As always with WordPress prompts there seems to be an agenda based on how a word is used in the immediate present of culture. After all only that could explain being asked for ‘your definition’ of a word, as if any words were amenable to purely personal definition and its use by that person validated only by a personal lexicon.

I suspect though that each personal ‘definition’ really applies to a relatively recent common usage of the term to indicate anything related to the experience of love with or of another: as if we were being asked what would your expectations of a ‘romantic’ date with a lover would be, or what would make a lover either be, or seem, ‘romantic’. The qualification I used in my last sentence, that we can ‘seem’ romantic when we are not, is there because our expectations are necessarily performative – based on how a person acts.

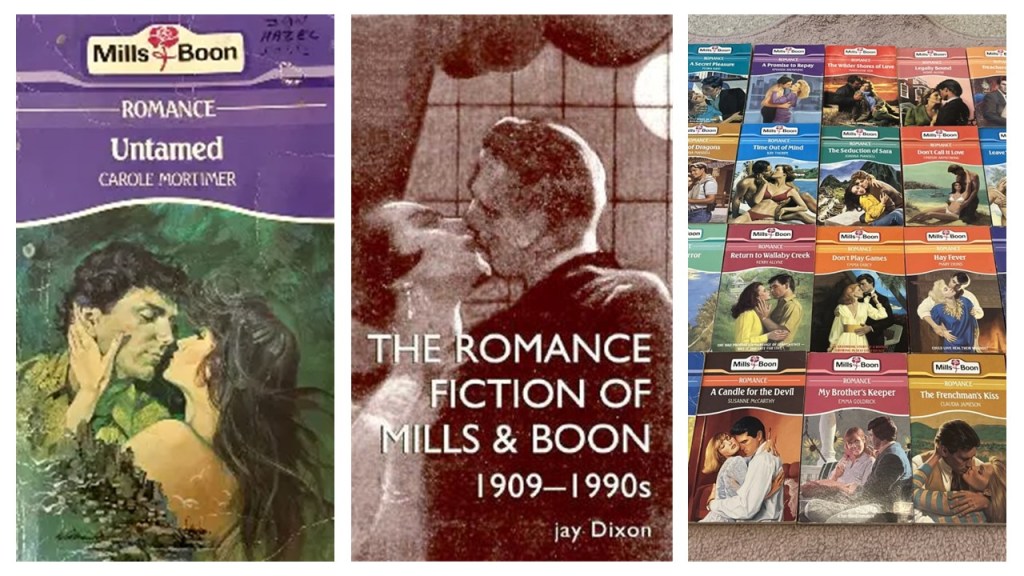

The dilemma of the ‘romantic’ is that what seems romantic in behaviour can prove to be entirely unreal and enacted without substance or authentic feeling supporting it. There would be no Mills and Boon novels without this understanding and no possibility of Jane Austen being considered a great realist novelistic, and not only in Persuasion.

But I don’t think therefore we need leave behind the history of the word’s usages, for in many ways they all depend on notions of what is authentic in a person and what is not – and from nearly the beginning of the history of the noun ‘romance’, if not the adjective ‘romantic’, was about the moral validity of any enactment of loving behaviour was based on the truth underlying a show.

Let’s take a fairly simplistic example of the etymology of the word, ‘romance’ from a useful webpage:

Medieval romance appears in England in a time period (1066-1485, from Anglo-Saxon rule to Norman Feudalism) in which a massive cultural shift was occurring, two languages affected the Anglo-Saxon tongue: Latin – the language of the clergy and the law – and French – the language of the upper class.

The word romance originates from the French word romanz. It defined works written in languages deriving from Latin. It indicated verse narrative in a vernacular language (from Latin “romanice scribere” to write in a Romance language, a language derived from Latin).

Then the word romanz was applied to works written in a vernacular language in general. Later it evolved to signify works telling stories about love and chivalry.

From a word characterising the function of a particular language when it formed one of a repertoire of languages used in a culture, it became attached to an ideal of idealised behaviour – that of the court in particular and generated lots of assumptions about the nature of works in that language: from the assumptions made about love in the court (known in literature as ‘courtly love’ and associated with love experienced outside other forms of social validation like family and marriage) as well as the moral function of the court regarding loyalty to God, the King, the State and to a notion of ideal behaviour that it is difficult to maintain. In looking at the etymology of the adjective ‘romantic’ etymonline.com makes two crucial distinctions in describing usage:

1650s, “of the nature of a literary romance, partaking of the heroic or marvelous,” from French romantique “pertaining to romance,” from romant “a romance,” an oblique case or variant of Old French romanz “verse narrative” (see romance (n.)).

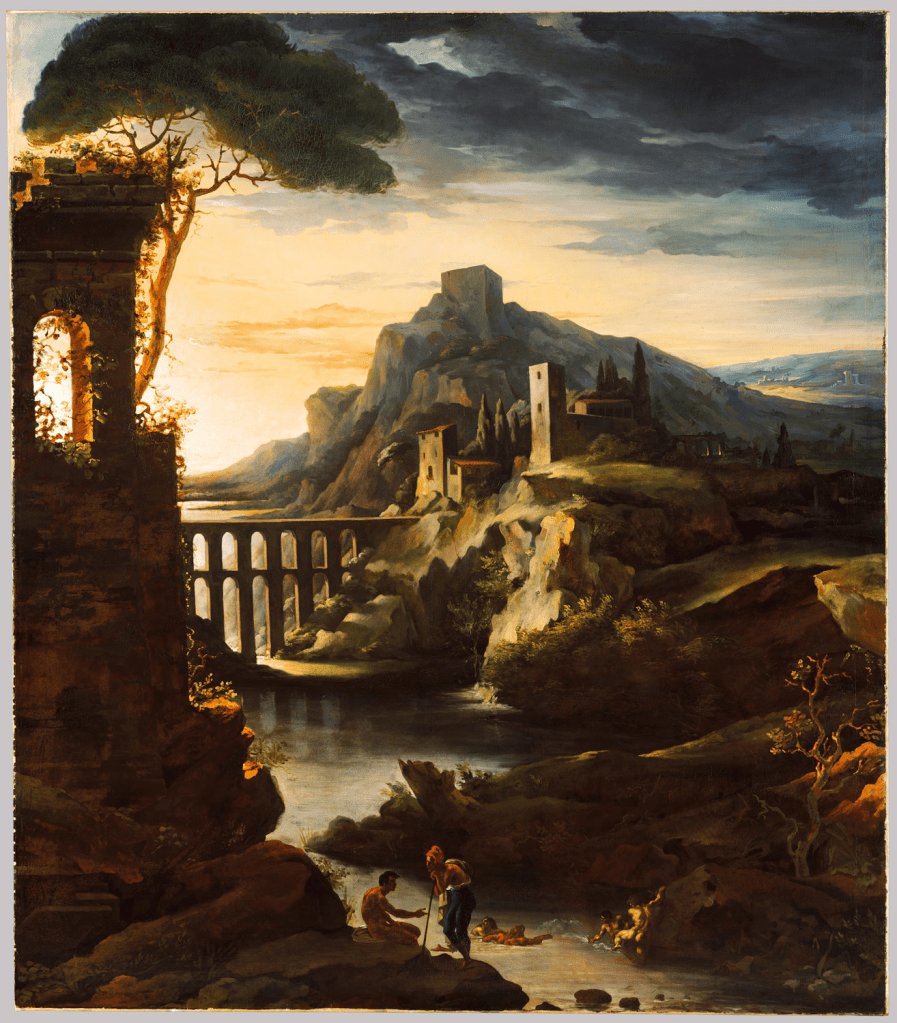

Of places, “characterized by poetic or inspiring scenery,” by 1705. As a literary style, opposed to classical (q.v.) since before 1812; it was used of schools of poetry in Germany (late 18c.) and later France. In music, “characterized by expression of feeling more than formal methods of composition,” from 1885.

The meaning “characteristic of an ideal love affair” (such as usually formed the subject of literary romances) is from 1660s. The meaning “having a love affair as a theme” is from 1960.

The first is the distinction from the used of the word from the eighteenth century and especially from nearer the end of that century when associated with the aesthetic movement in Germany, and then across Europe, usually called Romanticism in contrast to what became known as its binary contract in aesthetic terms, Classicism, although there was nuance in the contrast even then.

The second is from a word naming a ‘subject’ of ‘literary romances’ (I would say this should read ‘one of the subjects‘, especially of medieval and Renaissance literary romances) to meaning the name of the characteristics of a love affair , where what is ‘romantic’ is considered a variable based on personal choices and prescribed personal characteristics. The latter is I think where this WordPrompt question is coming from.

Wikipedia gives more detail about how the medieval romance increasingly distinguished itself from being solely about fantastic tales of masculine heroism and self-testing.

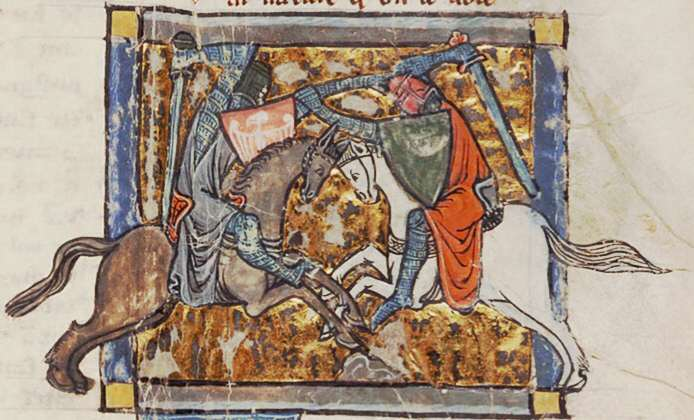

As a literary genre, the chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that was popular in the noble courts of high medieval and early modern Europe. They were fantastic stories about marvel-filled adventures, often of a chivalric knight-errant portrayed as having heroic qualities, who goes on a quest. It developed further from the epics as time went on; in particular, “the emphasis on love and courtly manners distinguishes it from the chanson de geste and other kinds of epic, in which masculine military heroism predominates.”

Not only is this the case, but Spenser in The Faerie Queene sought to complicate things further in terms of sex/gender definitions of romance, possibly in obeisance to his own Faerie Queene, Elizabeth I. His most telling knight is Britomart, a cross-dressing female, but his male knights too have to prove their passive as well as active ‘virtues’. Nevertheless, the idea of what makes a man ideal underlies the genre even in its continuing history, although Tennyson also plays games with sex/gender, including all the then available definitions of ‘romantic’, in his Idylls of the King, as suggested also by the Wikipedia entry on the poem:

Tennyson sought to encapsulate the past and the present in the Idylls. Arthur in the story is often seen as an embodiment of Victorian ideals; he is said to be “ideal manhood closed in real man” and the “stainless gentleman“. Arthur often has unrealistic expectations for the Knights of the Round Table and for Camelot itself, and despite his best efforts he is unable to uphold the Victorian ideal in his Camelot. Idylls also contains explicit references to Gothic interiors, Romantic appreciations of nature, and anxiety over gender role reversals—all pointing to the work as a specifically Victorian one.

Yet romantic love novels of the twentieth-century also involve testing – especially of romantic love objects but usually men by women. Modern romantic novels (I taught Mills and Boon novels as part of a Literature of Romantic Love course when I taught at Roehampton Institute) often deal with what constitutes a ‘romantic man – particularly what combination of the ‘hard’ and the ‘soft’, the ‘tame’ and the ‘wild’ or the powerful and vulnerable should be combined in such characters (and indeed these same issues arise in Jane Austen and the Brontes as well as Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca). In Rebecca and Jane Eyre the romantic hero has to have his power-base destroyed (and lose his sight in Jane Eyre) before he is good enough for the heroine, the focus of the narratives.

And let’s be honest the issue in queer novels. I am currently reading Curtis Garner’s Isaac and it is there too in the expectations of a boy growing into his queerness. Most of the novel deals (I haven’t finished it yet and will blog properly when I have) with meeting an older guy, Harrison. When standing down a group of men presenting as macho heteronormative, Isaac thinks that: ‘Harrison wasn’t afraid of anything. he would change the world, …’.

However, this powerful, hard man is not enough. Isaac wants to see, and does, ‘a flicker of his uninhibited kindness and sweetness’. He would be a hard man capable of giving ‘him tenderness’. (1) The best novel to examine this takes on the modern meanings of the ‘romantic’ head on. It is at its best in Robert Jones Jr. (2021) ‘The Prophets’ (a very under-recognised novel about which I blogged here in a way relevant to my present theme) but in the context of slavery, racism and violence).

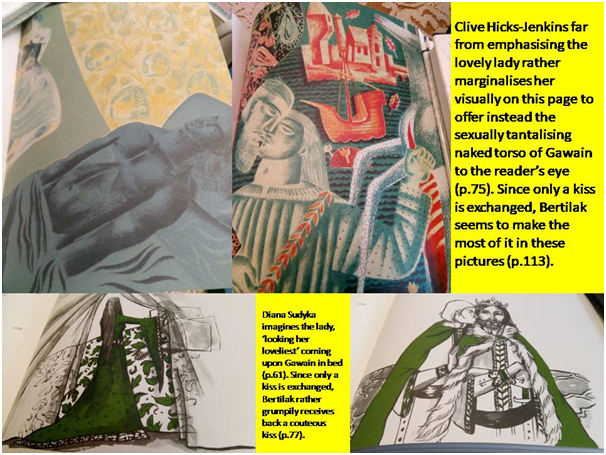

The point of all this is that, for me, the meaning of ‘romantic’ is really about the making of stories – fabulation and confabulation (the latter being a supplement to failing memories – it is a contested notion in mental health and I wrote an assignment on it for a course on mental health led by the wonderful Mark Solms [see at this link]). To be romantic is to be a person – for me a man or non-binary identifying person – who is someone who can be open – but not passive – to reconstruction by multiple stories and being themselves willing to be subjected to multiple stories. This is not so far from the motives that generated Sir Gawain and the Green Knight as a medieval romance. I played with the queer potential in this poem in an earlier blog about the recent film of the poem the poem itself, and its illustrators. Here is a collage from the blog at this link:

All for now

Love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

______________________________

(1) Curtis Garner (2025: 141f.) Isaac 141f. Harpenden, Verve Books.

One thought on “Literally fabulous or confabulated – the dream of romance”