Do we guess when Detective St. John Strafford’s consciousness notices that there ‘was something odd about him today’ with regard a long standing character in the Quirke stories by Benjamin Black and the Quirke and Strafford stories of John Banville, Chief Inspector John Hackett, that Hackett is about to depart his place in the series forever?[1] Whether written by Benjamin Black or John Banville the continuities and disruptions of the lives of Quirke, Strafford and their families and associates matters as if it were a characteristic section of the history if the island of Ireland before and after it became divided by complex loyalties that are also animated by European history as a whole. This blog ponders on the latest John Banville crime novel: John Banville (2024) The Drowned London, Faber.

For other John Banviille ‘Quirke & Strafford’ novel blogs, use the links on these titles: Snow, April in Spain, The Lock-Up.

John Banville’s crime novels are usually well received though reviewed briefly, as his literary output never was. The critiques for the latter are often as ponderous as some of the novels but written with an awareness that his best (and for me that is Shroud) excuse any number of The Infinities and its like.

However, his crime novels are very different, although often there are references to the literary novels. In The Drowned Wymes childhood house, Wychwood, feels much like Birchwood, also the title of Banville’s acknowledged novel of Irish history. Strafford, when he hears of Wymes’ history, connects it to his own history, to the song Linden Lea and an apple tree: apples are a recurrent strange symbol in this novel. [2] Denton Wymes, a man with a criminal history of paedophilia but not of violence to children, is a character thereafter to whom Strafford maintains a commitment to being fair, a fairness Wymes finds nowhere else.

Of course Wymes matters too because the history of child abuse and its socio-cultural and institutional ramifications in Irish history matter in these novels from their launch by Banville’s Benjamin Black persona in the very first Quirke novel and have made many of the novels much more seriously dark than this is. In this novel, Strafford, at the end, even finds some empathy for Wymes, who abused as a child himself never replicates the horrors he suffers in quite the same way.

But there are other continuities and discontinuities in the lives of characters in these novels as a series that are further complicated in this one, including Quirke, Strafford, Phoebe (Quirke’s daughter). The subject of the first Quirke novel is the complications of her own knowledge of her parentage by Quirke. Hackett is central in all of them but dies in this one. A character from The Lock-Up, the academic historian Armitage, returns also to this novel, carrying with him all the references to both National Socialism in Germany and queerness, sometimes connected but not systemically except in tje mad imagining of the Nietschzean historian, Armitage. Armitage is in fact a serial psyopathic murderer of those women whom he feels betray him. There is almost no mystery in our discovery of this. It is clear from hints from the first chapter.

I say all this because for me The Drowned is neither as scary nor as thrilling as the last three (from Snow onwards) in its main plot but absolutely fascinating otherwise. What made me realise this was Laura Wilson’s brief review in The Guardian, where she ends her piece thus:

A beautifully written and intriguing slowburn of a book, in which the various quandaries in the main characters’ private lives are as absorbing as the central mystery.[3]

The only thing that gave me pause here when rereading the review was the reference to ‘the central mystery’ of the book, for I found it neither easy to entangle what is central as a mystery in the book, from other matters supposedly less central, nor to see it as a ‘mystery’ as such. The central stories involve two corpses who could be said to be drowned, though not with any great accuracy with regard to the second corpse, that of a child with autism and a learning disability.

The only mystery is how the stories get linked within one investigation and that mystery in truth interestingly reduces entirely into explanation by a series of contingent accidental meetings between Wymes, Armitage and the Ruddock family who have a holiday home near the site of a car wreck Wymes sees in a field in the first few chapters. Wymes finds an abandoned and wrecked Mercedes, belonging to Armitage and his missing wife in the middle of a field near the sea cliffs.

I sense little whodunnit value in any of this or the two possible murders. Centrality is the last of the issues – everything about the investigation contains and considers contingencies, often perpetuating patterns of possible crime from no evidence but instead from a great deal of prejudiced bias in the thinking of the characters, including those in those who are Garda (Irish police); patterns Armitage feels he can manipulate and fit together with his fantasies of universal queer Nazi psychology.

Wilson’s naming of the ‘the various quandaries in the main characters’ private lives’ is one way of seeing the sexual and romantic choices of Quirke, Strafford and Phoebe, but something in me feels these are not incidental but central to the continuities in the series of books, for these characters become more opaque in the involved and mysteriously motivated relationships they make. This is even so of attachments, even superficial ones like Strafford to Weyms, they make as the novels progress and the characters exchange the person, kind and intensity of their various inter-relationships and other relationships introduced between them.

Strafford is connected to Weyms through their upper-class Anglo-Irish Protestant background and the odd quirks (I use the term advisedly) that introduces into their relationships with others and with Ireland, both being deeply knotted into the country house politics of their origin and its crime novel genre equivalents, the stuff of the novel Snow. The fate of his relationship to Quirke’s daughter, Phoebe, is tied into queerly plotted relationship to Quirke himself as an unofficial ‘detective’ and dissector of the secrets of the the recent and the long-time dead.

Is this why Strafford is more forgiving of the sexual distortions that Weyms past has cast him into? And how does it explain his dependence on Phoebe’s love and his fear of being tied to her by fathering a baby, on whose death by miscarriage everyone relaxes into their weird status quo. Well, it would be status quo if Phoebe’s cosy cohabitation with her father wasn’t about to be disrupted by another woman in the final chapter, the stuff of the next novel presumably.

It is the unfinished nature of these sexual and romantic complications that renders a real-life backdrop to the intense sex-based murderousness of his central mysteries. In fact they are not mysterious as such but relationships usually covered up by societal conventions: those between love, hate, and the role of power in both, often power extending to extreme violence, but sometimes stopping short of that in the joy of inflicted pain on the other. This is so especially when a relationship to the other is mediated by the ambivalence of selves who both desire to cross boundaries and the repression of that desire into self-loathing. Let’s try and understand the strange meeting between Phoebe and Armitage in Chapter 19, mediated for both of them by obscure feelings about Strafford.

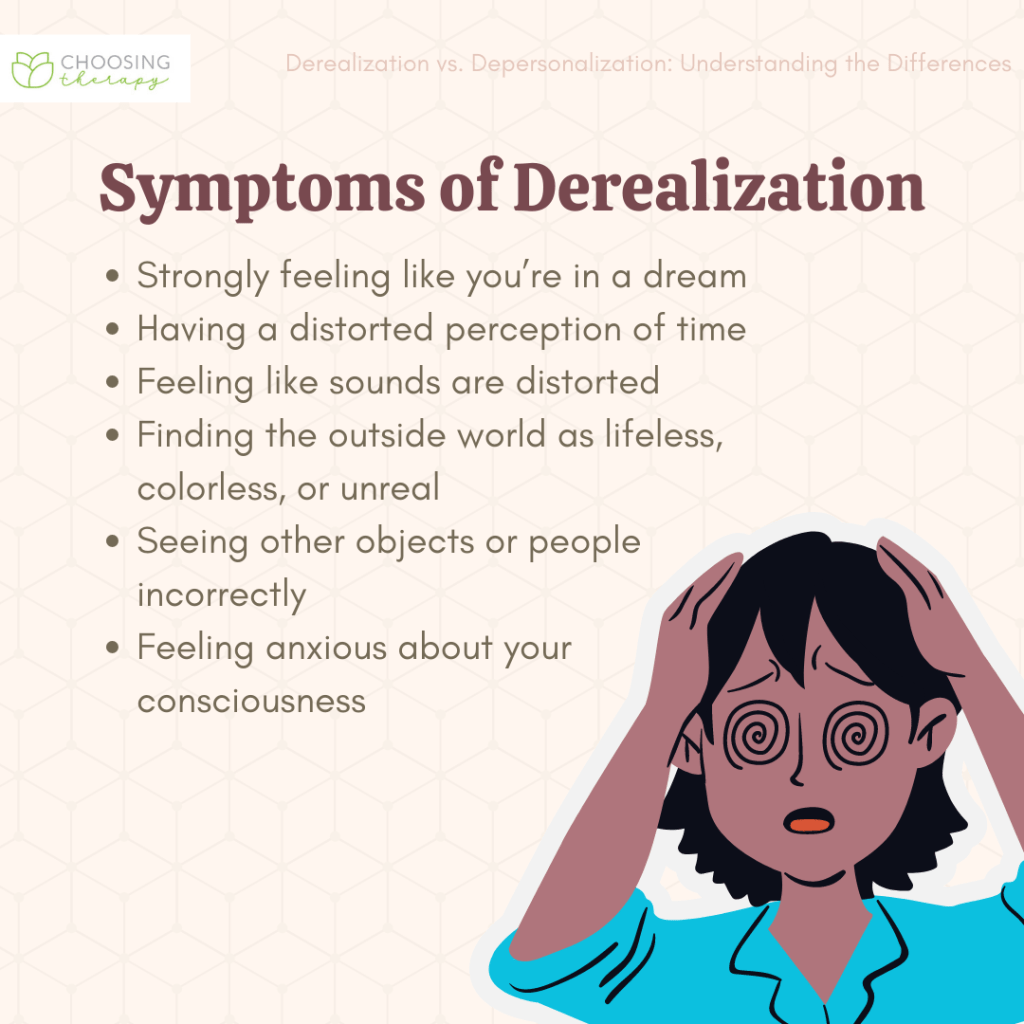

Armitage is a cold-blooded thing , but uncannily sexully alluring whilst being also disgusting: ‘she fixed again on those thin, mobile lips, moist and shiny and faintly reptilian’. She accepts an invitation to coffee nevertheless in which the queerness of the scapegoat Armitage had used for the murder of his last girlfriend, Rosa, is discussed, the son of a Nazi migrant. Frank Kessler. Phoebe, like it or not as readers is fixated with the murderous cool of Armitage: a fixation that is akin to a psychosomatic symptom but with the unreality of theatrical art – half symbol of the performances into which live resolves and a representation of psychological derealisation:

The sense of theatricality was growing stronger by the moment. Suddenly everything around her seemed a stage prop, the little round table, the dainty chairs they were sitting on, the gilding railing in front of them. Why was she here? And more to the point, why was he here? What did he want from her? She had a strong desire to get up and walk away from him, now, this second, never to see or hear of him again. And yet she couldn’t. [4]

Being fixed in time and space and being fixated are contingent emotional states here, both ambivalent in nature – where desire reaches into its opposite, as does its object from fascination to loathing. Indeed Banville makes this meeting a primal one – like that of the encounter between Eve and the serpent who will bring consciousness of desire for the alien (Catholics even lapsed ones like Quirke and Phoebe call it ‘sin’ and it has a fascination with the phallus that inevitably feels ‘horrid’ to the well-brought up): ‘What held her was a horrible fascination. This, she thought, must be what Eve felt like when the serpent came slithering out of the leaves of the forbidden tree and offered her an apple’. [5]

It is all very odd I think you will agree. It is rather more than Laura Wilson’s label signifies, ‘the various quandaries in the main characters’ private lives’, for quandaries do not have such deep fixated and fetishistic a quality as the lives of Banville’s central characters have, in their attraction to and distaste for the dead body – actually referenced in this book in the poste mortem of Deidre Armitage’s half-eaten and half-worn corpse when pulled from a Wexford bay.

And Strafford is the queerest fish of all – note the horrible fascination below, so equate with something vile in ‘male sweat’. This quality in male excrement evokes fearful desire to run away but no action of that kind:

I should get out of here, Strafford thought. The air in the room was still rancid with the smell of male sweat; it was if a noxious gas were seeping up from beneath the floorboards. [6]

The evocation of the experience of Nazi death camps reemerges here like a sore still running from the novel, The Lock-Up; but here associated with the unspoken thought that Charlie Ruddock might have had something to do with his disabled son’s disappearance, as a ‘burden’ too great for him, that was instead was being blamed, with no evidence, on the vulnerable Wymes and sexual motives.

And as for Hackett, he appears in this his final novel only to show that, even in novels, nothing is really continuous and unbroken in life. Strafford noticing that there ‘was something odd about him today’, leads to more news of Hackett’s physical symptoms that Strafford reads as an ontological issue for him, as if he was feeling existential challenge, which both as a living man and a fictional character in a series of novels, he is. Only at the end are these ontological issues rendered as physical symptoms.

There was something odd about him today. He seemed distracted – no, detached, that was the word. He was here, but his mind was elsewhere. There were brownish pouches under his eyes, and his forehead had a damp gleam. [7]

Eventually, the oddness becomes a physical state akin to the survivor of an escapist adventure romance, but a survivor doomed soon not to be:

Although he had steeled himself, still Quirke was shocked when he saw the state of Hackett. He seemed even more shrunken than he had in Ryan’s. He was sitting up in a big white bed like a lone survivor on a raft. He was wearing a pair of faded calico pyjamas with a blue stripe. A paper identity bracelet was fixed around his left wrist. His little shrivelled face had a chalky pallor, and the pink of his skull was visible through thin lank hair. When his visitors entered, Quirke first and Strafford after him, hats in their hands and preceded by a nurse, he looked at them as if he had no idea who they were. Perhaps he didn’t, Quirke thought. [8]

It is not just that Hackett thins and diminishes as a visible character. He loses all identity except that on a wristband and his co-characters equally lose all identity to him. Is he perhaps symbolic of the fact that even the supposed stalwarts of a novel series are dispensable elements to the ongoing process of exposing all the surviving remnant to events that will draw out yet more than their queer quirks. And we know that there are many more in Quirke and Strafford.

My own feeling is that continuity has something to do with Irish history, ever moving on, even if sometimes only into a regressive state. The series that Banville initiated in the role of his crime-writer nom de plume, Benjamin Black, has visited and revisited the scandals of sexual and physical abuse in the church and of the Magdalen laundries on the Catholic side of Ireland’s history. Strafford – introduced only when Banville took over from Black as crime-writer reprised much of the history of Protestant Anglo-Ireland. I have alluded to this in my first paragraph.

This history in Wymes is related in Chapter 11. It is the history of Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland, and the lesser families in it since the time of George II, a history of the decline of status and inherited wealth, a history valued by his mother but which he believes himself to have shamed. Strafford instead comes from the stock introduced even before Cromwell, and he is, he believes, the equivalent of the Spenser’s, Elizabeth I’s emissary to Ireland and court poet. There is in all this, taken with the history broken by the rigours of the Catholic Church in the Quirke wider family, these novel ought to be both continuous and fragmented, discontinuous for each line of people and families and for different reassons. For me, the death of Hackett is the symbol of all this discontinuity, now deeply set in the serial detective novel.

Each of the detective figures, Strafford in particular, are broken people – Strafford sleeps with a witness in his investigation, Charlotte Ruddock (‘in her husband’s house. in her child’s bed’), despite his promised marriage to Phoebe and oncoming parenthood as he believes at that point (not knowing of the miscarriage). The ethical level of the characters is extremely low. And thus for the sainted island of Ireland – it is a strange old history, as we saw in Sebastian Barry’s last fine novel (see link for a blog on this).

Bye for now. Still trying to fill in a blank mind while Geoff is in hospital

Much love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] John Banville (2024: 61) The Drowned London, Faber

[2] ibid: 165 – 166

[3] Laura Wilson (2024: 63) Crime and thrillers’ in The Guardian Saturday supplement 19th October 2024, 63.

[4] John Banville 2024 op,cit: 234

[5] ibid: 231

[6] ibid: 24

[7] ibid: 61

[8] ibid: 180-181