What is it to be confident? Usually mythologies are based around what ‘confidence’ should mean. The Viking sea captains and jarls of the Orkneyninga Saga are a strong subject for a literature in which boys dream of the men they might become but adolescence was a fraught and painful thing for George Mackay Brown (GMB), Maggie Fergusson tells us in her superlative life of the poet. GMB was always and forever called to prove himself as a man and poet, or so you might think from his prose writing.In his thirties he was the subject of concern in his family because he never married like his siblings and friends. Some felt that his lack of having anything like a serious relationship with a girl or woman before then had something to do with his sexuality. In his autobiography, which he never wished to be published, he says, as cited by his fabulous biographer in her interpretation of his complex sexuality self-representation, that this was not because he was ‘homosexual’:

“I had no homosexual urges, apart from one, when I admired another older schoolboy in my class, and for a while couldn’t have enough of his company and his talk … This infatuation lasted for part of one summer, then broke like a bubble.” It was simply, he says, that “I never fell in love with anybody, and no woman ever fell in love with me. I used to wonder about this gap in my experience, but it never unduly worried me.” [1]

Fergusson has her doubts about how well the poet assessed the amatory condition of himself and others. The issue however, seems to ne, as she says somewhere else in her book, that his sexuality usually was described in a way that matched the preconceptions of others. He was confidently thought to be gay by his later close friends. Kulgin Duval and partner Colin Hamilton. The queer poet Edwin Morgan agreed with them, though felt that his sexuality was constrained by his preference to lonely imagination and the work that might spring from that. Yet there is intimacy in his letters to women later, notably to Stella Cartwright.

Other women attest to his ability to profess, if mainly from a distance, statements akin to professions of heterosexual love. His Catholic friends thought, in contrast to both other sets of friends, that he was drawn to monastic celibacy. Fergussonn says of all this that they were ‘all, in a sense, right’: :all seeing aspects of a truth that George himself never fully entangled’. [2] During the time after finishing Vinland the poet Sheenagh Pugh described him as ‘flirtatious’ too her but also insisted that underneath the warmth he performed in her presence that she, nor anyone else (man or woman) would ever ‘get closer than he wanted you to, which would not be very close’. [3]

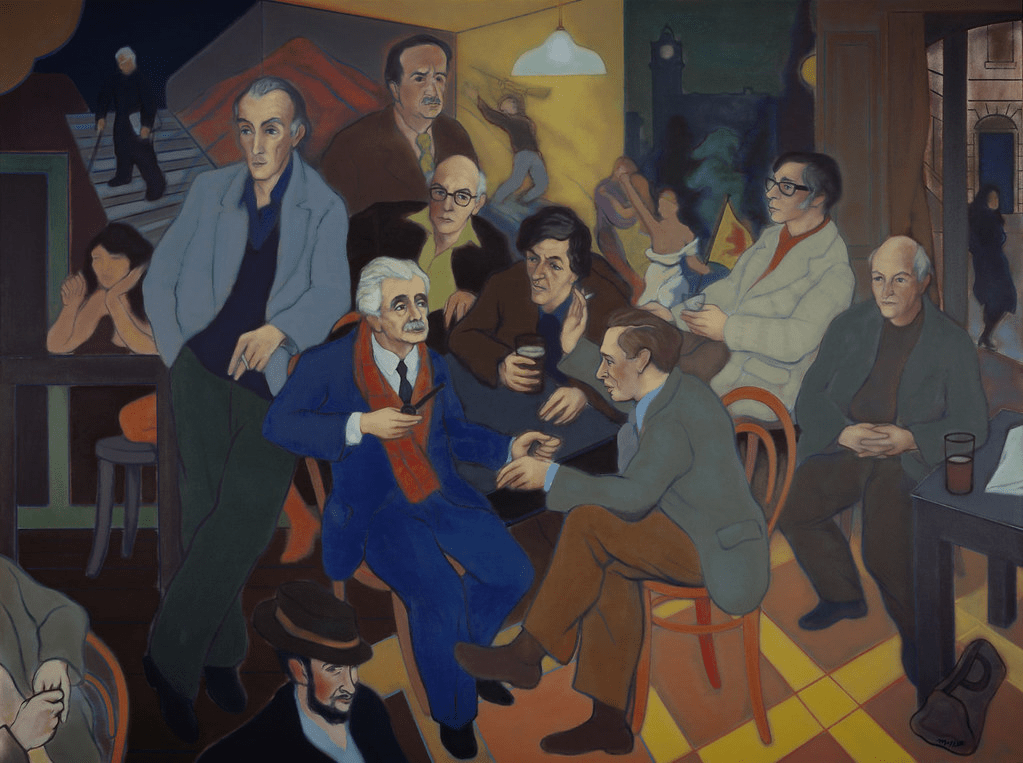

GMB’s hand edges towards that of Hugh MacDiarmid in Moffat’s Poets’ Pub. GMB is centre with thick black hair.

To be have no sexual certainty, even a consistently asexual one, if I think what qualifies us to describe Mackay Brown as confident in his queerness, his chosen oddity from expected norms that could comprehend a range of beliefs about his sexual nature whilst not embracing any one of them, even perhaps in imagination. in imagination, of course, one can embrace many of them, though always with distance. Yet in Vinland, in which Brown imagines many types of relationship, though none, other than heterosexual generation of children is ever evidenced and heterosexual symbolic union only once, when the hero Ranald leaves behind his adolescence in marriage to Ragna, though even her the union is seen as a ritual giving up of the more pleasing company of other young men. Ranald only ever writes one poem. It is for his marriage and ends with Ranald speechless imagining a ‘song that can never be uttered’, and the heard and uttersd song is not to Ragna but named The Summer of Young Men: its best lines imaging that summer as:

A thousand glittering pieces.

Richer than jarl or prince

We were the young men, unwithering always'

Hallvard returned laughing.

Bright from "the mermaid lair", with two lobsters.

Fell on my hand, soon,

From the tree in the hall garden

One dry tarnished leaf. [4]

Call me consumed by wishful thinking but the confusions of sex / gender that surround a ‘mermaid lair’ seem to infuse themselves into the inverse syntax of the sentence that starts with the verb, ‘fell’, that leaves a hint of the young man, his lobsters and all, falling into the poet’s hand, rather than the ‘dry tarnished leaf’ that falls there in reality in the working out of the sentence, with its subject at its end. The poem works because there is close touch invoked, but the culture of the novel resists such touch, even amongst families. When Ragna is reunited after many years with a son she has lost and thinks may be dead – although instead he has become a ‘poet’ or bard, she not unsurprisingly ‘kissed’ him there and then in front of the whole company with whom he arrives and the rest of the family. There follows this strange sentence: ‘This was thought to be too extravagant a show of affection’. The suppression of agency in sentences without a subject is always troublesome in reportage but here it is troubling because we cannot easily see to whom this closeness and intimacy is seen as ‘extravagant’. Certainly it is by Ragna’s daughter, Solveig, who only ‘shook him firmly, but still coldly, by the hand’, and the embarrassed ‘farmworkers’ who ‘shuffled their feet’. It may even be the narrator, although the narrative rather plays this scene for comic rather than embarrassed effect or an attempt at ‘cool’. [5]

Stromness: GMB lived near the harbour pier

It would seem to me that this playing at games around the display rules of affection and love in cultures is Mackay Brown registering the queerness of human inter-communion and community, a queerness hat comprehended his own questioning uncertainties underlying his denial of any label. It has everything to do with the representation of masculinity and the preponderance of interest in its nature. Vinland is its novel, not least because it invokes the cultural authority of the sagas of Orkney, even down to the favoured hero of Brown, King (or Saint) Magnus, who appears in this novel as well as in one named after him by Brown, and whose chief asset was martyrdom to the Christian and Catholic cause.

The men of the Orkneyinga Saga prove that they are men by perilous travel, by seeking power and control over other men and their lands, as well as over nature itself – whether the nature of land, sea or of flora and fauna. They imagine themselves in relation to the vastness of the country or countries they rule over and in their resistance to any softness in their behaviour of that of others persons (inevitably oe eventually of all whom become their rivals), things and places that might cause them not to struggle to control rather than to become passive to and introject that softness. When near the end of his career Brown wrote his own version of the saga stories, he ensures we know its significance as a story of transition from the military violence of the plundering economy of the Vikings to a world dominated by the passage, not of of marauding thieves from other nations and peoples and their ships, and even sometimes colonisation of those lands, or part of them,. The telling thing socio-politically about the novel is that it dramatises the refusal of Leif Ericson (sic) to see absolute good in the colonisation of the Americas (which Vinland will eventually be) even though he twice considers it opportune. Vinland may not be paradise (an idea that runs through the book) whilst the constant comparison made itself is earnest that Vinland is more like paradise the the worlds of Scandinavia, Scotland and Ireland. [6] Ericson says that ‘Vinlanders had entered into a kind of sacred bond with all the creatures, and there was fruitful exchange between them, both in matters of life and death’. [7]

In my reading I think the sense of fruitful exchange between all ‘creatures’ with each other applies to psycho-sexual-and-gendered natures too, for in the novel there are many, as there are many variants in particular about how men and women relate to each other within their sex-gender category as between the# sex-gender categories. Solveig is a wonderful case in point in the representation of the cold woman, better in what are conventionally men’s roles in the societies depicted in the novel. Of the actual variations of masculine and masculine affection there are many.

The notion of a natural bond between father and son is itself broken. Ranald Sigmundson has little or no relation to father Sigmund Firemouth, fearsome to both his wife Ragna and son, and from whom Ranald Sigmundson flees to end up as a stowaway in the boat of Ericson. Boys taken up by men older themselves replicate biological son-father relationships without being them, and use this gap of difference to vary the types of inter-masculine attachments found. In his longship Ericson keeps Ranald near ‘seated beside him’ while he teaches him about the way the world’s categories shift more than might be thought. Men under the influence of the moon (long considered a feminine deity) become different and it does so by, despite its actual distance, coming into close proximity and touching us:

Does the moon touch some pulse in the blood? I have noticed that the moods of seamen alter with the changing moon. Many a sane sober man says strange things under a full moon. I have known men of few words utter poetry at such a time.

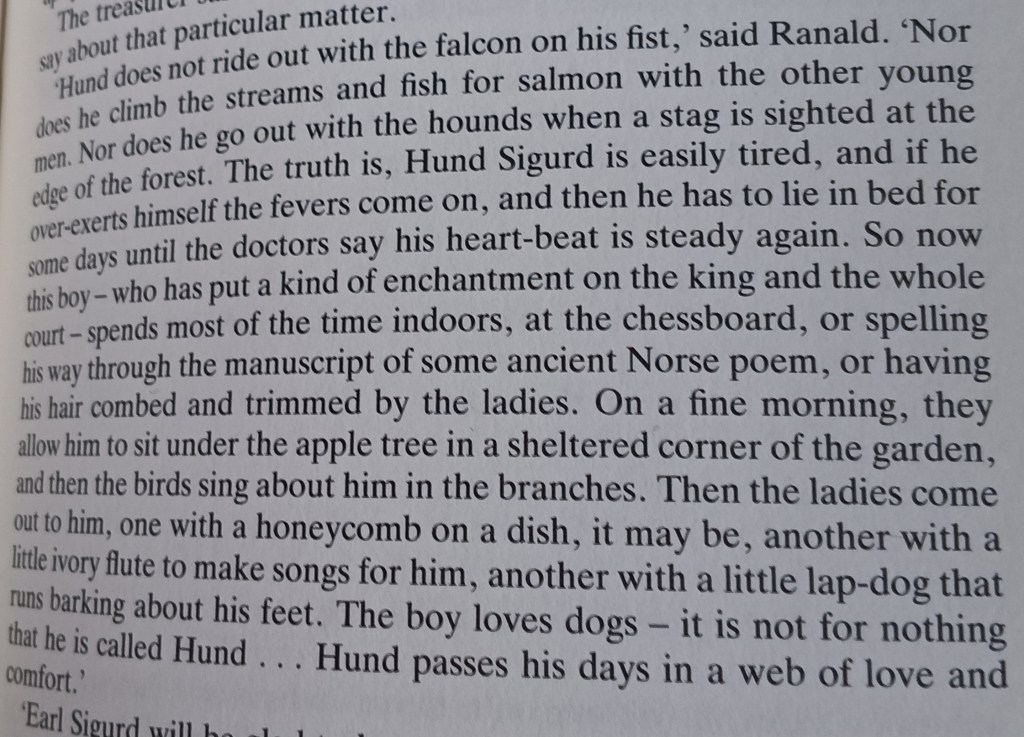

Men play the father boys who are not their sons but do with some over-plus of love. This applies to jarls too. The Earl Sigurd has especial love for his don, Hund. But so too has King Olaf of Norway who keeps Hund by his side, with Hund’s ready agreement and pets him. The relationship is not that of Ericson and Ranald but is definitely a variation thereof. It matters because Hund will and does not fit the stereotype of the male prince. he is sickly in body and will soon die. Sickly boys may however be a means of symbolising one version of how male difference is registered. Hund is cossetted, associated with women and female pursuits not male ones (in their heteronormative and sexist distribution) – his love of dogs is not for hunting but petting. Later in the novel, his elder brother will in the end meet his death (at the hands of yet another younger brother, partly as a result of having inappropriate affection for a ‘lapdog’ (and yes the excuse for a dog gets it too – stabbed through by male brutes).

My photograph from George Mackay Brown (1992: 65) Vinland London, John Murray.

The boy with its ‘femme’ ways has nevertheless ‘put a kind of enchantment on’ King Olaf. To live in a ‘web of love and comfort’ is like a spider’s web, another trap for ‘sissy boys’ as GMB sometimes felt he was, no better than the difficult role of playing the man defended by the stone of his masculine defences which too for m a web, but a stone one- as in one of two most beautiful poems by Arnor, who will eventually be recognised as Ragna’s son, herself a rather hard nut:

Can the runes of verse

Celebrate victory, and restore

A broken stone web. [9]

After the death of Hund, King Olaf mourns him, as does his biological father, Sigurd. But Olaf soon )in the time-scale of this novel at least) gets himself son-of-another man to pet, the same who will adopt a lapdog. Both men and women change. When Thora, Ranald’s mother, is first introduced to us, it is described as ‘normal;ly, ‘a quiet woman’. But norms change – even those of sex/gender. In this novel this is sometimes plotted through the tendency of weeping to be confined JUST to women and children. The Lady Eithne, an Irish queen, detests the ‘modern’ softening of men. To die young, and preferably in battle is best; and to death she sends her son Sigurd, recommending it also to Ranald to court Death wherein whose halls: ‘You are young forever’. [9]

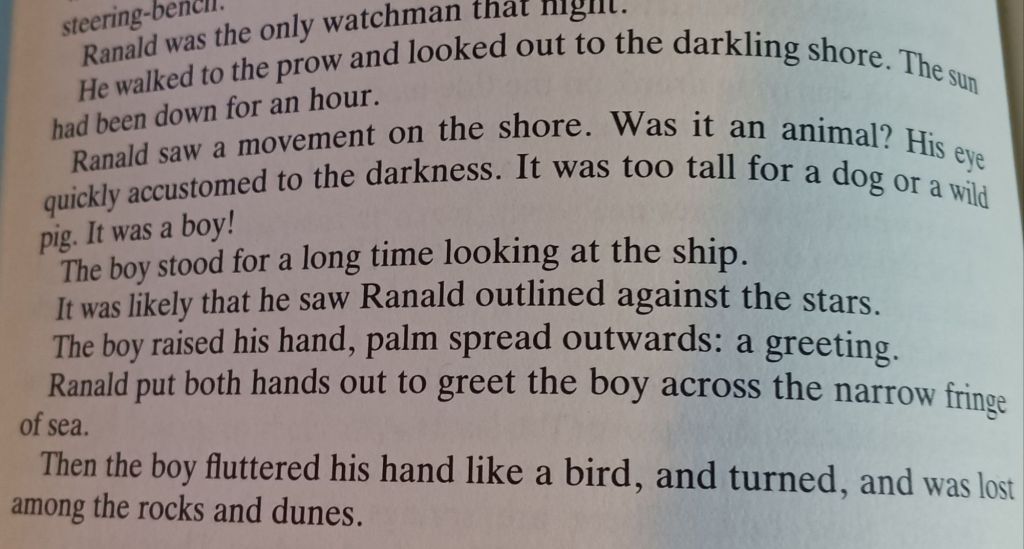

But none of this would matter but for the awful longing that Ranald feels, as an old man to sail to Vinland again and meet the young male Vinlander, a Native American with skin of a red hue he meets early in the novel and ‘make his peace’ with him – without even noting that that the boy would now be an old man too by now. [10] There is somewhat of allegory in Ranald’s first meeting with the boy. It is at a distance but it mimes proximate touch of their hands which flutter like birds (another potent symbol in the novel), and has the air of romance:

ibid:: 12

The ‘darkling shore’ is a Keatsian touch, as is the emergence of a ‘boy’ from muddled expectations awaiting lots of other creatures. The whole attitude is that of the lover awaiting the realisation of his love-object, and though the distance between the boys (this I think the only love scene between two males of the same age) is actually great – the ship Ranald stands on is floating – perspective turns it into the ‘narrow fringe of the sea’. What starts as a signal becomes almost an embrace.

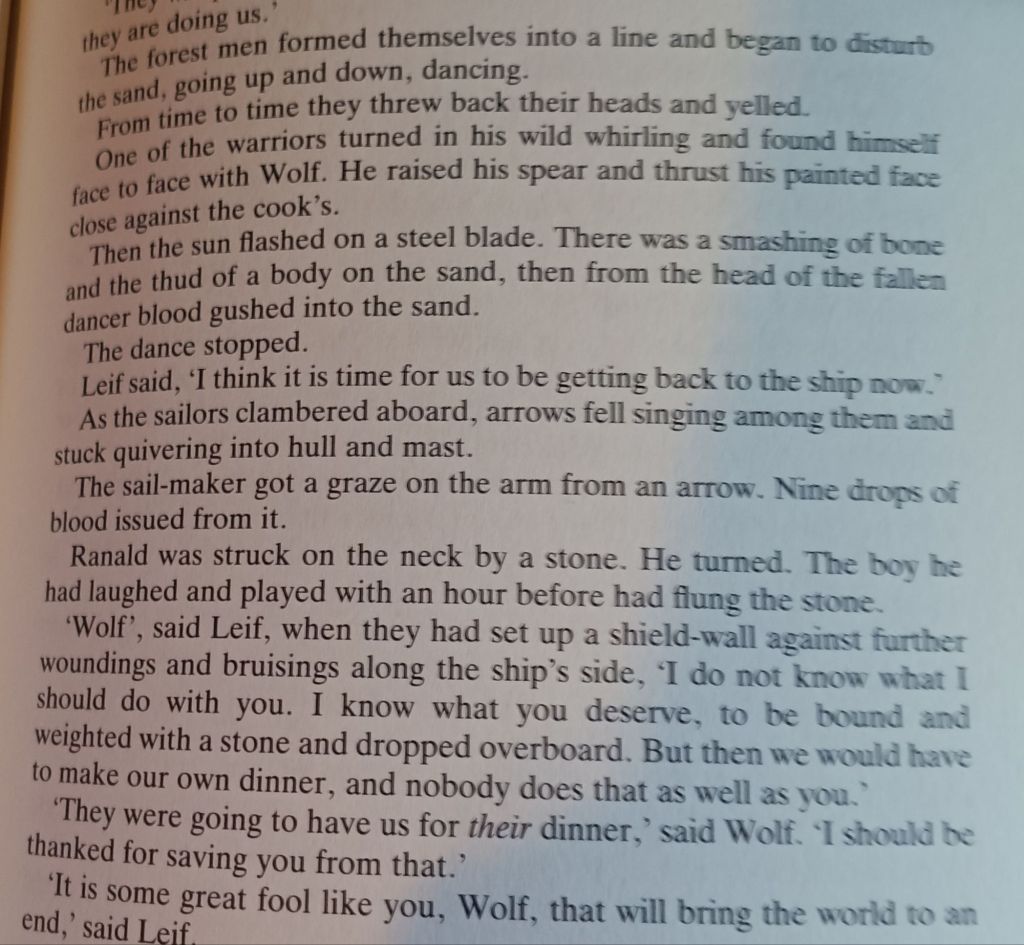

But the contact never comes. The two ‘races’ meet on the shore and exchange gifts – the Vinlanders wholesome ones, the Scandinavians alcohol (allegorical of later relations between native and settler Americans). The Vinlanders become drunk on ale to which they are unaccustomed. They dance their own cultural dance but at one point frighten the Scandinavian men. How? They come too close – men’s faces nearly touch and the Scandiavian man named Wolf cuts of the head of the ‘brave’ which has come too proximate:

Ibid: 15

And Wolf’s hastening of the end of a world leads to the burgeoning feeling between the two boys to become to cross the duistance between them not with embraces and waves but with sharp-edged stones that wound. Mackay Brown renders this all with humour, making it all the more poignant to me: memorable until the time when the old dying Ranald will want to return to make his piece 215 pages later.

Among the many types of thing men can be are two poets: one named Ard, who fails to build community in Vinland by staying on the ship, and who fails in generosity as a poet, becoming alienated from the community,the other is Ranald’s errant son, who becomes by fleeing his parents as Ranald did, a poet called Arnor, whose finest song describes the wolf and the eagle who might have killed and eaten him as mourning his potential, although he is lost: ‘O sweetly his eye looked on the light of an April morning’.[11]

There is something about being a man that deserves the fragmentation of its ideological types and its recofiguration in a new relation to the animals and the land – not exploitative of the latter but definitive of a human-animal-plant-and-ecology defined community. And this will not divide love into categories surely. I think Mackay Brown choose asexuality as his sexual expression but only because it was the only queerness to the norm that he could realise outside his imagination.

At this novel’s opening the sailors on the West Seeker, Leif Ericson’s longship, form a community of men. It is not viable Ericson tells them. They will need to return home to find women to join them in order to colonise land they merely now settle for the moment, but there is a kind of dream behind this community – or at least, to my ears, Mackay Brown writes it thus, making of it the boy’s dream that Leif offers it as to him: ‘I know this, that boys love to range freely in the country of their imagination, and there they are captains and jarls’. But captains and jarls have diversity within them too as we learn in the rest of this beautiful novel – and some of these diversities will reshape our notions of a communal paradise where the proximity of difference does not bring hate, violence and unnecessary death into play.

I now want to re-read GMB again. Honestly, who wouldn’t.

___________________________________________________

[1] Maggie Fergusson (2006: 79) George Mackay Brown: The Life London, John Murray.

[2] ibid: 161

[3] ibid: 280

[4] George Mackay Brown (1992: 122 – 124) Vinland London, John Murray.

[5] ibid: – 213

[6] The best example is beautifully written. See ibid: 119

[7] ibid: 24

[8] ibid: 168

[9] ibid: 87-89

[10] ibid: 230

[11] ibid: 168

One thought on “The queer confidence of a shy man: George Mackay Brown (GMB) and his late novel ‘Vinland’, where “boys love to range freely in the country of their imagination, and there they are captains and jarls”.”