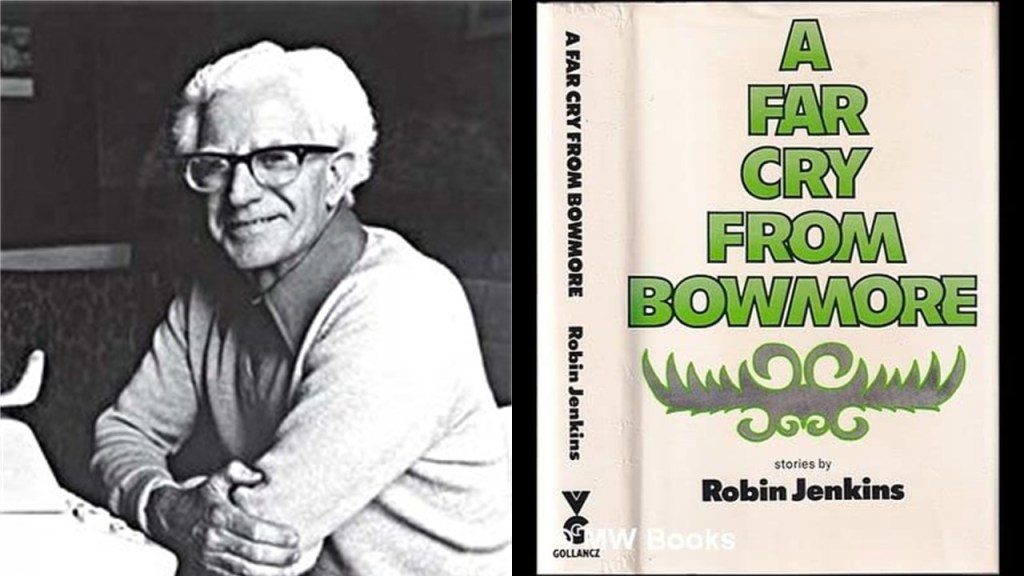

We sometimes think racism was inevitable in post-colonial Britain, but looking for evidence of it in writing is sometimes an issue that needs thought. I have a good, if incomplete collection of Robin Jenkins’ novels amongst my library which I once read avidly and all the time. I still prize above above many other novels of that period and others stories that I think could not be written ever in the same way again – novels difficult to penetrate and dealing with characters on the margins of what then was thought to be capable of representation or publicity. The Cone-Gatherers is such a novel (the ‘problem ‘queer novel’ of its generation in a way that D.H. Lawrence’s candidate novels like Women In Love couldn’t be) and, in many ways, a novel that remains a problem novel in the same way Measure for Measure is a ‘problem play’ by Shakespeare. His social-documentary novels like The Changeling still embody hurt and something more interesting about the moulding of character in nature and nurture interactively. His grap of the ways in which trauma embeds itself in the building of character is second to none.

Yet Jenkins lived, travelled, settled and wrote across a post-colonial world, which in British terms remained stuffed with expatriates ready to boast of having a grasp of the minds, bodily presentation and social manners of other ‘races’, which their ancestors once ruled and had unquestionable power over. An early short story of his, Bonny Chung published in A Far Cry from Bowmore & Other Stories (1973) is a case in point, for it contains an expatriate Scot, McGilvray, teaching in a college in the then Malaysia who very much represents the kind of denial of being racist that is the very sign of being very greatly racist. It emerges in a talk between men about what is or is not sexually attractive in a woman, discussing at first their colleague, Indian by birth, Madavi, whose story, in a suppressed and repressed way this noisy novel of male talk-over of women actually is. McGilvray denies his interest in Madavi despite Bonny Chung’s view that he is only pretending to dislike her, the more to monopolise her:

“… . You’re wrong Bonny. She’s too dark under the oxters for me.”

“Oxters?”

“Armpits.”

“Are you condessing to colour prejudice?”

“Aesthetic prejudice, more like. Come of it, bonny. you know damn well that in Asia the lighter the skin the more fortunate you’re considered. You won’t find an Asian beauty sunbathing on the beach.”

“that’s because Asian women have modesty.”

“No, it’s because though they’re already as black as tar they’re frightened they’ll get any blacker.”

“So you find Malavi repulsive because of her dark skin?”

Though he asked it scornfully Bonny at the same time was remembering how he himself had contemplated in horror wakening up in the morning and finding her black face beside his on the white pillow.

“Not repulsive. Just sexually unattractive. …” [1]

I shudder as I type that out. It bears every sign of the most potent, and potently denied, white British Racism, though discussed in the terms set by white middle-class hegemonic discourse of the time, as ‘colour prejudice’. The argument usually went thus – ‘Why accuse me of racism! Black people are racist too!’; with the usual reference at that point to the preference for lighter skin tones even amongst people associated with darker skin, especially South-East Asians. It was a difficult argument because such preferences could be evidenced, and later were in non-racist novels like those of Vikram Seth, especially A Suitable Boy, which discussed marriage choices by middle-class Asian women between different Asian boys, but it was of course a mask to the fact of the power and entitlement that White races insisted on retaining, long after their assumptions of right to govern colonies had yielded to realities.

Of course, the passage is repulsive too because it assumes the manner of entitlement men feel over the bodies of women irrespective of race, and I have no doubt that Jenkins intends us to feel that repulsive, irrespective of the race of the men involved. In fact. in this novella, both men become dominated by a white woman of incredible sexual power whom Bonny feels he is raped by, and who dismisses the sexual virtue of both, though McGilvray is more easily dismissed than Bonny, for she finds the latter, in her estimation of the sexual pleasure he yields her ‘not bad for a wee man’. The force of that veryvScottish evaluation of diminutiveness , ‘wee’, lingers because of its context.

But the other issue here is that this novel definitively paints these men as they are, and though it fails to tell us, by some authorial intrusion, that their attitudes are either or both silly and abhorrent in most respects, it conveys them as a good third-person narrator would by taking on their point-of-view without obviously judging it. However, the reminders of the limitations of the sexism, classism and racism of all the middle-class characters of all races is constantly there as a reminder that these characters are ethically, rather than ethnically, ‘little’ in moral stature, even when they aren’t physically – both white characters are horrors but very well-built ones, entitled by ownership of resources that have sustained them. Mary Parkhill, when she rapes Bonny is able to lift him and toss him onto her bed before mounting him. Bonny Chung is Mandarin Chinese, and his Mandarin roots are constantly evoked to stress his self, but yet again socially validated, superiority over others – women and men – in terms of culture, intelligence and taste. And, of course sexual cunning – the thing with which he tries to mediate his relationship with Madavi.. His moral superiority over others can be evoked, as it is secretly is with McGilvraty in the passage above, again, the passages that show this make for uncomfortable reading ans even more uncomfortable reproduction of their text. The Malayan ‘runner’, Masudai, who delivers the college’s internal post, is a case in point. The attitude that describes him is racist but is certainly racism reflected from the point of view of Bonny, not Jenkins as an omniscient narrator:

A native from a kampomg, he sometimes forgot his place. More than once Bonny had to rebuke him for his cheery impertinence.

That seems clearly to place what us described in Bonny’s perspective on it. So we should read the following, with disgust at the attitude but clarity that is being held up not as a model of describing what is but what thingsxseem in a mind structured by racist thought. Given the lettet Nasudai gives Boony backbto return, with comments, to sender, this follows. It shocks because it is not clear that it MUST be said from Bonny’s point of view:

Off went the thick-faced fellow with his jungle stride. [2]

No aspect of this relatively ‘simple’ sentence describes the character. The terms ‘thick-faced’ and jungle’ describe a stereotype of person that is one fed fat top-down from the social prejudices stored in the memory, with unfavourable moral judgements attached to them, of people trained to think their own racial type superior – in this case the Mandarin Chinese type with which bonny has been force-fed. It is all the more galling to such a type to be allocated to Division 3 in his housing rights in his Malaysian college when he believes he is by nature Division 1.

Bonny Chung himself, it has to be said, is an interesting but dangerous creation that could only have been created by a mind such as that of Robin Jenkins, that had passed through the training of white imperialist ideology and come out the other side of it scarred by prejudices which it is trying very hard to shed, whilst never fully escaping complicity with it as much as it would like. This describes Jenkins ‘ attitude to queer sexuality, as in The Cone-Gatherers, class, sex/gender, disability as well as race. Bonny is a man driven by sexual appetite but very much an idea of that appetite that constrains it as being appropriate only to men. Up to the present of the story, he has fed his his sexual self-concept from paid experience in brothels. It is, in his own conception, a sensitive sexual nature, which balances its practical and mercenary side with a view of himself as a ‘poet’. As a poet he could think sex sordid, whilst still aiming for it as his chief goal. He believes himsef passingly beautiful when he looks in a mirror, although marred by some racial self-oppression that just has to get both expressed and negated: he is he thinks ‘not only very handsome for an Asian but even better than that, he was , in appearance anyway, hopeful and innocent”. His self-concept is continually being undermined with contrasts to the race of Western European imperialists, that makes him on edge even when meeting ‘a big broad black-haired man in shorts, evidently a Scotsman from his accent and his uncouthness’. [3]

Yet McGilvray being a man is thought anyway a good portal to learning about potential exual experience available to him amongst the female college staff And there he hears of ‘Little Rosie’ guarded by a dragon-like sister, able ‘to chew your balls off and spit them in your face’. [4]

Private conversation nd inner thoughts are often as earthily expressed as that description of the virgin guarding dragon above. Domiciled in a cockroach-infested Division 3 dwelling Bonny feels sure he will attract to woman to feed his sex-drive for could a woman love any man enough to ‘put up with poverty and degradation’. He manages to bring three there but two escape and the third shows him too clearly that he despises that part of him that treasures above all his own sexual organ.

She was so greedy for it she treated him as he’d often treated whores. Afterwards he felt sure she could have described his cock better than his face; certainly she paid it more attention’. [5]

The novella continually exposes Bonny to the contradictory values with which he treats all women. He makes efforts to admire them for the status and idealised qualities but too often ends up amongst the pudenda. He thinks that this cannot contradict his sense of superiority of class and status as a poetical lover but we see here that when the boot is on the other foot, women who have an appetite for sex (the word Mary Parkhill will use to him to regard her liking for rugged men of size, for it was ‘obvious her interest was sexual’) he regards as sordid, their appetite as ‘greedy’.And yet he continues to think himself the equal only of women whose ‘capacity for love was inexhaustible’, who at a seaside party he can imagine able to ‘go down to the beach with every man there in turn’. [6] But when Mary Parkhill says lying naked under his body says “The gate’s open … Now gallop”, accompanying it witj giving ‘his buttocks a hard slap’ he feel.s ‘disgust and horror’ even at hiss skilled performance with Mary – and yet he gallops on so that he is not humiliated as a hard man that heh also wants to be. [7] Suddenly, when the sexual upper hand is a woman’s, sex without love is ‘sordid’.

The crux of the contradiction in Bonny is revealed in the complicated way he treats his own sexual appetite for the Hindu woman, Madavi. He is told she is a virgin, but he knows he is having an affair with a man soon to be married off by his parents in India to someone else. When he virtually rapes her, in her grief, following the wedding of her lover, he learns that she cannot be a virgin. He adores her supposed chastity and both wants to break it and find that she is dedicated to him on such a way that all her imagined sexual experience, which must be there simultaneously to her virginity, worships him like a god:

He remembered having read that in India once, before puritanism set in, there had been at every temple gorgeous creatures, so that man’s body might be assuaged as well as his soul. They must have looked, and smelled, like Madavi now’.

Dressed in red with exposed breasts, Madavi is the sum of all the myths he and his male associates have created around her. Yet she is in that so perfect because she is sexually passive herself- to be used by men, now using them to assuage her greedy hunger. Catatonic in gief, after giving way passively to sex with Bonny, she throws herself to her death from a high balcony. His role in that death is suppressed (he was, he says ‘writing a poem at the time’), but simultaneously Bonny suddenly realises that he is ‘only human after all’. As a result, even his awareness that McGilvray has no ‘stake’ in the death of a an Asian woman in tragic circumstances, makles him unable to drive home his awareness that this is because of thev Scot’s entitled white racism. But, in being human, in preference to being politically aware, he is as complicit as the Scot and will in the future ‘even boast about his part in Madavi’s death’. [8]

My own feeling about this book is that it challenges the very racism it can’t help but also parade, consciously in some of its characters- but unconsciously in its writing and willingness to repeat racist myths, from a point of view that is not explicitly critiqued. How I feel about this I do not know. Literature demands close reading. Does it always get it. And, if it doesn’t, are writers who challenge racism open to the outcome of being misread. I once really struggled with Tony Harrison’s V for that reason.

Bye for now

With love

STEVEN xxxxx

_____________________________________________

[1] Robin Jenkins (1973: 236) ‘Bonny Chung’ in A Far Cry From Bowmore London, Victor Gollancz, 167 – 252

[2] ibid: 227

[3] ibid: 177

[4] ibid: 179

[5] ibid: 193

[6] ibid 201f.

[7] ibid: 211

[8] ibid: 252