Alan Hollinghurst’s newest novel opens with the memoirist, who is the novel’s focus, Dave Win, thinking about his present life in his 80s. He is ‘two weeks into rehearsals for Bajazet at the Anvil’, where he is ‘playing old Acomat, the grand Vizier, a gift of a part, …’. This blog is a starter before I launch into a blog on Hollinghurst’s fabulous novel, hopefully tomorrow, but this play stuck in my mind because, in my library unread, I had a copy of Hollinghurst’s translation of Racine’s Bajazet, published in 1993 as Number 1 of a set called Chatto Playscripts and referring to the production of the play at the Almeida Theatre, London in November 1990. Hence, I’ve finally read it. Dave Win’s commentary on the play in the novel is brief and mainly concerns why the role of Acomat is so appealing for a man drawn to ‘big parts’ in the theatre (the joke is Dave’s in the novel, though using his performance as Mosca in Ben Jonson’s Volpone at Oxford University as its starting point). HE is being quizzed by Walt, a dear friend but a ‘straight’ one:

‘”Do you have a big part?”

“Huge,” I said. We both smiled and looked away as we let the joke escape.

Alan Hollinghurst (2024: 208f.) Our Evenings London & Dublin, Picador.

Acomat appeals because he has ‘six pages of blank verse in the first ten minutes – complicated stuff about plots, armies, and empires which the audience, in their first eager ignorance, will take in intently, knowing their evening depends on it’ (ibid: 4). There is that in Dave that loves holding an audience by whatever means but he also likes the present role because he plays it alongside Keith Mackle playing the vizier’s confidant’, Osmin. Mackle is a young mixed-race (Glasgow, Ghana) actor, just as Dave is an older mixed-race actor. Dave says Keith ‘reminds me of Hector in his handsomeness and concentration’ and because he is patient with Dave’s failing memory and the mistakes it leads to. Hector, by the way, is an old lover and co-actor, memories of whom we hear much later.

There isn’t much to pin this down to being a transposed memory of Hollinghurst’s own translation of Bajazet that Dave is acting in. However. Dave says to us, as cited above already, that the speeches he delivers are in blank verse. In his ‘Translator’s Note’, Hollinghurst says that he deliberately avoided the use of rhyming metrical alexandrines in Racine’s seventeenth-century Court French as being not natural to British actors; as they definitively are to French ones: ‘Blank verse was the inevitable solution; …’, and without rhyme

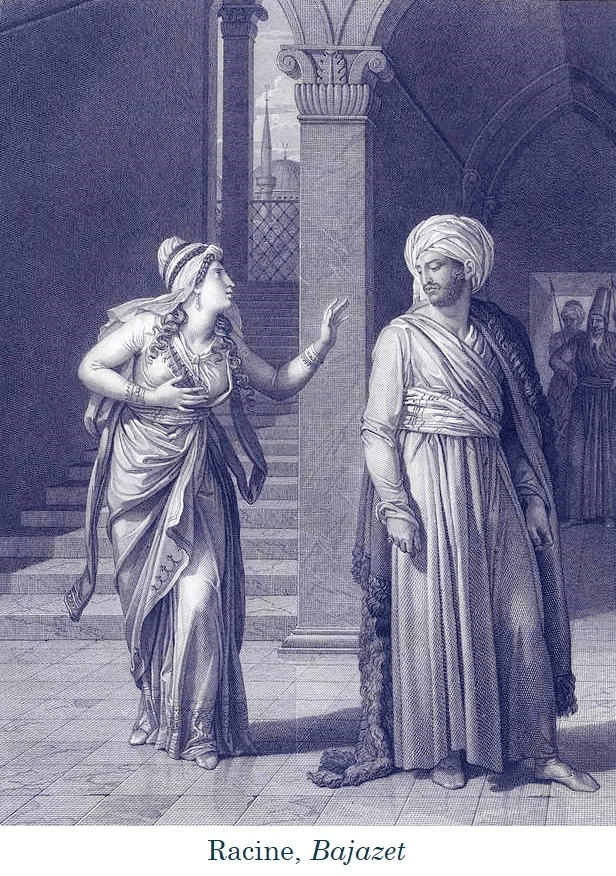

Why, other than for a private joke, might Hollinghurst point to Bajazet thus. Of course there is the chance to show that the old man’s attraction to young mixed-race actors remains and that he feels some excitement in this production of acting without the pretence of colour-blindness adopted throughout his life by august institutions at the time like The Royal Shakespeare Company, who banish him to small parts for that unacknowledged reason. There is also the fact that in this play there is an oddness in its treatment of sex/gender. In his Second Preface of 1676, as translated by Hollinghurst, Racine suggests that he carefully distinguishes between the type of ‘love’ professed by women which resembles, he implicitly and wickedly suggests in his ironies, any other court in the world even without suggesting these courts are also a ‘harem’ (by which sleight of hand he chiefly refers to, I think, Bourbon Versailles of course), from that of men:

Indeed, is there any court in the world where jealousy and love can be better known than in a place where so many rivals are shut in together, and where all the women have no other study, in their unending idleness, than that of learning to please and be loved? The men there probably do not love with the same refinement.

Racine [1990: xv] (trans Alan Hollinghurst) Bajazet London, Chatto & Windus

Certainly Acomat has no truck with the love of women which he calls the ‘low apprenticeship of love’. He is drawn to Atalide, not by anything but that she is of the royal line and will be a string to his bow of power, should (as he expects) Bajazet, once having been made Sultan by Acomat, turn against him (ibid: 11f.). His attitude to Osmin, played by the lovely Keith Mackle for Dave, whose adoration for him – young man to older one – is much more living and demanding. He tests Osmin’s love for him just as much as do the regent Sultaness Roxane and Atalide the love of Bajazet for each of them set with, or against, his love of earthy dominion as Sultan-to-be, should his coup d’etat achieve its ends.

ACOMAT: Will you be with me fearless to the end? OSMIN: My lord, you slight me: if you die, I die. ACOMAT: .... / .... Let's die: I as vizier, and you Dear Osmin, as a vizier's favourite. (ibid: 60)

One can only imagine how Dave Win played this protestation to his ‘favourite’ beyond the love of women. Is Racine’s final irony that the love between men, far from being less refined, is more so, so locked in are the latter with ‘in their unending idleness …learning to please and be loved’? But in truth there is no textual justification that Hollinghurst used his earlier translation thus, nor that Dave Win is testing his lovers – whether as mothers and mother-figures, fathers or father -figures (the first for him is only a photograph of uncertain validity and reliability) or his series of lovers locked in ‘our evenings’, whatever that variously means to them.

But one feature of Bajazet is extremely interesting. Interviewed by GQ magazine prior to publication, Hollinghurst is asked about his decision to choose a mixed-race queer narrator and memoirist as his subject. He says to Alim Kheraj:

The idea from the start was that Dave would be trained up to be this exemplary Englishman and any little hints or possible openings into exploring his colonial heritage are very slight and rather discouraged because of very complex problems – the shame, the partial ostracism and everything that his mother has had to go through as a single parent of a mixed-race child. Obviously, I’m free to do anything like that as a creative artist, but the whole question of writing from another racial perspective, of course, became so politicised over the years in which I was planning and writing the book. That made me the more sensitive to the possible pitfalls of doing it.

Alim Kheraj (2024) ‘Interview: Alan Hollinghurst on Our Evenings, his most daring and political novel yet’ in GQ Magazine [online] (7 October 2024) available at: https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/alan-hollinghurst-our-evenings-interview#:~:text=Our%20Evenings.%20,%20his%20most%20daring%20and%20political%20novel%20yet

What fascinates is clearly the experience of an identity as half-Burmese repressed by complex social forces experienced by him directly and through his mother. He knows of course that he is on sticky ground politically – as an entitled middle-class white man he may merely ‘appropriate’ and/or colonise an identity of which he has no direct knowledge or interest (at least known in public) of representing this order of being accurately and fairly. In the process, as unfortunately even in E.M.Forster’s great A Passage to India (though this novel so understands what it is doing and remains a classic of the genre) it is possible to merely further abuse a marginalised people, using them to illustrate the stuff of white cultural obsessions and misrepresenting, exoticising or even , portraying negatively or in stereotypes the culture of the ‘other’.

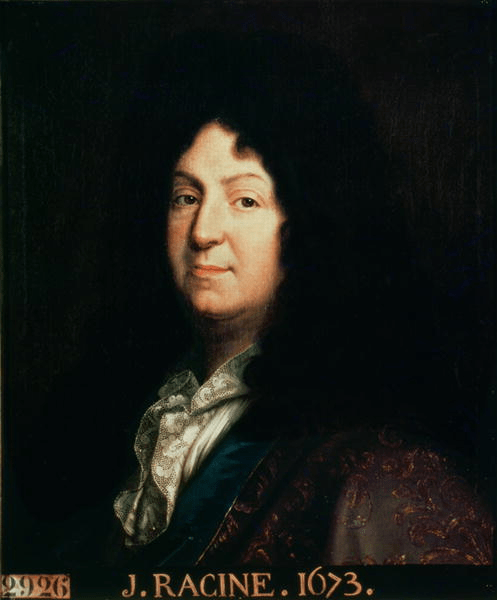

I need to think about all this before I write on Our Evenings, but it is worth noting that Racine faced a similar issue in representing the Ottoman Turkish court in the city he would only call Byzantium [not even Constantinople to say nothing of Istanbul], an insult to Turks of the time. In his first Preface he says his ‘main principle’ is ‘to change nothing of the morals and customs of the nation’ and boasts of his research on the matter (ibid: xi). In the second Preface the phrase he uses at a parallel movement changes for he speaks of the ‘morals and wisdom of the Turks’ (my emphasis – ibid: xv).

Is there a hint here of Hollinghurst’s more contemporary attempt to look at human difference in a more intersected environment than white queer men alone, as in The Line Of Beauty, where class is the issue of otherness contrasted with growing up queer. Racine notes that the events he dramatises are very near in time to that of his own world and that he would never have written thus of such temporally close events had they been in France.For him the ignorance of his audience to the affairs of the Turks was much the same as that of the ancients and/or historical world and thus allowed for the degree of fiction demanded by the genre of tragedy, and citing Tacitus:

One could say that the respect we have for heroes increases in proportion to their remoteness from us: major e longinquo reverentia. The remoteness of the country to some extent makes good the excessive closeness of the events in time: for if I may say so, people scarcely distinguish between what is a thousand years and what a thousand leagues from them. Thus it is that Turkish people, for example, however modern they may be, have a dignity upon our stage. one sees them as ancients before their time. (ibid: xiv)

Of course, the issue is different in a global twenty-first century but ignorance about Burma / Myanmar is so oft a feature of the novel as is the querying of the reasons that Dave mother’s bore him without a father, reasons that never get stated but are continually the subject of speculation, either as gossip or, for Dave, more integrally. The construction of alienating distance on ‘our stage’ is a definitive theme of Our Evenings as it is in in other public performances, so called in the novel, other than on the stage – in the organisation and social interactions of schools, hotels and different kinds of home for instance. Those homes range from those of extreme wealth (like Woolpeck owned by the rich Hadlows) downwards in monetary status. It is a novel of more recent times – the Brexit events and Covid epidemic. Hoeever. when asked about this Hollinghurst told Kheraj that: ‘What I was most imaginatively involved with, though, was the things further back’. This idea of things distant in time, and, in this novel, space – a space never entered and a colonial space, is vital in Our Evenings but I am not sure yet why.

This is all to go in the mix as I think about the novel today, but, for now, I am rather pleased I have read Bajazet.

With all my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx

2 thoughts on “A note about ‘Bajazet’ by Racine and translated by Alan Hollinghurst and featuring in ‘Our Evenings’”