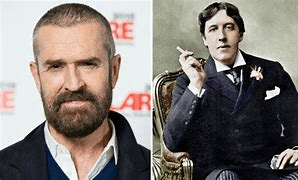

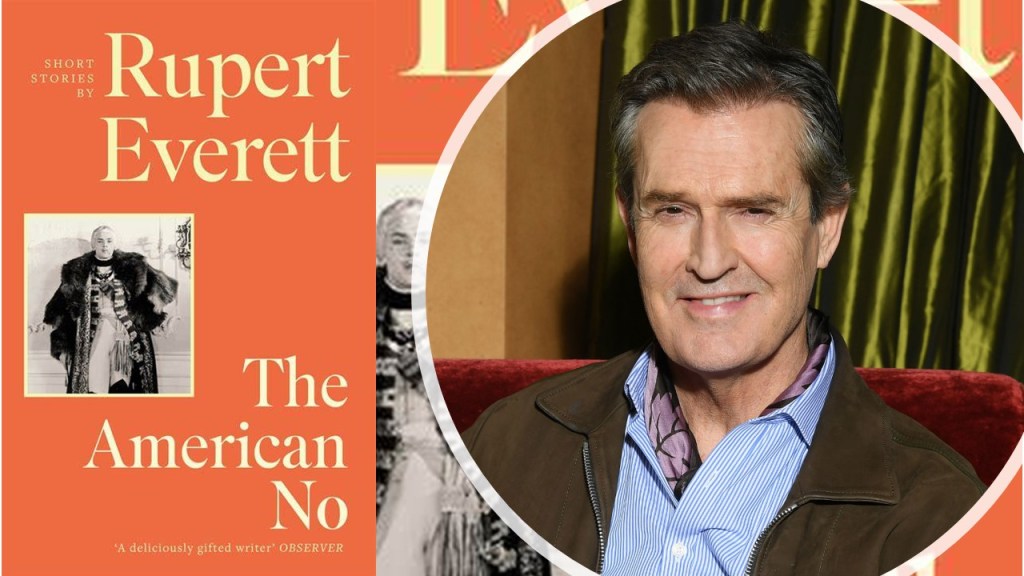

I decided never to rely on my very first impressions of what is likable or not. Why I persevered then with Rupert Everett’s (2025) short stories in The American No London, Abacus Books. This blog is mainly on his Oscar for A Last Season

The American No is a new set of short stories by the actor and filmmaker Rupert Everett, once famed mainly for his youthful beauty as a queer icon.

Now Everett is known as a maturely handsome man still able to create an effect as a film star but ambitious to be more fully engaged in film-making – directing, film-scripting and writing. These latter tendencies were not really enough to make me feel that his was a major writing talent nor one destined to queer classicism. This ought to have cemented, as it was when I first heard of the book, by a new set of short stories based on the concept of re-framing writing that had already been rejected, in the manner of an ‘American No’, which is where a prospective idea for a new film is feted and praised by film-making decision-making boards when ‘pitched’ as an idea or script and then ignored without further comment or even clearly articulated and rationalised rejection. This book is based on such ideas, which are now transformed into short stories.

The latter sentence is not entirely true because one story remains, as it was as a film-script. It is about Marcel Proust’s metamorphoses of male love-objects into men-like women (he refers here to Albertine – really all-through an Albert) called The End of Time (and published as the last piece in this book). That story really might have preferably stayed as a rejected bad idea, except that he had already written it by the time it was rejected (rightly I am frightened but ready to say). After all, it is no recommendation to any Proust lover that a scriptwriter really believes that: “there’s a lot of damned dull stuff in old Proust”, for as a queer writer, Proust’s ‘damned dull stuff’ about the passage of old cultures really matters even to his treatment of queer love (Everett’s play makes much of the sexual affair between Jupien and the Baron De Charlus a central plank). [1] And largely these stories, though fun in parts and with brilliantly written passages in others, do not make the case for an American (or any other nationality’s, massive ‘YES’.

Just a point about those brilliant short passages, though. they seem to come from deeply felt perceptions of the details of a culture that make for writing that transcends what surrounds it as much as the slightly disgusting and yet everyday thing it describes. In his Oscar Wilde story named after the alter-ego of a name he gave himself in Paris Sebastian Melmoth, to which I turn next after this diversion, he describes the staircase to the seedy hotel in which Wilde’s is staying:

The Alsace is one of a string of run-down hotels on a dirty-white street that runs between the boulevard and the river. there is gaslight and running water and cheap rates for permanent guests. … in the gloomy stairwell there’s a smell smell of cabbage and drains and the sound of a piano. [2]

This reflects another passage about a story called The Wrong Box set in modern Paris.

The perfume of every Parisian stairwell had its own particular allure. in the competition between polish and cabbage for the top note, in this case the vegetable was the victor. its cooked breath hung over the waxy parquet. … [3]

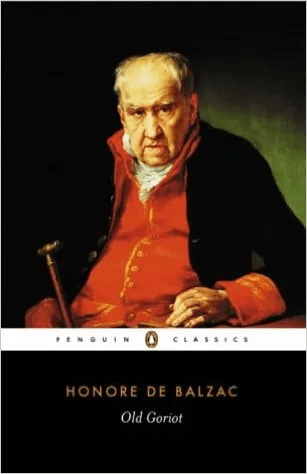

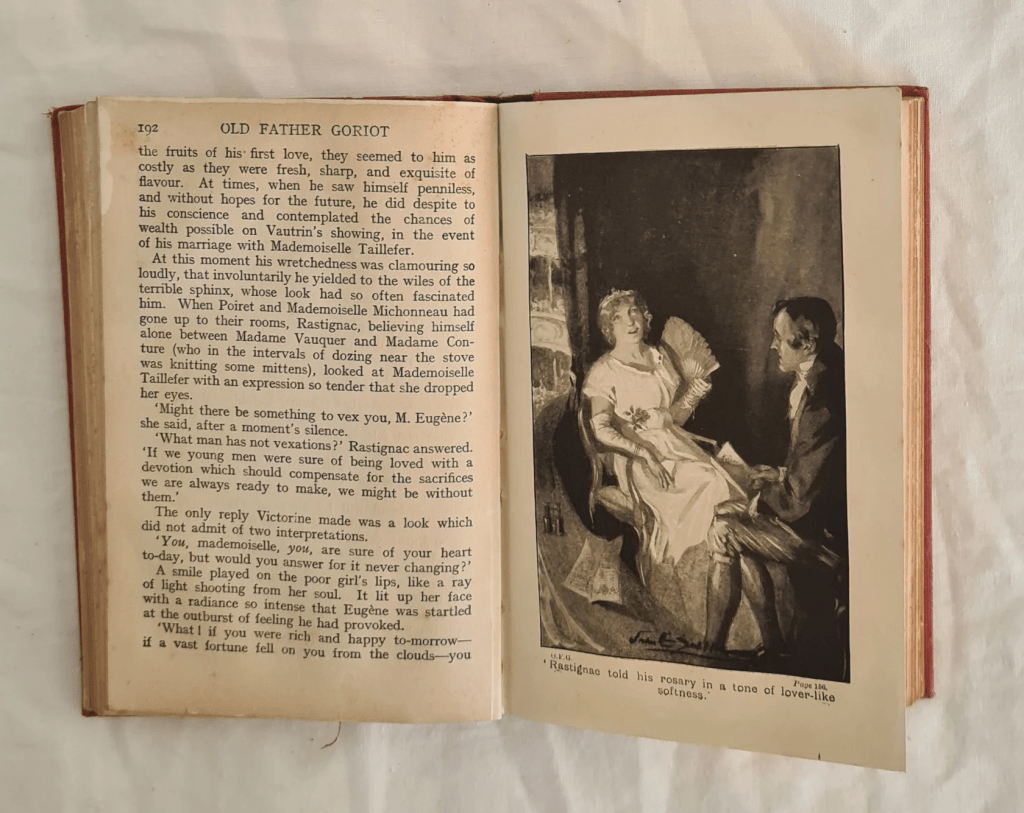

My first response to this, after noting the preference for the term ‘stairwell over ‘staircase’, indicative of American marketing preferences, was a moment of pleasure that immediately reminded me of a moment from Chapter 1 of Le Père Goriot (it is not necessary to translate the descriptive noun a ‘Father’, in French it is allowable to use this term as referring to an old man only, father or not – the ambiguity is in Balzac’s character and his circumstances).

Cette première pièce exhale une odeur sans nom dans la langue, et qu’il faudrait appeler l’odeur de pension. Elle sent le renfermé, le moisi, le rance; elle donne froid, elle est humide au nez, elle pénètre les vêtements; elle a le goût d’une salle où l’on a dîné ; elle pue le service, l’office, l’hospice. Peut-être pourrait-elle se décrire si Ton inventait un procédé pour évaluer les quantités élémentaires et nauséabondes qu’y jettent les atmosphères catarrhales et sui generis de chaque pensionnaire, jeune ou vieux. Eh bien, malgré ces plates horreurs, si vous le compariez à la salle à manger, qui lui est contiguë, vous trouveriez ce salon élégant et parfumé comme doit l’être un boudoir.

The first room exhales an odor for which there is no name in the language, and which should be called the odeur de pension. The damp atmosphere sends a chill through you as you breathe it; it has a stuffy, musty, and rancid quality; it permeates your clothing; after-dinner scents seem to be mingled in it with smells from the kitchen and scullery and the reek of a hospital. It might be possible to describe it if some one should discover a process by which to distil from the atmosphere all the nauseating elements with which it is charged by the catarrhal exhalations of every individual lodger, young or old. Yet, in spite of these stale horrors, the sitting-room is as charming and as delicately perfumed as a boudoir, when compared with the adjoining dining-room.

In that novel, the odour in the decaying pension, the odour of stale old bodies, of their breath and farts, owned by Mme Vaqueur becomes iconic of the odour de pension. It is integral to the novel – marks it in a way that matches both its realism and symbolism. Everett’s stairwell clearly too have characteristic odour de Paris ‘stairwell, in whatever century of Paris you descend into. This feels to me the mark of a significant prose writer who has not yet found a story significant enough to adorn with prose jewels like that, as Balzac very definitively had (but then he is Balzac).

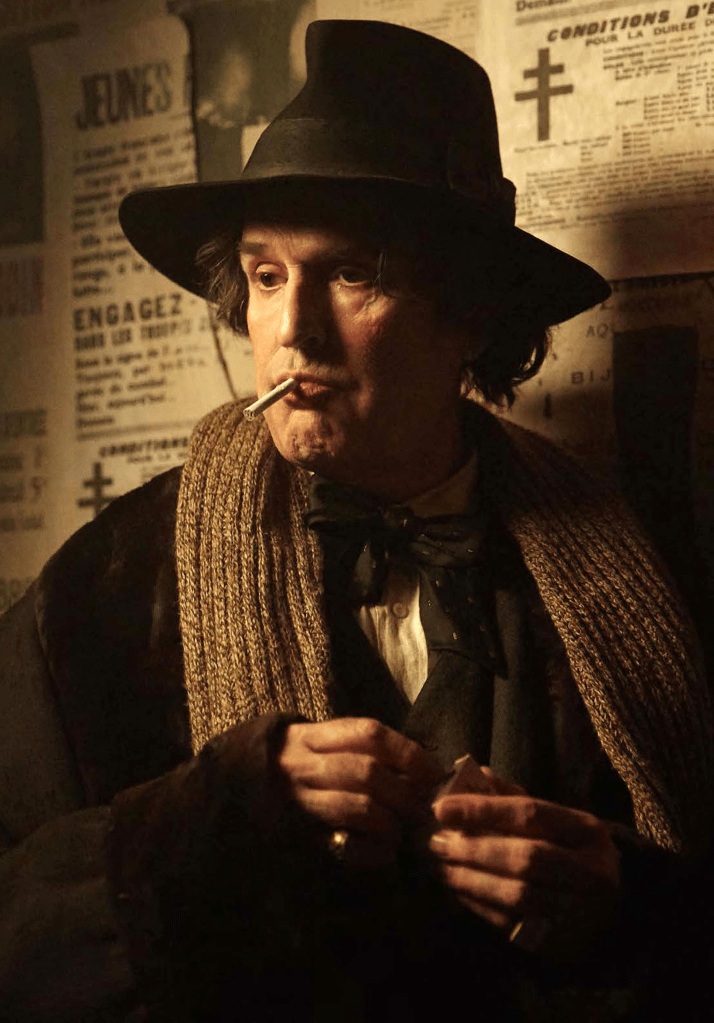

However, I want to turn to the story Sebastian Melmoth, which loved though, as I loved the film, The Happy Prince, whose story it mirrors if with more explicit attention to the sex with Johnny, a ‘street boy’ and prostitute. Both concern Oscar Wilde’s sordid but fantastical last days in Paris.

Most of the stories have a kind of prelude in which we learn why the story to be told matches the autobiographical and auto-psychological-analysis of Everett’s theme of the feel of rejection. This was needed because though the film of The Happy Prince was made, it was made only after a period of rejection of the idea when he was unable to produce or direct the film himself. And Everett has a case to make about how well or ill Wilde has been served by film-makers. Whereas each had their strengths, he says, all ‘seemed reverential’ and did not even try to capture what he calls ‘the weird magical destructive whole of that extraordinary character’. He lays his case on the line thus: ‘Oscar was a god, but also a wonderfully flawed fairy’. [4]

There is something awfully self-oppressive in a queer man nominating Wilde as a ‘flawed fairy’. The reference almost recalls the term ‘flawed hero’ used to describe the ambivalence of the protagonists of great tragedies by Aristotle, as if to emphasise that themes of some grandeur hang on the fate of this man, but themes that rely not only on the salvation of humanity, as with Oedipus and King Lear, as emphasised by the use of Aristotle to read both of the eponymous plays in critical history but the salvation of the common and everyday ‘fairy’, the queer man following his allotted fairy fate.And salvation (or indeed redemption is not the wrong word here, for the fuller quotation is:

Oscar was a god, but also a wonderfully flawed fairy. I think that it is what it means to be Christ. With his death the road to liberty was born. it had found a face.

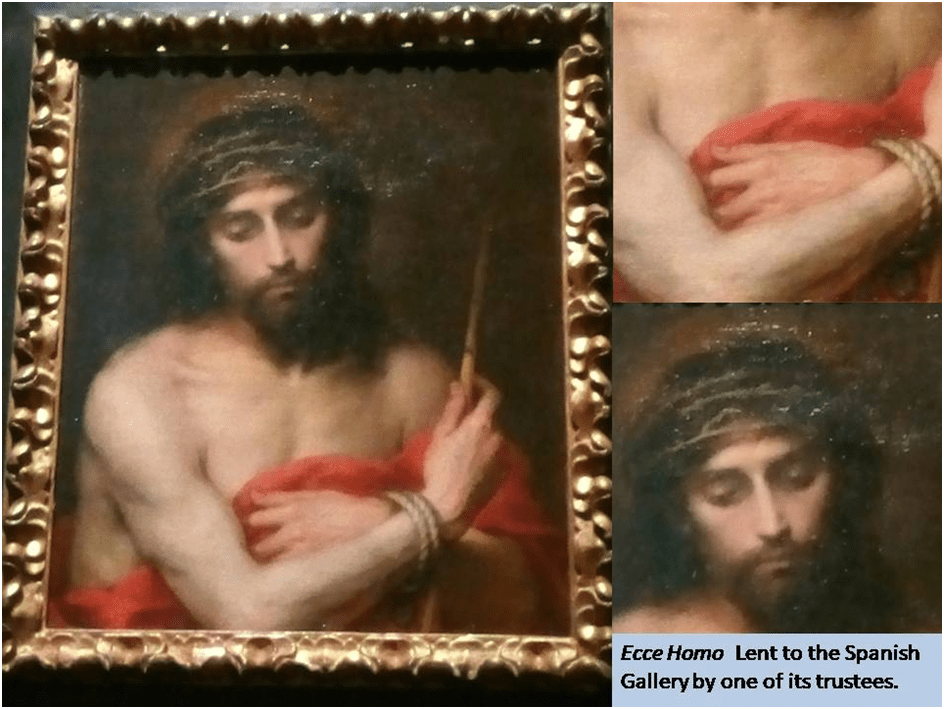

These words make the story into, as it were, a kind of queer version of the Ecce Homo tradition in painting and writing. I talked about this tradition in a blog at this link.

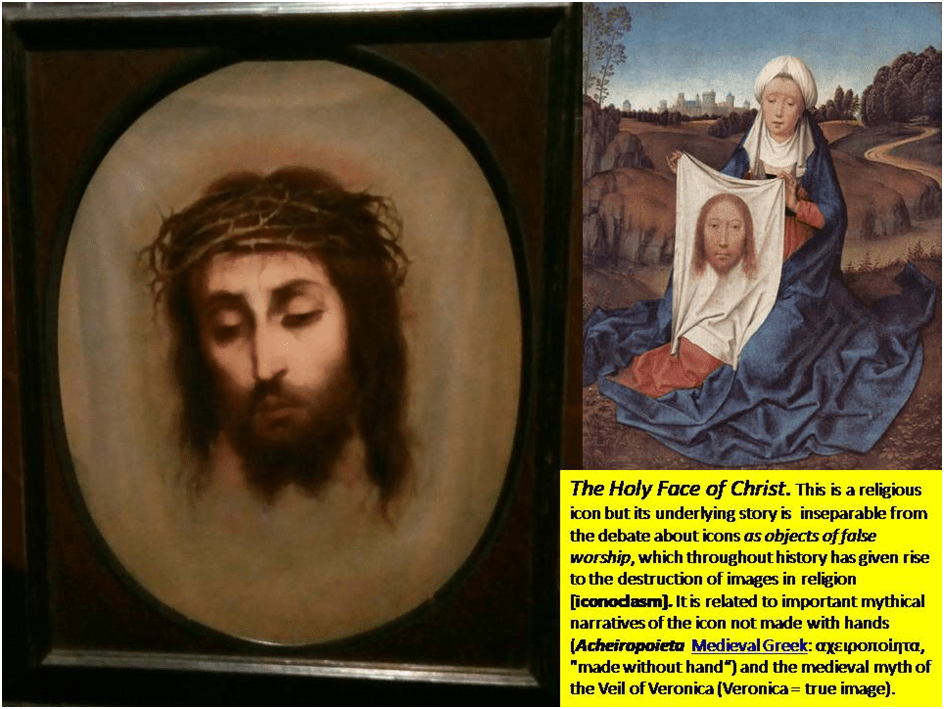

It is not unlike I say in the blog I refer to above the tradition of the Veronica paintings sometimes called ‘Behold That Face’.

Except this time the suffering Face has put on the look of camp defiance, even if a pose held against a background covered with the icon of the cross of Orthodox Christianity.

To redeem a fairy, I think Everett was correct to hint that, as with Christ’s mission, you had to redeem the flesh, and this story makes it clear that illustrating that point was Everett’s intention. In the first page of the story he setts up Wilde as the icon of the love-story of Cupid and Psyche (Psyche being the icon of the embodied self, only to then need to admit that for Wilde the fabulous chrysalis of his fairy’s romance (Psyche has wings too and is a butterfly) may be no more than ‘sucking some cock on a side street before the night is over’. For the fleshy face of Wilde is the cocoon that holds in memories, which have tended to degradation over his treatment under the law. Except that some memories come back that are redemptive – memories of his sons’ attic bedroom window in Tite Street, Chelsea , and him, in innocence, telling them from memory the story of The Happy Prince (read the story for yourself at the link), wherein an innocent swallow has to confront beneath him visions of London revealing ‘the suffering of men and women. There is no mystery as great as suffering’.

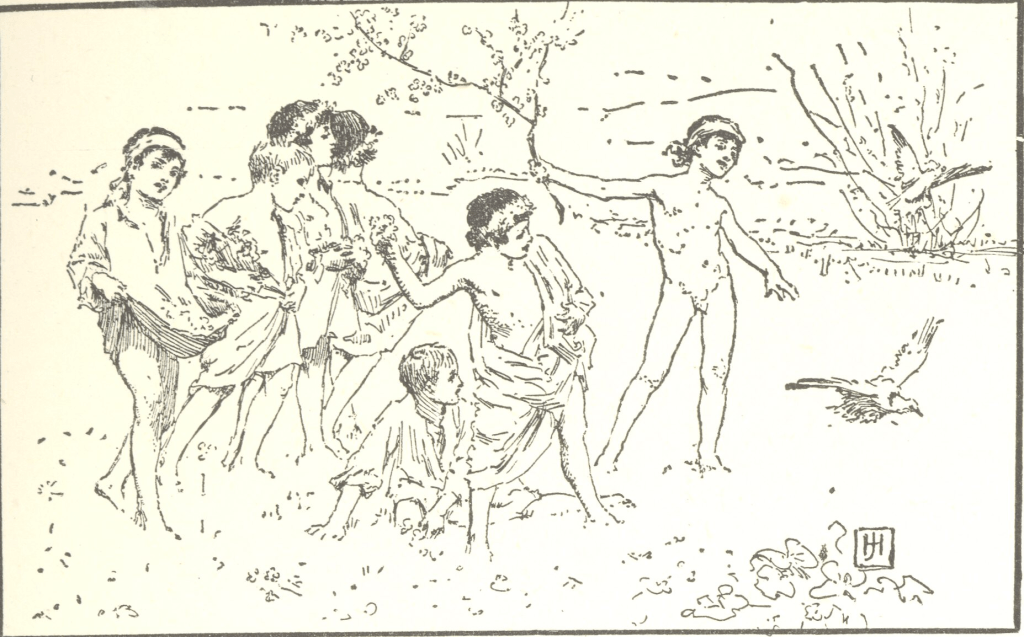

Everett cleverly ties down both the sentimentality of Wilde’s vision and his rather unreal but felt socialism to the body stuffed with the luxuries of privilege and being over-praised, for art that is funny but not so mysterious, told by the waving of plump bejeweled fingers and in a voice:’Sweeping the registers, seductive and fantastic, coming and going in great crashing waves’ This is writing of a high order – it nails Wilde on to a particularly appropriate cross, for him – that of a care for suffering human flesh that was sometimes flawed merely by having too much appetite for buying and consuming that flesh, sometimes regardless of any emotion to speak of than his own narcissism. This is conveyed in prose so wonderful, that if this were true of all these stories, I would think Everett a great writer without limiting my praise of the book as a whole as I have done above. Just as with Jacoomb-Hood’s wonderful illustrations for Wilde’s The Happy Prince, there is something flawed about the sexualisation of child flesh in the prose of Wilde’s children’s tales, precisely because it insists that it is innocent:

Illusration from The story of The Happy Prince

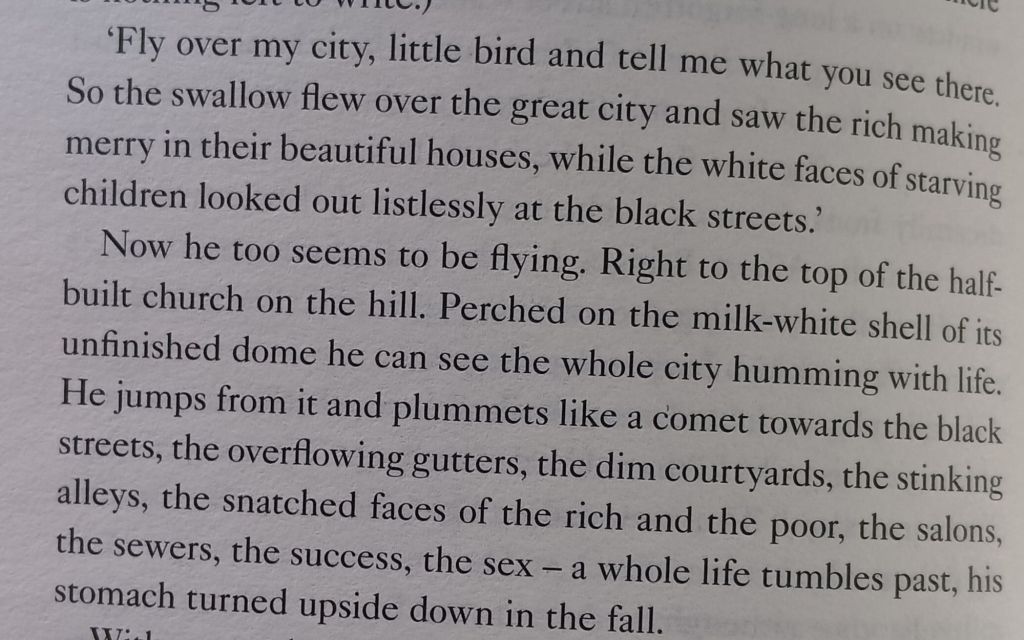

Here is Everett’s prose handling of a citation from that Wilde story – which runs throughout Sebastian Melmoth.

Rupert Everett (2025: 36) ‘Sebastian Melmoth’ in ibid: 33 – 55

Wilde’s prose that advertises its socialist response to economic degradation and inequality is exposed in the flight of Wilde imaginatively as he reads to his boys , but soon falls like Icarus – or Lucifer or Man in the story of the Christian FALL into places where dirt and poverty become, or have become synonymous with sex for Wilde, seeking it where payment eradicated distaste or ethics, even when the sex begins to seem exploitative on behalf of those able to afford to fly.

And this works into the structure of this story for this innocent memory of reading to his boys gets parodied later when Wilde reads a story in bed with both Johnny, the prostitute he has just had anal sex with and Johnny’s child-brother who had being waited outside (an hour he insists) until the sexual business was over.

“That was nearly an hour, ” the boy shrieks. “Story time”, He drags Oscar back to the bed and they jump aboard, to a screech of protesting bedsprings. “Everyone downstairs will be getting the wrong idea. now. where was I?” laughs the poet.

…

Johnny comes over to the bed, settles down carefully next to his little brother, stroking his hair, looking out of the window. [5]

If early passages turned innocence of intent into visions of the sordid in mixed memories, this beautiful moment turns the decidedly sordid in monetary terms int something innocent – where even the older youth experiences love of his brother, who has fled an orphanage, with the help of Oscar’s money and, it has to be said, his genuine capacity to give innocent pleasure to other men and boys. It is not long however before the trio are happily off to a dive bar for all, including the young boy, to be fed absinthe, whilst Wilde and a soldier called Maurice co-charm each other.

Wilde loves in the story to render sordid scenes into classical stories: Johnny is the beautiful Aninous to his Emperor Hadrian, yet when Wilde manages to get money (£5 – a lot then) from an Englishwomen in Paris appalled by his treatment by her husbands peers. When his alcoholism leads to a bad bleed , he soon compares himself to Marlowe’s Dr Faustus watching Christ’s blood ‘stream from the firmament’. However, soon beyond that he is soon with a ‘different set, wilder, dirtier’, and soon feeling too ‘the familiar creeping in his groin’, that points his vision to ‘a young man and a cadaverous child … the child is crying’. I think this brilliantly done. Even the pun on ‘wilder’ social sets (using the Wilde name as its base) is good. The story ends before Wilde dies though in the appropriate scene, where he pits his fate against that of the atrocious hotel wallpaper, by showing that the sexual abstinence his poverty caused him is precisely what his story saved many future queer men, Everett included from. The opun comes up again when he describes the effect of that abstinence as a circle of Dante’s Inferno:

I have had a very bad time lately, …, so had to wander about, filled with wild longings, trapped in the circle of the boulevards, one of the worst in the inferno.

Wild longings. Cue Emily Dickinson:

Wild nights - Wild nights!

Were I with thee

Wild nights should be

Our luxury!

Futile - the winds -

To a Heart in port -

Done with the Compass -

Done with the Chart!

Rowing in Eden -

Ah - the Sea!

Might I but moor - tonight -

In thee!

Of course, I have to repeat that not all of the stories fulfill as this does -some even rather distress in their language, as in the description in the Proust film-script of Marcel, who is introduced to a rat in a cage in a male brothel and ‘begins to masturbate inside his trouserrs., only for the boy to release the rat, such that:

Marcel, terrified, climbs onto the bed, screaming and coming at the same time.[6]

Well – maybe that is liberating too in art. Don’t see it myself! But for the Wilde story, I forgive Rupert everything!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

________________________________________________________

[1] Rupert Everett (2025: 238) ‘The End of Time’ in The American Now: Short Stories London, Abacus Books, 237 – 325.

[2] Rupert Everett (2025: 39) ‘Sebastian Melmoth’ in ibid: 33 – 55.

[3] Rupert Everett (2025: 21) ‘The Wrong Box’ in ibid: 13 – 30.

[4] Rupert Everett (2025: 33) ‘Sebastian Melmoth’ in ibid: 33 – 55.

[5] ibid: 44.

[6] Rupert Everett (2025: 324) ‘The End of Time’ in The American Now: Short Stories London, Abacus Books, 237 – 325.

LikeLike