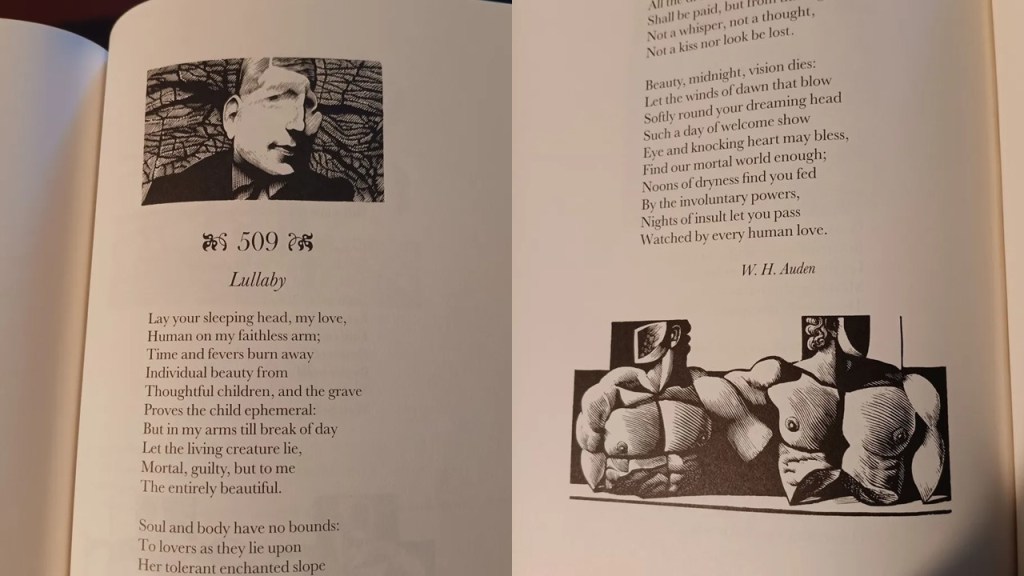

The last poem I want to pick out is one not in Palgrave, Auden’s Lullaby, written for and to his queer friend-in-arms-and-pen, Christopher Isherwood. For a portrait Forster draws the young man, Auden, set against the background of Auden’s cragged older face which the poet himself likened to the cracked and faulted features of limestone into which the young man seems to be sinking. However, the most beautiful illustration is the tailpiece to the poem, of two broken torsos – perhaps of stone because of the inner fissuring and fragmentary but altogether ‘meaty’ too. Eveything is incomplete in the depicted relationship. If the man on the left’s arm was not broken like that of most Greek statuary where would it be tending – necessarily to something absent because of time’s wear. The faces are like picasso masks but they look away each from the other, This piece is as tragic as the poem’s celebration of loving for the present moment, for that is all we have:

Time and fevers burn away

Individual beauty from

Thouhtful children, ...

For a tailpiece, it has the grandeur of the poem, if not the assertive hope that stands against homophobia in the name of a different kind of love:

Nights of insult let you pass

Watched by every human love.

This blog is intended as no more than a filler but the tribute to {Peter is genuine.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx