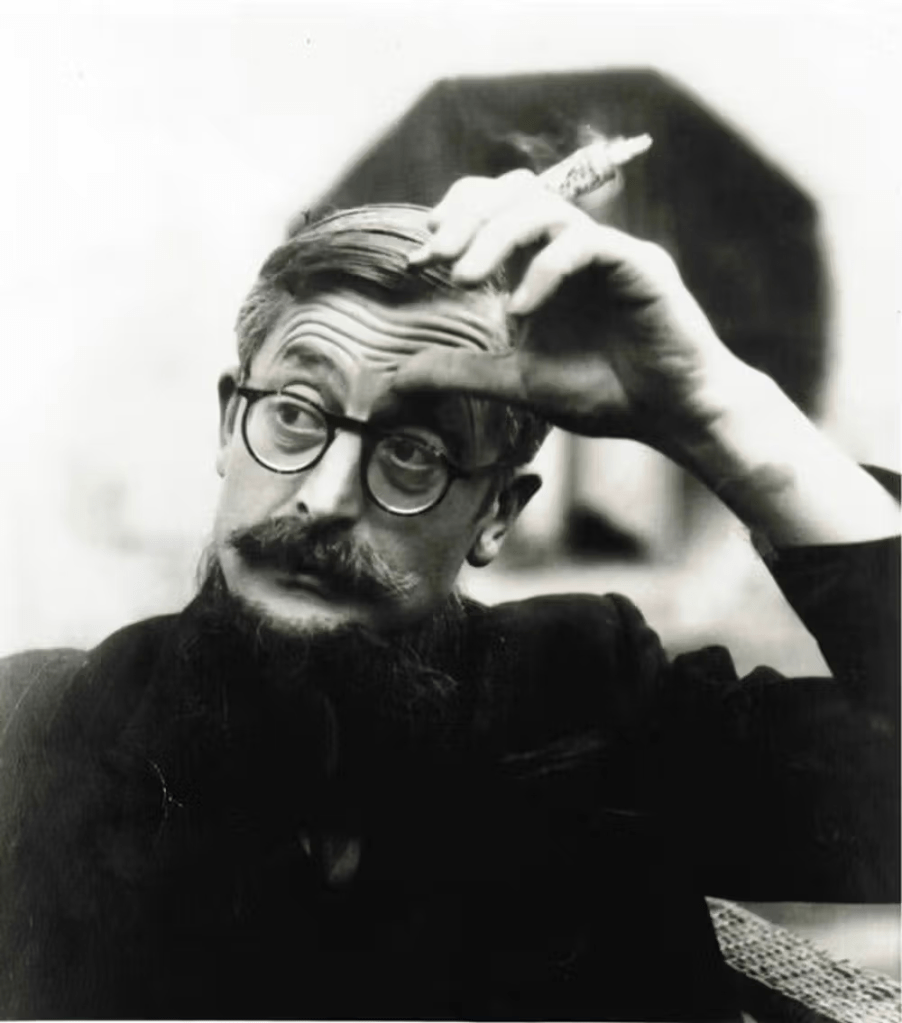

‘A taste for the poetry of William Empson may always have to be queer one’, or so spoke my thoughts as I get to cataloguing my few books (alas the critical texts – even the wondrous Milton’s God disappeared under an earlier cull, a misadvised one, of my library). Empson felt poetry was about emotion but emotion that struggled to escape sentimentality and did so by becoming faceted with ambiguities (Seven Types of Ambiguity or more). Thus, it had to be difficult to ensure that it reflected the complex realities of real emotional relationships and hence the quotation above. It was okay, after all, then to hate poetry that substituted easily acquired sentiments for tough, vigorous, and manly feelings. TS. Eliot had set the trend of such criticism. Vulgar critics, like Kingsley Amis, even applied it to Keats, as described in this delightful blog:

(Amis) begins by declaring that unlike the work of Milton, Shakespeare and Wordsworth, that of Keats needed no ‘glossary’; he appealed directly to the imagination of sensitive adolescents looking for a romantic alternative to the ‘ real world ‘. Keats believed in Beauty, which appealed to those under the cosh of exam pressures at school and the job interview. Moreover his tragic short life, ‘engaging personality ‘and ‘high aspirations ‘made him an ideal poet in the minds of the young.(1)

The idea here, let it be noted, is that good poetry needs work on its language, aided by a glossary – an idea akin to Empson’s. In his own poetry however he just wanted to get ‘readers to take more trouble over reading’. Yet he excepted certain sentiments from being inappropriate, such as DESPAIR at romantic loss but only under certain conditions. On writing on A.E. Housman’s later poems where the poet lamented the loss of any real ‘Shropshire lad’ in his sexual and romantic life, Empson diverts onto a defence of ‘despair’ poetry from charges of sentimentality under these certain conditions. I cite a note to the poem, that I will later discuss, in John Haffenden’s The Complete Poems Of Empson:

… there seems no decent ground for calling all Despair Poetry about love sentimental, … And granting the stuff can be good, it has a technical condition, whatever the personal background. It wants as its apparent theme a case of love with great practical obstacles, such as those of class and sex, because he despair has to seem sensible before this jump is made, and it is called universal work.

Sensible despair by the way is despair that is not wallowed in: the kind of stockpile feeling would have been different if (citing the same piece), ‘the man had been stronger’ and won his love or made a general truth of losing it. Thus, we loved Empson as a poet who looked for the emotion that is not merely the easy, soft bed of sentimentality.

In the midst of this abstract love of both critic and poet, I met him once by chance in a pub in Fitzrovia he used to frequent, and drink dry, with Dylan Thomas in the deep past. I got him invited to a literary event at UCL and visited him in his Hampstead home – once with his wife and son there, me with my then ‘girlfriend’, Cathy (before I came out): I remember his wife placing a large glass bell-jar over Empson’s head on that occasion to emphasis his rarity value. Empson retained a fluid sexuality throughout his life, though I have to say I would not have known this but for an incident when I visited him, ostensibly to see the ‘Autumn Tints’ (as he said in a now lost letter making the invitation) on Hampstead Heath.

Below is the poem Empson wrote on DESPAIR, with his self-conscious reference to the debate about easy sentimentality in such poetry:

Verse likes despair. Blame it on the beer

I have mislaid the torment and the fear.

The wonderful thing about those very lines is that it compares despairing love to a drug, like that takes the ‘torment and the fear’ of despair away, but insists that all drugs, even ‘beer’ in excess are as easy a mitigation as poetry. Empson had good reason to think beer a way of easing his inhibitions in all areas – having been disgraced twice for making passes at male taxi-drivers whilst under the influence. But enough: here the poem:

William Empson Success I have mislaid the torment and the fear. You should be praised for taking them away. Those that doubt drugs, let them doubt which was here. Well are they doubted for they turn out dear. I feed on flatness and am last to leave. Verse likes despair. Blame it on the beer I have mislaid the torment and the fear. All losses haunt us. It was a reprieve Made Dostoevsky talk out queer and clear. Those stay most haunting that most soon deceive And turn out no loss of the various Zoo The public spirits or the private play. Praised once for having taken these away What is it else then such a thing can do? Lose is Find with great marsh light like you. Those that doubt drugs, let them doubt which was here When this leaves the green afterlight of day. Nor they nor I know what we shall believe. You should be praised for taking them away. (3)

Dostoevsky was a writer who wrote queerly but in calling his talk after being reprieved from a death sentence for distributing anti-Government literature (in 1849) ‘queer and clear’, he is surely invoking the use of the word ‘queer’ current in his own day, as a slur but still used positively by some queer men even then. All Dostoevsky wrote was ‘Life is a gift, life is happiness, every minute can be an eternity of happiness’. (4) The reprieve Empson celebrates is from falling for a ‘marsh light’, a ‘will-o-the-wisp’, that might have drowned him but which in rejecting him saved him. Numerous young men filled that bill for Empson, as Haffenden shows in his great and massive biography of the poet. But that love is a ‘dug’ does not mean that a poem can not express complex feelings coming from it: ‘When this leaves the green afterlight of day’. The reading of Marvell’s The Garden (in Some Versions of Pastoral) seems to stand behind this lovely line where ‘leaving’ (as lovers do each other) suddenly evokes a true set of leaves with the last of the sun shining through them, like a promise of eternity.

But Empson in referring to the easy escape of alcoholism (no doubt in Dylan Thomas too) is also showing that the despair of a love lost because impossible (as he found the love of men, although in a sense they too could be preferred by him because they did not ask as high a price – marriage and all that – as women in his day) can reveal important truths generalisable to humanity. We shouldn’t just ‘doubt’ drugs’ even that of love, or use them to flatten our response, but understand that in life ‘Nor they nor I know what we shall believe’.

Empson is a tricksy poet but oh! such a missed one!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

______________________________________

(1) see https://jot101.com/2022/09/writers-born-a-hundred-years-ago-2-kingsley-amis-savages-john-keats/

(2) John Haffenden (2000: notes to page 80-81: 350f.) The Complete Poems Of William Empson London, The Penguin Press.

(3) see poem in ibid: 80

(4) cited ibid: 351

One thought on “The queer poetry of William Empson”