‘Only connect’ said E.M. Forster but what madness results. Begin by making connections between these two photographs and then with them. Roland Barthes [trans. This blog reflects on Roland Barthes [trans. Richard Howard] (2000:3) Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, Vintage Press Edition.

Connectivity was always a thing I valued – in the connection for instance of different modes of sensation into some synaesthetic whole, but then again at another level of understanding I wanted (I desired indeed) those connected sensations to connect again with other modes of knowing things – through thought, feeling and interaction. But surely there have to be limits? For the first time ever I have read Roland Barthes late treatise on photography, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (La Chambre Claire in French) in which many photographs appear through contemplation of all of which and their connections, but most through th3 connections the images make to him – how they ‘prick’, leaving a small remnat of their contact, a hole or space – Barthes attempts to solve the fact that, in looking at photographs, he had become:

overcome by an “ontological” desire: I wanted to learn at all costs what photography was “in itself”, by what essential feature it was to be distinguished from the community of images. [1]

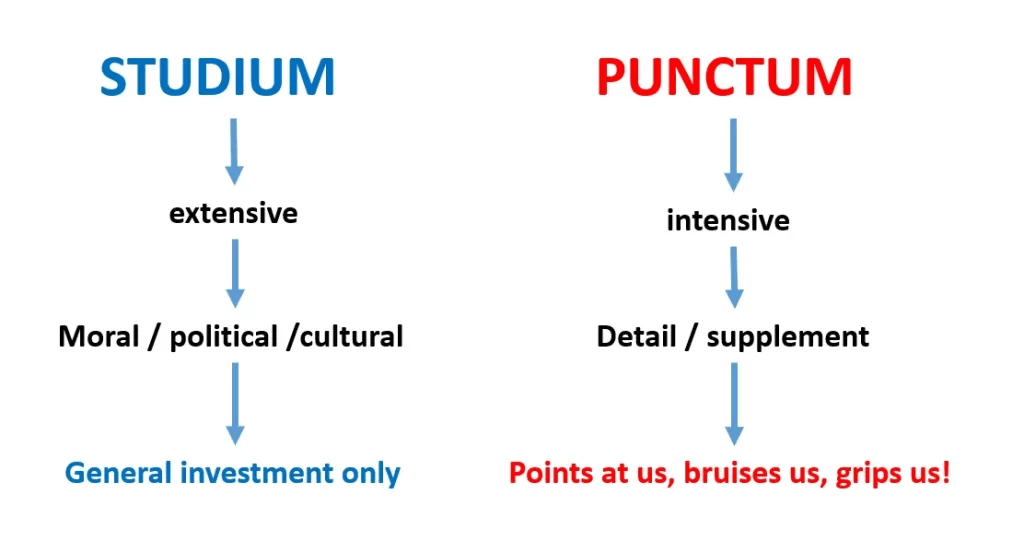

Ontology is the branch of metaphysics that is the study of the nature of the essential being of something, rather than the study of how you can know that being, called epistemology. This idea excites. Hence, as I read on, my synapses crackled in an attempt to make connections between the things in the book, their prose descriptions, the photographs, and Barthes’ direct and indirect reflection on himself. I thought I might blog on these connections in the definition of the essence of photography, but it seemed too large an enterprise – besides I think so much of the effect of Barthes prose demands awareness of the multiple connections between domains of human being that the subtle usage of of his own French language can make. Take his main distinction in Part 1 of the book between two contrasting effects in a photograph – one of which he names, utilizing Latin as he often does, its ‘studium‘, which comprises all the ways in which one might like a photograph (without implying ‘study’ of it) and comprising all the aspects of a photograph which help an observer to ‘participate in the figures, the faces, the gestures, the settings, the actions‘ of the photograph.

But the other effect allows us to love rather than like a photograph – it is this he names (again evoking Latin) its ‘punctum’. It is in these descriptions that Barthes’ linguistic play is at its potentially greatest in the original French I suspect, though the play remains in the English version where punctum is described as ‘this wound, this prick, this mark made by a pointed instrument‘, creating ‘sensitive points‘ in the personal effects of meanings of the photograph for a specific viewer, that are defined by contingencies (or accidents) in the meeting point of image and a specific viewer and their history: ‘that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me)’. [2]

I cannot find a French text and so cannot look for the play that occurs linguistically around the definition of ‘punctum’, and the frequency of pricks in its vicinity, but the lingering air of violently inflicted desire hangs over it – just as orgasm does over the use of the word ‘jouissance’ to name the extreme degree of semiotic pleasure of reading complex texts in his more famous texts The Pleasure of the Text and S/Z. But you feel you need to play with Barthes’ text in Camera Lucida even more than in The Pleasure of the Text, so I set myself a task.

Some commentators argue that Part Two of Camera Lucida is another entirely unconnected text, merely dangling from the greater rigour of semiotic science in Part One, but that is to simplify both parts. Part Two is different since it concerns mainly his response to finding a childhood photograph of his mother soon after her death and his abandonment, as he felt it. But the connection is there – it is just held in reserve for the reader willing to give of themselves to this text, just as, he shows us, he has given himself to Proust’s descriptions of the death of his grandmother. In my view too this somewhere connects us to the two writers differences and commonalities as queer men.

Towards the end of Part Two Barthes returns to find the deepest level he can think of in which images ‘had “pricked”‘ him (‘since this is the action of the punctum‘ he adds in case you miss the point of the violent take -over of one’s defences that is involved). [3] At this point he is connecting in the text a whole load of experiences and photographs – from ‘a young boy’ who looks at him in a cafe without ‘seeing‘ him to a photograph by Kertész, called The Puppy, which he shares with us. From there he look at at how Proust evokes feeling for persons based on real people for whom photographs exist. Is, he wonders, the connection between them the ‘air’ of attitude of each example, an air he calls ‘The Look’, and which seems to connect them to the studium qualities of photography, or is it something deeper – an emotional connection akin to pity – something that might wound where we to catch its point of pricking connection to ourselves.

As I have already implied, if Forster’s advice to ‘Only connect’ means anything, we might make connections between any number of things, including ourselves to each of the images we collect together through our lives. But it means more too. Personally, as I hinted, I like to connect the data of different means of sensation – a synaesthetic whole where the eyes, olfactory organs and ears perceive connectedly. It should not stop there. At another level of attempting to know ourselves and the world, we invoke a connective pattern of thought, feeling, (or affect and cognition if you prefer),action and sensation so that we might attempt to link it all together into some network that is, in the end, the definition (vague and inchoate though such a definition might be) of our human essence.

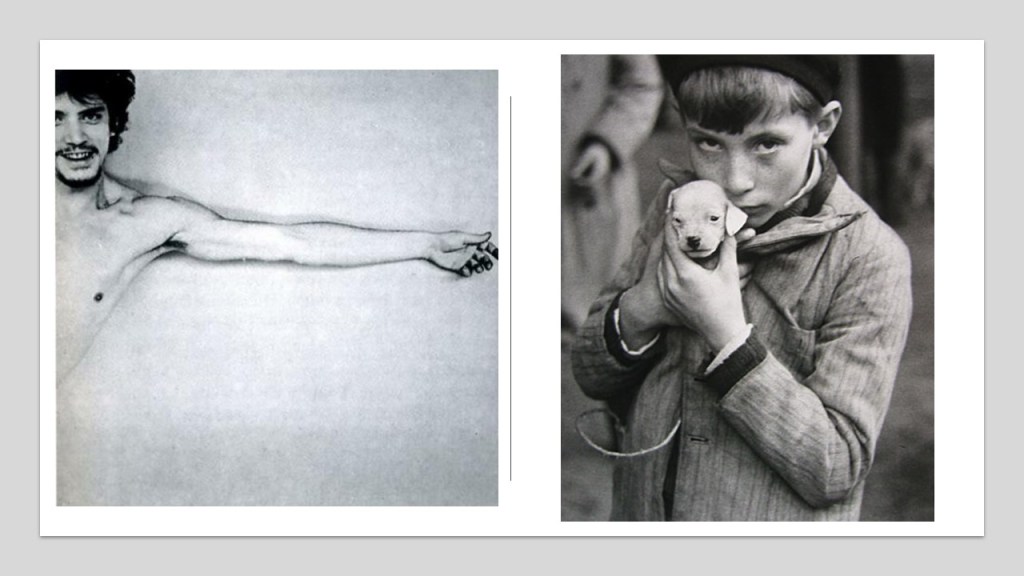

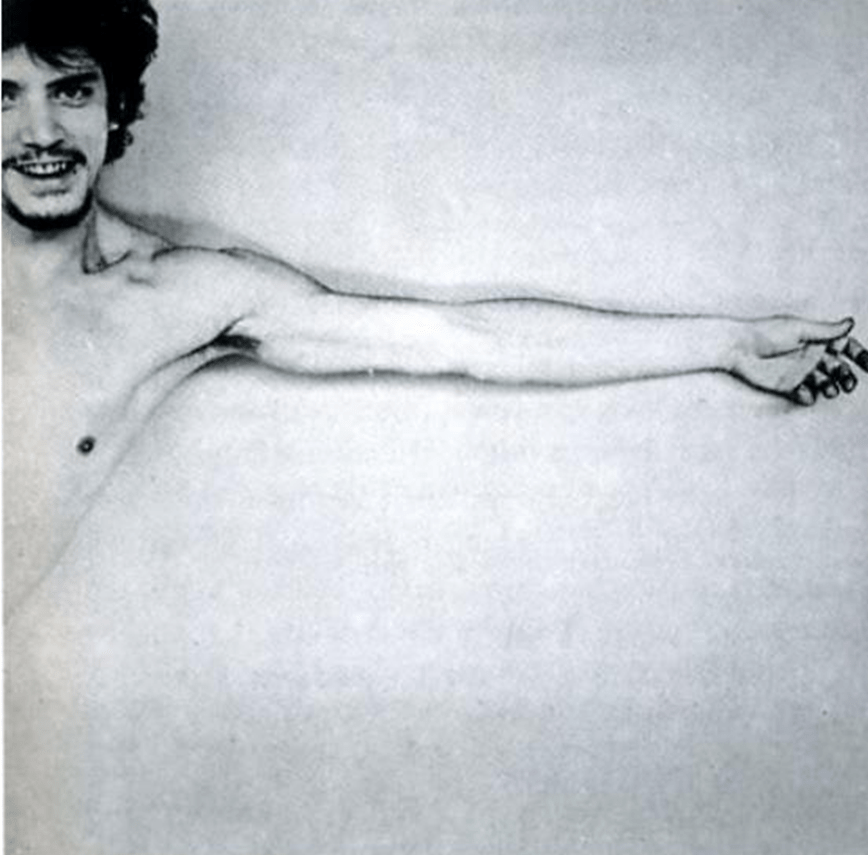

At that point I thought I would try an experiment and take two photographs offered by Barthes to illustrate different levels of the agency of the punctum in the photograph, though he does not look at both at the same time, as I try to do. The second I have already mentioned. It is that one by A. Kertész, called The Puppy (Paris 1928), as he labels its reproduction. The first is, in his label, ‘R. Mapplethorpe, Young Man with Arm Extending‘. See them below. Maybe try to connect them!

Barthes describes The Puppy as of a ‘lower-class boy who holds a newborn puppy against his cheek, … looks into the lens with his sad, jealous, fearful eyes: what pitiable lacerating pensiveness! In fact, he is looking at nothing; he retains within himself his love and his fear’. Going on to link the punctum here with the quality of the punctum intrinsic to Photography, he finds beyond the studium or look that which he uses Nietzsche to illustrate. That is its appeal to our own inner crazy Pity for the other, illustrating it by Nietzsche throwing himself on the neck of a horse that was being beaten: ‘gone mad for Pity’s sake’.

We will never know how Barthes got to see the reserve of vulnerability, jealousy, and fear hidden behind the eyes of the boy with a puppy. Is it that that he holds the puppy in a way that might be care but might also yet be the threat of violence by strangulation of a thing more vulnerable and lost than he, at the point of its birth it can be cut off from life. For me, the punctum – which in other photographs Barthes finds in the presence of an inexplicable bandage on a photograph of learning disabled children, is the rope peeping from the boy’s jacket – perhaps a makeshift dog-lead to posses the young life as his own, or perhaps a rope to strangle the unwanted runt of an over-large litter of puppies that cannot all be fed.

But then the boy too may well be dead now as Barthes goes on to point out with other examples. How can we connect this kind of associative complex humanity with the Mapplethorpe picture from Part One.

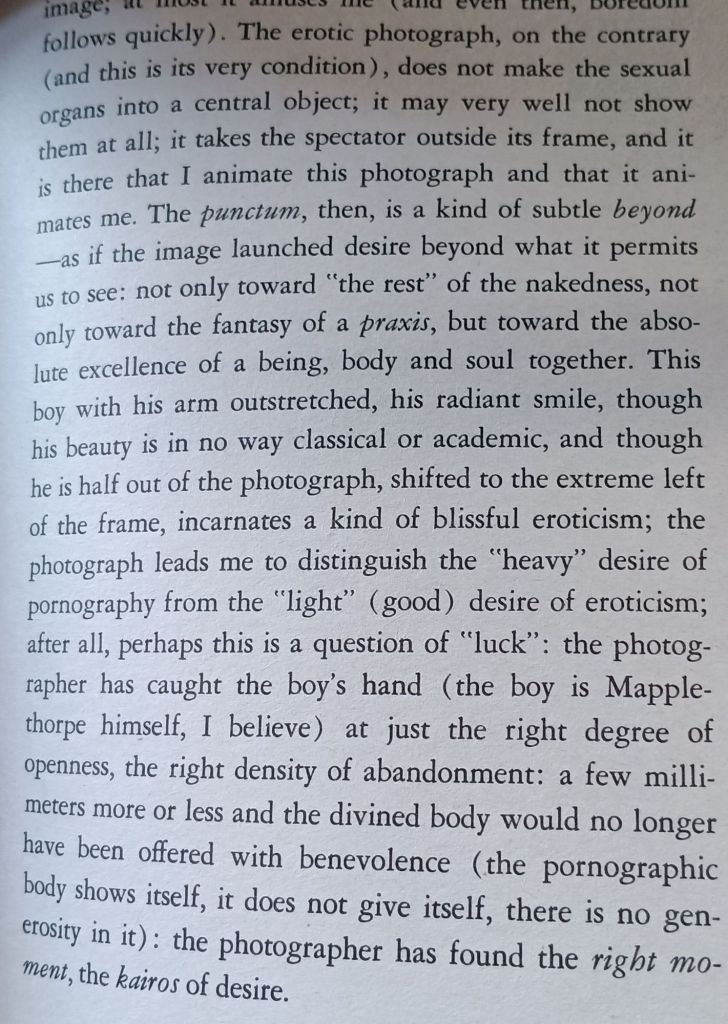

Barthes uses the Mapplethorpe photograph (he slides into his description the fact of his own awareness that this photograph is Mapplethorpe’s self-portrait) to show that another function of the punctum of a picture is to distinguish pornography from eroticism. Read the passage below:

Just as the boy retains the feelings that generate interactive pity in The Puppy, the erotic in this photograph is something too that is held back from us – something beyond what is seen and seeable, although this time the connection is the imagination of a sexually connective experience to which we are invited, though we never go there, never feel that jouissance: the absolute excellence of a being, body and soul together’. [4] We do, however, accept that this is an opportunity to fulfilled desire even though it must remain in fact the unfulfilled ‘kairos of desire’. Do you see that in this photograph? Does the exact placing and and half-gestural attitude of the hand invite?

The fact that here Barthes expresses his own sexual feeling for younger men and his desire that they interactively express their openness to his desire is the least interesting element of this scenario. However, it is still a vital aspect of the kind of connectivity that Barthes’ work still illustrates when we read it today so long after his early accidental death.

Perhaps we still need to ask what connects pity and erotic desire as effects of the punctum of photography. I think it is that both forms of embodied feeling tend not to self-satisfaction but mutual human awareness of the body as the site at the same time of mutual vulnerability and mutually elevated joy.

This message does not fit with the stereotype of Barthes I came across when I was young, who was, with Jacques Lacan and Michel Foucault, believed to be the friend only of the headily intellectual student not the lightly and heartily sentient student of human need and empathy with which I identified. Yet, for me at the time, a working class lad, still scared of French intellectuals and still attached to English traditions of thinking that I didn’t yet recognize as regressive politically like Leavis and the Scrutiny group, it was the open secret of the queerness of Foucault and Barthes that helped me, as did the targeted attack on binary thinking deeply at the heart of regressive thinking that still oppressed me and others by that heroic thinker, Lacan. They aided the escape from the misery of a closed up life. So let’s get back into ‘only connecting’. We owe it to dearest Morgan. Bye for now.

Of course, it all can sound quite mad, and madness does haunt Barthes Camera Lucida. But therein lies the other blog that I don’t intend to test myself by writing. Bye for now!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

________________________________________

[1[ Roland Barthes [trans. Richard Howard] (2000:3) Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography Vintage Classics Edition. The French text was first published in 1980, and Howard’s translation first published in 1981.

[2] ibid: 26f.

[3] ibid: 116

[4] ibid: 59

One thought on “‘Only connect’ said E.M. Forster but what madness results. This blog reflects on Roland Barthes [trans. Richard Howard] (2000) ‘Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography’.”