Now here’s a blog prompt that I never ever thought I would answer. My usual recourse to etymology to find a nuance in the question has already reached a block. In the UK we use the term ‘candy’, only because we see and hear the word in USA cultural imports, The UK word for candy is ‘sweets’, I suppose, regardless of the fact that this is a term for a pudding or a dessert here too. That children in the UK eat ‘sweets’ though rather than ‘candy’ I now assert with trepidation. It, at least, WAS THE CASE for the generations of children in my memory, but now … who knows.

Well, etymonline.com thinks it knows. Here is the entry for the word that, though it offered no interesting nuance for a blog, did tell me facts about the derivation from the word that surprised me, since the word is traced back to Sanskrit – usually a sign of an ancientness that we regard with awe. And how difficult to treat ‘sweets’ with awe; though I suppose children sometimes feel exactly that at the ‘candy stores’ illustrated in the college above.

candy (n.) : late 13c., “crystallized sugar,” from Old French çucre candi “sugar candy,” ultimately from Arabic qandi, from Persian qand “cane sugar,” probably from Sanskrit khanda “piece (of sugar),” perhaps from Dravidian (compare Tamil kantu “candy,” kattu “to harden, condense”). / The sense gradually broadened (especially in U.S.) to mean by late 19c. “any confection having sugar as its basis.” In Britain these are sweets, and candy tends to be restricted to sweets made only from boiled sugar and striped in bright colors.

But the very notion of ‘candy’ has always seemed to me to be overwhelming in its insistence on the sweet – a sweetness that is too much, and perhaps in the end cloying with the eventual deaths it helps enable. How much of that feeling is personal and how much picked up from associations in culture I do not know. Certainly the Brothers Grimm, those barometers for the detection of deep-seated horror under sweetened surfaces, worked hard to educate children into a consciousness of the horrors of the adult world using the motif of the delight of children in sweets. In the story of Hansel and Gretel, the two eponymous children find that their stepmother has decided that, especially in times of economic depression and hunger, are too costly to feed and works out a plan, with her more reluctant husband, to ensure they are lost in the forest and will starve or otherwise be lost to their parents as the parents desire to be the case. The parents fail in this endeavour more than once until the stepmother takes them in a last attempt far deeper into the forest. Following a bird, however, they come across a house ‘ built of bread and covered with cakes, but that the windows were of clear sugar’. Hansel does not hold back, for he knows the calorie value behind sweetness.

‘We will set to work on that,’ said Hansel, ‘and have a good meal. I will eat a bit of the roof, and you Gretel, can eat some of the window, it will taste sweet.’

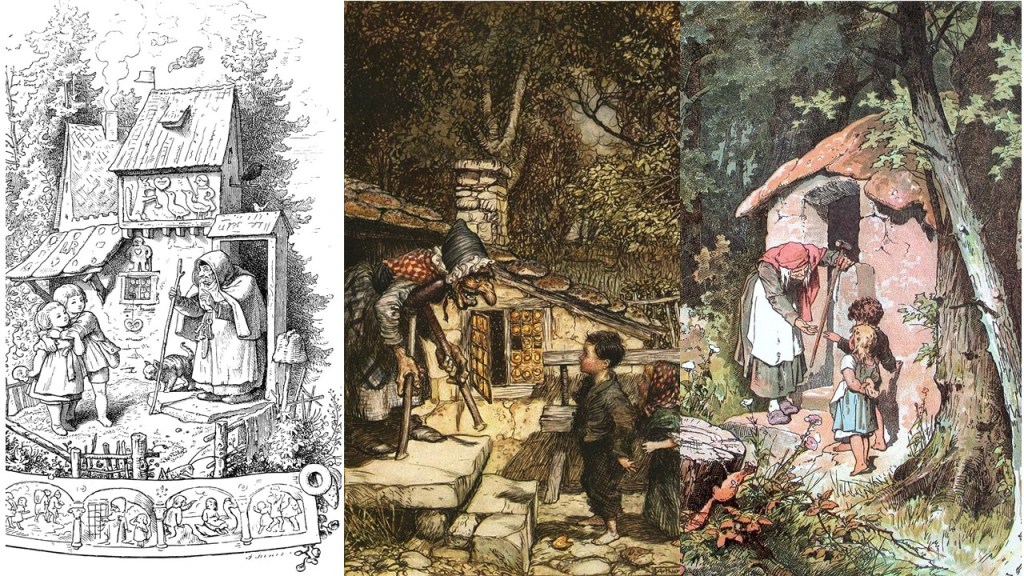

Even from the earliest times (see Ludwig Richter’s 1842 version on the left of the collage below) illustrators of the story have turned this house into the appearance of the modern candy store. Arthur Rackham (centre in the collage) rather gives the game away about the horrors of a candy house, in the monstrous visage of the witch that built it, welcoming in Hansel; the bolder of the two children, though Alexander Frick (right) makes the witch more inviting like Richter (and the sugary candy house more sweet). Richter however surrounds the house with fables and visual parables of falling for the lure of pretend sweetness.

The text of the Grimm Brothers however makes the witch’s horrific predatory nature act anyway only as a shadow allegory of the action of the children’s real parents, a means of undercutting the talk of sweetness and joy with which ideologically children are discoursed about whilst being prepared to become wage slaves for the status quo. The children use their sweet innocence to eat the witch out of house and home, without a clue that this merely reproduces their relationship to their parents which has already led them to attempted abandonment and exposure to the unkind elements:

Nibble, nibble, gnaw, Who is nibbling at my little house?'

The children answered: 'The wind, the wind, The heaven-born wind,'and went on eating without disturbing themselves. Hansel, who liked the taste of the roof, tore down a great piece of it, and Gretel pushed out the whole of one round window-pane, sat down, and enjoyed herself with it. Suddenly the door opened, and a woman as old as the hills, who supported herself on crutches, came creeping out. Hansel and Gretel were so terribly frightened that they let fall what they had in their hands. The old woman, however, nodded her head, and said: ‘Oh, you dear children, who has brought you here? do come in, and stay with me. No harm shall happen to you.’ She took them both by the hand, and led them into her little house. Then good food was set before them, milk and pancakes, with sugar, apples, and nuts. Afterwards two pretty little beds were covered with clean white linen, and Hansel and Gretel lay down in them, and thought they were in heaven.

The old woman had only pretended to be so kind; she was in reality a wicked witch, who lay in wait for children, and had only built the little house of bread in order to entice them there. When a child fell into her power, she killed it, cooked and ate it, and that was a feast day with her. Witches have red eyes, and cannot see far, but they have a keen scent like the beasts, and are aware when human beings draw near. When Hansel and Gretel came into her neighbourhood, she laughed with malice, and said mockingly: ‘I have them, they shall not escape me again!’ Early in the morning before the children were awake, she was already up, and when she saw both of them sleeping and looking so pretty, with their plump and rosy cheeks she muttered to herself: ‘That will be a dainty mouthful!’

The Grimm Brothers, however, were not really moral storytellers showing children the danger of taking sweets from strangers; they in truth rather uncovered the adult realities underlying childhood fantasies. The children are not punished for their fascination with the sweetness of candy but merely have to learn the hard lesson of the nature of adult exploitation. We could spend a lot of time on this story but I will let it suffice that I point hungry readers to the re-telling of the story in verse by Simon Armitage who sees in the event of the children consuming hungrily the witch’s house:

The psycho-candy doing its work,

...

But you know what they say?

No such thing as a free lunch. No gravy train.

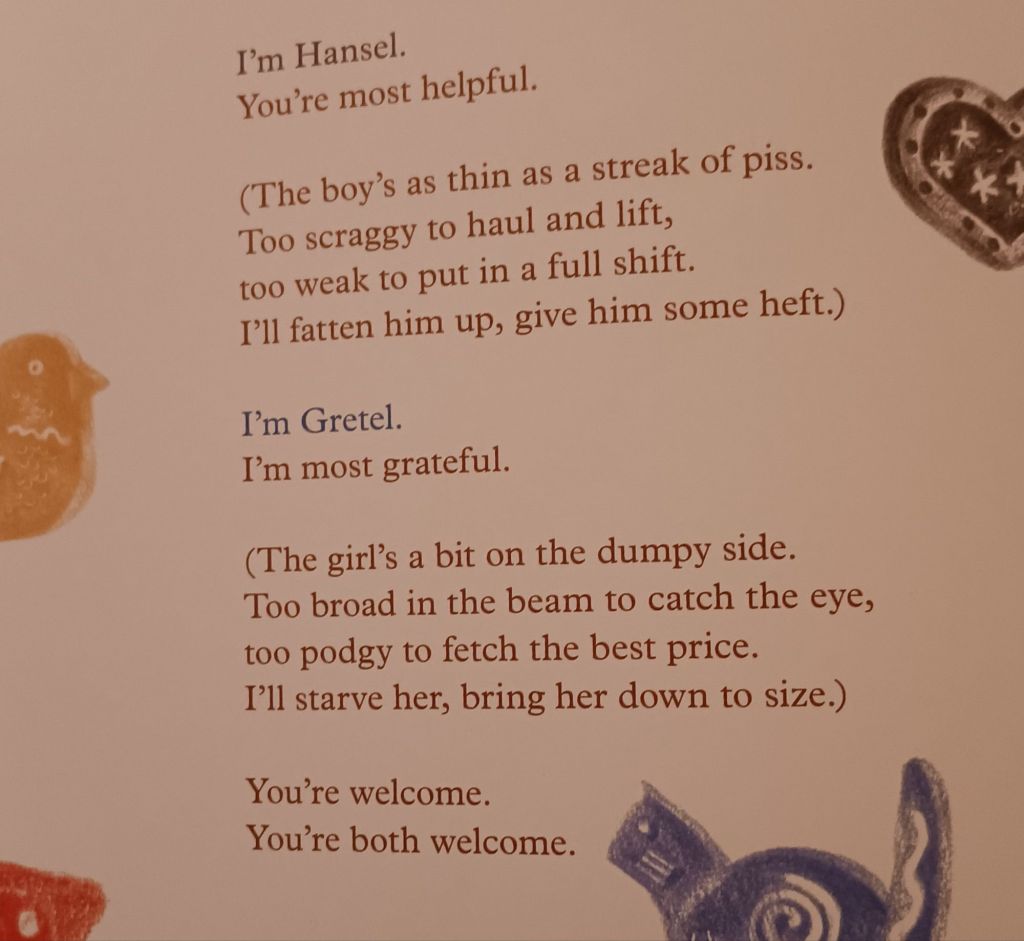

Armitage’s witch is a greater monster than that of the Grimm Brothers but at least she only ‘eats;’ the children by planning to turn them to work, and being a protector of the sexist binary, Hansel will be muscled up as as a worker of physical labour, Gretel to sex labour. Here are the witch’s thoughts:

Simon Armitage [2019] ‘Hansel & Gretel: a nightmare in eight scenes’ London, Design for Today.

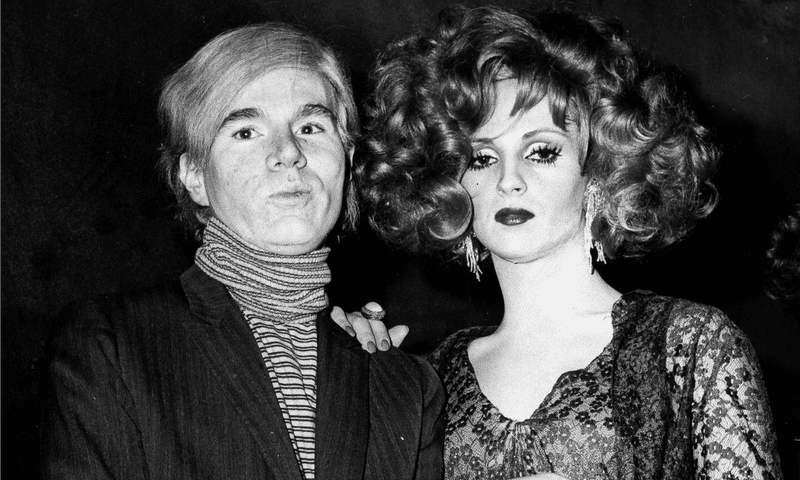

In truth there are other versions of the ways in which the childhood liking for candy are used to illustrate behaviours in adult life. I have blogged in the past on Lou Reed and the work I favour by him – in the albums Transformer and Berlin (for my blog on Reed see this link). I mentioned Candy Darling there. Candy appeared as one of the stories of queer men and non-binary persons in the song Walk On The Wild Side from Transformer. Amongst the cast including heroes who transformed their own miserable start in life into triumph over convention were Holly, Sugar Plum Fairy , ‘Little Joe never once gave it away / Everybody had to pay and pay’,and Jackie: ‘just speeding away / Thought she was James Dean for a day’. But most haunting is Candy Darling. The name is apposite, Her Wikipedia entry says that ‘she took the name “Candy” out of a love for sweets’, and adopted the surname because a friend of hers called her “darling” so often that it stuck’. The mythicised version turns her ‘friend’ into the men who frequented the ‘back room’ where she would give ‘head’:

Candy came from out on the Island

In the back room she was everybody's darling

But she never lost her head

Even when she was giving head

She says, "Hey, babe

Take a walk on the wild side"

Said, "Hey, babe

Take a walk on the wild side"

. . ."

The ‘wild side’ is the place the Witch takes Hansel and Gretel – a place of continuing exploitation in which one’s sweetness and vulnerability is turned into the stuff of the sordid fantasies of others. But the fantasies of those doing the walking are not sordid, except in as much they are forced behaviours taken on in order to survive and have in them a heroism which caused many queer artists to turn them into art – like Leigh Bowery, an exhibition of whose work opens at Tate Modern in London at the end of February – I am going (see my blog saying so). Candy Darling transforms her apocryphal love of sweets metamorphosing into herself enacting a candy shop of sweets into a lesson about art and life:

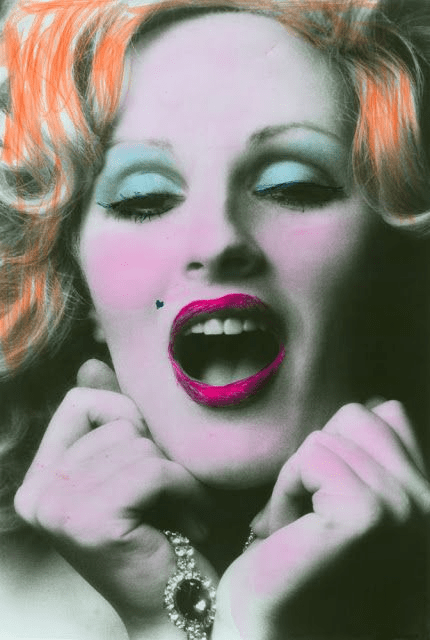

Glance at the layers of reference in the artful photograph of self-making above. It emphasises the fact that, for our society, most ideas of attraction and the attractive are a taste turned to the over-sweet – the confected; often using artifice and colour that mimics in an outrageous over-the-top way rather than represents the object that it attempts to signify. Above Candy’s blusher is a pastiche of the meanings of the blush in sexual ideology, which is read in women as sexual consciousness that is being made available for all who go on to take it, even take it violently. Candy was the master/mistress of the over-signifying sign: her whole existence told of the surfaces that attraction had been colonised by – the look of film stars, the kind of naturalness of body that can be only applied in face paint and powder, and sometimes with the help of photo-trickery. Neither ‘sweet’ nor a ‘darling’, Candy showed the falsity of those masks imposed on the desired by the agency doing the desiring.

Masks, even death masks (looking like facial-mud pack masks) were her specialty – what she turned to the gaze for them to be noticed and differentiated from their ideologically buried meanings of beauty and possession (like the fake diamond jewel fondled in the photograph I showed you first).

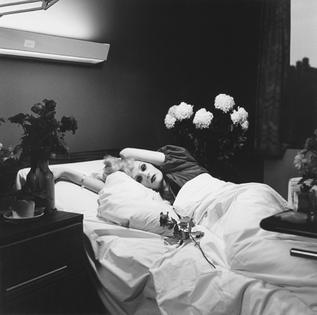

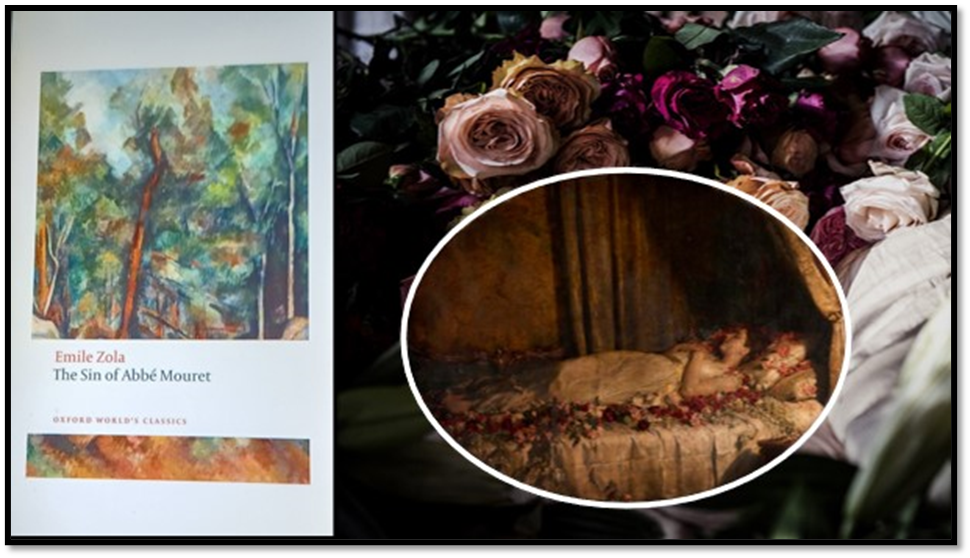

The death-bed pose above reminds me of that in Zola’s The Sin of Abbé Mouret that so fascinated Van Gogh (see my blog on this at the link here) and adverted to in the collage below I made for that blog.

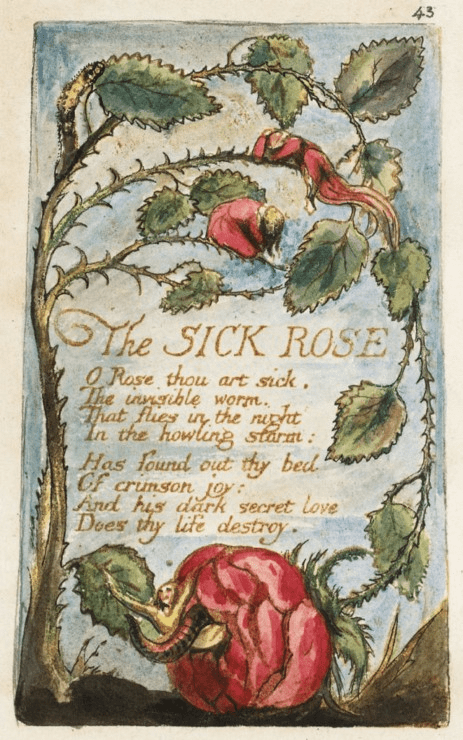

That Candy Darling’s sweetness often looks as if it is turning sour is no contradiction to all this. She was no Judith Butler but the lesson is the same: ‘performance’ is a wheel, like Ixion’s or St. Catherine’s, that the human animal is bound to. Its variations are a mirror of the doubleness that wants to believe in innocence only in order to have the experience of despoiling it. We need no myth of the Fall, or even Blake’s The Sick Rose, to be convinced of this.

Candy Darling was the imago of the candy of whose ‘secret bed’ adult men invade and destroy, knowing that there are more fish in the sea. Candy smiles as she hears this. For one moment, her painted mouth looks large enough to open up and devour that which made her its icon and its enemy, subversively in the latter role undermining its power to attract.

So my ‘favourite candy’ is that idea of candy – for the eye, tongue or tummy – that knows it will be regurgitated and live to re-envenom the venomous till they can exist to destroy honesty no more. I sort of like that more in Candy than in Andy: there a couplet again

"I put my face on with more care than he:

That guy pouts but that's not, you know, for me

Ask me: Go on, ask me but never ask

That I will be more to you than a mask".

Think there's better growth in mind with Andy!

Perhaps sick minds that secrete their own candy

I prefer the double mind in Candy

Than the smug singular of sad Andy

With all my love as ever (back to books tomorrow – Joelle Taylor in fact)

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxx