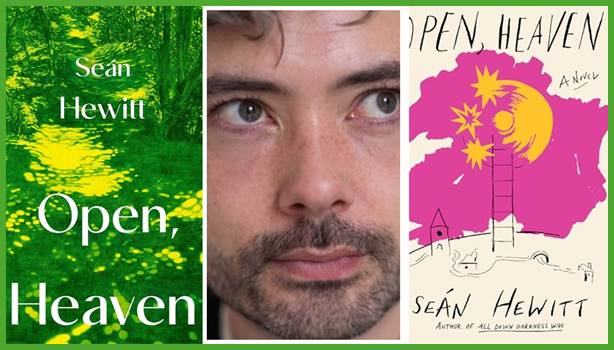

‘It was all unfinished and most likely it always would be’. Open, Heaven, which despite having many endings is also truly an unending story, asks us how much we really want our loves to remain open rather than closed to future promise: that ‘life of constant negotiation, movement, agony, bliss’ And we desire this perhaps even at the cost that ‘It was that that had undone me’. If the condition of the unfinished and unended is our only hope of the ‘promise of a different life’ maybe we do not want love to end our romantic quest. We want instead the situation where precisely because the object of desire remains unattainable , ‘the desire never stopped’ and because what has not been attained is also forever unattainable ‘the desire would never end’.[1] This is a reflective take on Seán Hewitt’s 2025 novel Open, Heaven New York, Alfred A. Knopf.

This blog is not even intended as a review as such but as a reflection on what this novel ought to have done to the paradigmatic models of queer fiction in an attempt to age them into the maturity of a literary tradition. Queer fiction after this need not be an attempt to promote positive images of either queer love or queer desire, nor satisfy such desires in either romantic or frankly sexual fictions of satisfaction. Hewitt is a novelist who never quite does anything that confined to norms – whether hetero- or homo-normative.

And reviews of Hewitt’s novel have tended to speak of this novel as a means of introducing a character with unique characteristics, James. The stress on characterisation also raises the question of the reliability of James as a narrator or as a man who has learned a thing or two about love or desire in the very story he is telling. Thus Conor Hanratty, writing for the national broadcaster RTÉ raises problems about the realism of the character only to resolve them in the manner in which that character subsists between the boy in the story, and the older man telling the story of himself as that boy:

James’ ability to understand and even sympathise with the characters around him, particularly his mother, are surprising in one so young, but Hewitt pulls this off, perhaps, by blurring the lines between past and present in the distance from which James tells his story.[2]

But I wonder how much of the power of Hewitt’s novel lies in the individuation of that character, as I will go on to say. Sarah Perry, a long time supporter of Hewitt’s self-projection as a novelist, shows that we must take the James constructed in Hewitt’s writing not only as a highly individuated, problematic and hence, unreliable, person, convincingly portrayed, but also as a kind of case-study that allows us to access universal truths about the operation of love, desire and memory (the stuff of poetry) in universal, if restrictedly human, terms.

Hewitt’s depiction of an enthralled and uncertain love is painfully convincing. James watches for signs his ardour is returned, and often thinks he sees them – “I imagined an ocean of thought, a hidden spring of love, and I thought … he would let me in.” His suffering is particular and universal. His gayness is never peripheral, and it makes his love for Luke perilous: “I could not imagine a time when I would not have to hide my desires,” he writes.[3]

In this formulation even the contingent fact of the social and political history of oppression against queer people becomes absorbed not only in the preference for self-absorbed secrecy in James as a character but also in the definition of love, desire and both individual personal identity and its construction in human social relationships. For me this strikes the right chord, although my interest in what follows will be more on how Hewitt contributes to debate about the universal issues, using queer lives as his starting point, than with matters related to the handling of characterisation and plot per se.

Sometimes I think Hewitt’s aim as a novelist and poet is to evade classification altogether by mode, genre or other classification entirely, just as does James does at moments. It is worth examining that evasion in James in the novel’s only open sex scene – a scene bound by many barriers to, and enclosures forbidding, anything but a very closed (or closet) mutuality. The boy Luke, who James desires, clearly embraces completely, without wanting to say so (since he has, in James’ judgement, ‘no language for his desires’), the normative expectation and promise of the end-role of a heteronormative male (a dad like his own). Hence, James can only become ‘completed’ in his specifically genital sexual desire with Luke in mutual orgasm by becoming for him ‘whoever he wanted’. In a negotiation with Luke between their mutually self-stimulated bodies and their imaginations, the real body of James must never be allowed to be touched nor touchable by Luke. James may be to Luke, lying together both in separate sleeping bags and in this borderline state between real bodies and their imagined metamorphoses, wearing ‘whatever mask he gave me’, ‘Mia’s imagined body’ in order to allow Luke to masturbate without compromise to his imagined identity with heterosexual desire. James can ‘become’ his female sexual rival Mia Gallager in Luke’s (and perhaps his own) imagination because he has access of ‘womanly’ knowledge only afforded to him by his girl-friends, including Mia, because girls find his own sexuality unthreatening. However, even while he performs Mia in sex talk for Luke, there remains a chance that, unbeknownst to Luke, it was precisely the ‘strangeness (that) excited; Luke of the queer metamorphoses that occur in the dark tent in which they both closely lie together, without , touching each other physically. In such a situation the notion of from whom the ‘touch of a hand’ is emanating becomes itself estranged from strict evidence of reality. Merely imagining himself as Mia Gallagher is powerful enough to excite Luke and allows James ‘everything I could imagine, the dream and the real thing in one’.[4]

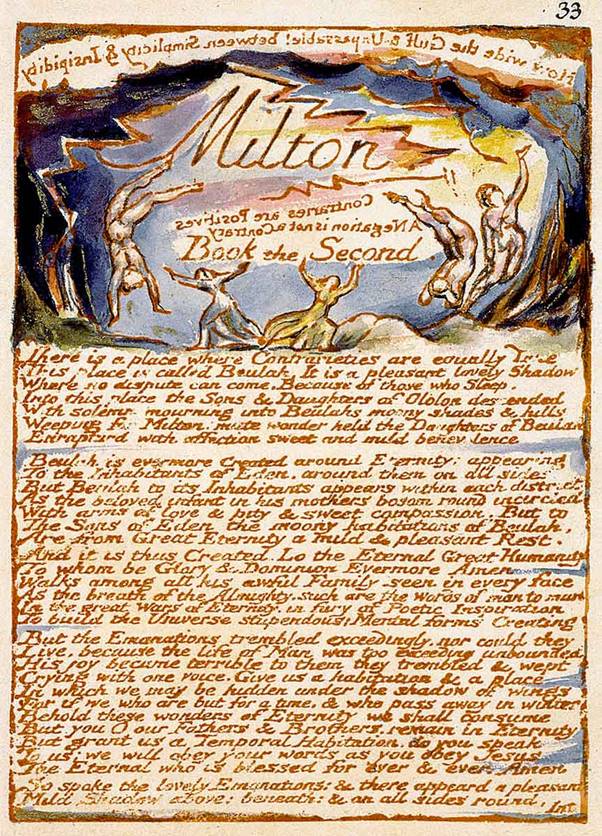

I can’t now read this novel only as a novel – and perhaps that is a spoiler for me – without it also becoming for me a philosophical enquiry into the way we know things, even bodies and our means of feeling that we ‘touch’ them, that opens up debates on the nature of love and desire and their relationship that we thought long close. Love and desire might for instance interact not only as companionate experiences but also be antagonistic to each other. The novel matters to me because its peculiar and particular felicity of insight is sought in repressed and partially closed queer relationships, forcing them to open up like a blossoming flower. Sarah Perry sees this in the use of the epigraph of the novel by Williiam Blake from Milton and the novel title derived therefrom:

It takes its title from William Blake’s poem Milton, which speaks of wandering through “realms of terror and mild moony lustre, in soft sexual delusions of varied beauty” – a line that quite nicely describes the reader’s experience of this book.[5]

To be fair Connor Hanratty sees that too, although he rather oversimplifies and forecloses what in Sarah Perry is subtly open to elucidation and philosophical extension.

… Open, Heaven begins with a quotation from William Blake’s Milton. It lists various flowers opening and awakening, while “men are sick in love”. In Blake’s poem, this springtime catalogue comes with Biblical lamentation, while the great poet Milton looks on. As a programmatic introduction, this could hardly be more precise; Hewitt has written a novel of sexual awakening, of the English countryside, of sadness, and of intensely poetic observation.[6]

I balk at the term ‘programmatic’. This is for me far from being about ‘sexual awakening’, unless by that process of opening we also include the way that hour humanity, as thrown into history, is often a history of closed-up and closeted sickness as well as health in that gladness of the morning. For my purposes this novel offers some response towards a solution of such debates. However, if it does so, If so I am in danger of losing a beautiful romantic novel whilst gaining a model of queer epistemology of the world of romantic love and sexual desire, proximity and distance, being held (or staying) or let free (or leaving), and the role of the body as agent and receptor of the meanings of all those states of being and/or imagination.

The novel certainly proposes such issues. The older narrator, James, who tells the broken stories of the novel across distances in their constitution recounts indirectly the words of his once husband that ‘he had realised that I could love him but not desire him’. The novel opens up distance between love and desire here that demand articulation of the difference perceived between these states.[7] More telling still is the continual interplay in the novel between what it means to be ‘close’ or ‘distant’, emotionally, cognitively or physically – for this distinction too demands an understanding of the relationship pf bodily sensation and its imagination at relative distance or through barriers of defence (even such as are separate sleeping bags). And amidst all these questions remains the notion of touch related to strokes of pleasurable connection and the piercing awareness on skin of the application of violence productive of pain.

And for me, this makes this novel the better for it is a truer representation of growing up queer than others that demand that binaries remain binaries – especially those of the open or closed nature of things in general – which imagined the defeat of repression as a new openness, or demand closure in novels. For me too, this openness explains a problem so key to me in this novel that is oft closed in others – the significance of James’ relationship to his brother Eddie and the clear connection of that to the unfinished nature of Eddie’s life-story. Luke is continually knocked back by the fact that James relationship to Eddie is no a sustaining one, and often compares James’ luck in having a complete family to his own apparent abandonment by both parents to whom he is a single child. And so often the relationship between James, Luke and Eddie is constructed a kind of triangle of unequal attachments, where Eddie is seen as superfluous (and a barrier) to the closeness as a couple that James wants to build with Luke.

The second time James sees Luke returning from an adventure with fireworks with a ‘cocky, defiant walk’ he becomes the ‘only thing in my mind’, associate with the play of triumphant new identities that mask James’s gloomy reserve:

… the vision of Luke’s face, like a bright mask, lit up in the dark field. A sudden apparition, revealed by a glowing flare, his eyes starry with fireworks. Even his hair seemed to blaze. I felt a pull towards him, …[8]

Though this signifies the destructive lyric (nay Apollonian and solar) proportions Luke takes on for James taking things in and ‘blazing them into its hot white centre’ – his desire is clearly for that object already apparently chosen for him by Eddie – a ‘guy’ that is made precisely from one of ‘James’ old jackets’ and thenceforth called ‘James’ by Eddie, as if it is he that, having identified his brother with a sacrificial object, allows James to then see that guy as it burns as a symbol of his furious desire and then project that identification – I refer here to the Kleinian concept of projective identification – it later (in the quotation above) into Luke:

The flames had torn their way through the sacking and rushed through the straw stuffing of his body. They were tearing out all over him, eating him up from the inside. The brighter the fire the more I seemed to light up. I was transfixed by it. It was like seeing all my desire made physical, like meeting God: …[9]

From that moment Eddie, James and Luke are locked into a triangular psycho-drama of need, desire and the evaluation by each of the other’s relative power as objects of compulsive need and attraction. The next time James meets Luke he ‘cannot take (his) eyes off him’. Gill, who is temporarily caring for Luke, insists that Luke take James out to see the turkeys in the barn, an opportunity for closeness that is disrupted when James’ mother urges that they :“Take Eddie, too”. And therein is born a clear triangle of exchanged looks of need:

Eddie stopped stroking barley and looked up at Luke and me when he heard his name. I was annoyed that we would not be alone.[10]

The triangle even begins to bother James and it is in this awareness, we see one of the ethical problems that knit, love, duty and desire in the novel, and remind me of my own infatuations as a queer boy (see the blog on it at this link). He says later of his closeness to Luke, as friends doing the things male friends do, where everything Luke proposes to do James says ‘yes’ to; to the point of creating almost a unity of their double body identity:

… I wanted to be lost in him, and the hope was a torture to me. I have memories of Luke and me fishing in the canal, the way the tan and freckles spread over his face and my forearms. Everything else disappeared in those hours.[11]

A feature of this prose is that it becomes increasingly difficult to see if Eddies is lost in Luke or in memories of Luke – a feature of the already double identity as a older narrator of a younger self. The thing that matters to him and us may not be his behaviour in the past but the effect of his past fascination with Luke on future memories of it in the long duration since the events happened, including those at the time he is narrating these events. Even at the level of memories the triangulation of need and desire between Eddie, James and Luke is to the disadvantage of the first named. Obsesses by Luke, he says three paragraphs later than the section quoted above that has so forgotten Eddie that he may not even be real – a figment of his retrospective imagination or an even younger self-image. More troubling is the way James tries to control the past and to manipulate its scenes and characters, as unreliable narrators oft do:

The thing that troubles me still about this is that I do not seem to remember anything about Eddie, only occasional glimpse; …. It is as though he has become a ghost in my mind, and I have spent years trying to piece it back together, looking at old photographs and videos so I might place him back onto the past.

And not remembering Eddie becomes even another way of thinking about the agency of imagined touch over a distance (here simply of time rather than space and/or variations in social behaviours about the expression of mutuality – allowable between brothers)as a means of controlling the unbearable nature of episodes ‘flooded with an awareness of endings, a long drawn-out goodbye’…’. Not that the ‘feel’ describe here is entirely a product of cognition, emotion and the bodily senses not just of the latter, like ‘the hand that can be clasped no more’ in Lyric VII of Tennyson’s In Memoriam:

When I feel Eddie’s hand around mine, or the press of his body falling asleep on me, or the feel of his soft hair, I cannot be sure that the memories are mine at all, and sometimes I worry that I have invented them, either to comfort myself, or to make the regret more real. There is a part of me that hates Luke for this, as if the reason that the memories are so partial, so fleeting, ….

Luke is to blame because he absorbs imagination in the recreation of sexual desire feeding into false and unrelated images of a future of being in love. Of course, this is grossly unfair but it raises the issue whether Luke isn’t any less fantasy creation than Eddie could be, as the Gothic elements of the novel signify– seeing faces in the dark, shadow of a barn door or fog as if some unreal threat represented not just by another but otherness in oneself – the doppelgänger (or Brocken spectre in Hogg’s Confessions of a Justified Sinner).[12] Even near the end of the novel James says: ‘I could think of nothing but Luke, and thinking of him pained me, because I knew I should be thinking of Eddie instead’.[13]

The reason he ‘should have been’ thinking of Eddie is because Eddies is here and earlier a ‘frail’ being in every sense, even ontologically. His fate is uncertain and no end is given to his story although his highly probable death following epileptic fit haunts the novel. In the beginning of the novel these fits are more in control than latterly but in some way only controlled by wishful, as well as anxious, feeling of those around him. But more than that he is a self-consciously ‘flat’ character (an obvious fictional character as it were) as E.M. Forster would have described him:

… he seemed in some ways like a pet, and in others somehow robotic. It was as if all of his movements were conscious and made with a determined effort to seem as human as possible. He was always being taken back and forth to the doctors, because he had fits sometimes when he was overtired and overwhelmed. It was nothing too serious, all under control, bur he was fragile, and we were careful around him.[14]

How much James cares for Eddie as part of that convenient ‘we’, especially when (as he sees it) under the thrall and pull of his desire for Luke like the pull of the bonfire round a guy – remains a necessarily open question. And again this is about not only triangulated competition for attention in the substantive story of the young people but competition for memory space – and consequently space in the writing. My favourite flower symbol (for it always edges on that) is the ‘forget-me-not’, for its very name bespeaks the theme of contest against either generalised or, more usually, specific and partial (in both senses of the word) forgetting.

The name of the flower is itself rooted in mythology, notably medieval German chivalric tales. A rather anodyne entirely none-medieval version of the myth (unlike some versions with knights drowning in their heavy suits of armour in quest of the flower on riverbanks) is told by Mary Catherine Judd in 1901:

THE FORGET-ME-NOT

German

There is a legend connected with the name of the little blue forget-me-not which everyone loves so much.

It is said that a boy and a girl were walking by a river that flows into the Rhine. The girl saw a lovely flower growing just by the water’s edge. The bank of the river was steep and the water swift.

“Oh, the beautiful flower!” she cried.

“I will get it for you,” said the boy. He sprang over the side of the steep bank and, catching hold of the shrubs and bushes, made his way to the place where the flower grew.

He tried to tear the plant from the earth with both hands, hoping to get it all for her who was watching him from the bank above.

The stem broke and, still clasping the flower, he fell backward into the rushing stream.

“Forget me not!” he cried to her as the waters bore him down to the falls below. She never did forget her blue-eyed friend who had lost his life trying to get her a flower.

“Forget me not!” she would say over and over until her friends called the little blue flower by this name.

Now these blossoms are called forget-me-nots all over the world. And whether this story is true or only a legend, the dear little flower could not have a prettier name.[15]

Forget-me-nots have two major roles in episodes in the novel and in fact become functional in its temporal structure – ending one sequence in the narrator’s supposed present and recurring after the long duration of his childhood life-story has been recollected and retold [16]. They appear at the end of the Prologue supposedly written about the year 2022 and they return with the resumption of that part of the story some 180 pages later, when the forget-me-nots might have been forgotten by some readers.

The ’forget-me-not’ is in this tale and in our novel closely and complexly related not only to memory and forgetting but to the claims made by the desirous about the nature of the love they give and expect, equating that (wrongly I expect) with the desire itself. In the novel they underlie ‘clouds of cow along the canal bank’ as a ‘bright-blur blanket’ that was ‘ruched in the dappled light’. That word ‘ruched’ has just about the right amount of reference to artifice, although based on a natural origin to describe tree bark, to alert us a very constructed symbolism enfolded in these forget-me-nots, such that we know the ‘road’ they lie on is also in time as well and space, such that the sentence ending ‘and further down the road they had started to go to seed’. In a page the tangle of forget me notes James picks are turned upside down and the ‘spent’ ones are subjected to James’ habitual behaviour with them, learned (he says) from his mother: ‘to take them, turn them, and shake the dried flowers to scatter the seeds’. Whether his mother’s lore of natural building on profusion or not this metaphor I think joins the many that refer to the shedding of seeds that make a man conscious that he has caught ‘his breath in his ‘throat’, as he did it. By the time, we see the ‘handful of forget-me-nots again’ they are laid carelessly on James dashboard as he drives away from whence they were shed. [17]

All this stems (if you can forgive the pun) from the obsessive interest in the manipulation of time in ways that can be both naturally and artificially regulated (even in the imagery of the spooling and unspooling of a film reel -like that In Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape in relation to audio tape reels – see my blog on that at this link) in human life – and our reading of James depends a lot on how we read James’s agency in this. Sarah Perry quotes the opening of the Prologue thus:

Time runs faster backwards. The years – long, arduous and uncertain when taken one by one – unspool quickly … the garden sends its snow upwards, into the sky, gathers back its fallen leaves, and blooms in reverse.[18]

And says of its prose:

The prose is worked at, just as a painting or concerto must be worked at – the imagery is fitted exquisitely to the mood, the structure designed to trouble the reader with the rapid fluidity of time, the events all plausible, but contained within the novel’s atmosphere.

In both his poetry and prose, Hewitt seems to me to be working, with immense fidelity and skill, towards a singular vision, in which profound sincerity of feeling – and the treatment of sexual desire as something close to sacred – is matched with an almost reckless beauty of expression. What is that, if not bravery?[19]

What is said here is precise and to the point but has more resonance in the meanings that available to be read in the novel – of James as a character and the ethical responsibilities implied in working with human memory than she here elucidates, unsurprisingly in a short and excellent review. We know the ethical element is there because forget-me-nots appear again precisely where forgetting seems an unethical act on James part fir he is at that moment saying that:

I didn’t know how to live anymore. I didn’t know how to choose between this delicate, innocent world and the future I was driving myself headlong into. I didn’t know which love I wanted mire: the love that consumed me, burned me, that fired my dreams and made me want to give myself up to it, or the love that held me, that had made for me this soft, beautiful cocoon.

You have to be aware here of all the metaphoric strands of the novel this pulls together – the reference to cars and driving in one or other direction, the burning of men (or ‘guys’) by fire to see the range of the ethical reference in James’ mind and feelings. And then what follows this is this exquisite passage of the handling of the dramatic and symbolic in fiction:[20]

The problem with time is that humans tend to deal with it in parcels, as according to Aristotle, art does – imagining it in chunks, each with a beginning, middle and end, whereas we want still to talk of our objectives that we place outside time, without beginning nor end (and hence no middle). The nearest we get to the latter is cyclical time – hence the importance to this novel of the cycle of seasons that militate against the linear sequentiality of stories, which makes forgetting inevitable and desirable. Poets have always talked of time thus – some very self-consciously, and Hewitt is no different. I myself see Tennyson standing large behind this work, though this isn’t dependent on Hewitt thinking so too (I suspect he is no fan of the Victorian greats outside of Gerard Manley Hopkins).

But he certainly uses the cycle of days like Tennyson, as he does the imagination of clasping a hand, probably from a common source in Greek lyric and narrative poetry. In Lyric 121 of In Memoriam, Tennyson sees love for the dead Arthur Henry Hallam made eternal in the embrace of the morning and evening star (in fact the same star);

Sweet Hesper-Phosphor, double name For what is one, the first, the last, Thou, like my present and my past, Thy place is changed; thou art the same.[21]

Of course Tennyson believed that identity may be continuous – even after death – and Hewitt does not, probably. Yet the patterning of morning and evening follows a similar metaphoric path, with the ending feeling like the shade of Tennyson’s power Tithonus, with a touch of Keats’ Endymion, about a man bound to time and ageing but nevertheless refreshed in the arms of the dawn. It becomes a passage dealing, as so much else with the issue of what it means to touch without actually physically touching:

The moon was just a thin, pale crescent in a pool of rosy pink, and the sun was on the rise. And I thought that, although the two could not be said to touch, there was still something between them, some radiance that spread from one to the other, as though, quite tenderly, the morning was holding the evening in its arms.[22]

When we hold something, we not only clasp it but course it stay with us and does not leave, as James feels Luke should not leave him, but in the case of this metaphor the act of ‘holding’ is a momentary, if repeated thing, in the continual act of things and persons leaving each other behind. And this is why this novel examines desire through the act of imagined touching, where love and desire seem complete in each other though this need not be the case. It is one of the reasons I believe that James so despairs at the use by Luke when he leaves him of that awful and casual phrase people use with each other about ‘keeping in touch’. [23] Touch in reality, for him, is a visceral thing for James, felt best when you hold in your hard sharp things that can cause you pain like nails or tent-pegs.

Touch is something James learns that he must refrain from in relation to other boys, as he does first with Etienne when he stays with him and his parents in France on a foreign exchange. When James catches sight from behind him, of Etienne masturbating, he learns that: ‘There he was, and here I was, and matter what I wanted, no matter what I dreamt of, I could not breach the distance. … I could not make myself move towards him’.[24] Breach the distance is what touching is and distances of all kinds keep people apart – space, time, fear or social convention for instance. At points before they reach some understanding, James dears that he is kept apart from Luke ‘for some infraction, some intolerable proximity I had forced on Luke’. [25] Yet again closeness – especially the closeness of a touch is the acme of all intolerable proximities.[26]

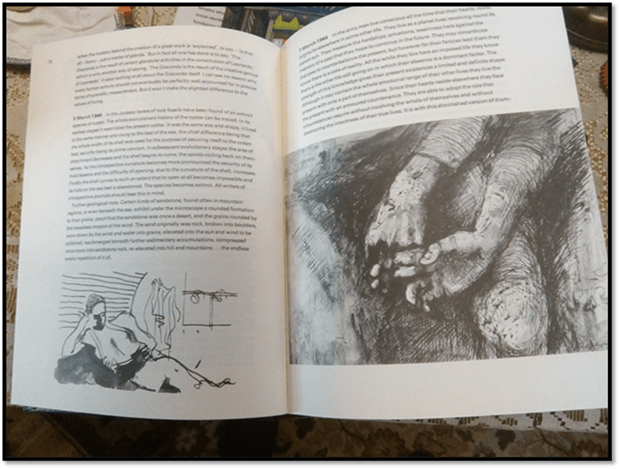

Keith Vaughan (1950: 78f.) Journals and Drawings

Sometimes, James tries to understand his distance from Luke by thinking him open to James’ adoration, which to some extent he is, because he takes the distance from his viewer that an aesthetic object does: ‘a statue of beauty …, considered and beautifully made’. Ar other times he thinks the distance is inscribed in prescribed gender roles that describe how men must relate to each other, through common sharing of heterosexual pornography, for instance. It is the only means of addressing sexual desire that they otherwise fail to understand:

Men only spoke about these things with each other because they were afraid not afraid of each other, or they knew there was a boundary between them that neither wanted to cross. I did not know for sure whether, with Luke, I might still be suspect, as I was with other boys, an interloper into those secret intimacies.[27]

Breaching all this is the metamorphosis of an image of desire – ‘his voice, his hand, his bare thighs’ and completing his own subjection to the one conscious of ‘his own power over me’. James sees himself not only subject to that power but also abject before it in return for a mere TOUCH:

… take me, or give me just a touch of you, a hand on my hand, a kiss on the neck, the feel of your breath, the smell of your clothes, that is all I need to be free.[28]

Such freedoms look very unlike freedom and when eventually Luke admits he knows of James’s love for him, he accepts it but only at the denial of any chance of realising together any act of sexual desire. And James must find himself satisfied by this perpetual denial of desire, and even introject it into his take on his future relationships, even with his unnamed husband. Strangely he completes the only love he might expect by virtue of imagined touch again but of the statue of a medieval knight on a tomb, whilst simultaneously thinking of Luke.[29] Whilst knowing the feeling that, unlike Luke, the knight was actually ‘touching him back’ was an illusion, which he explains on the next page as relates to his awareness of the coursing of the blood flow in his own hand, the completion of mutuality stays exactly where it is – encased in the cold stone body of the other partner, and giving away no future hope of continuing desire.

Let’s face it: this novel will yield much more than I can get from it to other readers and this is a sign of its quality. It is also a sign that the queer novel is growing up quickly and understanding its own adolescence as something like that Of James, but also finding in queer love the basis of a philosophy of desire and love in the context of wide spaces of time and place; one that admits it must negotiate somewhere along the line the relationship of chosen to ‘biological and/or otherwise unchosen’ families.

But read this book. Please

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Seán Hewitt (2025:192) Open, Heaven New York, Alfred A. Knopf. Pages references are to the USA first edition. I have just ordered my UK signed edition (to reread it).

[2] Conor Hanratty (2025) RTE [online] ‘Book Of The Week: Open, Heaven by Sean Hewitt’ available at: https://www.rte.ie/culture/2025/0417/1508009-book-of-the-week-open-heaven-by-sean-hewitt/

[3] Sarah Perry (2025) ‘Open, Heaven by Seán Hewitt review – an exquisite tale of first love’ in The Guardian (Thu 24 Apr 2025 07.30 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/apr/24/open-heaven-by-sean-hewitt-review

[4] Seán Hewitt, op.cit: 182 – 184

[5] Sarah Perry op.cit.

[6] Connor Hanratty, op.cit.

[7] Seán Hewitt, op.cit: 5

[8] Ibid: 44

[9] Ibid: 41

[10] Ibid: 49

[11] Ibid: 154

[12] See the double faces, which my be Luke, the latter’s malevolent father-image, or James himself in ibid: 87, 100 – 103.

[13] Ibid: 202

[14] Ibid: 36

[15] Available online from Project Gutenberg as an eBook of Classic Myths, Retold by Mary Catherine Judd https://www.gutenberg.org/files/9855/9855-h/9855-h.htm#xxxviii

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid, 12f. & 191f. respectively

[18] Ibid: 3

[19] Sarah Perry, op[.cit.

[20] Seán Hewitt, op.cit: 201

[21] From: In Memoriam A. H. H. OBIIT MDCCCXXXIII: 121 By Alfred, Lord Tennyson

[22] Seán Hewitt, op.cit: 208

[23] See ibid: 206

[24] Ibid: 61

[25] Ibid: 107

[26] There are more of my thoughts on human, and queer, touch in an earlier blog (see it at this link).

[27] Ibid: 139

[28] Ibid: 141

[29] Ibid: 148