‘Stop saying words, my sister whispered back. I want to hear the story’.[1] The paradox may be that we express our identity in words and names not in the process of telling and hearing our stories. I think Ali Smith thinks that may be true of the configuration of sex/gender too. This is a blog on Ali Smith (2024) Gliff Hamish Hamilton.

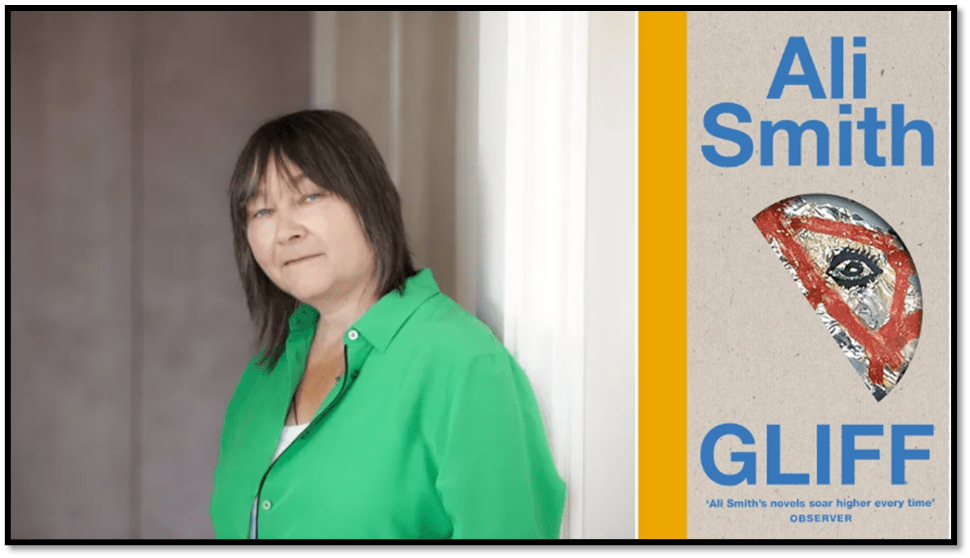

Ali Smith (2024) ‘Gliff’ Hamish Hamilton.

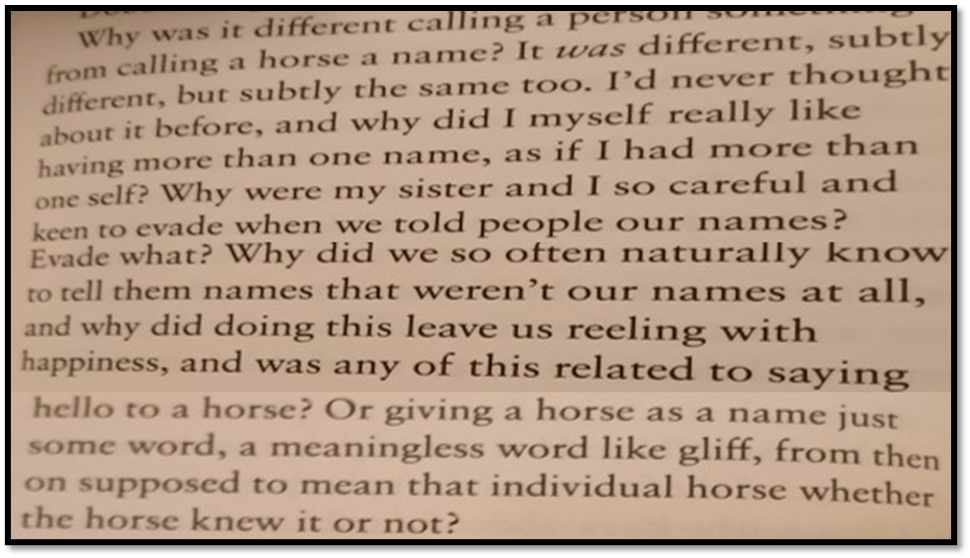

There is an artful indeterminacy in true story-telling, as the book Artful by Ali Smith told us a long time ago; there is something ‘accidental’ too about appearance in stories as in her first novel to raise this novelist’s public profile, The accidental. This book is the first volume of two novels: this one called Gliff, the other by the overlapping homophone of a title Glyph. Both stories obviously will discourse about the notion of words, especially when words become words and titles, whilst remaining what they are, mere glyphs or marks on a page that someone reads as writing with meaning or as written characters with significant voiced sound (hence the important in her work of homophones) , and understood meanings (often multiple meanings) attached. That is why the term Gliff matters as the sign of what integrates the repertoire of stories entitled by that term: it is a word but it a polysemous one – each seam of its many meanings (which sometimes contradict each other) having purpose in the nov whilst also being a name (of a horse). The name given to the horse called Gliff is almost accidentally given since the giver, Rose (Brice, Bri or Briar’s sister) claims she was not in control of its meanings at the time. There is a riff on how we get and who gives us names – which are but ‘words’ after all – on this subject.

The theme of naming is borne out in the naming of characters – Colon who is renamed Colin for instance and then returns as Colon – and in the manner in which the narrator (Bri … etcetera) gets their names variously intermixed. The effect of this on Bri is to make the achievement of a verifiable and securely enforceable identity for them (including sex/gendered identity) difficult – since they are thrust into a world that requires the elimination of non-binary identity. Bri, Brice and Briar becomes Allen Dale, a name (unbeknownst to his interrogation team in the novel) of a town in a tale told in a folksong.[2] Nevertheless the sex/gender complexity of Bri disappears under the new name for a boy, who will become a man and collude with a tyrannous governmental force in society.

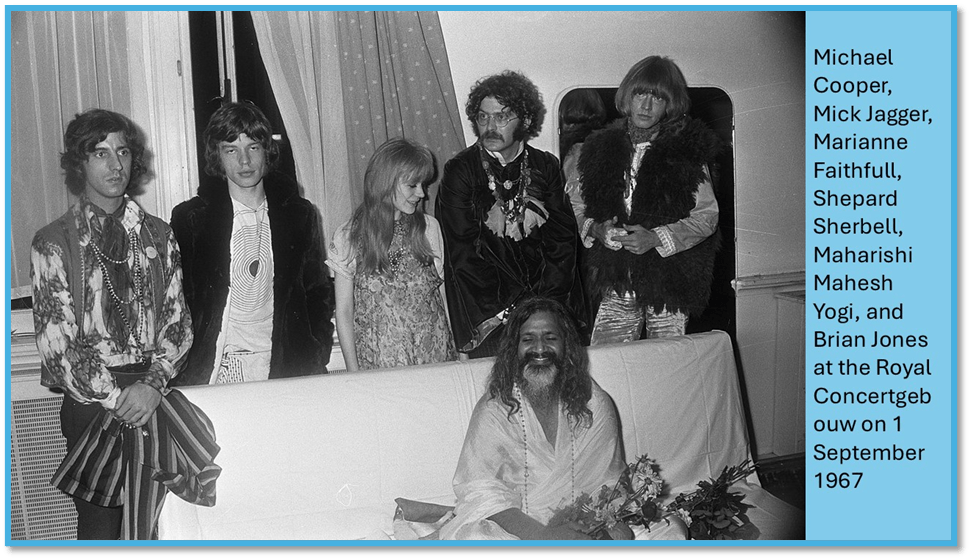

Names can be adopted too by people in this nov as part of their play with their known (or otherwise) multiple identities. Do we need to know who Marianne Faithfull was, for instance, to understand why Rose chooses (or has chosen for her by the author) the name Marianne Faithless. It all gets played out in further games and puzzles wherein the reader may be in the know or not of possible further and more variably sourced, association of tje nme’s origin:

The idea of whether Marianne was a Faithful or Faithless person was very much a topic of the medi at the time who constructed her image during her youth both in terms of her relationship to Mick Jagger [who was not even expected to be faithful to her or anyone else] and to the religious fashions she and contemporaries indulged, including the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

I’m Marianne Faithless, my sister said.

Not Rose, then, Oona said.

Did you tell her? My sister said to me.

Just your name, I said. Her name ‘s Oona. She’s the one and only and her grandmother was a goddess.

Was? My sister said. Can someone stop being a goddess? Like, get out of being one?

Someone called Marianne Faithless probably could, Oona said.

She likes to name herself, sort of, after the singers from the past that our mother likes to play us., I said

Thank you Briar, Oona said.

Liked to play us, my sister said. Long ago when we all lived together in a whole other story.

Why does she keep saying your name wrong? Colin said.

Sometimes I get called one of those names, sometimes the other, I said.[3]

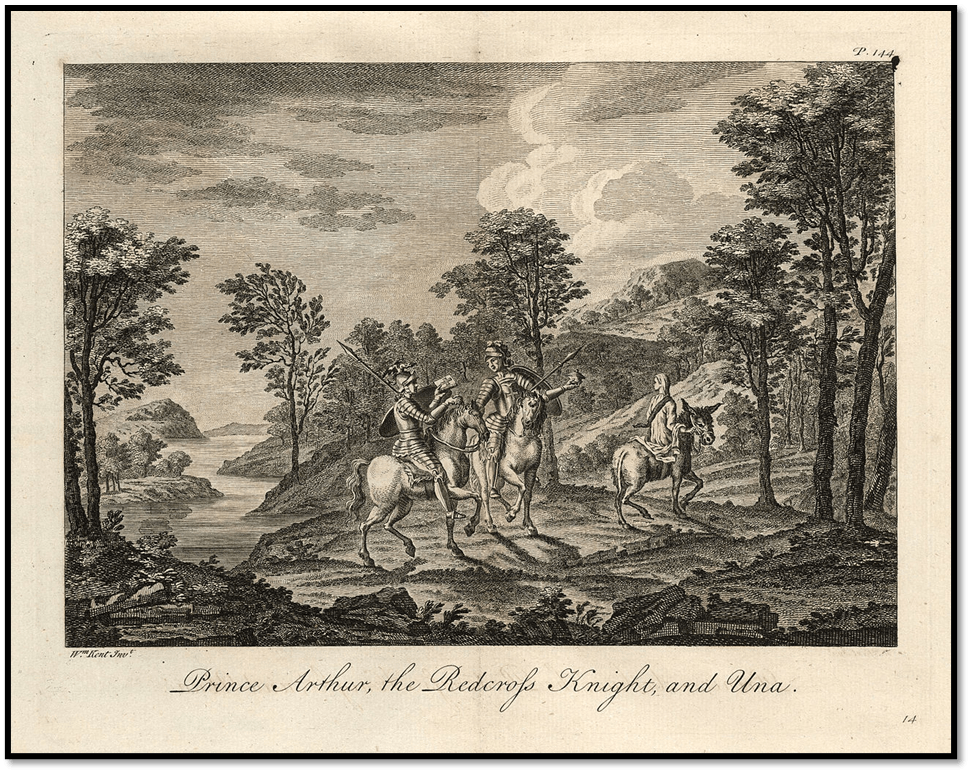

Ali Smith’s work always contains, though it uses them with the lightest of touches, a tissue of layers of cultural reference of the widest range. We are told that the Marianne Faithfull resonance had much to do with that ‘other story’ of the childhood of Bri and Rose and the stories told them by their mother, and the songs she played them from ‘singers from the past’. Even when the text I quote above refers to Oona, it refers via one of those past songs: Chesney Hawkes ‘I am the one and only’, itself a song under the title Buddy’s Song, about the nature of fictional intrusions into reality. But the reference to the ‘one and only’ fixes another meaning of the name Oona. It is one referred to in the Latin version of her name, Una (and is that used by Edmund Spenser to name the female hero and Faerie Queene in his long epic poem. Una in Spenser’s The Faerie Queene is elsewhere in that poem the goddess Astraea, the queen Gloriana – and hence Elizabeth I – and the one and only holy church led astray by Rome, which the English Church under Elizabeth aspired to be. You see Una thus in William Kent’s 1751 illustration below, riding on a donkey, bearing the weight of the Christian message in her body, actions, and association.

Spenser was of course Elizabeth I’s envoy in Tudor subjugated Ireland and the series of Celtic names of the fairy queen, Oonagh too in Western Ireland (and strangely enough Finland too) was his source: Oonagh, Oona, and Úna and thought to be ‘lamb’ in Celtic and hence easily adopted as a Christian myth, with a reference too to the concept of a gentle being in both nature and Irish polytheistic supernature. In the Celtic version of Oonagh, Úna, the name almost aspires to the Latin meanings of the name but for the acute accent on the ‘U’. Although a fairy queen herself in Irish folklore, Oonagh was descended from goddesses (and gods – The Tuatha Dé Danann). As Bri says, Oona descent ‘was’ (to Rose’s chagrin) from a grandmother who was once a goddess. Rose insists. If this grandmother was once a goddess says Rose, taking the word ‘was’ literally, wasn’t she always one such. Rose’s take on language and the meaning of words and names of people, things, and actions that are done by people is surprisingly literal compared to Bri, except when she herself masks herself under another name like Marianme Faithless..

The Tuatha Dé Danannas depicted in John Duncan‘s Riders of the Sidhe (1911)

The tissue of references I you to see as sometimes fleeting presences in the passage above are never there to highlight the learning of the author, sometimes the case in A. S. Byatt for instance, whether intended or not, but to show that the cultures we live in are a sea of submerged of references that occasionally float to the sea’s surface. The fairy tale associations of The Rose and the Briar play there too and add to the theme of names. As we read on and through all of these examples we realise the fallacy in Rose’s position on storytelling cited in my title, a position that would eliminate every novel ever written by Ali Smith, at least after the shattering The accidental. There is no way in which Roses binary characterisation of language usage can really be the common sense it sounds like, as Rose often sounds like but is not: ‘Stop saying words, my sister whispered back. I want to hear the story’.[4] Because truly considered the story is words and words are the story. Without knowing that we will never truly ‘hear the story’. Nowhere is that clearer than in the treatment of sex/gender in this tremendous book.

But, of course, to understand that last statement, we need to keep on following the treatment of naming, interactively communicating things about ‘self and other’ (possibly already in interaction) and language. Such issues are apparent when we ‘switch’ languages and with then the way we name things and actions, and how beautifully ordinary such skills should be.[5] As Oona says of the library into which Bri is inducted: ‘You’ve no idea the doors that open when a word in one language crosses into another language, …’. And for Bri this enters into their fascination with understanding the life of a horse, for to assume horses have no language or capacity to name the things and actions of their worlds, Oona explains might be a deliberate act of humans because it makes it:

easier to control other creatures, or even peoples, us deciding that because we don’t know what they’re saying, what they’re saying doesn’t get to mean anything, or that they don’t get a say?

All of this leads to an examination of the words and syntax of the Latin motto of the school run by Oona for her community of social rebels against the society characterised by the ‘ Supera Bounder’, always drawing red lines around the things it wants to correct and take it into cold possession, like a teacher overly bound by the norms of one language of unitary naming and syntax. The motto is Facta sunt ipse verba. From the translation exercise she determines meanings that are in themselves multiple but which turn themselves into ways of saying ‘words are the stuff of stories (facts, deeds, acts and achievements) or vice versa (stories- namely facts, deeds, acts and achievements – are words). With dictionary in hand Bri does not stop there, for they substitute other rhyming words for ‘facta’ (pacta, iacta, tacta) to find ways or resolving words into thins that stories can do (make agreement on things, disturb or throw away the unsustainable fictions of life and touch or ‘hit’ us respectively). You have to read the storying of all this to get the right tone and playful beauty of this,[6]

But play is often serious, as in one fine illustration of what Oona says in the quotation above – the books almost buried but to me shining, reference to Palestine in our time, the iconic story of how some stories (from those without recognised power) are treated as ‘unverifiable’ against the dominant stories of the powerful. In explaining how ‘unverifiables’ come to be mentions in two sentences both the issues of the Ukrainian ‘war’ (deemed not a ‘war’ by Russian military might) and ‘genocide’ (deemed not a genocide in Gaza by Israeli might backed by the Supera Bounders of the West, the USA and UK, or for calling the actions of oil conglomerates the stuff of climate catastrophe and wanting the right to protest it, in ‘Stop Oil’ actions, (which sentence being long I don’t quote below):

All of the people living here, including the feral children, were right now unverifiables. They were largely unverifiable because of words. One person here had been unverified for saying out loud that a war was a war when it wasn’t permitted to call it a war. Another had found herself declared unverifiable for writing online that the killing of many people by another people was a genocide. ….

I will return to that horse but I think we need to realise how play with words as the stuff of stories structure the whole book, which is in three sections (named consecutively HORSE, POWER, LINES. Word play can man connections for both HORSEPOWER (as against machine power which steals the horse from itself and makes its an abstraction of a kind of energy) and POWERLINES, which are the means that social and governmental power imposes on the individuals who have stories. I have already indicated above however how a ‘horse’ in this story is central and becomes the focus of the stories it tells by being named Gliff, a homophone word for the word that indicates a legible mark – a word in basic language (that of hieroglyphics) a Glyph (to be the title of Ali Smith’s next novel next year.

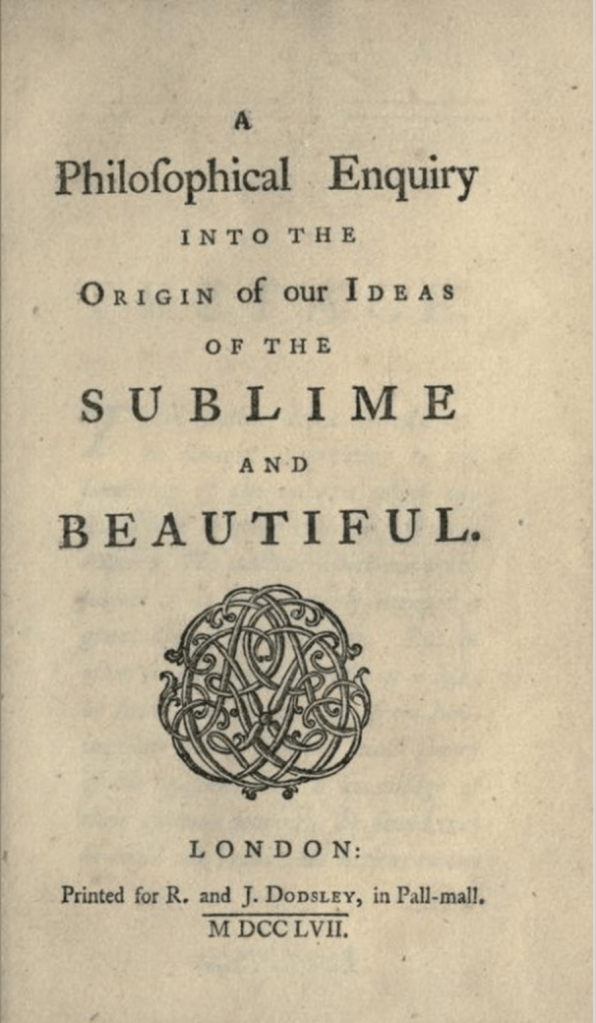

The word ‘gliff’ is defined in a short chapter with a variety of meanings from a variety of sources, including online urban dictionaries of unverifiable authority, quite purposely including: ‘A nonsense word. A misspelling of glyph. A substitute for any other word. A synonym for spliff’.[7] Dictionaries often aim to control and regulate attributions of meaning. Dr Samuel Johnson saw himself primarily in that role in aiming for a magisterial authority over the English language itself, which he explains in his Preface to the imposing Dictionary he produced in 1755:

When I took the first survey of my undertaking, I found our speech copious without order, and energetick (sic.) without rules: wherever I turned my view, there was perplexity to be disentangled, and confusion to be regulated; choice was to be made out of boundless variety, without any established principle of selection; adulterations were to be detected, without a settled test of purity; and modes of expression to be rejected or received, without the suffrages of any writers of classical reputation or acknowledged authority.[8]

Dictionary making is in short an act of verification, and the control of unverifiables is the essence of the intellectual, social and political society that the novel Gliff portrays. We have already seen above that the name / word gliff is aligned with the ‘unverifiable’ (the thing dictionaries oft aim to control) but is the icon of the uncontrollably ‘polysemous’ in the novel – a polysemous word/name is one of which the meanings are not only many but potentially infinite (‘a substitute for any other word’). Bri makes this point in praising Rose, despite Rose’s refusal to understand the point), though here she praises because she wants language to be free of control, quite unlike Dr. Johnson’s search for indubitable authority:

Polysemous. I looked that word up too. … //

And even one if its meanings is, here, see – a substitute for any other word

– you’ve given him a name that can stand in for, or represent, any other word, any word that exists. Or ever existed. Or will. Because of what you called him, he can be everything and anything. And at the same time his name can mean nothing at all. It’s like you both named him and let him be completely meaning-free![9]

The act of naming determines roles in stories provide the thing is not circled in red and made unverifiable by an authority willing to use its power that that be not so – as the society of the Supera Bounder in this novel does. Even the horse of the novel is bound in red when used as tool of power, even by rebels:

Ali Smith will remember the rule of the red pen in school work (I certainly too) – looking for and marking as clearly erroneous or unverifiable that that some authority, often unjustifiably, thinks to be the case. And the rule of this novel is to establish freedoms in the use of words and to expose in joy those that already exist. This is predominant, as in the fact that the horse in our navel is given the NAME Gliff in the act of naming anything, whether person by a ‘Proper Nouns’ as the used to be called or any other kind of noun naming a less verifiable thing, action or an abstraction, verbs or adjective, or the adventurous interactions between these grammatical terms. Sometimes the meanings lend themselves to strange metamorphosis – always in truth the way with language – such as the names of wild flowers (why we do we call them ‘wild’ – this is almost the same question as why we call a plant a ‘weed’ to distinguish it from one with verifiable status in the world of human naming).

More than two wild or ‘feral’ things run through the novel, but the strangest are stonecrop and campion. As wild flowers, they are confronted by Bri as they consult their mother’s ‘wildflower book’. Their unusual naming indicates in both cases irregularities in naming. These are either indicative of the thing named (stonecrop will ‘grow itself out of nothing’) or of its etymological history -is a campion a ‘champion’ in origin, and, if so, champion of what![10] The novel will not let go of ‘campion’.

In a chapter detailing Bri’s childish questions (represented only by a repeated single question mark between paragraphs of her mother’s remembered speech,) Bri’s mother explains how naming often represents and is associated with the fact that ‘people like to think they can control nature’ for the same sometimes merely of appearances or misunderstandings of the nature to which they names with wild or unregulated associations, like hornets. Among these are ‘lots of flowers that people like to think are weeds’, giving a list thereof ending in ‘,,, Stonecrop, Campion’. The last allows the mother’s speech to mention the folk history of the medical uses of campion in folklore.[11]

However later we come across appropriations of the term by people who resist the over-regulated society of Gliff’s fictive world. Ayesha Falcon, an unverifiable over in an Ark (Adult Retraining Centres) project, tells the story of her own capture by ‘security’ (the arm of social regulation and verification) only to then show that ‘security turned out to be the Campion, dressed up as security’ willing to allow her freedoms society have never otherwise allowed her and ‘were good people, good to me and they didn’t know me from Adam or Eve’.[12] She tells the story actually to her male ‘boss’ in the retraining plant to which she has been allocated, Allen Dale, who is Bri in their role as agent of government brainwashed into collusion (and verifiable masculinity as ‘he, Allen Dale’ not them, Bri) who too will be a figure of control, regulation and management security who hides a rebel like the Campion hides in plain sight acting what they know they are not.

Words are part of a game in this novel able to take on authorised meanings but be free to hold other ones less authorised, more free and more imaginative and human free usages. In the novel this is theorised as a system that regulates and monitors through surveillance that it regulates but fails to see some things – called ‘voids’ in the novel. The system needs the voids to explain the fact that it works by making people ‘disappear’ from social view but can deny it is doing this. Yet voids are places – like the dark stairwell in which Bri talks to Ayesha – are also places where escape from surveillance allows freedom to be plotted. It is why the Campion can appear to be ‘security’ but are not.

As a result there is much open word play in this novel even with nouns for abstractions – whose nature ought to be queried, like ‘security’ – security for whom and delivered in what way and in what circumstances. It is the play of Ali Smith plays that allows slippage into accidental meanings; meanings that free us from the mystifications of reality that authorities use words for. Let’s take two examples. The first relates to the first void in a systemic structure that we confront – the cracks between floorboards in a house, for these voids collect all manner of detritus from the continuum of lifes lived above the boards that show the complexity of people and what is really significant about them. The whole description works by a play on the ambiguity of the uses of the word ‘matter’ as noun or verb. Looking for the history related to the ex-railwayman’s cottage to which her mother’s partner Leif takes her, she starts exploring these ‘spaces between the boards’, spaces that lead to the ‘under-the-boards space’ which once uncovered would look like it contained what it looked like, ‘just dirt and grime’.

But you’d not just have DNA galore, you’d have the actual matter of what was left of those people and times. This his was a completely different sort of matter, the kind people say doesn’t matter when they talk about what history is.[13]

The play between noun and verb insists on a revision of the significance not just of a word but of lives, deaths and their interconnected, yet fragmented and forgotten, a significance ‘disappeared’ from history just like the history of migrants, working class people, LGBTQI+ (especially trans) people and women sometimes This is because authorities often decided that what ‘matters’ is the meanings that applies to own authorised interests and not to the interests of those of those dispossessed of power, status, homes, countries and recorded histories, truly the Many.

Another play occasions over the difficult physical and abstracts of the verb ‘render’. The wordplay starts as a result of Bri’s childlike (for they are a child at the time they are recalling) of their mother’s thoughts about her fate with the governance applied to her as an ‘unverifiable’:

Why are they trying to render us so temporary? Was something I’d hear our mother saying to Leif one night back in our old life.

That overheard thought opens up questions to Bri of the meaning of the verb ‘render’. Bri tries to piece together its meaning from the context of the conversation between Leif and their mother, only to look up the word on their laptop on the next morning. The meanings found vary from the description of the act of physical and industrial rendering, to description of moral actions or of making something or changing one thing into another, to its use in building work or in legal contracts. ‘It was always exciting to me the number of things a single word could mean’, but if polysemy was not enough for such learning Bri learns that context is oft what gives a clue to polysemic variation but that these contextual phrases using, say ‘render’ can too be polysemous./ Yet she must puzzle why her mother was talking about temporary rendering on the walls of her house, not yet having access to what her mother actually meant by ‘render temporary’.[14]

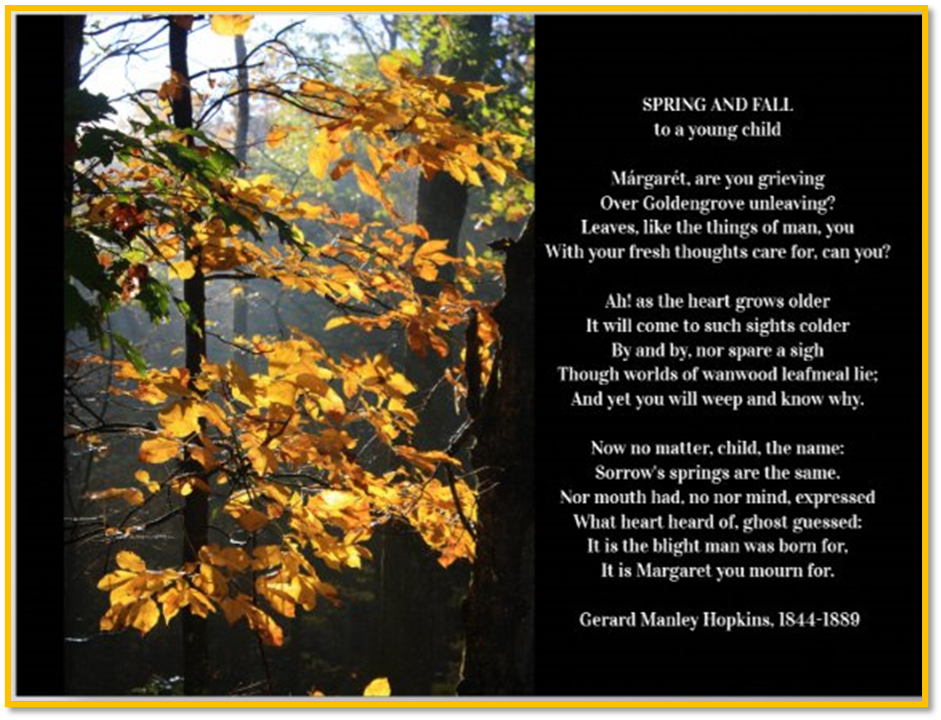

Yet the word’s polysemy can also open up the book’s means of referring to the emotional, a quality some critics find lacking together with distinct characterisation. Holly Williams in the i newspaper, for instance, says: ‘When so many characters within a book all seem to share the same aptitude for wordplay, they don’t feel fully differentiated’. I think this is a shallow reading because, since the book is mediated by the character Bri, it is unsurprising that they render characters in terms of their obsessions with words and polysemy, for the whole point is that emotion can only be differentiated between persons when the play around the words that might describe it is free and not bound to regulation. Polysemy is a deeper more explanatory trait in the book, after all, than a tendency as Williams sees it to pepper ‘with puns, and making hay with homonyms ‘ as if this were just a compulsive obsession of the writer. [15] For the term ‘puns’ I prefer that of homophones (words with same sound or sounds. Again I have a favourite relating to the Scandinavian character who is the partner of Rose and Bri’s mother called Leif. It is not, in a sense, a homophone we get in the novel and works indirectly through a false homophone in a famous poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins entitled Spring and Fall:

Márgarét, áre you gríeving Over Goldengrove unleaving? Leáves like the things of man, you With your fresh thoughts care for, can you? Ah! ás the heart grows older It will come to such sights colder By and by, nor spare a sigh Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie; And yet you wíll weep and know why. Now no matter, child, the name: Sórrow’s spríngs áre the same. Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed What heart heard of, ghost guessed: It ís the blight man was born for, It is Margaret you mourn for.

It is a poem about love and death, yes, but it plays with a false homonym between the action, expressed as a ‘leaving’ or ‘unleaving’ in a tree (spring and fall respectively) in a kind of neologism of natural activity that expresses life and death cycles, parting and encounter. Hopkins weaves it into a play on the role of basic human emotion, mourning for a loss of a true paradisaical undying and unchanging self in a world of ‘wanwood leafmeal’.

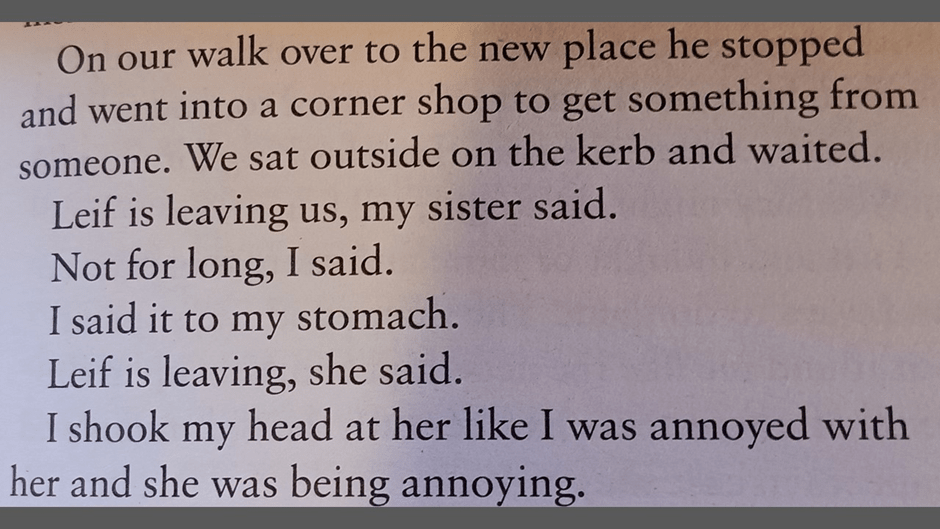

Many of the characters and situations in Gliff are about partings and meetings that lead to parings and the kind of world in which abandonment occurs almost as the rationale of progress (for some at least). It is a story of a world where disappearances occur – these can be a blessing and a curse and depend on a system that embraces absences (or ‘voids’ as mentioned before) in its own self-surveillance in order to allow disappearances to go on without notice. It is in such voids that hope lies, for they can be used to escape the system and are exploited by rebels to the system as well as the system itself. But because of the operation of the system, sometimes disappearances, parting and ‘leaving’ occurs without direct action by the system itself. The main example of this is the disappearance of Leif from Rose and Bri’s lives, and Smith uses her punning / homophonic writing to invite Hopkins into the emotional paradigms of loss in the book as a whole. In this episode Leif enters a ‘corner shop’ to buy provision as the children sit on the kerb and wait. It is an ideal moment to test Holly William’s assertion, and possibly the real reason I find her response superficial, that as a novel it ‘remains somewhat distant, it is also easier to admire it than be fully moved by it’:[16]

It still surprises me that anyone, especially anyone interested in art and professing a right to judge it, could believe that ‘distance’ is not often the medium in which emotion swims, even if it sometimes drowns there. The emotion here is built into the fact that partings and ‘leavings’ often has this feel to the one left behind, as they sit on some kerb kept outside of the decision about to break over them; sometimes, without them. knowing any process of decision is taking place. Yet even then, we talk to our stomach and its mass of neuronal connections to our feelings almost predictive of that fear. Absorbing the uncertainty of the truth that ‘he wouldn’t be back’ at all’ is exactly the same case as for Hopkin’s Margaret, grieving at an absence about to come or predictive: ‘Goldengrove unleaving’.

For children lost into the care system Holly Williams would seem even more superficial as calling this admirable but not ‘fully moving’. We might wonder if abandoned children, so many in this novel might ‘Leáves like the things of man, you / With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?’ Adults often wonder if children feel because they not express it all. Thus Holly Williams of Smith’s prose. The paradigm is not that of paradise against a fallen world but the longing for home in the face constant moving to escape misfortune. Into such patterns sad disappearances occur, even without the sci-fi machinery of this novel. I find it excruciatingly moving. And what moves me in essence, give or take an association or two to a famous poem that I do not believe it necessary to know, is the homophone of the NAME Leif and the word ‘leaf’ and its indirect relationship to the word ‘Leaves’ (plural leaves that are shed in autumn and an disappearance).

Nevertheless some of the disappearances are of the political kind that occur in occupied Palestinian remnant land and happened in Chile and Argentina, and to migrants now almost everywhere. Such is the case of Daisy, whom some unknown agency puts ‘in the back of their van and closed its doors and hey drove away’.[17] The same happens to Bri the narrator in their transition to the fully male, if fictive, Allan Dale.[18] Elicit disappearance begin to replace the system’s use of the Supera Bounder line-makers as Allan ages because they are an ‘obsolete methodology’, Disappearance is now done in a more concealed way the system’s agents refer to as ‘fence collect transfer’, the ‘new cooking-with-gas’. The fuller term is as ‘Fence collect transfer. Repurpose doze resell’. This is the story of modern capitalism indeed but also how power has always made the powerless feel to be disappearing, even when they haven’t, quite, yet: ‘The threatening look. The actual threat. The stony silence. The artistry and the discipline ti takes to humiliate. The laughing at someone, to their face then behind their back as they walk away. The swelling pleasure of seeing someone know to shrink away from you’. [19] I do not know how anyone could find that not moving, unless their sense of social entitlement id absolute – really or pretendedly.

The theme of disappearance gets merged in the novel with the pain associated with the masks persons wear to conceal or DISAPPEARED parts of their identity of which they are made to be ashamed by systems of governance; whether that be of political, social and emotional life. Even shame about being the victim of losses out of their control. Hence Bri’s dream, which she begins to tell To Ayesha Falcon, her employee, which is achingly emotional, of being ‘a kid, by myself, in an empty house’. Allan Dale tells the dream too because he feels that she has seen them, Bri and accompanying selves, beneath Allan dale’s mask:

I also don’t tell her how, since this morning when she was put on report and I saw her see me, the memory of something I thought had been permanently deleted from me has been steadily unfurling in a snag of bright green jagged stems so that I am right now having to set my whole self hard against anything bleeding in or out of me.[20]

My own feeling is that this complex image is that posed by an intersexual person but that would be to harden and rigidify the coding of sex/gender difference, so I won’t even justify that feeling. The issue here is that the self has been disappeared and is being to return to outward view despite itself. The disappeared self merges with the deleted self – for Allan Dale’s job is to ‘unverify’ people – remove verifiable details about suspect persons, but they (as Bri will find) can recover freedom of action from such deletion and escape from, as well as punishment by, the system. People are erased in many ways in this novel. The people who made ‘marks on walls’ in caves are deleted in themselves though the marks remain.[21] Bri near the end explains how ‘voids’ in the system are useful: ‘The CC system is shonky on purpose, to let people be disappeared.’[22] However, ‘erasure’ like disappearance can help rebels hide as well allow them to be evacuated from the system’s normative requirements on them and provisions for them. This is the point Bri’s mother makes when, from the past, a memory of her reminds Bri that to say too much will only show here why a system of surveillance, often covert, is called ‘a net.’ ‘Why do you think they call it a web?’. It captures your being unless you erase yourself from it.[23]

But the word-play and politics of connection between words and systemic meanings does not stop there. The book reminds us of how false invented homonyms where a word is misheard or misunderstood to create new meaning. Thus abattoir horses (of which Gliff was one such and under sentence of death- disappearance into slaughter) are heard of as ‘avatars’ by Rose and reinvented by the free and feral community to which they take Gliff, now named. The art term ‘still life’ is yoked into the theme of what makes life a thing that moves rather than impresses people you think need to be impressed in the ‘art hotel’ where Bri’s Mother works and that is yoke to play on a favourite echoed term (from Keats) by Smith, the idea of the still and stilled in art from The Ode On A Grecian Urn. The most moving passage of all on this theme is a riff on the many possible meanings of ‘still children’, whether as performatively so in art or in some process in time dynamics. I won’t quote it. It just has to be read.[24] It all means but you don’t in fact have to catch the associations to find this word play moving. One of the key near homophones important to the novel asks whether this novel is a puzzle or a means of emotional salvation: the play with the words ‘solve’ and ‘salve’ This is for each reader to decide upon.[25]

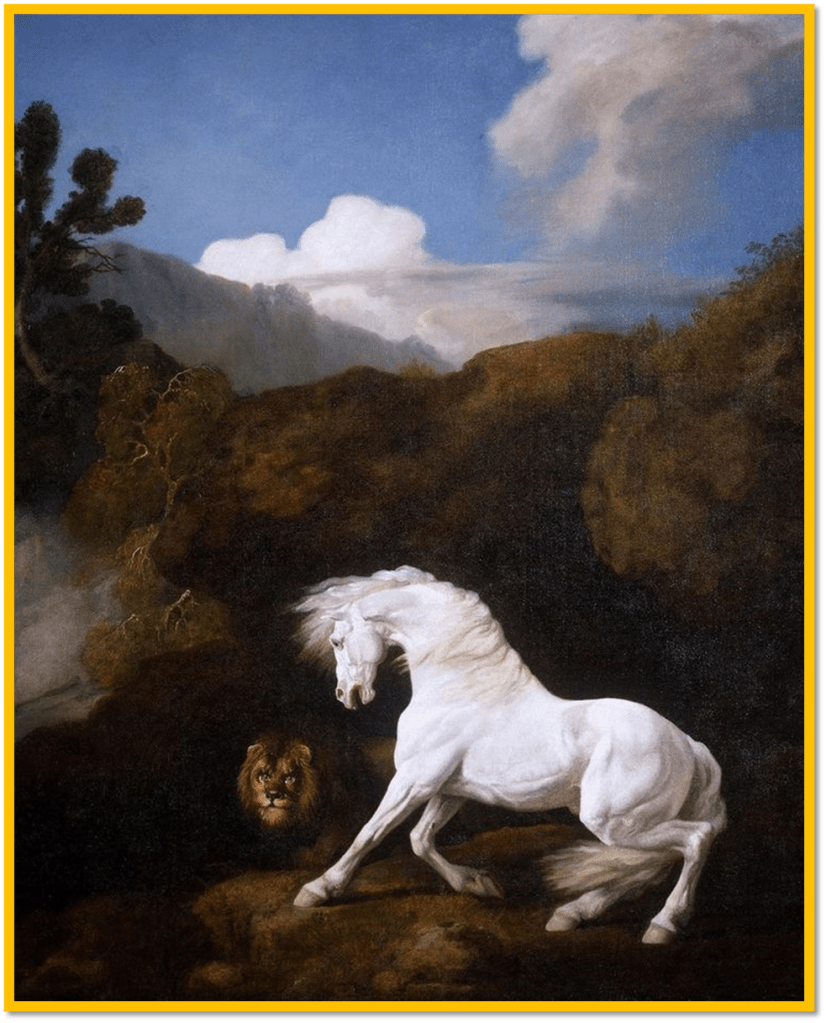

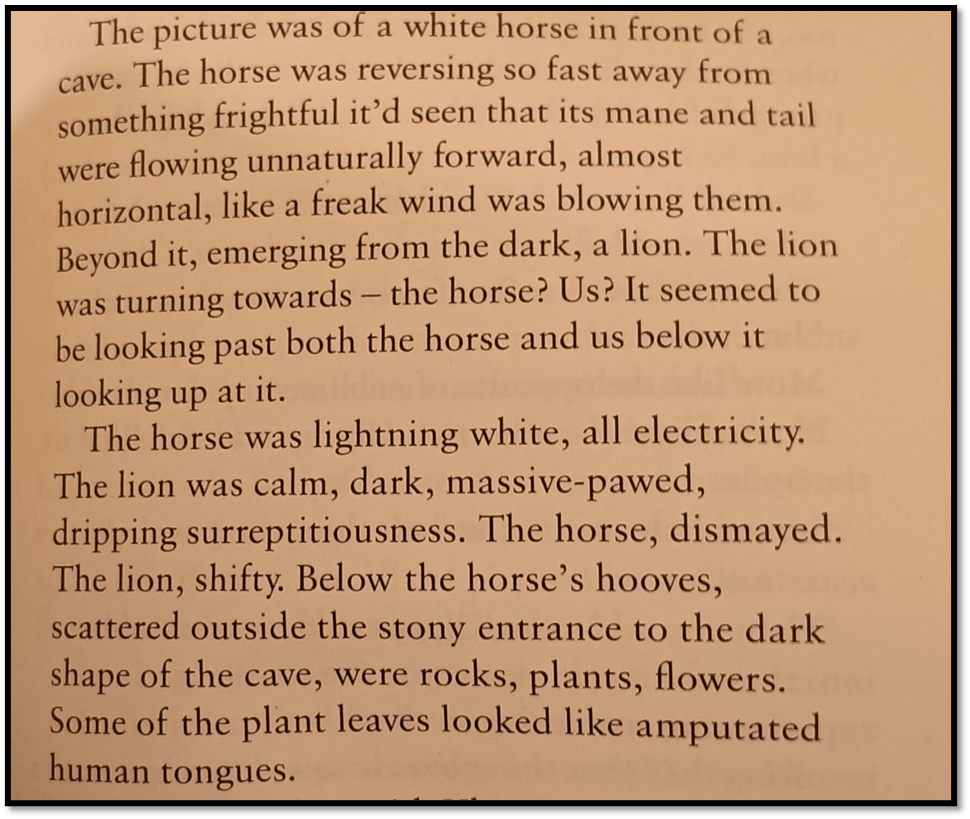

The turn against the artifice of still lifes gives impetus to a Romantic art of energy and passion, represented by discussions of the sublime, rather than the representational in art that revolves around the painting by George Stubbs (1770) ‘Horse frightened by a lion’.

The painting is captured in ekphrasis as Bri enters the community of rebels that had once been a sixth-form college and looked at this picture that was ‘hanging on the wall high above the hall’s stage’.[26] Here is the passage:[27]

The description is balanced between the notion of things stilled – either motionless or made silent (think of those ‘amputated tongues’) and the appearance of motion occurring (the horse) or predicted to about to occur (the lion). The theme of wild flowers is there too – as feral animal issues. There is a feel of Shelley’s Ode to the West Wind about it. The description leads on to a discussion of the representation of the eighteenth century notion (from Edmund Burke in 1757 of course) of The Sublime. The Sublime was an idea of Nature, in a theocratic sense , expressed not as beautiful, or ‘picturesque’ but as the awesome and fearful, if wonderful, expression of God’s power and wrath – associated with danger, Alpine scenery and the oncoming of te truly non-human into human life.

They discuss the cruelty Stubbs used to induce fear in the horse he got to model his painted one – a hose tethered to a ring and exposing it to fear (a stable boy making noises behind the horse it could not see the origin of). Rose, literal but beautiful ‘wants a new sublime’ where what is awe-inspiring is not cruel but liberatory – not based on the top-down power of artists like Stubbs and his stable boy but:

the horse that pulls that ring right out of that wall and tosses it about the air on its tether, I’ll be the horse chasing the stable boy to bite him in the back with my big horse teeth for scaring me because someone told him or paid him to do it. And then I’m off after that painter ….[28]

It seems just to rebel, for this horse is the model of Gliff the horse, against artists who use models of submission to state power as their theme, for as Ulyana, a chief of the unverifiables, says, the painting is based on a Roman model of ‘an allegory for accepting your own defeat as inevitable, and accepting it gracefully’.[29] And rebelling and not colluding (as an artist and a person in society) is exactly what – in my view – this book is about. I to refers to not only the masters and agents of power (for Stubbs is a bit of both – a rich landowner and patronised by the rich) but even the colluding persons who are in reality – like the stable-boy, because (as they see it) ‘someone told him or paid him to do it’.

This novel is timely because it bites the bullet of the hierarchical degrees of those who accept the injustice of Power from above, and embrace the ‘lines’ (often red ones) that it draws around the wild and the free and that called the ‘mad’. Bri and Rose’s mother was a partial rebel, Leif one who doesn’t quite measure up and Rose and Bri are two aspects of the rebel. Rose is fiercely literal, Bri, the one who will be led to collusion, until a later rebellion, as an agent of the Retraining Centres. The anger of Oona against the working class man who staffs the team handling the Supera bounder – that draws red lines around the things belonging to unverifiables – feels cruel , for after all, like the stable boy he is: ‘doing my job, … what I’m paid to’.[30] But how often do people say this in order to implement the cruel and over-rigid laws set by others. Even if you don’t believe it, to act in its name because you are ‘paid’ or bound to some hierarchical system, you have to accept responsibility for its evil. More so artists. And Ali Smith has spent a lifetime in art producing art that references whole histories of the artistic tradition in non-elitist ways and using them as a tool for resistance within them (as Shelley did). She is the ‘New Sublime’. To understand this, read over and over again the passage on the ‘voids’ from page 22 to page 223, which is wise about power and its processes of including you in its work, using its process to subvert it and the lines it draws, and on ‘lines’ themselves. That is the story after all in its subsections: Horse, Power, Lines.

I wanted to safe more about lines and bounds and the art that compares open and closed spaces within it and around it. But all of it is unverifiable, isn’t it?! And that is the point!

Love

Steven xxxxxx

[1] Ali Smith (2024: 159) Gliff Hamish Hamilton.

[2] Ibid: 213

[3] Ibid: 138

[4] ibid: 159.

[5] Ibid: 167

[6] All this section in ibid: 177 – 179. The Supera Bounder machine that characterises the red-line society can be found in increasingly threatening and powerful forms at ibid: 54, 63, 134, 199.

[7] Ibid: 180

[8] Samuel Johnson Preface To A Dictionary Of The English Language Available at: The Project Gutenberg eBook of Preface to a Dictionary of the English Language, by Samuel Johnson.

[9] Ali Smith 2024 op.cit: 183

[10] Ibid: 38

[11] Ibid: 79f.

[12] Ibid:237f.

[13] Ibid: 34

[14] You will need to read ibid: 66 – 68 to understand this better,

[15] Holly Williams (2024: 46) ‘Grave new world under surveillance’ in the i newspaper [Friday 18 October 2024] page 46.

[16] Holly Williams op.cit.

[17] Ali Smith op.cit: 192

[18] Ibid: 213

[19] Ibid: 227 – 229.

[20] (my italics) ibid: 235

[21] Ibid: 252

[22] Ibid; 262

[23] Ibid: 172

[24] Ibid: 37

[25] See ibid: 52, 273.

[26] Ibid: 110f.

[27] Ibid: 111

[28] Ibid: 114

[29] Ibid: 113

[30] Ibid; 54

3 thoughts on “‘Stop saying words, my sister whispered back. I want to hear the story’. This is a blog on Ali Smith (2024) ‘Gliff ‘.”