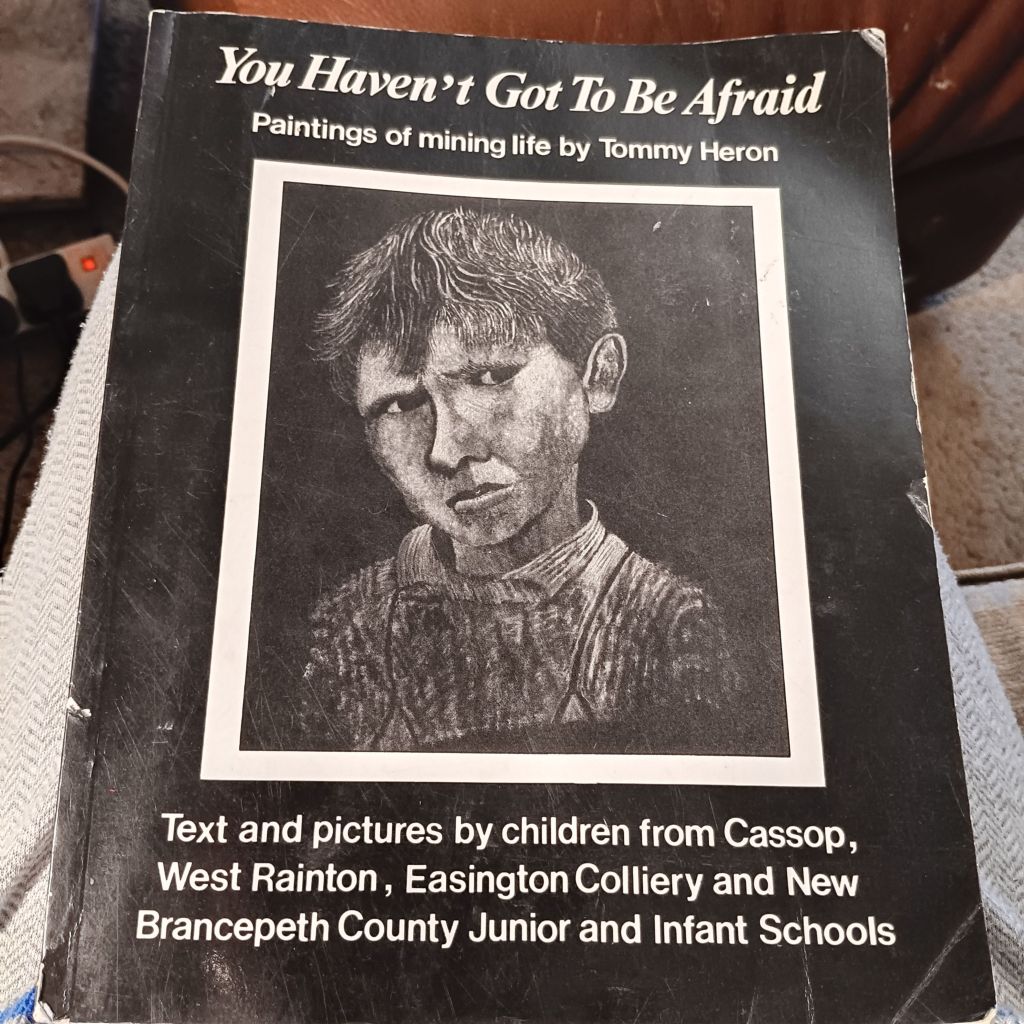

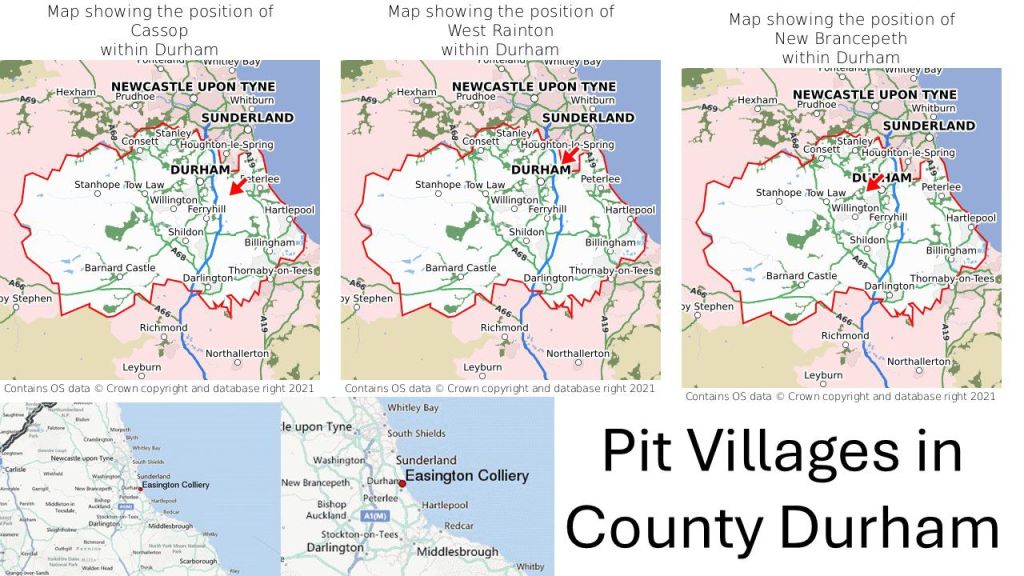

Geoff brought me a gift from his day volunteering at Oxfam to include in my mining books. It is a pamphlet published in 1990 by Durham Arts Association. It charts encounters by a retired miner, of 40 years work down pits, who was dedicating the time released to his lifelong wanting to produce art with several junior and infant schools across County Durham. Lotte Shankland, who writes tbe pamphlet’s introduction, first met Tommy in 1986, and she began a project working with the children, for all of whom the pits were then a fact of their older families’ lives but to them, as one boy said about the stories concerning those lives they were “just like a fairy-tale”. All of these children came from communities in which all the pits were closed; the last to close [in 1983], but for Easington which limped on, being near Cassop after the Miners’ Strike.

Lotte persuaded Tommy to visit the chosen schools and talk to the children about his art.

The children, on their part, seemed fascinated by the fact that he chose to work only in black and white, not many colours. He told them:

There’s no colour in the pit – just the light from your lamp and what the light falls on. That’s all you’ve got to go on when you paint. You haven’t got to be afraid’.

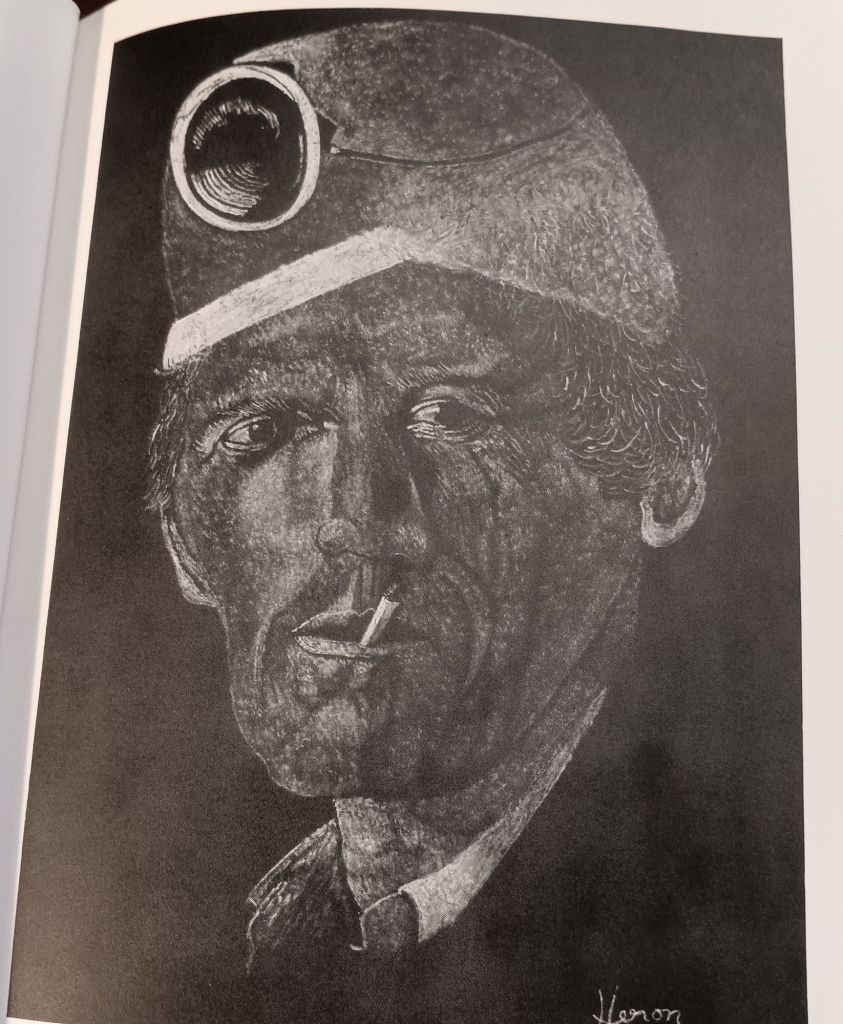

That last sentence was chosen to represent the collection of reproduced paintings and the children’s contributions in prose or verse in response to their own understanding of the paintings. There is always an issue to think about when we think about how children process adult anxiety and attempts to be resilient in the face of that anxiety. To the self-portrait above, I find no responses, so here is my own. What I see is a man who lives in shadows, and hence, his look is hard to read because of these shadows that seem to proceed from his eyes to darken his own forehead. Even his smile seems ambiguous. But look at his clothes, this man is no longer a pit man but a man who has either given up the pit (or the pit has given him up by closing prematurely). The beliefs that sustained him – community, fellowship, and the love of God – seem distant now, and these beliefs seem threatened in his dark visions of his community as it seems to him now.

These paintings do not glorify the days of the pit village as it was in Tommy’s youth or kind of childhood experienced in that past, as in the picture of a child outside a closed door shoeless above, pensive as the evening comes on. How does these children of 1990 process this? Take young Daniel Thompson writing about the shoeless boy. He notices that the boy has no shoes and that this defined his sadness, although his explanation of it seems to miss the darker elements of the picture, perhaps because that might be too difficult or painful to imagine. Daniel finds the boy’s sadness to relate to being grounded by his mother because it is dark or because he has no shoes or for some other reason.

What Daniel cannot see, it seems, is that boy, far from being shut inside his home, is shut outside it, standing against a door that is barring his entry. The hardness of such a punishment is barely to be countenanced by Daniel, whose sadness still relates to the denial of the opportunity of outside adventure rather than of the relatively warmer space of a home – only relatively because no warm home excludes its sons, whatever their faults.

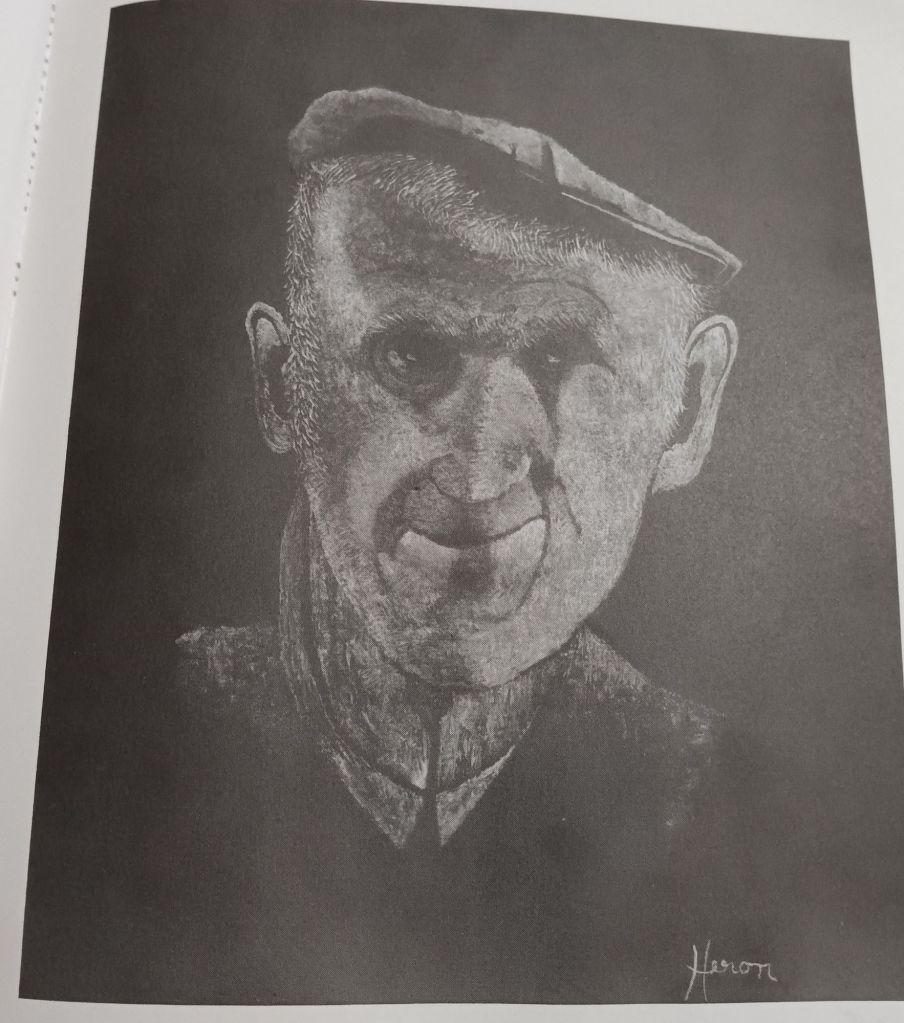

When children think of ageing in this book, they see it as unrelated to themselves. They look, for instance, at this picture of an older man, whose eyes scrutinise their viewer.

Gavin Luke thinks that the ‘wrinkles’ of the old miner are ‘accurate’ (a hard word for a junior school child) because they reflect the man ‘thinking hard about his life’, in what Gavin thinks were ‘dull days’. The walking stick reflects not the wear and year of age but is there ‘because ‘there was a fall on his leg’, a fall presumably of badly shored coal. Dale Scott says the events of this man’s life were 200 years ago. William Dunstone sees him not as an old man but a ‘poor man’. Interestingly enough, adult darkness is an effect of events not of something more internal to the person.

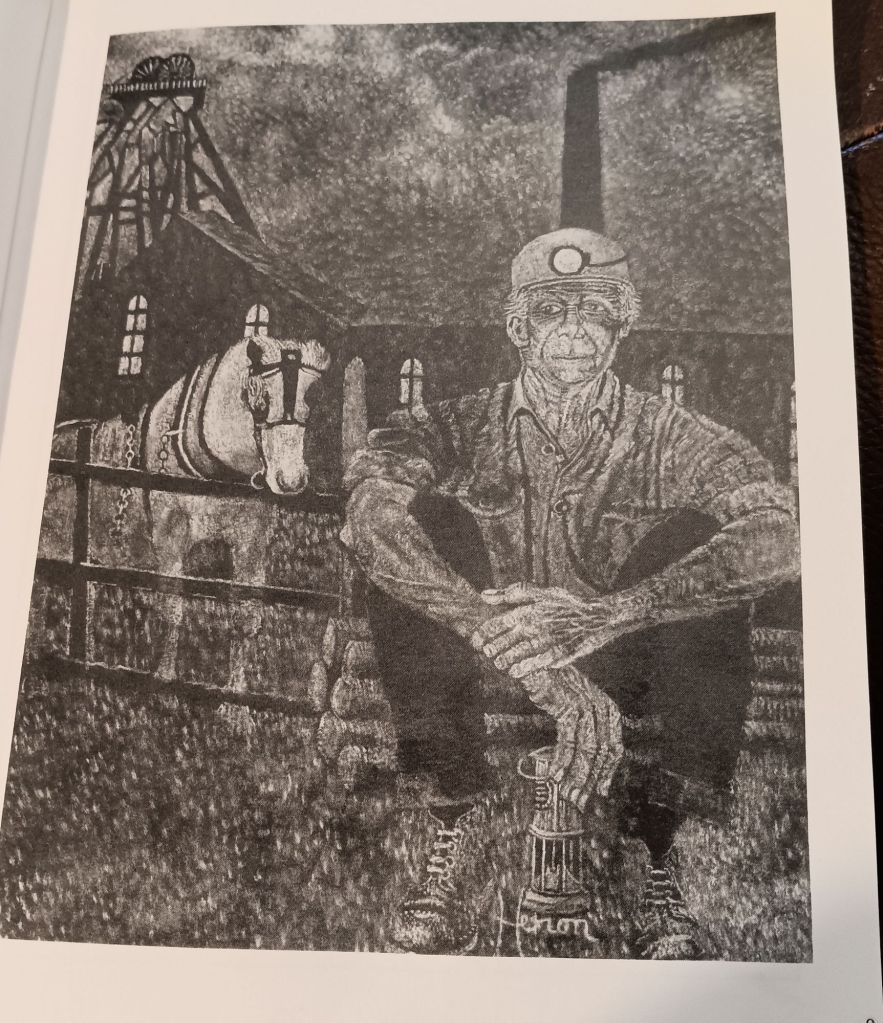

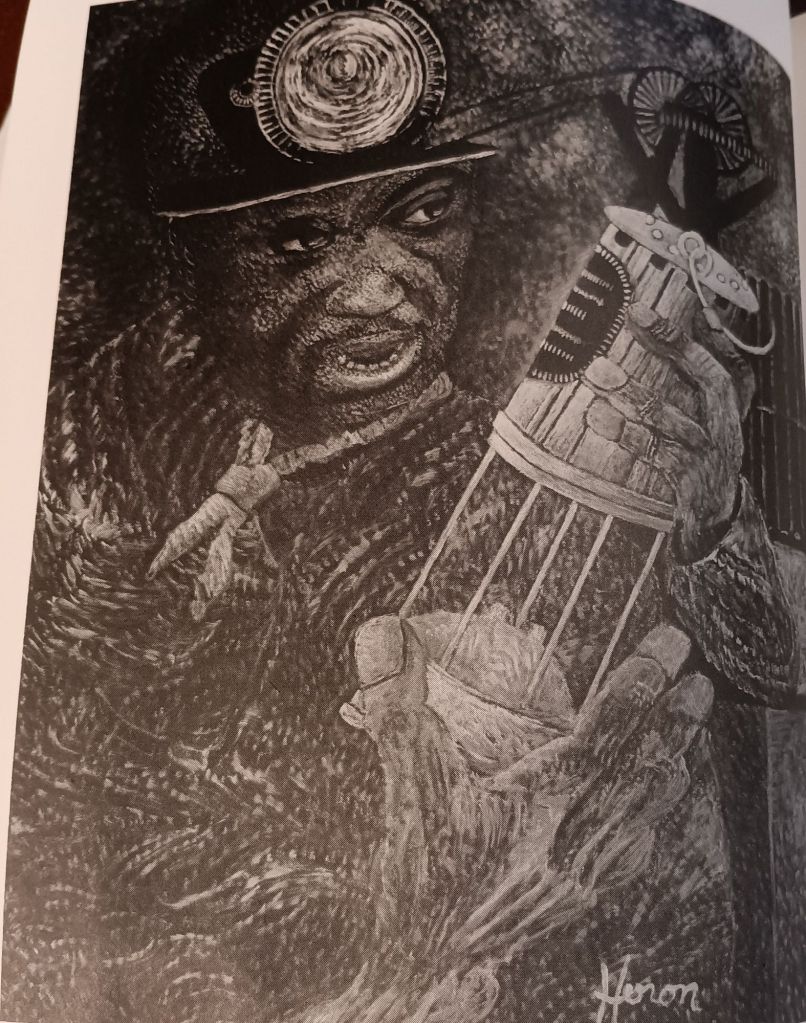

Given more contextual information, the children still tend to find remote possibilities to explain adult emotion or to deflect it onto animals, particularly the pit pony who becomes the emotional centre of this dark painting in which nothing speaks of hope, either environmentally or otherwise. The miner’s electric battery-powered headlamp still shines, though he is outside the pit, but not in mood, it seems.

The children accept that these days are the past, ‘dull days’ as Gavin says, but have no way of seeing that the paintings themselves are deliberately anachronistic. Davy lamps were never a good source of lighting, whether hooked to a belt or held, and their replacement by electic-batyery powered helmet lamps was an important step forward. Strangely, Tommy usually has his men with both lighting sources, even where one is redundant or would hinder the work, as below.

These lights serve to unite across time the fact that mining is a dark as well as a hard life.Gary Burns gets that in a poem he calls The Miner’s Poem:

The Miner's light

is burning for the miners

Of long ago.

A mining life is precarious because it is dark. The miners above mend one pit prop whilst not noticing another nearby is splintering below their gaze and seen perhaps only by us. The young children see it simply as if the dark where the sum of the negative, everthing light is not, according to Marie Hales:

The pit is black

There are railway tracks

The pit is made of wood and coal

The pit is black

The miners' faces are black.

The pit pony theme returns in the underground painting where four men and one boy confront the viewer as if they were an obstacle in the pit tunnel. It is an anachronistic painting. David Schofield mentions the three men and one boy have funny hats, and certainly these are not the compulsory pit helmets of the 1990s. These men are out of place. They are not dressed as if in the pit, though they have rather redundant iconic Davy lamps. Where we sit and gaze is further on in the tunnel looking back on them as images from the past. The symbolicDavy lights they hold up are because we are their dark future – but dark not jute because of black that is shed from cut coal but because we are the unknown to them. Much of what we see are anachronisms – miners dressed for the outside but inside carrying symbols of past labour, even of the aids to that labour from the past – the pit ponies.

It is the pit ponies to which the children let their pity turn perhaps: ‘Pit pony plodding down the rail’ dats Nicola Chambers. But nothing is solid in this mine. David Schofield mentions that he has noticed a broken pit prop – indeed at the point of crashing in – but decides:

it was still safe to work there. It could not fall at all, one man checked it every day. just in case it did fall.

Hah! What a witness to the insistent optimism of infancy, but what, too, a sign of its contradictory precarity. Maybe adults still are not to be trusted at that age. Note below what Michael Carl Kirk says of a hyper-realistic painting of the modern miner with electric helmet-light:

Has Michael used ‘devious’ as he intended it. Whether or not, ol;der men doubt the young and must be themselves doubted and probed in return. Adults are strange creatures – men like the one Tommy paints below seems not too concerned about pit life.

It is a ‘dreaded pit’ but is forgotten in the ‘normality’ of football matches and friends who feel the same about work: each ‘Working impatiently for his pay’. Though of the same man Rachel Purvis tries to see what Tommy is about by painting him – and by the detail in the painting, but nevertheless the figure created is a kind of threat to her:

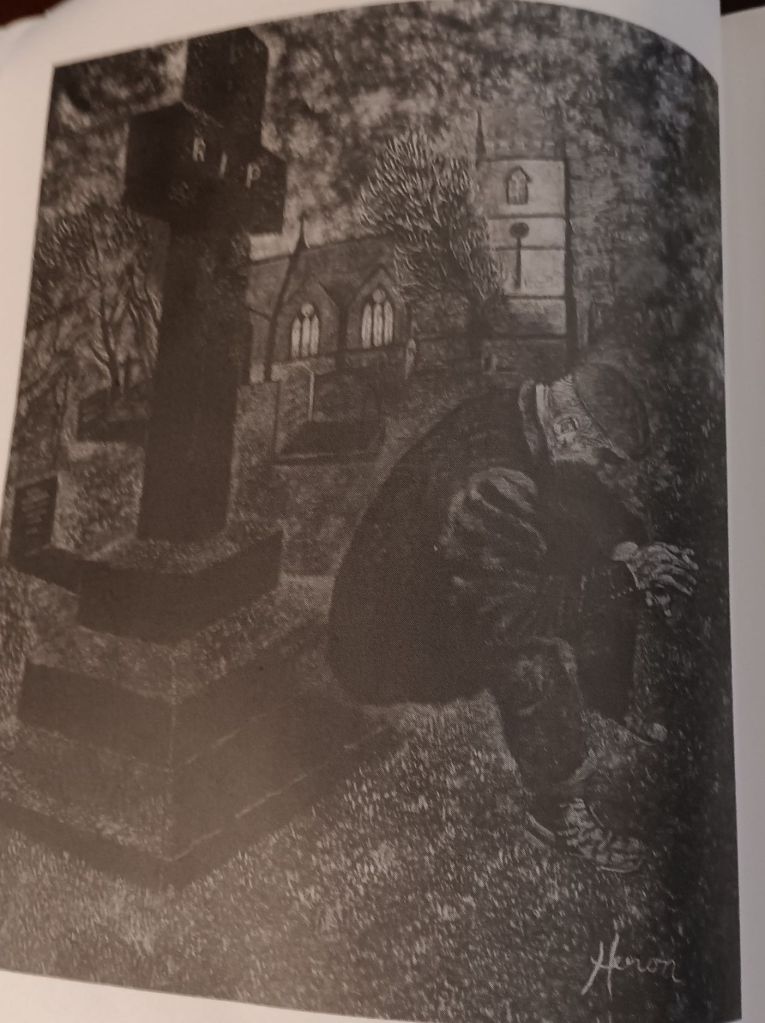

When it comes to adult sorrow, how might they deal with this, a miner sitting in the dark (it must be evening for the church windows glow) at a headstone marked RIP on which his back is turned. Steven Firby decides the miner mourns ‘his old friend, Tom’ and ‘the good times they had down the mine’: the mood about mining seems an elegy for a life already past.

Other children imagine another mourned person or even community – it is an icon not of one person for Louise Dunn but for:

Eighty-three men who died.

Oh, how women and children cried.

It took months for our community to settle.

Clare Lawson imagines who is mourned is this miner’s son: ‘he was only two, my only son’. Lindsey Peters thinks it was the miner’s cousin who died long ago but for Howard Blindt, who knows some coal-face dialect it was the miner’s ‘marrer, his mate’, Eddie.

Here lies Eddie,

A real mate.

But seeing a picture of miners returning home, it the dull future the children imagone for these isolsted men looking forward with glazed tired eyes:

PHOTO

He goes home to see his wife,

He'll probably work in the mine

All his life.

Does Ben Walsh in the poem above rhyme ‘wife’ with ‘life’ for a reason. Tommy’d pictures of a miner’s home life present it as a kind of place a miner isn’t necessarily any more happy. Take the picture below, where images of established religion and the frosty stare of his wife offer little of love despite the legend over the hearth ‘God Is Love’. Locked into her religious tract the wife here has no empathy for her husband and even his dog is puzzled.

This is a very dark picture indeed. Donna Parkin had a go at writing about it, picturing the man as Jack – happier out at the club, aware that only money holds back Edie, his wife from shouting. Home from the club: ‘When Edie calls “Jack” I cover my head’. This is a very funny take on domestic tragedy. Is this how Donna sees it?

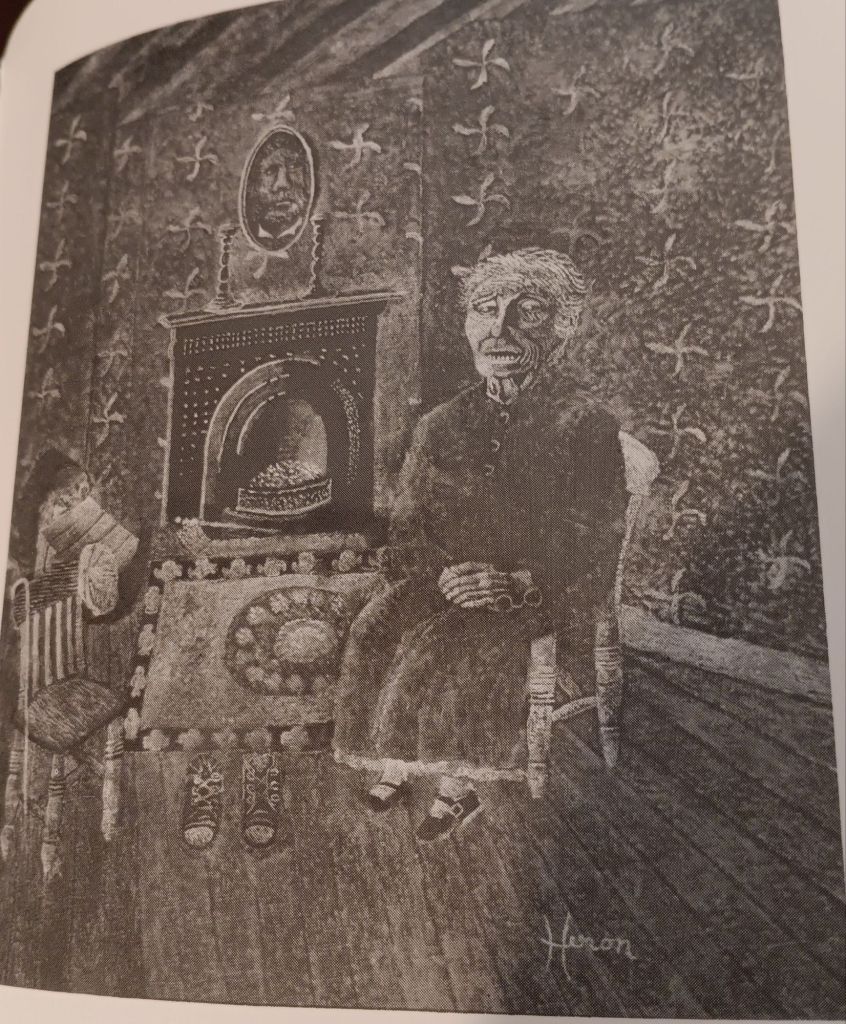

Yet Tommy Heron supplies a picture too of the tragedy of bereavement and widowhood: a woman with panic in her eyes sits stock still, afraid of both motion and emotion: her husband’s chair empty, his boots just stood before the table and his picture over the hearth.

Lisa Sweeney sweeps all the detail away and harmonises the lady with her lot. Do children need to do that? The fire, by the way, seems not yet lit to me.

A lady is sitting on a chair,

The fire's on, nice and warm.

A picture is on the wall.

She has little shoes on.

the wall is covered in patterns.

The little lady's looking smart and thoughtful.

Perhaps the most interesting piece however returns us some features of mining communities that feel anachronistic. In the picture beow, a miner with a modern helmet lamp investigates a Davy Lamp., which unlike the helmet lamp does not appear to be lit. Gayle Lisgo gives a great description of the picture, ending it with: ‘He is a black miner’.

Racism was, and still is, an issue in the Durham coalfields (Durham is one of the few County Councils run by Reform) – Tommy Heron silently addresses the racism of its past by the usual ‘light’ imagery and this must throw some of the imagery of the black and the dark that that the children pick up in other poems of thirs on reflecting on Tommy Heron’. Stuart Lund appears colour-blind to the fact of the man’s skin-colour which makes the last line of his poem the more pregnant:

He comes home tired

Covered with pitch black coal

In other poems, the children relish the association of black with negation – here perhaps – perhaps! – they begin to see that word associations are problematic. Thank goodness I am not a teacher!

I can’t ask you to read this book. It is too rare. But oh to see some of the man’s work properly.

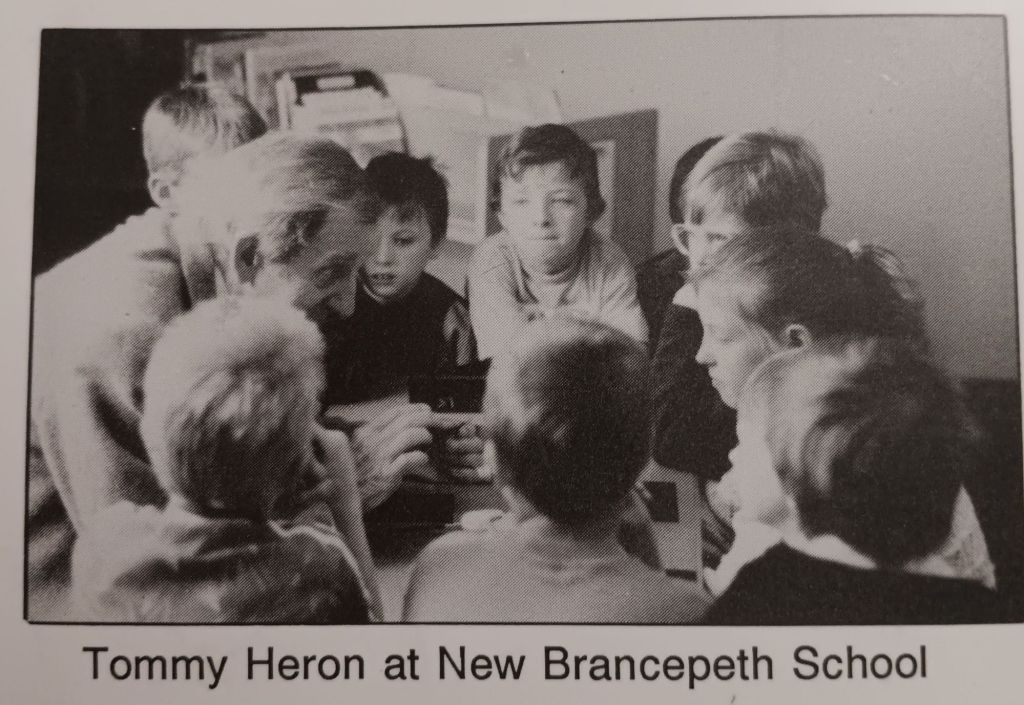

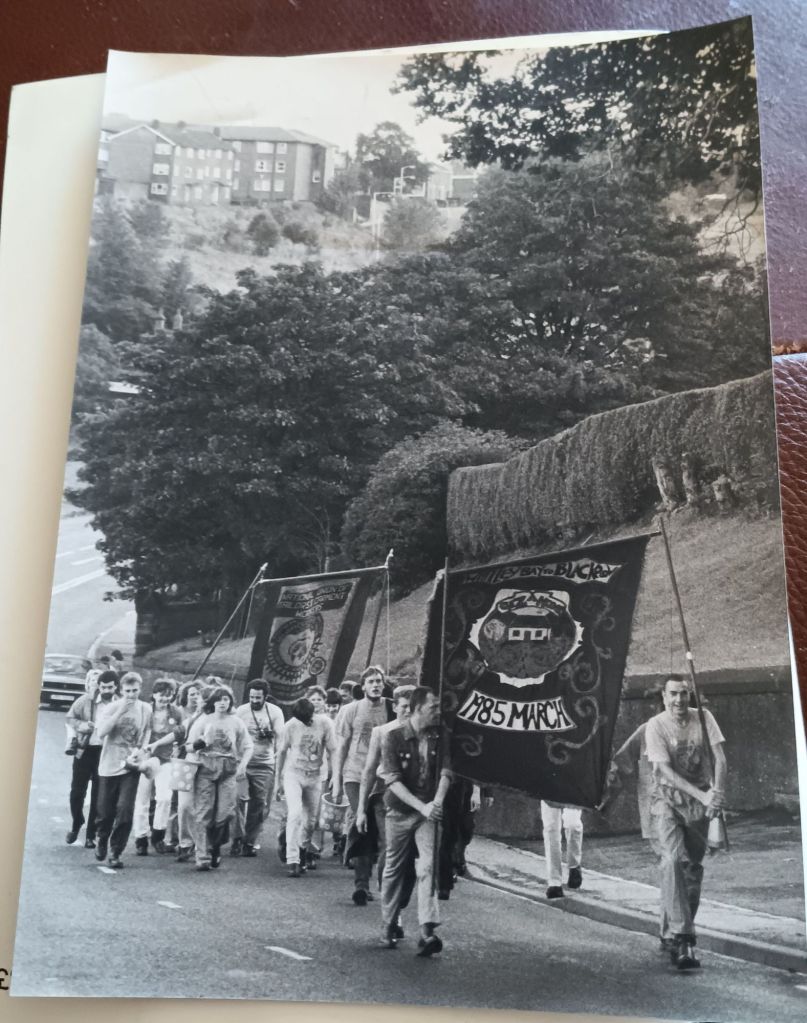

Oh! By the way, PS: the book had in it the fine photograph below. To be framed!

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx