Worthwhile modern readings which root Peter Grimes in the experience of Benjamin Britten as a queer man may be available, although I think Phillip Brett’s Cambridge monograph on the opera may have served as a last word on why it both requires that perspective and why it is insufficient to provide a satisfactory reading on its own, or to make queer men content to see the opera as a commentary on our experience, historical or otherwise.

I have taken an interest in Peter Grimes because I have booked to see Opera North’s production of it at the Theatre Royal Newcastle in March with dear friend Catherine. I have already written on it based on a reading of Letter XXII, containing Crabbe’s version of Grimes’ story, of The Borough by George Crabbe on which, in part, the opera was very loosely based, together with other character’s stories, including that of Ellen Orford, and the Introduction which tells of the everyday in Aldeburgh, the poem’s setting. Read that blog at this link if you wish.

Phillip Brett’s critical work on the opera represented within the Cambridge Companion is superlative, as is his attempt to honestly represent a debate on the quality of the opera on which he is on the favourable side. Brett’s position is a highly nuanced one. He reflects that the opera certainly was born of the experience of himself and his partner, Peter Pear’s experience of generalised homophobia, linked to suspicion of their status as conscientious objectors. In early drafts of the narrative design of the work, there are even clear elements that render Grimes’ relationships to the workhouse boys he employs tinged with one-way sexual desire for the boys, even if of a highly suppressed sort.

However, Brett makes it clear in his final postscript that Britten, whilst allowing in this material in the drafts, possibly at Peter Pear’s prompting, was unwilling to allow it to stay in later drafts. Likewise, he eradicated much of the material a out Grimes relationship to his eponymous father, which might, Brett thinks, have weighted the interpretation to a psychodynamic Freudian one. In both cases, Brett believes Britten wanted to examine how a very ordinary fisherman, accustomed to.udolation with only stars and sea for company, can become an outcast and scapegoat for the ills of society.

He says this, despite having mounted in the chapter preceding his book’s epilogue, a very superior argument about how very ordinary men were indeed the outcast and scapegoated as the cause of social, political and military ills and deficits in British manhood, solely because they were queer. Brett says:

Peter Grimes is about a man who is persecuted because he is different. We may recall Peter Pears’s explanation that Grimes “is very much of an ordinary weak person who…offends against the conventional code, is classed by society as a criminal and destroyed as such”. To which he adds as a final line, “There are plenty of Grimeses around still, I think!” There is every reason to believe that the unspoken matter is what in 1945 was still the crime that hardly dare speak its name, and that it is to the homosexual condition that Peter Grimes is addressed. (Brett, 1983, p. 187)

Despite the lack of any hint in fact in the extant opera that Grimes has a sexual interest in boys or men, it is likely however that the stigmatised situation of queer men was at least partly Britten’s and Pear’s motivation in building the piece. However, Montagu Slater, the Peter Grimes librettist, though he refused to understand why Britten and Pears, like Auden and Isherwood, fled Britain before the start of a war clearly felt the ‘difference in Peter Grimes was much more about a kind of poetic and political idealism akin to the Byronic hero. Slater, a confirmed Communist, felt his affiliation to Britten was on the level of shared political values that aimed to change society for the better. However, little even of that motivation for difference survives, even in the libretto alone. There are only two moments in which such idealism could be inferred, however generalised the articulation of these ideals. Only the retired skipper Balstrode has any sympathy for Grimes in the Borough but Grimes tells him that he feels that his difference to hem is only related to the fact that only he is not entirely motivated by the cash nexus, as Thoms Carlyle called it, the self-interest of the get-rich trader. As far as Grimes is concerned, the Borough residents lack vision and dreams, such as he has – visions that he calls ‘fiery’ and which are possibly revolutionary at a stretch, although they relate also to an ambition that could be purely personal (who can know – for Grimes does not elaborate them). Instead he capitulates to the values of the Borough. If they only ‘listen to money’, he will get money to ‘win them over’, as if his purpose might be political conversion or merely finding himself a place in their society. Here is the exchange with Bulstrode from near the end of Act One 1 Scene 1:

Peter: They listen to money

These Borough gossips

I have my visions

Fiery visions.

They call me dreamer

They scoff at my dreams

And my ambition.

But I know a way

To answer the Borough

I’ll win them over.

Balstrode: With the new prentice?

Peter: We’ll sail together.

These Borough gossips

Listen to money

Only to money:

I’ll fish the sea dry,

Sell the good catches–

That wealthy merchant

Grimes will set up

Household and shop

You will all see it!

I’ll marry Ellen!

Balstrode: Man – go and ask her

Without your booty,

She’ll have you now.

Peter: No – not for pity!…

Balstrode: Then the old tragedy

Is in store:

New start with new prentice

Just as before.

Peter: What Peter Grimes decides

Is his affair.

Balstrode: You fool, man, fool!

Grimes’s visions and dreams remain unspoken, what is articulated only is his conviction that he can succeed better than the community at the same money games as interest hem, becoming a rich married bourgeois merchant. Balstrode neither asks about the ‘fiery visions’ nor the alternate dream of bourgeois security. All he picks out of Grimes’ talk is that he wants eventually to marry Ellen Orford. Given that this ‘ambition’ is conventional and heteronormative, Balstrade cuts short talk of Grimes story of dreams and tells him to marry Helen straight away (only the final line of his ambition), asserting she is willing for that (which appears to be the case). Thence, we get Grimes’ resistance. He doubts Helen would marry him now other than for pity of him. She too needs to be impressed by the Grimes to come – the rich merchant. The clues here are rich. If Grimes is ‘different’, it is basically a difference based on the fact that he does not wish to be thought a man whose dreams can be understood in fullness, and that only he will know when they are in readiness for some kind of achieved fulfillment: ‘What Peter Grimes decides / Is his affair’, and cannot be comprehended by others.

Grimes is frequently seen as being as unpopular in his community as that early talk suggests. In Act 1, Scene 3, he for the first, and only time talks like a poetic visionary before an uncomprehending Borough audience in The Boar Inn where the Borough rests from trade with some very poly-amorous prostitutes managed by the pub’s landlady, which ‘Auntie’ names her ‘Nieces’. No-one is speakig, shocked by Peter’s sudden appearance at a place he does not usually attend:

(No-one answers. Silence is broken by Peter, as if thinking aloud.)

Peter: Now the great Bear and Pleiades

where earth moves

Are drawing up the clouds

of human grief

Breathing solemnity in the deep night.

Who can decipher

In storm or starlight

The written character

of a friendly fate –

As the sky turns, the world for us to change?

But if the horoscope's

bewildering

Like a flashing turmoil

of a shoal of herring,

Who can turn skies back and begin again?

(Silence again. Then muttering in undertones.)

Chorus: He’s mad or drunk.

Why's that man here?

Nieces: His song alone would sour the beer.

Chorus: His temper’s up.

O chuck him out.

Nieces: I wouldn’t mind if he didn’t howl.

Chorus: He looks as though he’s nearly drowned.

Boles (staggers up to Grimes): You’ve sold your soul, Grimes.

Balstrode: Come away.

Boles: Satan’s got no hold on me.

Balstrode: Leave him alone, you drunkard.

Again, the language is vague, but the generalised desire for a kind of universal change in the world is mooted vaguely. Indeed the topic of this speech appears to be the fact that what happens to ‘the earth’, and the misty volume of human grief in it is impossible to read (for we read what is ‘written’ without illumination) what the world ‘for us to change’ wants of us, or predict its future in phenomena which look to human eyes as chaotic as the appearance of a ‘flashing turmoil / of a shoal of herring’.

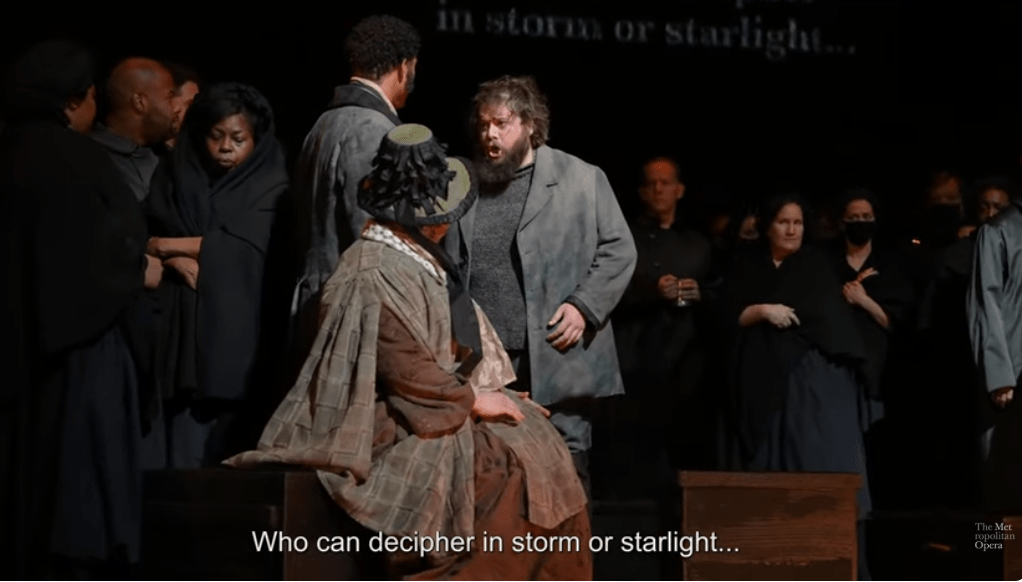

Peter is helpless and clueless but nevertheless still feels he is ‘different’ in both dream and vision: after all, he will later tell us, in Scene 2 of the same Act, that he ‘can see / The shoals to which the rest are blind’. Does his visionary Byronic heroism again come down to the size of the catches he can aim at as a fisherman and for whom the boys in his employ die. Some productions use the grandiose inarticulate to suggest that Peter wants someone in his community to be able to read clearly in him that which is obscure to him, however hards he tries to decipher the characters of his individual destiny. In John Doyle’s production for the Metropolitan Opera New York, Adam Clayton as Grimes (below) seems desperate to engage someone, passing between borough residents but receiving no adequate response.

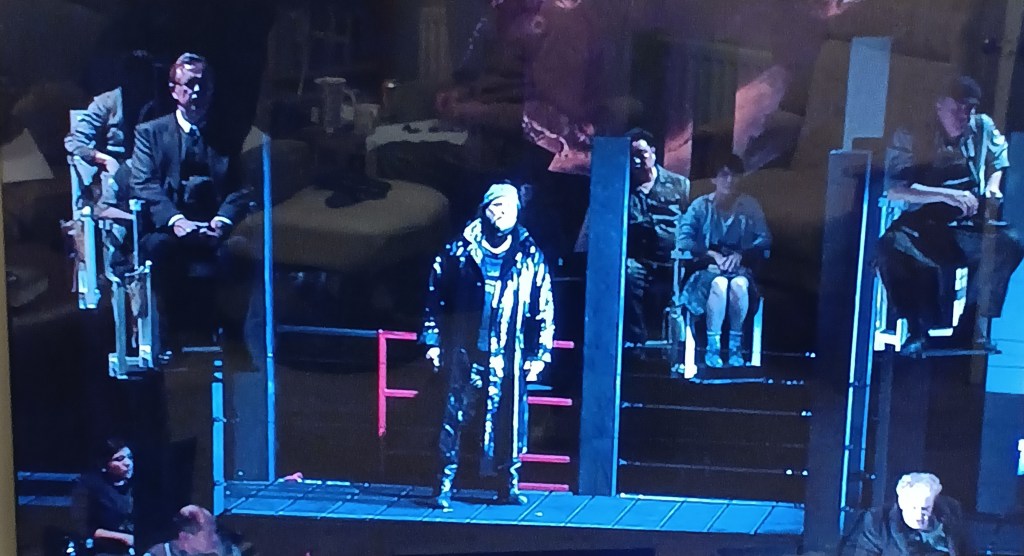

This is certainly the view of those who see him as vulnerable and a ‘victim’, the common stereotype of the misunderstood and oppressed ‘homosexual’ in the 1950s, at least for those who had empathy for outcasts. My own reading of the latter arioso (a heightened recitative but short of an aria) pieces is that they illustrate hopeless attempts of some kind of loner forced to understand themselves without a model that might interpret them to themselves or others. Only such models can help loners to find their appropriate level and role in a community they can not respect. They can not respect it because hoi polloi see the world as without complications, whilst they see the complications without understanding or being able to read them. This is more the feel in the version I did see (on DVD), David Pountney’s production for the Opernhaus Zurich with Christopher Ventris as Grimes.Here Grimes stands alone and aloof raised above the mass of people at the Boar Inn on the stage, who ae stilled in awe or fear, and distinct from the raised individuals each at their work in their own cells of activity, mainly alone in their homes or workshops. He wears still his sealskin protective coat from fishing and woolen hat, singing as it were to himself. The final stanza of course finds a change in the music where the bewilderment, implied by the sight of an imagined herring shoal, Grimes feels is both in the music and, in this production, acted out as Grimes falls into a kind of frenzy.

‘Mad or drunk’, the inn guests say to cheer themselves up for not quite getting this strange man, as they return to their pleasures with beer or the ‘nieces’. The Methodist Robert Boles, drunk though a Methodist and clearly not for the first time, interprets all this oddness in terms of Grimes reputation with workhouse boys: ‘His exercise / Is not with men but killing boys’, and is only restrained from violence to Grimes by Balstrode. Balstrode then changes the tone by getting everyone to forget Grimes is there by for ‘peace sake’ getting someone to ‘start a song’. Grimes interprets that song (‘Old Joe has gone fishing‘), however with his own version of it, about suicide at sea.

For me the issue is essentially about a loner who does not know how to be other than restlessly at some not-necessarily-productive task, physical or mental (the kind of ‘busy-ness’ that gets clumsy pre-teenage workhouse boys killed, but not I think by Peter’s design) which he hopes to fulfill his quest for a ‘safe harbour’ or ‘home’, but finding none:

What is home? Calm as deep water.

Where's my home? Deep in calm water. (Act 2 Scene 2)

I think Peter Brett’s final conclusion about this opera is correct. Britten self-consciously made sure that he turned the opera into, as Britten said in an interview, “a presentation of a general human right – that of the outsider at odds (for whatever reason) with those around him“. In my view there is a mode of truth here that lies beyond identity politics and would be a better foundation for a new personal politics, that makes the inside of insides and outsides, divisions between ‘us’ and ‘them’ a thing of scrutiny. for once scrutinised these denials of human rights whether from Mrs (Nabob) Sedley (in the opera), Benjamin Netanyahu or J.K. Rowling just show in their full ugliness. Mrs Sedley looks for crime everywhere, and finds it – but only pins it to those who fall below the security of common acceptance or the kind of alienation and anomie common in cities:

Crime - that's my hobby - is

By cities hoarded. (Act 2 Scene 1)

My ignorance of music, much, much more than E.M. Forster and Edmund Wilson, who still call themselves amateurs in their essays reprinted in the Cambridge Companion to Peter Grimes edited by Brett (pictured in my first collage), means I can’t comment on the workings of the music, although there are brilliant attempts to do this in the Brett volume by Hans Keller, David Matthews, and Brett himself . They you have an ability to read musical scores to be appreciated however. Nevertheless they have made me alert to the manner in which the music and lyrics do not always in opera tell the same tale. I will try and keep alert to this in March.

But do we need a queer reading? I think not, for we just have to sit there as our queer selves to get that, for we will recognise ourselves in the play’s cognitive music, but not necessarily in that disappointing thing they call’positive images’.

That’s all for now

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx