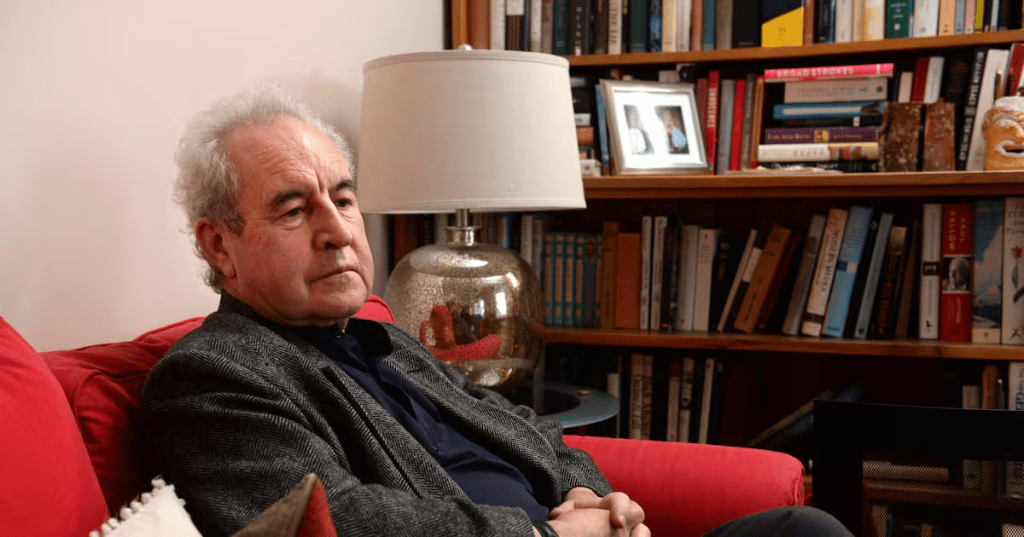

It seems odd to take as the text behind a blog not a great work reviewed but the review itself. Nevertheless today I do just this. John Banville is a great reviewer – the grim and rather schoolmasterly distaste for orthodoxy in which he specialises makes him a resistible public speaker but a novelist of fine sharply barbed sentences and an acerbic truth-teller as a reviewer. Once the darling of the academe himself for novels that spanned enormous revolutions in conceptual and moral European thinking,from Copernicus to Isaac Newton in his remarkable first series of novels, he was notorious for saying that the art of the novel lay entirely in the syntax of finely wrought sentences, that echoed ancient authority. The review I am considering entitled ‘Silent Catastrophes by WG Sebald review – academic writing at its most sterile‘ starts by playing that very game: ‘A time there was, and a recent time, when big beasts stalked the groves of academe’. Instancing this time are the beasts he refers to in the:

leafy days of Althusser and Paul de Man, of the terrible twins Guattari and Deleuze, of Foucault, Derrida and Sollers, of Susan Sontag and the delightful Julia Kristeva. It was the age of theory, after the demise of the new criticism and before even a shred of cannon smoke was yet visible above the battlefields of the coming culture wars.

Banville makes himself scarce in those time by indicating that he was, perhaps but perhaps not, one of the many forming the community that fed from the detritus of those beasts, whose true heir is the fanatical right represented by little men who sound big aping the words of the populace like Elon Musk and Donald Trump:

How sure of ourselves we were, the heirs of Adorno and Walter Benjamin. We knew, because Nietzsche had told us so, that there are no facts, only interpretations – sound familiar, from present times? – and that danger alone is the mother of morals. We listened, rapt, to the high priests of structuralism, post-structuralism, postmodernism, und so weiter. We pored in anxious excitement over the hermetic texts of the new savants, encountering sentences such as this, from the pen of a German-born academic who had been long settled in Britain, and who in the last decade of his life would mutate into a world-famous novelist: “The invariability of art is an indication that it is its own closed system, which, like that of power, projects the fear of its own entropy on to imagined affirmative or destructive endings.”

As much as Banville uses ‘we’ here, the more he emphasises that this community of followers of the ‘high priests of structuralism, post-structuralism, postmodernism, und so weiter‘, using German at the last to tie the problems raised by these intellectual movements to not only Nietzsche but Heidegger, despite the hegemony of Marxists in his first sentence of this paragraph. His attack dwindles however to one not on one of the giants but on the idea that even giants can write less than desirable sentences. What he ironically (nay, sarcastically) calls a mere example of ‘gnomic aperçu’ in Sebald’s posthumously translated and published academic essays is this sentence. After seeing it placed in the light of the incomprehensible by Banville, few will think it is not exactly that – not ‘gnomic’ or ‘hermetic’ both words that indicate that truth might be hidden inside and necessitate external syntactic and semantic complexity.

However, is that quoted sentence so complex? It makes a lot of assumptions and uses loosely defined words that presum a science behind them, like power and entropy, but its drift is clear – art and power evolve fictions with imaginary grandiosely positive or negative endings to defend themselves against knowledge that they too will pass away in time. In effect, this is the very target of Banville’s own prose – launched at ‘great beasts’ of the past that now seemed tamed to pet status.It happened so quickly too, Banville’s prose asserts: ‘There was a time, and it was a recent time,…’ is itself a formula that puts the passage away of myths in an instant in focus. Sebald’s workaday academic essays from obscure sources do not require republication. Published merely because the expectation of the modern academy is to publish regardless of whether you ave anything to say or not they largely ‘represent academic writing at its most convoluted, most resistant and most sterile, the deathless products of the publish-or-perish academic treadmill’. It is characteristic of Banville as a public authority in writing to still retain ironic descriptors like ‘deathless’ (where he means the opposite or worse – dead or decaying) when he has come out from under the play in his prose to nail down the coffin of a reputation with clear condemnations in his adjectives: ‘convoluted’, ‘resistant’ and ‘sterile’.

Later Banville will say almost ponderously as he hides the agency of his personal distaste under an impersonal passive voice: ‘It affords a reviewer no pleasure to be harsh on this book, …’. But the whole feel of the prose is the pleasure and play of the destructive element with its edgy ironies – too strong to be elegant and falling into sarcasm. It is after all nonsense to go on to say that the minor or workaday of writers of great like The Rings of Saturn have their reputation ‘diminished’ merely by showing that he could write with less energy and aryistic purposes at times in his life. Publication of minor works, experimental genres or conventional ones, do not diminish – they rather assert that great writing is not common even to the great writer themselves. There is no harm in seeing that writers are necessarily contradictory in their forms and style.

What Banville likes is those moments where Sebald rises to critique of the pretension of other writers, as in this paragraph, where ‘Max’ is patted on the back for his acerbity:

Equally but more darkly to be savoured is the demolition job carried out on Hermann Broch’s turgid monolith Bergroman (Mountain Novel). Sebald writes: “What we feel is not the intimations of transcendence that great moments in literature – and perhaps life – can give rise to, but merely a surfeit of sheer banality. In this sense, Broch’s ‘great novel’ turns out to be a complete debacle.” Now you’re talking, Max.

But is Sebald really writing like Banville as a reviewer here. In effect this sentence illustrates the one that Banville found convoluted, resistant, and sterile. Clearly Sebald is showing that ‘sheer banality’ can be the outcome of an expectation that you just have to write and keep writing to produce great art or even have and hold onto power over others. That is very less elegantly expressed in the earlier phrase that art and power project into their products ‘the fear of its own entropy on to imagined affirmative or destructive endings’, but it is an enlightening perspective on what makes us think bad literature and power really bad.

I am not sure I have time to add a hefty volumes, such as Banville describes this book, to my library of Sebald’s work but I think we do need to distinguish judgement of the value of the words of others from some standard of non-contradiction, sameness and lack of diversity, even in our energies and powers as a writer.

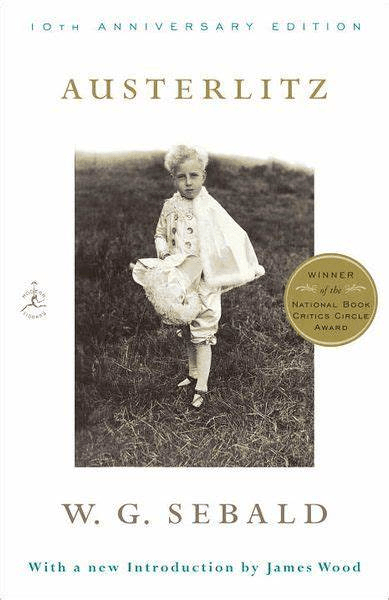

Banville himself is not harmed by much of the lesser journalism he produces or travel books. His best book Shroud remains the monument it is despite experimentation in detective fiction (some of it great in its way) or quick judgement-making in newspapers. Shroud however is not so great a book as Austerlitz, which Banvill also praises. But there room for diversity!

____________________________________________

{1} John Banville (2025) ‘Silent Catastrophes by WG Sebald review – academic writing at its most sterile’ in The Guardian (Fri 7 Feb 2025 07.30 GMT)