I queue in a local One-Stop every Saturday because it is the only place I can use my Saturday only pre-paid collection card for The Guardian. Shops like this have garish counters now, festooned with various kinds of prize lottery tickets, each numbered and behind it an assistant who acts to sell these and pay out out on winnings, when these are minimal, as most often they are.

I sometimes wonder about the kind of purchase being made here, as if these tickets represented some desire that cannot be met by the goods bought but by some huge wish those goods represent, and which being disappointed in that wish, or successful in some way that promises to pay you off for maintaining the hope built into their sales rhetoric, become mere trash thrown on the ground around the Street – in my town the street is called Hope Street, presumably a hang-on from Methodism in Northern mining towns.

You could gauge the queue not by its length – although often formidable in that respect alone – but by the expressive intensities of the desire within it to be be included in a means of changing one’s ‘lot’ into one more aligned to dreams and wish fulfillment: for some represented by a chance to stabilise their lives by wealth that might be invested or buy an asset that either houses and feeds them, for others a chance to meet their fantasies of high living. Sometimes I suspect, those poorest in worldly wealth are the most driven by fantasy, by wishful desire, partly because the chances of great fortune are minimal. These people are the target of the phrase used by one lottery – I think the Postcode Lottery – that you have ‘to be in it to win it’. What this phrase emphases is not only the wishful aspect of ‘winning’ (of success in a venture) but the ease of achieving that aim – you merely have to be ‘in it’, and to be ‘in it’ costs relatively little. In fact that phrase ‘in it’, is even more pernicious, for it promises a community in ‘it’, being one of the many – a strange addition to the wish of the dispossessed , for it is precisely because so many are ‘in it’ that one’s chances statistically diminish.

If I dream I have ‘won’ the lottery, I dream of a fortune cascading down on me, like that of Zeus on Danaë, what looks, and damages the skin, like solid gold so far descending would but is in fact the seminal product of a godly desire that will birth from me, in the myth Perseus, but in life, a new life-chance with what my winnings are, one far beyond expression and as fabulous of the heroic story of Perseus. And some respondents to this question will be planning what they would do with such fabulous thrilling selection by a God. Was it always like this when we set our hopes on winning. Part of the answer might lie in the etymological history of the verb ‘to win’, here briefly told by etymonline.com:

win (verb): “be successful or victorious” in a game, contest, or battle, c. 1300, winnen, a fusion of Old English winnan “to labor, toil, struggle for, work at; contend, fight,” and gewinnan “to gain or succeed by struggling, conquer, obtain.” Both are from Proto-Germanic *wennanan “to seek to gain,” which is reconstructed to be from PIE root *wen- (1) “to desire, strive for,” which Boutkan calls “a clearly reconstructable root with different semantic developments,” but probably originally “want,” hence “try to obtain.”

The sense of “exert effort” in early Middle English faded into “earn (things of value) through effort” (c. 1300) but lingers in breadwinner. For sense evolution from “work for” to “obtain,” compare get, gain.

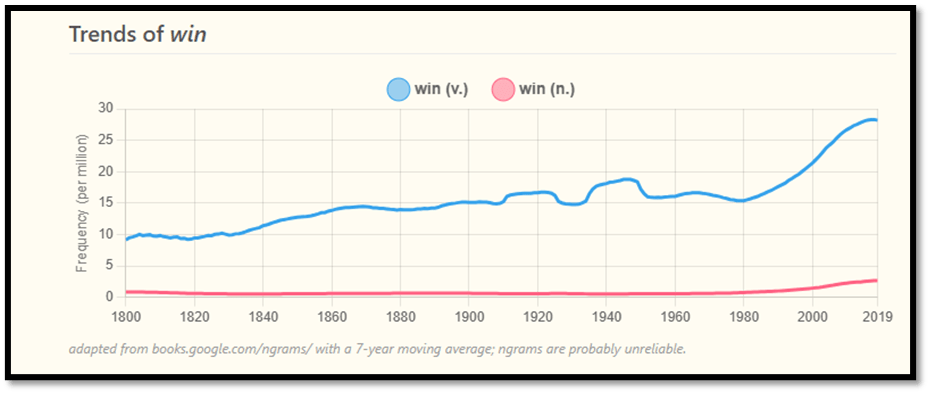

Perhaps also trends in the use of the verb ‘win’ (the blue line in the graph) tell the story in part, compared with the trends in the noun (the red line). After all, yo talk of a win, or the win, presupposes the existence of a win in some form ( a cheque or a letter even if not the valuable monetary asset (gold for instance) per se), to talk of ‘winning’ in no way presupposes that existence, exceopt in thoughts and / or imagination. As unregulated capitalism and the commodification of desire takes hold even in the masses up to near the present day, 2019 – though the line is stabilising).

The key, though, to reading this etymological history with significance is the evidence in it of the deterioration of the link of the verb ‘to win’ to its sinification of a goal won by the exertion of effort. Because you have to be more than ‘in it’ to win anything that requires exertion, you have to be capable of a degree of exertion that raises one beyond the ordinary. It might be the exertion of Perseus winning the hand of Andromeda by killing a ferocious sea-dragon,not just the passivity of Danaë showered by Zeus’ golden semen, in order to birth Perseus (though no doubt the exertion in birth made up for it, but by then, as it were, she had already won the God’s favour, in so far as he was capable of favouring another than himself).

The modern meaning of ‘win’ seems to have faded yet further from the assumption that we work hard, even by heroic or ‘Herculean’ proportions, for our goals in life in ‘in it to win it’. The effort of being ‘in it’, no greater than standing in the queue in One-Stop with cash enough to purchase a ticket, is so minimal, the publicity for lotteries determine it to be negligible at the level of the individual (although that is not always truly the case). Meanwhile, the same publicity pumps at the elevation of desire to absurd heights. Prompt questions like this one likewise aim to release desire, possibly with a desire to differentiate wise for foolish virgins by grading the quality of their visionary dreams: the wise dreaming of investing for the aim of unrealistic stability in life, the foolish dreaming of a surplus of even more unrealistic infinite and unending consumption.

For this reason, I do not buy lottery tickets. This is not because I do not dream, fantasise, or engage in magical thinking in other ways, for even working hard to achieve something involves magical thinking about the nature of one’s readiness for the work, but because the basis of lottery dreams are dissatisfaction with one’s lot (Anglo-Saxon hlot) and an over-readiness to attribute one’s dissatisfaction to having insufficiently appeased and grovelled to some Higher Power, whether fate, destiny, the Greek Gods or the Judaeo-Christian monolithic God. [1]

The idea of a contemplating g one’s lot in life is already impregnated with magical thinking, since most religions presumptive each person’s allotment of good or evil fortune, the province of God’s, or short of that ‘luck’, with a factor in between where sit semi-divine Norns or Fates. The idea of a national lottery is the same idea writ small. Hence, the appeal of lotteries to low paid or unpaid citizens like the new opium of the masses, struggling to survive, but refusing to take their political destiny in their hands. As the fodder too of a politically tight wing movement like Reform, too, they are so because political choices appear to them no more than a gamble. It is a model of thinking that suits the parties of the status quo, for communal change is the one kind of change that is not gained except by hard committed work. It is a hope not now represented by workerism with its love of growth econom8cs, nor top-down pragmatism ever tak8ng the moderate centre righthand like the present government. It is a harder job based on facing the hard facts of environmental degradation in all domains and reversing them. A Green government would have to do this.

All for now

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

______________________________

[1] ‘Old English hlot “object used to determine someone’s share” (anything from dice to straw, but often a chip of wood with a name inscribed on it), also “what falls to a person by lot,” from Proto-Germanic *khlutom (source also of Old Norse hlutr “lot, share,” Old Frisian hlot “lot,” Old Saxon hlot, Middle Dutch, Dutch lot, Old High German hluz “share of land,” German Los), from a strong verb (the source of Old English hleotan “to cast lots, obtain by lot; to foretell”). The whole group is of unknown origin’. [https://www.etymonline.com/word/lot]