The First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays could be termed to give an authoritative statement of Shakespeare’s Plays. It does not. We think of authoritative things as things that can’t change. They do and must and authoring statements does not guarantee their infinite extension into wisdom that all must take on as belief. This is the lesson the Durham First Folio (each copy of that book had its own unique markers) tells us: Draw the moral though for yourself.

If Shakespeare were a book, what book would he be? And what would be the authority of that book to stay as it is unchanged in its rightness? On celebrating the stolen First Folio now returned to Durham University. A record of a visit to the exhibition Shakespeare Recovered at the Cosin’s Library, Palace Green, Durham on 25th June 2025 at 2.15 p.m..

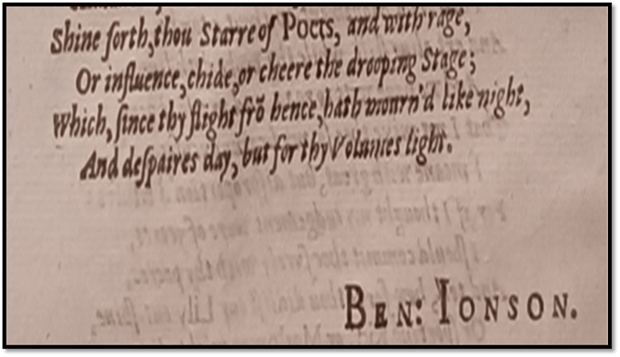

This and the exhibition it is about is the story of a book. Why tell it, however? Let’s start with an extract from the prefatory material from the First Folio – the end of Ben Jonson’s paean to his contemporary.

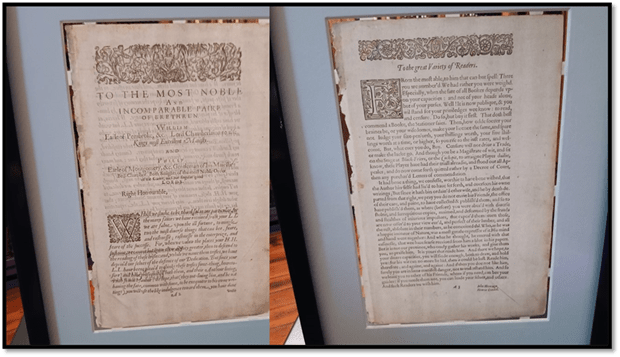

The extract from the end of Ben Jonson’s poem above is a detail from the page torn and damaged from the 1623 First Folio edition of Shakespeare’s then known ‘complete’ plays. The poem To the Memory of My Beloved the Author, Mr. William Shakespeare appears as prefatory material to the edition and must have been commissioned by its editors John Heminges and Henry Condell.

The poem plays upon the wonder of a poet honoured by such a weighty tome – which is why Jonson ends his poem with the near oxymoron ‘volume’s light’ (not a full oxymoron since Jonson knew volume in an object does not guarantee a weight relative to it). It is as if he were pointing out that significantly heavy things can also, in a comedian of Shakespeare’s stature – equal to that of Shakespeare as a tragedian too – can be ‘light’ in tone. And more importantly a preserved volume that is understood to be a book can shed the light of knowledge (and, had he been Matthew Arnold, he might had added culture ( or ‘sweetness and light’)) on the mysteries of human passion.

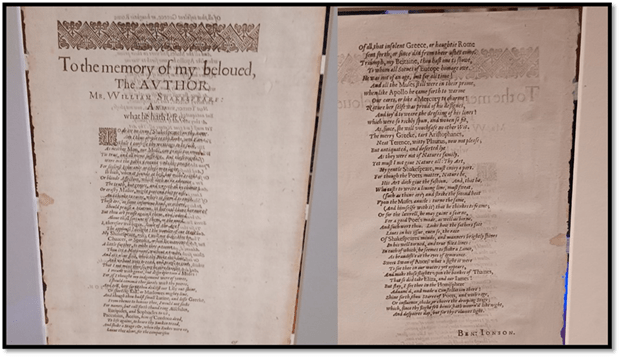

The whole poem in the exhibited damaged and detached pages from the Durham First Folio

Jonson played with the idea of the relative magnitude of poets who could be thought contemporary rivals, though no one knows his Sejanus as well as Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, nor his Volpone as well as Twelfth Night. Famous as I am , Jonson says, I hesitate to compare myself in size to him, as he plays with the witty idea of how big the First Folio is, as if cognate with the size of a verse dramatist’s ‘fame’.

To draw no envy, Shakespeare, on thy name, Am I thus ample to thy book and fame;

There is no doubt in truth that Johnson had ample name and fame, though no volume of his complete dramatic works would compete with the First Folio in his first lines, to return to ‘witty’ size comparison’s at the end of hispaean. By then he is using the term ‘star’ of Shakespeare in ways that is not far from its modern sense of being a great celebrity. His function is to show that the stage since his day has declined, and that almost as if it were mourning its lost ‘star’:

Shine forth, thou star of poets, and with rage Or influence, chide or cheer the drooping stage; Which, since thy flight from hence, hath mourn'd like night, And despairs day, but for thy volume's light.

We cannot over-estimate the importance of the First Folio, in that it is the only source of some of the plays attributed to Shakespeare, it also established a ‘canon’ (a list of plays authorised to be by Shakespeare and excluding ones that were more doubtful). Modern editions, however, tend to also use other sources of plays where they exist – sometimes even varying the readings from different texts.

When I studied Shakespeare at University College London, the course was led by the meticulous Winifred Nowottny, a master of textual variants and the rationales that might underlie a preferred reading (it was rumoured by Dr Keith Walker that though commissioned to produce the Arden edition of Shakespeare’s Sonnets the publishers ran scared when the textual notes grew so much that often there was only one line of a sonnet printed above them). We had a six hour paper on Shakespeare in which the Section A tasks involved parsing a given text of Shakespeare by discussing variants to the text that had to be remembered by the candidate without being able to see them. I seem to remember that I refused to do this and got punished appropriately – objecting to the fact that so much of that exercise depended on rote learning.

But the issues WERE important. See for instance the most famous speech from Hamlet, as it occurs in the first three different versions in the main extant sources. The Quartos were smaller published volumes of the plays, possibly as acted and transcribed and some of doubtful authenticity for any number of reasons – hence the term ‘Bad Quarto’.

For some the First Folio was the true authority for all plays, despite the fact that had all its readings been maintained, we could never have had the moment when Mistress Quickly reports, in Henry V, the death of Falstaff, the fat knight describing him as having ‘babbled o’ green fields’ (a truly beautiful phrase but in fact supplied by an eighteenth century editor of the play [Theobald]). Instead, we would have Mistress Quickly reporting that Falstaff died with the words ‘a Table of Green fields’ in description. You can see at least there why the authority of the First Folio was sometimes (rightly) questioned. But none of that detracts from its significance as a volume – for in Shakespeare size may not matter as much as we, or Ben Jonson, think it does in determining authority.

The Durham copy was bought by Bishop John Cosin, the Bishop of Durham from 1660 – to 1673, and a former academic and chancellor for a time at Cambridge University. His wish to own a copy of the 1623 volume reflects the new evaluations of Shakeaspeare at the period. Cosin was not only concerned to revive the see at Durham and the Chapel at Auckland Castle but to raise the academic viability of the teaching at his county capital. He established the Cosin Library on Palace Green.

As a student at Durham twice: once for a Postgraduate Certificate in Education, and afterwards for a joint Masters with a professional Diploma in Social Work. On neither course did I ever think of visiting this library, but once restored and by then retired I did see it after its restoration. It impresses with a dignity that belies its rather small size. So visiting this exhibition is in part a chance to breathe again its antique air – restored to a kind of freshness. In my collage below you see some of the persons on the guided tour I was on as well as the guide. You have to remember that the Durham First Folio was stolen at an exhibition in which it featured. Though charming in themselves the arrangements for visiting reflect that threat.

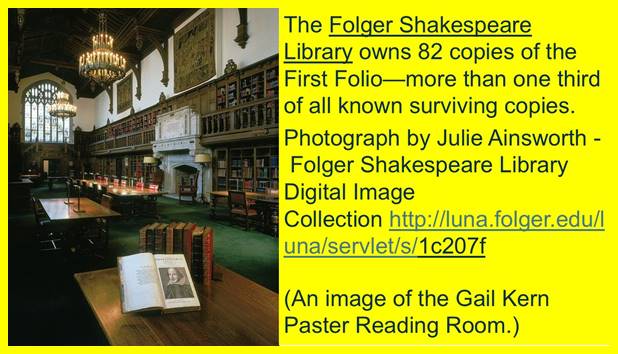

But I get ahead of myself for the purpose of the exhibition is not only to contextualise the First Folio but to tell the story of Cosin’s copy of it, not least the story of it being stolen, disappearing onto the black market during which it was dismembered in part, partly damaged – its binding systematically destroyed – and turning up some years later (10 exactly) in the Folger Shakespeare Library in the USA, who own the majority of surviving copies of the First Folio:

In fact there are two ways in which this exhibition is about recovery:

- It tells the story of the recovery of the book as an object and why that mattered to Durham academics, curators and bookbinders.

- It tells the story of how a stressed volume recovers its significance and whether that requires it to recover its appearance as it was before being damaged. This if anything is the main issue.

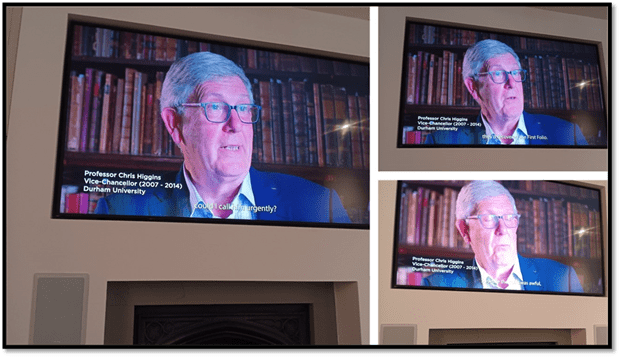

The first story is told in a small ante-room to the library proper by film featuring curators and academics – in the collage below where much of the story is told, in expressive facial gestures as well as words by the University’s Vice-Chancellor, Professor Chris Higgins.

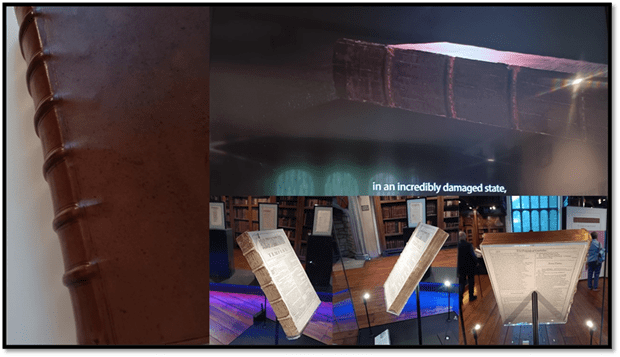

The star of the film though is the book. In the college below, it is described as having been found in an ‘incredibly damaged state’. In fact more details are supplied in a second film shown on a loop in the library itself. The book had lost its covers, the spine been damaged down to the removal of the threads that hold the binding to the spine of the book which bears the pressure of page openings. All the prefatory pages had been removed and their link to the spine broken.

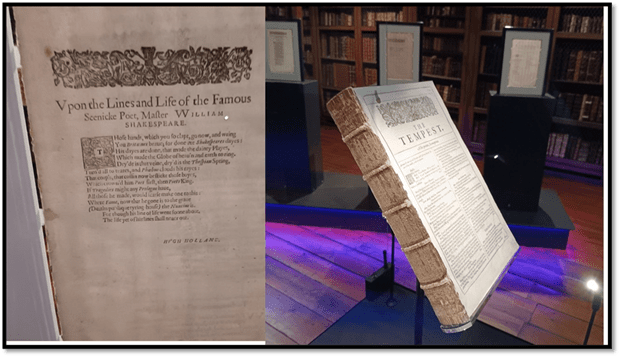

The collage shows on the left a bound facsimile copy of the book with the threads as they would have been seen in the original book, in regularly spaced strips across the spine and still protruding on the cover as they are seen no more, diving down into their role of maintaining the integrity of all of the book as a series of sequenced pages. But as the three bottom photographs, what we see on show in the library is a book only partly restored – its prefatory pages remain detached – the stress of their removal still seeable on the edge that was once bound to the spine, although what remains of the whole book stands in a vitrine with its threads restored at the spine, but not covered by the pages starting from the first page of the printing of The Tempest and ending with a page from Cymbeline.

Much of the material of the exhibition of why a full restoration was not attempted and one digital exhibit invites the visitor to try out a quiz like exercise going through the decisions facing the original conservatory restorers, where it is clear that any decision has costs or downsides as well as advantages. For instance to restore the book to a state that would look as it once did would damage the evidence of the nature of the book found in its fragments, whilst never really being the original book and hiding some of the interest and mystery of the bookbinder’s art. Exhibits even look at how the gilded edges of the book were created (not as pure gold at all as you might think, and telling the story with apt misapplications (but interesting and amusing ones, from Shakespeare’s words – the latter topic dealt with by Portia’s quizzical line about the caskets that hold the key to marriage to her: “All that glisters is not gold”. The whole story of the book told even better by the line: “Let me be that I am, and seek not to alter me’. It is used as a justification of the conservators to leave some things in the damaged book alone and as they are currently.

The latter quotation is from Act 1 Scene 3 of Much Ado About Nothing but is really about the self-justification of a semi-villain, Don John:

DON JOHN I had rather be a canker in a hedge than a 25 rose in his grace, and it better fits my blood to be disdained of all than to fashion a carriage to rob love from any. In this, though I cannot be said to be a flattering honest man, it must not be denied but I am a plain-dealing villain. I am trusted with a 30 muzzle and enfranchised with a clog; therefore I have decreed not to sing in my cage. If I had my mouth, I would bite; if I had my liberty, I would do my liking. In the meantime, let me be that I am, and seek not to alter me.

Don John is defiant in preferring the role of a ‘canker’ not a ‘rose’ and that alone is taken to be the voice of Durham’s First folio – I want to show, it says, how and why I am as I am now, and not as I might rather be in some ideal dream.

The detached pages thence displayed so that each side can be seen through the glass of their mounting, exhibit the dry tears of their removal or accidental detachment. In a manner, this is most moving, as Don John’s situation is not meant to be. The latter is a statement of existential being, not unlike those of Edmund in King Lear.

Meanwhile the semi-restored remnant of the book has a pristine beauty.

I do recommend seeing this exhibition. We (Geoff and I) enjoyed it.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxx

One thought on “Authority is a passing thing: The Story of one copy of the First Folio and an exhibition of its story in Durham”