In Heather Christle‘s (2025) In The Rhododendrons many people (with effects of pleasure and pain or hope and despair) continually strike ‘the same pose’ that made images of a possible past recur. Christle tells us that is what family albums do, but that recurrence or repetition within them can, and perhaps should, be perceived ‘differently’. In order to do so, Christle invokes Gertrude Stein’s writing about her ‘group of lively little aunts’. Their speech did have ‘recurrent patterns, but was marked by difference in emphasis, meaning it was not repetition, but insistence’ .[1]

Most people who have been trained in the established academies profess expertise in what it means to read with an eye to finding in a book the ‘figure in the carpet’, the design or pattern that offered a key to the book’s meaning. For these reader’s the task is one that makes claims about their education as readers and their educated readings. But advertising one’s cleverness in spotting hidden patterns in books we read is not what we (by which I mean people who value reading the writing of others or themselves) need from that activity, though at times it may feel that this is the case. This is the inalienable effect of professionalising the role of the reader in types of specialist readers such as the literary professor, reviewer, critic, or other ‘expert’ person of connoiseurial eye. Yet the source of the idiom used here derives ironically from Henry James, whose (in the words of Tamás Ivor Battai cited below) novella of 1896 can be thought to make the nature of reading itself the point of the story.

According to Wolfgang Iser, “The Figure in the Carpet” by Henry James is concerned with questions of the nature of literary meaning. In Iser’s paradigmatic interpretation James’s story juxtaposes two radically different conceptions of meaning: according to one, meaning is something to be found in the text itself and the critic’s job is precisely to “dig up” that meaning. According to the other, meaning is only structured, but not contained, by the text: meaning comes into being in the very process of reading, as reader and text interact with each other. Iser thinks it is this second view of literary meaning James subscribes to. As opposed to Iser, … {in my reading of James}, it is not two different conceptions of meaning that James juxtaposes, but two different modes of reading.[2]

However I intend neither to name nor explicate Battai’s ‘two different modes of reading’ but to use those implied by Christle. In the first we read primarily to pin-down meaning, as a lepidopterist (or lepidopterologist) pins down a moth in their collection, and then to attempt to feel the emotional force of the knowledge this act of interpretation has now put in our possession. Christle in an image I can’t forget, says that some people even read single words as if they needed to be classified under one category:

…, as if the word were a rare specimen displayed in a glass case. It’s pinned down, dead. It cannot hurt me.[3]

The rare specimen dies in order to be preserved just as does the moth in the moment of being pinned-down.

Marek Slusarczyk Museum insect specimen collection drawer with butterflies in Upper Silesian Museum in Bytom (Muzeum Górnośląskie), Bytom, Poland. {Permission details Outside Wikipedia projects you must attribute the work to the author: Marek Ślusarczyk or www.microstock.pl. In case of any doubts feel free to e-mail me: marek (at) microstock pl.}

The second mode of reading is to experience reading as a transit through time and space in which knowledge is emergent from other primary effects which also produce complex and multiply networked meanings: the embodied senses, feelings and interactional meanings produced from the converse between each individual reader and the patterns of words, sounds and rhythms in the text. Both modes of reading are instanced by Christle, and take their binary contexts from the differentiation of life as lived, in which very little is simply binary, notably the ubiquitous child of Heather (Christle) and Chris, Hattie, rarely but at least once ‘she’ but generally using the pronoun ‘they / them’, and the fixed binaries of the once-living but now fully dead. Though this second mode of reading may seem abstruse (at least in my description of it) it is I think more likely to match the mode of reading that occurs most often and amongst most people, who avoid the pedantry of pinned-down words.

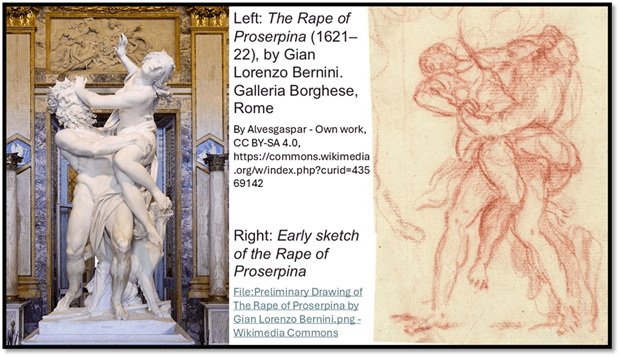

Pinned-down words are of major importance in this artwork mainly because they must be avoided in favour of patterning of a different order, based on repetition and the variants of repetition. Words we will see examined in this book depend on the interaction of at least two, but often more, meanings, such as the name of the town north of Richmond-upon-Thames, Harrow, or even the word or action of deflowering upon which the story of the Rape of Persephone and the consequent rage of her mother Demeter so much depend. For Woolf deflowering is what most people do to books. Christle cites her saying in her essay On Being Ill: ‘We rifle the poets of their flowers’.Flowers are picked throughout the book. All this comes up in the novel in a reference to how Foucault defines a ‘crisis heterotopia’, and Christle wonders if it can be extended to ‘crisis heterochronia’ – spaces and times respectively both outside and yet defined by normative placed space and time (Christle tells us that Foucault examples the word and thing ‘honeymoon’ in relation to the social validation of a deflowering).[4]

And this rejection of the ‘pinned down’ is not unlike the quotation of Virginia Woolf in this book’s Epilogue who would not pin down her trauma to her early rape by her half-brothers, like the experience of Heather’s mother, and like the evasion of a pinned-down narrative of rape to explain Christle’s ‘trauma story’:

Woolf in a letter: “ whether it is right or wrong I don’t know, but directly I’m told what a thing means, it becomes hateful to me’.

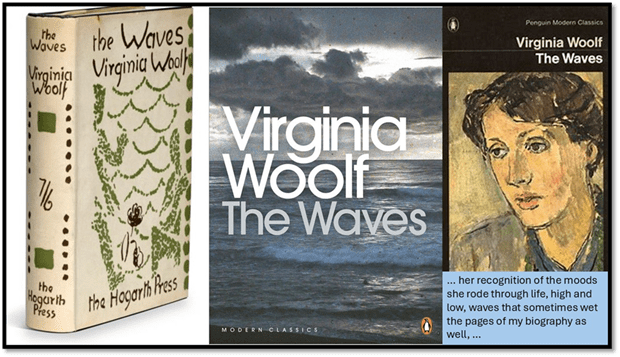

And books are things too. If you pin the down to the meaning found in their pattern or compare that meaning to a legible ‘figure in the carpet’, we pin the carpet (and the book it symbolises, down onto two-dimensional space as certainly as do carpet nails. However, though both Wollf and Christle uses the pattern of repeated waves in their books, neither use them to insist on final meanings, only to insist on their various means of insistence that meaning depends on your mode of reading and not just on the author’s authoritarian control of their material pinning it down to one stable interpretation. Christle says as much – in insisting that though this book is about her rape (that pinned down word of being pinned down by a greater violent force than your own defensive force) it is also not – that it would be merely ‘hateful’ as Woolf says. Speaking of writing the very book any reader at this time can now see they are approaching the end (this is after all the ‘Epilogue’) Christle looks at how she fills in her spare time in when illness delayed her finishing its writing, echoing Virginia Woolf in her illness when speaking of a similar thing, though in a variation of tone:

In the lull I assembled a sentence of words pinned down to their useful meaning, which I hated even as I spoke. I was sexually assaulted when I was fourteen and having my underwear pulled down was very triggering.[5]

The pattern is created by repetition but repetition with all the difference that different reception of the same experience gives. The waves of sound and sense fall repetitively but not exactly in the same formation. They are, as Stein claims of her verbal repetitions, insistent not merely repetitive. They are insistent that pattern and pinned-down meanings are not everything, for if they were the person who is raped would remain a victim and only a victim: not transformed into ‘something, anything else’.[6].

That this is about how people read their own and each other’s lives is an insistent theme of the book. Part of the trauma of the experience of physically violent sexual abuse, especially childhood abuse, is that one gets ‘pinned down’ as pathological – a trauma victim – rather than be supported to transform, though such a desired metamorphosis was wanted by one mother / daughter myth (Demeter and Persephone) and the three life stories which intersect and speak of each other – those of the author, her mother and Viginia Woolf. And potentially this is a pattern that cannot be allowed to pass across time-space, to Hattie, without radical transformation. This is a difficult book to feel comfortable about getting right, and though getting it right may be impossible – for that would be to pin-down its meaning, it can be got wrong. Thus Aaron Woolfson in a sensitive review in the Chicago Review Of Books says:

Can a work of memoir also be a work of poetry? Yes, I’d argue—and not only if it’s written by a poet, as is the case with Heather Christle’s In the Rhododendrons: A Memoir With Appearances by Virginia Woolf. Like a vivid poem, memoir can pursue elusive truths through image and resonance. Often this is the most approachable way into the mystery—or the only way. Some truths cannot be accessed directly. Some questions are hard to ask. Answers hide inside storms of trauma and beneath shrouds of time. You push toward them however you can.[7]

Though Woolfson tells us there is no final truth, only one a trans-genre work ‘pushes towards’, he locks into the descriptions of the book his feeling there may be a final truths (even if ‘elusive’ ones hidden, for instance, ‘inside storms of trauma’ and ‘beneath shrouds of time’). I think myself that Christle not only resists those truths but believes that saying them is forever reductive, unworthy of the work of self and art and intrinsically ‘hateful’, in Virgina Woolf’s term. This does not mean we can either escape or ignore repetitive cycles (waves) in time and space, indeed we both write and read, or both, because this is impossible. However, to want to pin down the truth is a shortening of the meaning of continuing transpersonal life (transpersonal across space and time).

Christle invokes Woolf’s rhythmic variations on repetition (in her writing and, with the difference another life history brings, in the personal reading of it by others ) early in the book, as she senses spatial proximity (even if in a difference of time) in Richmond-upon-Thames, where she might ‘lay the map of my life momentarily over hers’. But we usually think of maps as tracing the pattern of relatively static geographical features, not over the changing surface caused by wind-blown waves in a sea, yet that image of the map immediately turns into a map of the sea’s restless surface or of the surface of internal mood swells that we, and she in resistance, call, using a diagnostic pathology, cyclothymia:

My sense of affinity with Woolf grows not only out of admiration for the words she wrote, her recognition of the moods she rode through life, high and low, waves that sometimes wet the pages of my biography as well, and – I place this at the sentence’s end so it does not crest at pathologizing either one of us – the many ways she approached reading.[8]

Look at that amazing sentence of prose (not poetry as Woolfson tentatively generalises the book) that uses the readers knowledge of syntactic structure to disrupt the rhythm of the whole sentence (verging on iambic metre) and resist the fact that we see emotive metaphor and rhythm as sometimes the stuff of pinned-down lives – lives turned into pathological symptoms by useful pinned-down words for this diagnosis. And note that as well as disrupted rhythms, this process works by mixing up the contexts from which metaphor derives – like the two-dimensional map above, turning into a restless surface. And what of internal rhyme, and other patterns in the writers quiver of arrows of desire. At one point Christle speaks of her mother’s obsessive-compulsive (if we must have a labelling adjective to pin down what occurs here) care for some expensive blue wineglasses given to her by a rich friend which were saved from use by drinking being prohibited from them. Shouldn’t her mother let go of this obsessive compulsion Christle wonders:

But that’s easy, it’s so easy to ask someone else to let go. How much harder to watch your own precious things break. And I know that I must. I can’t ask of my mother what I refuse to ask of myself. So:

I never saw any yarrow at Kew, nor on the Downs.

The pub menu I ordered from at the Sunday family lunch called the zucchini courgettes, not vegetable marrow.

Until I began writing this book I had never heard the word scarrow and am not at all sure that I’ve used it correctly.

I have no idea whether the cows in the fields near Charleston were pregnant or farrow.

Eary on, I decided this book must contain precisely two occurrences of every two-syllable word ending in -arrow (barrow, harrow, narrow, sparrow…) making each one of a pair.

I realize this is unlikely to matter much to anyone beyond myself. I imagine my pairs could seem insignificant next to my mother’s blue heirlooms, but I still hope you-and she-might understand what it takes for me to relinquish them now. Through years of composition, across a treacherous sequence of increasingly personal drafts, I maintained my meticulous pattern. It felt like a life vest I could put on when I was afraid that writing the book would kill me.

Now I have broken it.[9]

I find that passage of writing simply amazing. If the words mentioned here are chosen for their rhymes it does not rule out their possible associative semantics with symbol and myth (yarrow in particular). But what I noted as I read is that there is a compulsive side of me that wants to check out the facts and find the reference to these words in the past text I read. That compulsion is heightened by my obsession about having failed to have noticed the requisite detail of lexical choices as I read. Did my mood on reading notice the references to yarrow in Kew Gardens, vegetable marrow (with its visceral connotation (being absent in the term courgette) in a pub restaurant menu and a possible ‘incorrect’ (or not) use of the word ‘scarrow’ (a word anyway that is highly contended between cultures and etymological sources and hence the decision about correct use or not is not really solvable).[10]

Did I not notice either the private pattern of internal rhymes with the two syllables in the word ending ‘arrow’ (itself a pointed wounding word used in love – Cupid – and death – with his dart – references)? Does this mean (I pity myself again!) that I could not feel the loss of this arrow pattern’s point as a repeated sound-effect widely associated with fluid and unpinned-down associations? Does this mean I became dependent on the author and her pattern-making because I did not see them until Christle as author told me about them. As I rescan this book – felt it demanded of me – I felt I might weep now as I saw Christle’s adventures in writing visited those tragic ones in Virginia Woolf’s last rendezvous with swimming and drowning in the ‘small waves of the high tide’ (swimming, drowning, waves and tides being essential repeated motifs in both writers) for so much in the chance of a life continuing hangs on it:

I feel an urge, large now, to climb down the steps and into the river. It is not that I want to drown. I want to transform. I want to be something, anything else.[11]

I cited those sentences earlier but thy are magnificent when seen in full and reading Virginia Woolf’s The Waves fuses with her death in the River Ouse, and the way comprehension sometimes drowns too in complexly patterned prose or poetry or both, as in The Waves for instance, of which one character in Christle’s book admits he has only ‘read’ half – but what, we ask ourselves does this lovely man afeared of rutting deer. Once we read associatively, we see association everywhere crocheting its pattern through the book. Take that reference to why Christle maintained ‘my meticulous pattern’ of arrow rhymes in her book. She says:

It felt like a life vest I could put on when I was afraid that writing the book would kill me.

That books which define the patterns that explicate an author locking herself into ‘a closet’ (she even jokes with this as any queer reader will notice when she says she omitted from her memory-list of the men ment she slept with, the one woman also potential to the list) and her suicide attempts do in a sense kill their author if the pattern is completed and tie them down. No book has so clearly, though it is implied by autofictions by Voltaire and De Quincey, illustrate that the problem of writing memoir is also its redemption: ‘The problem of writing life is that it continues’.[12] And it continues even when life-vests are seen as inadequate. As I write this I turn to this comparison of a photograph of both Woolf and Christle with their respective mothers. Christle is scrolling through images of Virginia Woolf’s life, finding one with her mother Julia. She tells us:

I knew, I thought, that shape. From where? I watched the matching image float up from the depth of memory until it fully surfaced: a photograph from one of my own family albums.

Still thinking that she would in reality ‘find the pair ….’ (but read the continuation and the self-conscious joke about the life-vest below in the image from page 71 of the book):

This is both playful and controlled. This writer sends a ‘wave’ to the gods whilst floating on a metaphoric body of water that might or might not be the ‘sea of life’. But the point is that she is aware that life-vests in a way pin you down, unlike the decision to swim that is made by Christle and urged upon her by Hattie. When you swim, you can swim even against the current of a river or the ides of the sea – even in that ‘river of ink’ (another thing to float upon) or swim with or against), the Fleet, where on a street crossing and named after it, ’Wynkyn de Worde set up his printing press in 1500’ or the time of onward flowing history.[13] As she does this swimming, I couldn’t help noticing she was fading out of a conversation with her fiend, and wonderful artist, Kavek Akbar, whose notice of this book on its covers first drew me to it (for the blog on Akbar’s Martyr see this link).

I made many notes on this book as I read and then re-read it and thought I would be interested mainly in its handling of time as cyclical or sequential or both and the role of both writing and reading in this process. But leave that to the academics. Instead let’s just notice that time ‘collapsed’ for Christle really only when her book celebrates continuing life beyond suicidal ideation, plans or actions: it is the insistence that replaces repetition (the latter is the source of melancholia in Freud’s thinking): ‘the insistence on that one moment, that snow, that “I am still alive”’.[14] It is an insistence she finds on the same page in other artists – best perhaps in Wallace Stevens, where what is going to happen, though it is already happening is the promise of continuation of living:

It was evening all afternoon. It was snowing And it was going to snow.

Great artists, in my mind, still tell us about the sins of the political world with which we choose to collude. Historians need facts to be pinned down by evidence (usually in paper documents), but that need is only the other half of the recognition that anything pinned down is easier to cancel or erase from history. Revising ‘cultural priorities’ matters as much as patterning history by virtue of statues we protect by law. Thus the very same colonial attitudes that burned the records of the evils of British imperialism, now defend the statues of acknowledged violent colonialists (Cecil Rhodes) and slavers (Bristol’s Coulson) as if they were pinning down history in the interests of the entitled of the statis quo.[15] Patterns that are fixed pin down for ever – patterns that acknowledge they had a use in a past life can also evaluate that use and revise cultural priorities and thus we are with life. I sense that the new revised priorities in this book are to fill out with action the life of non-binary Hattie.

In summary then, I think this book recognises that the future is one not of the biological contingency that back up, often by fallacious biological assumptions, notions of bloodline in family and nation, but of the admixture with biological contingencies seen as they are (without ideology) of images of chosen (family) others, living and dead, whose relationship is more than an echo or an ‘appearance’ (like that of a recurrent ghost). In being more than echoes or appearances, these images borrows flesh and blood where they can – usually from the still living – to reanimate their lives and/or words. Woolf does this for Christle’s mother in order to allow Heather to re-evaluate her mother’s life – in continuation but also, against, the current, in a past that was suppressed. It will do so not by the use of pathological categories by a true understanding that repetition is insistent – insistent upon continuation that is as transpersonal rather than personal, the view of that neglected British philosopher Derek Parfitt.

That’s all. Now for a rest!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Heather Christle (2025: 103) In The Rhododendrons: A Memoir with Appearances by Virginia Woolf –

[2] Tamás Ivor Battai ‘Getting at The Figure in the Carpet’ available at: https://ojs.elte.hu › theanachronist › article › download · PDF file

[3] Heather Christle op.cit.: 49

[4] Ibid: 47f.

[5] Ibid: 247. Italics in original text.

[6] ibid: 203 Quoted more fully below.

[7] Available at: https://chireviewofbooks.com/2025/04/28/unaskable-questions-in-heather-christles-in-the-rhododendrons/

[8] Heather Cristle op.cit: 27f.

[9] Ibid: 227f.

[10] For its etymological origins as a name from the Old Norse for seagull or cormorant see Scarrow – Name Meaning and Origin. For the meaning related to half-light (also claiming Old Norse and Greek etymology) see SCARROW Definition & Meaning – Merriam-Webster.

[11] Heather Christle, op.cit: 203

[12] Ibid: 245

[13] Ibid: 48

[14] Ibid: 66

[15] Read ibid: 105