As I sort my library, I come across writers I have long meant to read. Such a one is the poet James Merrill, who I came across in relation to reading novels of his period some years ago. I know nothing really of Merrill. I read through the selection I have in the Everyman Library in which Langdon Hammer introduces him as potentially a ‘Mandarin poet’, deeply embedded in an exclusive culture and small circle of intellectuals that make the references in his poetry, to a small circle of people known to him, difficult to understand.

There was much in that idea that explains what it was that puzzled me on a first reading of the whole selection. When I feel that about a poet (which can be quite often for poetry is and I think should be a demanding read sometimes – as I say in the blog at this link), I usually look to read one poem more closely to give it chance to communicate . This is better I think than going for single or modish themes, though of course the only reason I bought the Merrill book was because he was a queer poet, whose masked poems were partly explained by that given fact of the homophobia of his,and our older poets’, times.

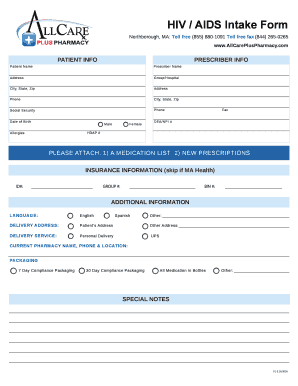

Hammer claims that we should begin to appreciate this poet because of his leaning out to themes of our own day. First, the dialogue with the oppression faced in queer lives and particularly by those who also had a HIV diagnosis. Merrill died of complications of AIDS, and his poems can be at their clearest when confronting ignorant prejudice, such as in some medical staff of his time like:

The nurse who thrust forms at you to sign,

Then flung away her tainted pen [1]

They can also deal with the fact that, to some degree, the foundation of an oppressive heterosexual attitude in relation to young people can be shared self-oppressively by queer men themselves. In one very funny poem, he looks at his and his male partner”s attitude to bringing up their dog, Cosmo, and finds evidence of binary heteronormativity therein. First he ‘accuses’ Cosmo of having ‘funny genes’:

Your grandfather

is known as One-Take Toby. There he stands

in the latest Life on his hind legs, tongue-happy,

spangled tutu, Hedda Hopper hat.[2]

Hedda Hopper, gossip columnist in a characteristic hat

Then, if that wasn’t enough, with that hint of queer cross-dressing in the gay dog’s family, he accuses Cosmo of aiming to copy his owners ‘closet behaviour’ in one of the many camp puns in the poetry:

Noticing your interest in our closets,

we exchange the eyes-to-heaven look of parents.

We want you to grow up to be All-Dog,

the way they wanted me me All-Boy.

...

Alpha males? That's what your other

Daddy and I must practice being - [3]

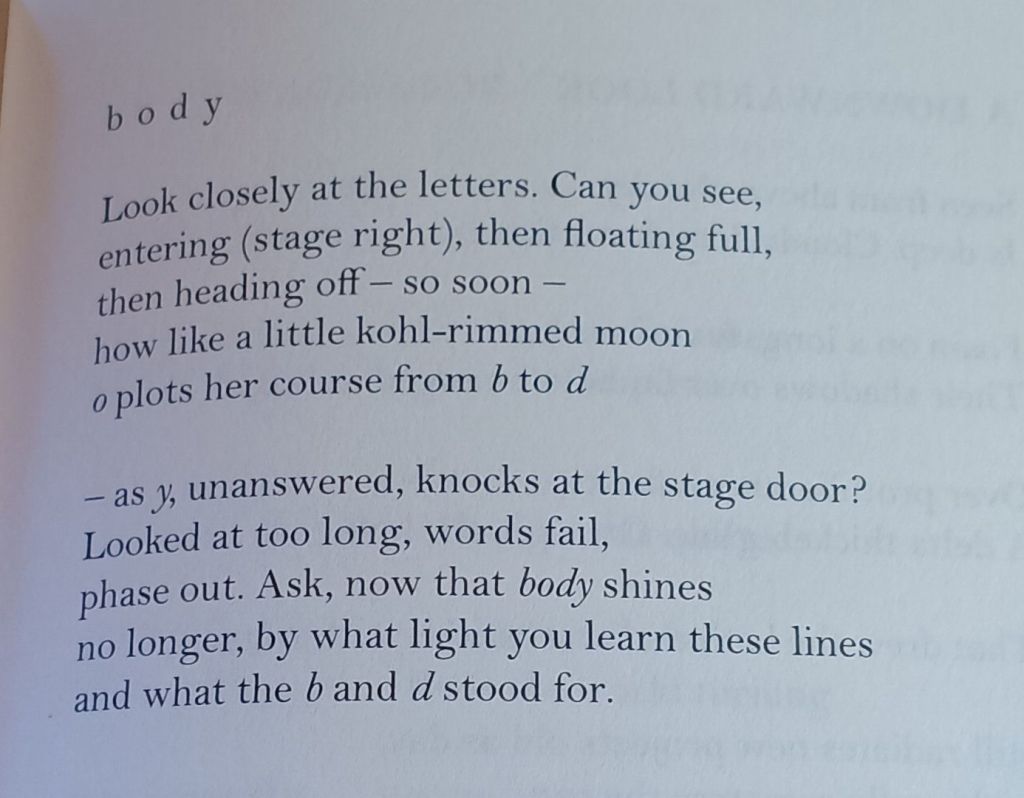

‘See,!’ Hammer might suggest, “he can write openly and with clarity about external issues!” And indeed we see that above in his self-satire on the persistence of the heteronormative or in the bitter attack on people like nurses who should know better than to be maintaining the stigma attached to HIV-AIDS. He does the same in the volume with other ‘single issues’: for instance, the destruction of communities by gentrification and ecological change globally, even in Greece where he lived later in his life. Sometimes he even turns his keen eye on his own process of dying from the complications of AIDS in poems that reach a kind of general truth about mortality, with his particular stamp on the constitution of meaning and feelings in words and the ability for them to mean specific things in their fragmentation into the constituent characters without which there could not be words, as in the beautiful brief poem b o d y.[4]

I could spend the same number of hours as my age in years parsing this beautiful poem, which seems to me a uniquely modern metaphysical poem, obsessed with deconstruction and associative contexts in competition. About birth and death (b and d), it explores the vacancy indicated at the centre of ‘o’ and shows that in a poem a body can both shine and then not shine, perhaps simultaneously but at last in the slippage of meanings across a poetic enjambment:

..... Ask, now that body shines

no longer

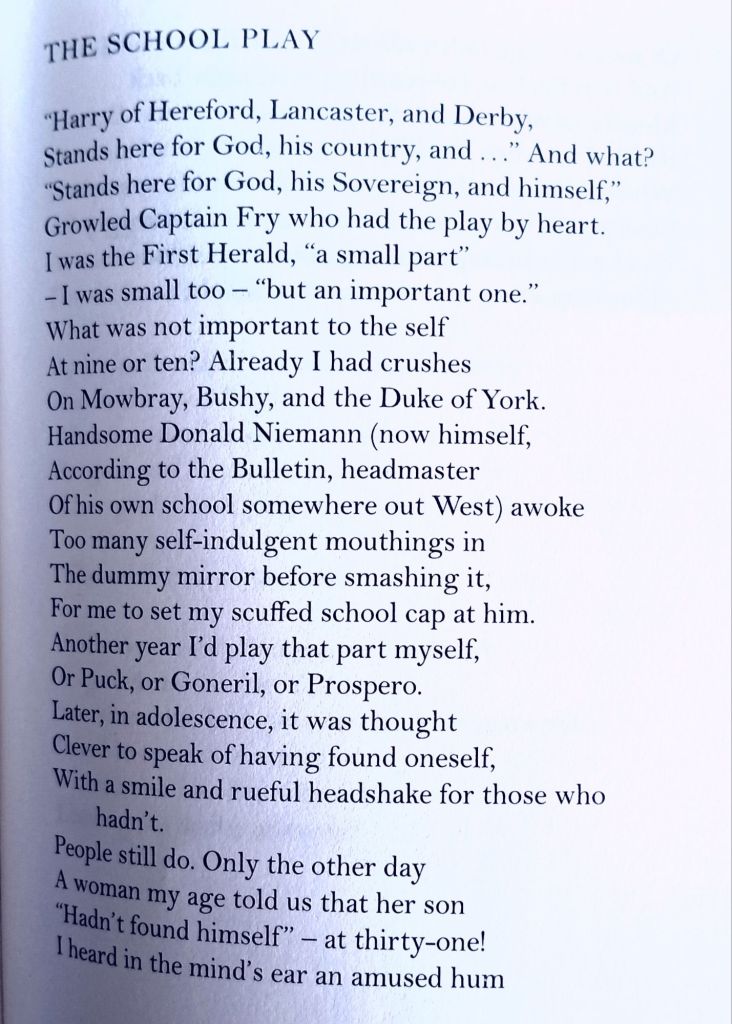

But I don’t have 72 hours to spare, so I will stick my first choice: Merrill’s poem School Play [5] . Here it is in full:

Hammer says in his introduction:

There is a disarming presumption of intimacy in his his tone, but it’s easy to feel excluded since we are not after all his friends. surely he must be speaking not to us but to some other audience of people as quick-witted and worldly as he … That impression diminishes, however, once we accept his invitation, get used to to reading his poetry, and recognize its recurring characters and locations, themes and motifs.

The issue of recurring characters, which occur most in the poems set in Greece relating to the family of the Greek male he had a later intense crush upon, and is more, i think, to do with the ‘presumption that the characters he refers to, even if only once (as in the Captain Fry mentioned here – clearly a teacher with an theatre-director flair and a passion for Shakespeare and boys). It is as if we all know Fry as a ‘type’ and are as familiar with this type as the need of all-boys schools to produce an annual school play in which one boy might play roles minor and major, natural or supernatural, and, male and female.

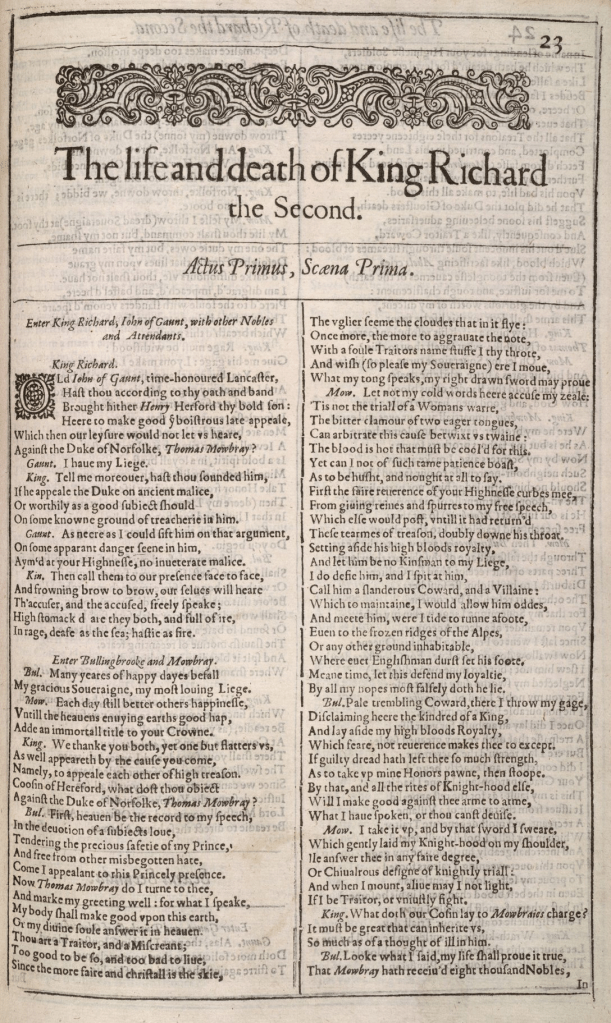

It is Fry, ‘who had the play by heart’ and who has this year cast Richard II (we are not told this we must recognise the characters and the lines cited from that play) with ‘Handsome Donald Niemann’ as, the aging Duke of York and, though he has a crush on Niemann (as also with the boys playing Bushy and Mowbray) and he (James Merrill), being ‘still small’, as the First Herald, a ‘small part’ to match his age-related stature.

There are compensations, Fry seems to says to James for playing this lowly role because ‘a small part’ can still be ‘an important one’. And anyway Fry, having the dispensation of prizes will cast James again in future school plays and he’d ‘play that part myself’, the Duke of York and perhaps that of the cynosure of younger boys’s eyes as older boys like Niemann are now of his, and others. but he’ll also play, perhaps, ‘Puck, Goneril or Prospero’, spirit, woman or authoritative fatherly sage respectively. At one level, the poem hints that the boys as a whole are the victims of their masters, who manipulate them to fit their sense of a fluid world where you can be anything you wish. I suppose when the world is definitively not such, such manipulation must be suspect as the end of the poem hints, as boys who are really ‘skinny nobodies’ (things without an adult body to speak of):

Emerged in beards and hose (or gowns and rouge)

Vivid with character, having put themselves

All unsuspecting into the masters' hands.

There is something chilling here in the motives of the ‘master’, something that is suspect and should be suspected, but there is another force in this complex poem. That force is the one that counteracts those social forces which limit in young people of any combination of the full range of differences across sex/gender domains (body / voice / genetics / social constructions) being labelled as having only one viable and acceptable identity – a self which is found only in supposed maturity by most, if not all, for which latter there was ‘a smile and rueful headshake for those who hadn’t’. Masters may have suspicious motives with the boys at the school, but the poemn insists surely that there is a moral equivalence with that behaviour in the binary heterormative rocess of becoming oneself, when that self is a ‘man’.

.... Only the other day

A woman my age told us that her son

"Hadn't found himself" - at thirty-one!

I hear in the mind's ear an amused hum

Of mothers and fathers from beyond the curtain,

And that flushed, far-reaching hour came back

Months of rehearsal in the gymnasium

Had led to: ....

This section of the poem turns on itself. After all boys become men by practising that role in the gymnasium – the classical model of that had long tentacles – and Merrill is pointing to how boys become socialised into male body forms. However as the sentence proceeds we realise he is not talking about the gymnasium not as the abstract concept of male training and rehearsal for manhood selves but the place where the school play Richard II was rehearsed (the play itself a tissue of contrasts about the acceptable and unacceptable in male sex/gender roles if not as radical as Marlowe’s Edward II, where the King is not just a soft man but queer with it (an open question in Richard II).

Of course mother’s worry that a son at thirty-one is not as he ‘should’ be! But is this not oppressive – certainly it is for queer men, who are suspected of the wishes that lead to them being ‘Vivid with character‘, and worse still made up with rouge. The poem is, after all, a poem about selves and the role of performance in that concept, and was so before Judith Butler wrote a word about those issues. The opening of the poem cites the First Herald’s lines from Act 1 Scene 3 of the play:

FIRST HERALD Harry of Hereford, Lancaster, and Derby Stands here for God, his sovereign, and himself, On pain to be found false and recreant, To prove the Duke of Norfolk, Thomas Mowbray, A traitor to his God, his king, and him, And dares him to set forward to the fight. Shakespeare 'Richard II' Act 1, Scene 3, lines 104ff.

In these lines the ‘real man’ in Richard II (not of course Richard II) is introduced as the model of a loyal Lord, loyal to God and ‘his sovereign’, who ought to be Richard II. Yet it will not be long before we realise that this same ‘Harry’ will become to stand out first as Henry Bolingbroke, with a claim (as he sees it) to Richard’s throne and role. He will also end the play as the usurper King Henry IV, prepared to take on Shakespeare plays under his own name, even if they are really about his equally Machiavellian son. The man – so much more a man (the play insists) than Richard II – deserves to be king and find himself as thus – authoritative male and father figure as he will represent himself.

In the poem, James realises his ‘small part’ is an important one because it first heralds (whether the embodied Herald knows it or not) that Harry Bolingbroke’s loyalties are unclear. In the ruse of representing young James requiring a prompt for his lines from Captain Fry, he singles out that the Herald in truth can and will undermine the mach will to power in Henry Bolingbroke, the Machiavelli (as he undoubtedly is):

"Harry of Hereford, Lancaster, and Derby Stands here for God, his sovereign, and ....". And what? "Stands here for God, his sovereign, and himself," Growled Captain Fry who had the play by heart.

Captain Fry, merely asserts his knowledge but young James has ripped the heart of Henry Bolingbroke and shown that his first duty is neither to God and his sovereign unless that personage, by assumed divine right, is “himself”. And thus it is, the poem suggests with all performance values wherein individual persons learn by ‘heart’ the part they must have (or so they feel) in the the world as it is currently after the ‘small part’ of a boy – the major part of a MAN, with all its ideological trappings, thought necessary to the adult male role scripted by heteronormative sexism, and indeed other norms. And why not the poem also suggests have not one man in min, even at that age but ‘crushes / On Mowbray, Bushy and the Duke of York’. We can see a similar theme in other half-dramatic poems in Merrill.

One such poem is based on an old Greek lover gone normative on him: Strato in Plaster. Read it, it’s a lovely poem about meeting again that bisexual friend who abandoned you for his sell-interest, and a lesson in not being judgmental or enacting the queer victim. [6]

Having lived with this poem all today a bit more fully I see what Hammer means: Merrill grows on you and you grow with him, to see the way his poems interrogate the deep structuring of everyday worlds and their normative authorities. Like Hammer, I will leave his Ouija board poems alone – for ghosts are really those past selves we left behind, as Merrill never quite left behind young James when he had a ‘small part’ when Mr Merrill now he has a larger one. hammer is right. This poetry is stuffed with innuendo. Shocking!!!! Lol.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

_______________________________________________

[1] James Merrill ‘Tony: Ending the Life‘ (2017: 244) in Langdon Hammer (Ed.) Merrill: Poems Everyman Library New York, Alfred A. Knopf, pp. 239 – 244.

{2] James Merrill ‘Cosmo‘ (2017: 221) in ibid: 221 -225.

[3] ibid: 222

[4] James Merrill ‘b o d y‘ in ibid: 245

[5] James Merrill ‘The School Play‘ in ibid: 163 – 164

[6] James Merrill ‘Strato in Plaster‘ in ibid: 121 – 124

One thought on “‘The School Play’: Growing up Queer amid so many manly performances. The poet James Merrill on the perils of a “small part”, “but an important one”, when: ‘What was not important to the self / At nine or ten’.”