‘Everything moves. Everything passes. Threads tangle so easily, so completely. It is their nature to knot. …/…/ The truth is you must be everyone in a story to understand the story. …’.[1] A reader who comes to The Night Alphabet looking for a linear story and quickly understood connections between the novel’s sub-narratives (or some kind of hegemonic meaning that connects them to its characters) will leave unsatisfied. Others will just fall in the bodies that tread through this novel and struggle to get out from one to the other. Since when was reading just straightforward?

Leave all your usual ideas about reading behind, or at least store them at a distance from your reading of this novel, if you feel tempted by Joelle Taylor’s debut as a published novelist rather than as a poet. The stories in The Night Alphabet are unmistakably meta-stories, about how you read stories such as these (or other stories) framed in a meta-novel, a novel about how you read stories and their yearning (often provided as a collusion of main narrator and the reader) for connection to each other. In The Night Alphabet the yearning exists sometimes in the characters of two tattoo-artists in the novel – Cass and her apprentice Small – but even they leave much of the desire for connection in the novel while they carry on in a role they are paid to perform (to tattoo a ‘thread’ that links together the tattoos on the primary narrator’s body). That primary narrator is Jones. As each tattoo is stitched – the idea of a tattoo line as a threading together of holes in the body is important – Jones tells a story that explicates it and some of its symbols.

But in my view the practised novel reader can get the idea of a linked-up story as an explanation of a novelist’s themes wrong in this novel – for the links of story to the illustrative plates representing each tattoo that precedes it and to the whole framing narrative never work as completely seamless as readers are trained to expect by both the classic realist, modernist, or even post-modernist novel. Hence, although in an excellent review with many insights to which I am indebted, Wendy Erskine in The Guardian may tend to smooth out the experience of the novel, though perhaps in a longer consideration she would be more uncertain of the effect made by her magisterial sentences. Her first paragraph tells the binding narrative of the novel thus:

The already heavily tattooed Jones asks the two artists, Small and Cass, to connect all the images on her body by a thin line, using ink mixed with a vial of her mother’s blood. This will be an act of unification and completion.[2]

You cannot quibble with the reading of the symbolism here, but I can with the possible assumptions of the ritual meaning of those symbols in action: ‘This will be an act of unification and completion’. For though the act has this intention it is not clear that it performs anything like an act that helps as readers to unify what is fragmented in the novel, or complete what is in it that is incomplete. My own suspicion is that the novel leaves us with the necessary feeling, meaning and will to action based on the failure of any sustainable hope of that these elements will or ever can be unified, completed or indeed made into a pattern of which we are certain. Instead it revels in the fragments of stories, and a few threads that attempt to Taylor/ tailor it into a whole but remaining hanging gorgeously loose. Thus it is with the unities (or rather disunities) of time in the novel which are perfectly described by Erskine:

The 23rd-century tattoo parlour is a retro one. The tattooists may use holographic laptops to book a sky cab, but their workplace is designed to be mid-1990s, right down to its soundtrack, a hard house CD. Setting 1996 on an endless loop in 2233 is a deft introduction of coexisting time periods, a central idea of the novel and one responsible for a thread of dizzying and delightful inversions, reversals and paradoxes. At the start, we’re in the future, but Jones says she is “back”. …

Jones, like her mother and grandmother, has the ability to experience other people’s lives in an intensely vivid manner, “falling” into them across space and time; each of her tattoos denotes one of these “rememberings”.[3]

But again I would quibble with words here. That different time periods are put next to each other, and sometimes anachronistically combined, but that does not lead to a sense of ‘coexisting time periods’, but rather of ‘time periods’ whose edges are rough, uneven and contradict rather than coexist with each other. As a result one of the major themes of the novel – the analysis of sex/gender differences remains unresolved together with the equally unresolved role of images of the transgender within that analysis – and that is perhaps the point. The desire for complete and unified theories of life is the problem of post-modernity not its continuation of the modernist quest. There is joy in Joelle Taylor (that there is not in W.B. Yeats) that:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity.[4]

In The Night Alphabet people Yeats might have described as ‘the worst’, (a group of “prostitutes, drug users and poverty surfers” as Erskine aptly quotes the novel) become a heroic band of Gutter Girls. Moreover, resistant but already near-complete male constructs of femininity become martyrs for a revolution against the men and The Sons who rule their worlds for now. Yet both groups are full of ‘passionate identity. Mere anarchy seems better than collusion with a fragile virility when that is used as a principle of political-sexual and socio-political power. Wendy Erskine asks why Jones never, as she ‘falls into existences across space and time’, encounters ‘a bunch of benign or unobjectionable men’. But this seems to me art of the important incompletion of the novel. It asserts that there might be men of such sort as the latter but never finds enough of them to enter, so patterned are their lives by ideologies that sustain a power over women and resources that they dare not surrender. The moving but horrifying story of the INCEL (involuntary celibate) men (which Jones in the body of one of them calls as a group INCELLULOID) is a case in point. There is a disturbing making of excuses for, and a minute spoon of empathy for these rapists and murderes because the novel cannot resolves its contradictions – just as no-one in life can ever do such.

In this novel you are being continually reminded of learning to read or perhaps the need to revisit that learning to encompass the range of signs (or characters – glyphs I’d say for Ali Smith comes to mind here (see my blog on Gliff at this link) necessary for the understanding of a world that never can be more than anarchically contingent in its patterning of experience. Jones learned to read from a strange ‘baby book’, the tattoos on her mother: ‘They were how I learned to read’.[5] But whether and how one reads is a problem throughout the book, that opens first in its opening when Jones and her stories (yet in the form of tattoos) ‘materialise’ by ‘finding themselves again across my body’ and are called the ‘map of me’. However, reading a map is different from reading a book. And maybe Jones’s body is not a map for the folds and location of her body constantly shift and change, as she and others are looking for meaning and not finding it – what, for instance, is the status of the hanged woman below for instance if not a symbol, and if that, by what code would we interpret it ( for instance who do we think would consider it appropriate to be especially ‘curious’ about a ‘hanged woman’ on a ‘Sunday afternoon’). We are left with a puzzling conundrum:

Perhaps I look like a gallery rather than a tattooed woman. Perhaps I am a hanged woman, something to be curious about on Sunday afternoons. Maybe each of the tattoos is a still in the film reel of my existence, my skin a camera screen.[6]

How are we to read these two sentences? It becomes an issue precisely because the sentences concern different cultural artefacts that get read in different ways and with different preconceptions. Some of the artefacts, notably the multiple ways in which cinema films become accessible to be read as a mode of their consumption are used to show how we might consider the tattoos on a naked female body to be equally readable. The juxtaposition of stills and the function of a film projector to view multiple stills as if a representation of real-life motion do not help clarify the novel’s own use of still engraved reproductions on paper of the tattoos on moving skin nor does the film-projector at all create motion in the same way as the saccading eye that reads BOTH text and illustrations and neither is like Jone’s existence’ which, after all, is only a notional product of the effect of all the reading we do in the novel about her perception and being perceived as a body replete with characters and designs.

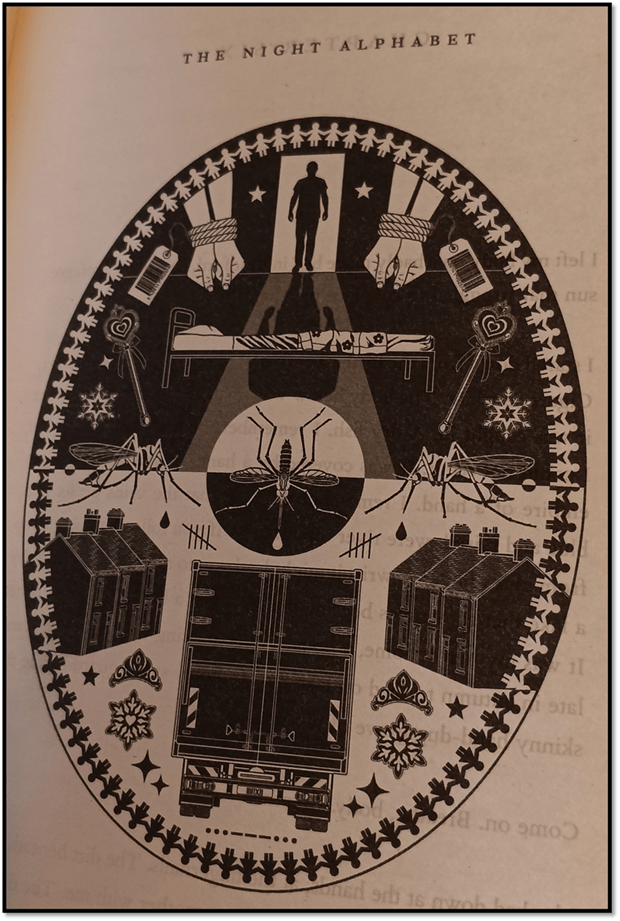

There is another instance of this that is even more puzzling in its textual riches, and deliberately so. Chapter Six is a chapter telling the story of a migrant body in the context of its migration in so many ways in which that could have meaning, even in the consideration of death as a migration, but that deals with migration not so much as a subject – although the story of an exploited female migrant underlies it – as a thing that flits from subject-matter to metaphor, even in its first sentence> Flits is a useful word here, for it not only evokes moving house but the motion of a mosquito, particularly one named Craig in the story that represents in necessarily masked form the identity of the people-trafficker involved. All of those symbols and metaphors live too in the ‘still’ representing the tattoo that is being read as the content of Chapter Six. (see below):a dark silhouette of a man whose inverted shadow is headed by a mosquito motif, a removal van used in the illegal transit of migrants and homes the van merely passes by, which no doubt are externally darkened by their secret contents. around it is a ‘comm’s surround is an embracing community of monochrome black and white papercut figures – in the dark side bound female hands. Of course as I parse it, I read it and interpret – rightly or wrongly for I have not the key to its codes – perhaps the keys represented in the picture. And having tried to read it I move on to the text, which tempts me to read it against the tattoo illustration for better or worse.

My photograph of the tattoo illustration prefacing Chapter 6, in Joelle Taylor op.cit: 89

But that’s no easy task. As an example try this imagined vision of Craig as the young girl migrants consider he may react were he subjected to the behaviours to which the police and immigration officials subject them. To understand how we read such counterfactual imaginings we have to think differently: ‘As they strip-search him, think of Craig as a girl. Think of him bending over and spreading. Think of the men who search him not really seeing him, only cavities and hidden places, only secrets and shames’.[7] Have you thought how immigration control ‘read’ a suspected migrant? Have you considered that their focused perception reduces the girl to cavities and imposes shame by their handling of them. Male culture, of course, has always done so metaphorically. Somewhere, but I haven’t re-found the page reference yet, Jones speaks of how Shakespeare spoke of women in terms of their genitalia which he called /nothing’: a round empty hole as a character and it is a usage that sings through this novel, as women are read as ‘nothing’ in a range of ways – of things better copied, disappeared or erased, except even the record of their disappearances are caused in themselves to disappear.[8] Sometimes women’s marks – their characters and words disappear so effectively the novel leaves us with a partial page – much of blank and, if labelled at all, labelled: ‘The white’.[9]

Now the novel knows that, in real social and economic terms, the vast majority of men count for nothing too. The Quiet Men are murderous in their effect but have been reduced to be a voice not their own and represented by an immature child – the ‘Grande Toddler King’, who seems to me a Gothicised satirical amalgam of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, both identifiable as the ‘politician of petulance and infant spite’. These me too are nothing but they find ways of manufacturing power from nothing so that they are, ‘ordinary man’ becomes ‘The Small Emperor of nothing’.[10]

Fearsome as these fakes are, Antichrists it is suggested from Revelation’s apocalyptic scenario, they hold power and that stops the sympathy the book forces us to feel – even for the worst of them – from being other than the unresolved background of the perfidy we see them prosecute – human slavery, rape, Instagram sex taping and even murder. But let’s return to Craig who we left above ‘bending over and spreading’ in our minds for his cavities to be searched. But he too can be read by power – so much so that his spine is a book-spine ‘of a cheap airport novel’.

I found the passage that reflects back on that search so amazingly full of the use of double meanings that compare it to reading – although the name of an ‘anal passage’ is a gift from the language of those searches, it certainly also describes a meta-critical reading of what some people might call EMPTY PROSE:

Passages, letters and spines are all the stuff of reading material as well as external and internal search, not unlike those invoke by close reading fans. The prose is not empty but will seem so if you are so inclined to see it and allows reading to seek new meaning, as in the deliberation evocation of different meanings to the term ‘daddy dealer’ that give not a bit of their context away. And this passage is important because it both reveals the emptiness of Craig, despite his bluster as another ‘Emperor of Nothing’ that has more in common with women than he is prepared to find, and if he finds it acknowledge or admit. That is precisely why the novel or Jones ever time’ encounter ‘a bunch of benign or unobjectionable men’. For these men require the empathy the prose often gives them, but do not want it since it would break the cover that has like that around the might Oz, nothing to support it.

Yet the novel insists that it must go into men empathetically, as well as bodily in the ‘anal passage’ above, to find what is there hidden – for it is not all bad and deformed (or sometimes not yet). Women inhabit male exteriors – an aspect of Taylor’s performance in real life too – in many ways. The most obvious – the attendees at a butch lesbian bar in Chapter 20 (‘Maryville’) who hang ‘tattoos from their body as if they were a gallery’, the ‘best bois (sic.)’ who all were ‘cut from the same fabric roll. Different suits.’[11] However, these are definitely conventionally suits that look like those once wore by men, with their hands round a pint glass – one of the codes in the prefatory tattoo illustration. In the illustration not all of the codes are used in the story like the crossed Amazon axes, the inverted triangle (for queerness) overlaid by Amazon fist ear-rings. The knives and belt keys are mixed by images of flowers that feminise this particular male such that it is the binary distinction for sex/gender is appropriately queered. It is actual male violence that reverses the genderqueer symbolisation and is meant to, as if men needed to maintain the power distinction through violence facilitated by more developed muscle: ‘I was beer and fury, pushing the boys back from behind us. … We had forgotten our breath. I had the clothes but not the body, not the energy required to absorb and return punches with full-grown men’.[12]

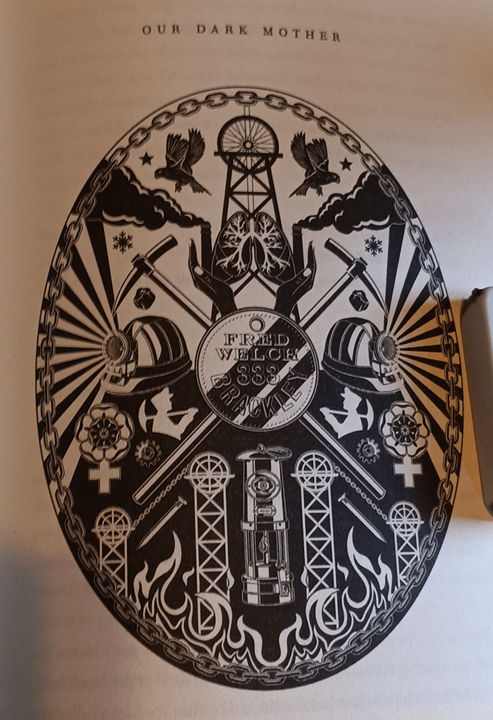

This violence as a reflex of physical nature though hardly applies to the INCEL young men who use only the reputation in men for violence as part of their scheming, but the end is the same – power and collusion with a male mythology of some toxicity. The other example of cross-dressing relates to the story of Winifred (soon to become Fred) Welch who in the early twentieth-century tries to address her family’s poverty after the death of her father by dressing as a boy to go into the mines. But Winifred had already seen the issue of sex/gender as highly complex. For men thought of the pit as a ‘dark mother’, a whole into which you descend in threat of your life and who is a most ambivalent woman – miners traditionally call coal mines ‘she’. When her father was alive moreover, she remembers the time she ‘saw the woman inside my father’. It is a beautiful passage. Read it for I won’t quote it.[13] Hence when she descends the pit with her budding breasts bound to avoid detection, she realises that the dark of the ‘dark mother’ envelopes all sex/gender distinctions frightened only when men become dominant and fill up that dark space: ‘Th men are afraid of t’dark. The dark is afraid it is filled with men. It is its own world, the under night’.[14] The phallicism of the mining tattoo is bound by a chain as Marx says that the working class but that phallicism focuses around the name of Fred Welch (really Winifred Welch), the White Yorkshire roses are coded signs for women not men.

But there are other ways that women can get inside men: not least by the empathy required to make their minds AND bodies lives as characters in a novel or in a story told outside of novels. The young foreman even feels that his responsibilities will make him cross sex/gender and familial boundaries wherein : ‘We are all inside each other’, as we are all – girls too he knows as Fred Welch dies a boy he knows to be a girl.[15] Jones contradicts Small’s more simplistic feminism than her own. Her stories may seem to be all about women but they are not. Jones tries to explain to Small, using her usual metaphor for empathetic entry – falling into the bodies of others.:

I suppose that being female, I am more drawn to the female experience, but it’s not exclusive. I’ve fallen into the bodies of boys and spent tears trying to find my way out. / … / … Once in the body O forgot all other bodies, all other experiences. …[16]

Small cannot grasp this. She still feels that she lacks the answer for what it feels like to fall into the body of a male rapist and murderer as in the INCELLULOID story, the incels being ‘castrated gods’ angry at the independence of women they have aided and facilitated into the world with women.[17].And she is no more wrong to be puzzled about the handling of sex/gender distinction in this novel than Wendy Erskine. It is a novel bound to the feminism that feeds it stories of male perfidy in power structures and female attempts at communal strength, but it holds out hope for a more non-binary world I think. I hope. That the men in the novel not only exploit, murder and rape women because they fear their role as bearers of children – in the final story, they try and circumvent all that – and though unable to bear children themselves, externalise women’s wombs and reproductive organs in a factory to avoid the problem altogether.

Meanwhile women try to work with negative male representations of them as castratos, bearing a vagina thought of as a ‘wound’, a tunnel (like those in Brackley Park pit (or anti-matter ‘black holes’ in the cosmos), to nothing. The butch lesbian bar, Maryville is seen almost as a product of this imagery: where the wounds that are acquired through oppression and homophobia are equated with the wound they are seen as women lacking a penis in sexist ideology (that reproduced in the early Freudian concept of penis envy – he abandoned it later, perhaps in response to his own daughter, Anna’s, open life as a lesbian):

Women get ‘inside’ men in a few of the cases in the book, but it is also concerned with the intrusion of men into women’s lives and the appropriation of their interiors, Like the ‘(m)any men that lived in’ a prostitute known as a Bold woman, ‘paying her with pennies’.[18] That is the whole point of the final story of the womb harvest factories in which women were allowed to ‘become human’ by freeing them from ‘biological determinism’. Parts of this story read as if the product of a satire from that narrow movement that calls itself radical feminism. Its men are mocked for enforcing the lesson that: ‘Biology is really socially constructed’, [19] I have my own issues with this chapter but in the end, it is merely another way of reading women’s lives that at some level is a necessary part of the sex/gender story, especially of the meaning of modern heterosexual marriage. The main way men get inside women in the novel is by violence.

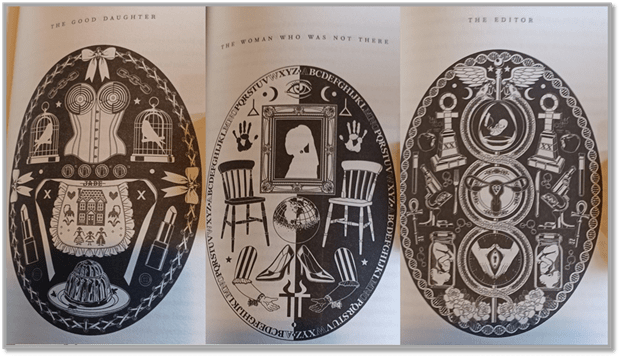

The most important use of the idea of the interpenetration of bodies in the novel is that symbolised in the tattoo needle – that maker of holes that pass for lines and through which, because they are link to oral stories, women enter into each other’s lives. The dark allegory (to borrow a phrase from Spenser) is that in which the visit to the tattoo parlour is read as a return to a family home, where the boundary between Small and Cass – and Jones mother and grandmother cease to exist because all families begin to mingle – chosen as well as biological ones. This is not though my main interest in the novel, together with its link to mystical imagery of female bonding across myth, history, and imagination. These play out in the tattoo illustrations by the artist Emily Witham, presumably working in close collaboration with Taylor. Here is a collage of ones I have not yet used:

Coded representations of women abound together with the binding motif in the novel – the lemniscate (the infinity symbol). They range through many stereotypes and simplifications but can only be read as pat of a design that complicates them. But those acts of close reading are for the reader to do, having decided how it is done. My point is that they cannot be read simply but only in their complex integrity where they ironize and comment upon each other in order to make us feel and think differently. I certainly fee that they had that effect on me.

They speak to me of the way in which the novel argues that women exist only inside each other and in the transit between being exterior object and inner subject of each other. And that this involves blurring of boundaries sometimes with men is also important for men and women can be inside each other, if only as a potential for which the world bears too little evidence. The ‘dark mother’ is an important symbol and perhaps in its diversity and inner fractures of meaning, the only integral one. As Brackley Wood pit, she is a hole into which people look down and into which some fall never to rise. But in that she matches other metaphors f the mother as hole, wound – to an internal world beneath the skin also revealed in tattoo making – womb or vagina, and grave (another cusp into new life through stories). These ideas emerge early. Jones knows that other people fear her fragmentation. Given the phial of her mother’s blood, Jones allows it to fall with a ‘solemn beat’ into the conversation because she knows that: ‘I need to feel connected to her’. People demand integrity of meaning, feeling and action from us but Jones knows that in part her symbols are only an appearance, a feeling of connection. For women this ‘feeling’ is associated with a mother – dark because difficult to comprehend like all dark things: ‘I look down as if into my mother’s grave’. This moment of looking down (sometimes looking up) into a hole is the issue. Yet Jones knows that it may be an illusion: ‘We listen intently to the nothing’. And there’s that word again – Shakespeare’s word for the female genitalia.[20]

Girl children working in coal mining in modern day India. Available at: https://www.mapsofindia.com/my-india/government/need-for-action-against-employment-of-children-in-mines

Winfred, the 13 year old, sees falling into mines as falling ‘into a different body’, a girl’s body thought to be a boy’s. In the same way Jones falls into stories that connect her to an infinity of persons and symbols of infinity – people holding lemniscates. Small wonders what she is ‘falling into’, but Jones cannot answer.[21] Yet as she tells and Small and Cas listen to stories they all fall into stories: ‘The story we fell into was one I would have needed help to climb out of again’.[22] It is the story of the ‘Gutter Girls’, and everyone knows how hard it is for women to climb out of the gutter men place them in except collectively. There are many examples in which falling matters as a transition to another identity. The whole tattoo studio framework Jones describes as : three women endlessly falling from our bodies and landing in strangers’ skins. … We wanted to share the same stories. We wanted to fall together and to remember the falling’.[23] And that means, let’s face it, Small and Cass as the morph to and from into being Gran and Mum for Jones, sometimes with Jones knowing the experience of having ‘fallen into the bodies of boys’.[24] And, as I have quoted earlier they also fall into the absence or hole that is a wound, or vagina or black hole invented for them to be their whole self, though it is only a part of something as valid as anything possessed by males.[25]

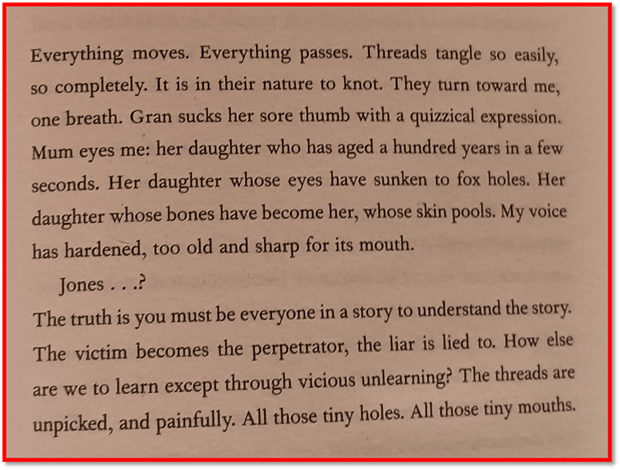

I need to end with the passage I cited in my title which precedes a key passage about falling into diverse spaces as a means of finding that identity is by its necessary nature diverse not integral. Jones says that she must ‘balance on the edge of holes looking down, knowing one day I might be looking up. How easy it is to fall into yourself. How hard it is to climb out’. Unified identities are not only holes we fall into but things that confine us within them. Hence my title passage. See how fragmented it is by seeing it whole.[26]

I will end with Wendy Erskine’s conclusion about the novel. It is also my conclusion:

More than anything, this is a novel about the power and importance of stories. How Cass and Small connect to them is significant, but equally important is how we as readers respond. … Like water, Jones says, stories can get in anywhere. They’re rich and fattening. A story is an infinity: inside every story is another.

That being so let’s not fall though into the hole of thinking infinity as equivalent to the integrity the novel aims at. To be frank it may aim thus, but that only matters if we are clear that finite ,minds can only know ‘infinity’ at the very most as disjointed fragments od a whole that may or may not exist except as an idea that is never embodied in such but only in perception of bits of bit in transit into each other. Infinity is symbolised the ‘number 8 on its side’. Turn it the right way and the infinite becomes a finite ‘8’ again. Moreover as such it resembles an ‘egg-timer’ and time ought not to be a feature of the infinite. That is where Jones, relieved at Small’s exasperation with her explanations, says that ‘the way to create infinity is to tell a story’, more or else providing Erskine with the conclusion she came to above.[27]

Do read this wonderful novel. Read it not as if you know how to read it but in the humility of being shown that reading is mysterious – even its objects are mysterious regardless of the subjective process. In that open way you will love it. Go to it with a boxed-in mind and you will hate it, and it may hate you in return. Not me though – all my love to you

Love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Joelle Taylor (2024: 413) The Night Alphabet London: riverrun

[2] Wendy Erskine (2024) ‘The Night Alphabet by Joelle Taylor review – relentlessly inventive’ in The Guardian [Thu 22 Feb 2024 07.30 GMT} Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/feb/22/the-night-alphabet-by-joelle-taylor-review-relentlessly-inventive

[3] Ibid.

[4] W.B. Yeats The Second Coming. Available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43290/the-second-coming

[5] Joelle Taylor op.cit: 18

[6] Ibid: 1

[7] Ibid: 121f.

[8] Ibid: 309ff.

[9] Ibid: 115

[10] Ibid: 242

[11] Ibid: 330 & 333 respectively.

[12] Ibid: 347

[13] Ibid: 19

[14] Ibid: 65

[15] Ibid: 77

[16] Ibid: 303

[17] Ibid: 134

[18] Ibid: 131

[19] Ibid: 356f.

[20] Ibid: 9 – 10

[21] Ibid: 46

[22] Ibid: 187

[23] Ibid: 227

[24] Ibid: 303 (as cited above)

[25] Ibid: 337

[26] Ibid: 413

[27] Ibid: 45f.