‘without transformation / Men become wolves on any slight occasion’. This blog takes as its starting point, Jacob Kerr (2025) The Wolf of Whindale, London.

Is it conceivable that, asked to choose an animal you like, you would choose one you consider yourself to be like. There is no certain link or even line of development forwards or backwards from the verb ‘to like’ and the adjective ‘like’ indicating similarity, although etymonline.com posits a possible development from adjective to verb. That explanation is italicised and bolded by me below:

like (adjective) “having the same characteristics or qualities” (as another), c. 1200, lik, shortening of y-lik, from Old English gelic “like, similar,” from Proto-Germanic *(ga)leika- “having the same form,” literally “with a corresponding body” (source also of Old Saxon gilik, Dutch gelijk, German gleich, Gothic galeiks “equally, like”). / This is a compound of *ga- “with, together” + the Germanic root *lik- “body, form; like, same” (source also of Old English lic “body, corpse;” see lich). Etymologically analogous to Latin conform. The modern form (rather than *lich) may be from a northern descendant of the Old English word’s Norse cognate, glikr. / Formerly with comparative liker and superlative likest (still in use 17c.). The preposition (c. 1200) and the adverb (c. 1300) both are from the adjective. As a conjunction, first attested early 16c., short for like as, like unto. Colloquial like to “almost, nearly” (“I like to died laughing”) is 17c., short for was like to/had like to “come near to, was likely.” To feel like “want to, be in the mood for” is 1863, originally American English. Proverbial pattern as in like father, like son is recorded from 1540s.

like (verb) Old English lician “to please, be pleasing, be sufficient,” from Proto-Germanic *likjan (source also of Old Norse lika, Old Saxon likon, Old Frisian likia, Dutch lijken “to suit,” Old High German lihhen, Gothic leikan “to please”), from *lik- “body, form; like, same.” / The sense development is unclear; perhaps “to be like” (see like (adj.)), thus, “to be suitable.” Like (and dislike) originally were impersonal and the liking flowed the other way: “The music likes you not” [“The Two Gentlemen of Verona”]. The modern flow began to appear late 14c. (compare please). Related: Liked; liking.

like (noun) “a similar thing” (to another), late Old English, from like (adj.). From c. 1300 as “an equal, a match.” The like “something similar” is from 1550s; the likes of is from 1630s.

I take Jacob Kerr’s new novel The Wolf of Whindale as a means of developing this idea for this is a book obsessed by the fearful dislike and obscure likings of animals, even their imitation, and identification in forms that themselves cross boundaries of substance type – bulls made of minerals and the stuff of cognitive affective legends, and wolves that may be human or turn into the like or vice-versa, or canine sub-species that pass as each other (dogs / wolves) and who also are in various ways human as well as the stuff of myth, especially Mithraic cult myths or Mithraism (once especially prominent in the borders of Roman Britain) in which bulls predominate and wolves overlook and stone minerals are the source of the birth of gods, monsters and heroes – in the latter case of Mithras itself). However, my identification of my favourite novel will be a sideline theme in this blog.

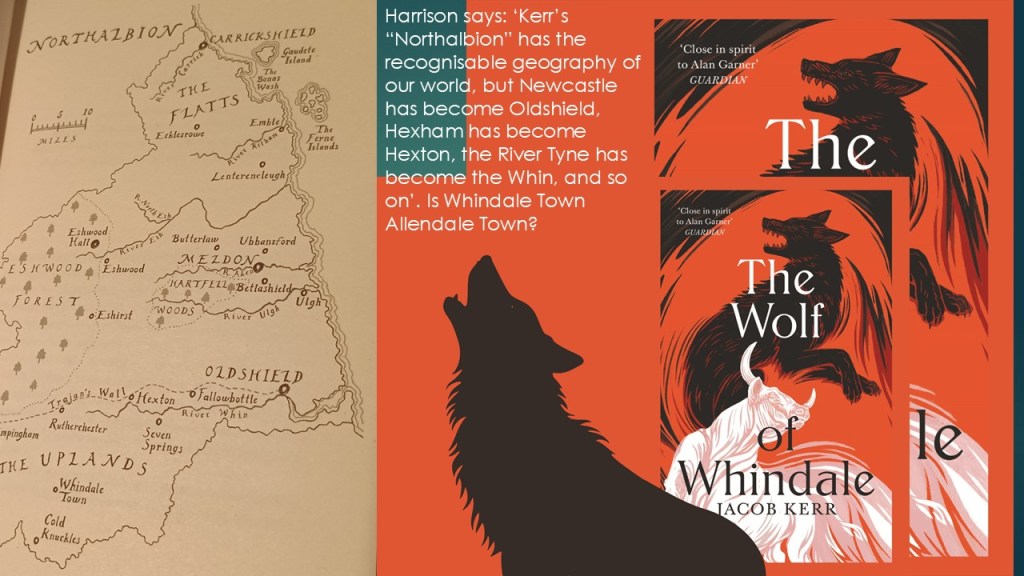

Niall Harrison in his Focus Online reviews of science and cult fiction makes the point well in perhaps the best description of the book I have found, when he says gnomically “Kerr has wilder plans”, for his novel’s development. [1] He infers, if he does not develop for that isn’t his purpose, that, as well as plotting the history of lead-mining in Northumberland (North Albion in the book’s own map of the novel’s fictive ground) from Allendale to Hadrian’s Wall (which becomes Trajan’s Wall in the novel) and the transformation of the region’s economy to coal, iron and armaments.

Even the main shift in time and space in the novel, from the Whinbush to the mine at the Sill, near Trajan’s Wall, can be read historically. Harrison differs from me on this. He says of the story after the shift, this:

The chapter set in the Sill is a tour-de-force of unfolding strangeness. The workers appear deployed haphazardly, like “a schoolroom full of scapgrace rattlescawps made to stand facing the wall”; the wrongness, Caleb realises, is that they are working alone, not in the tight partnerships he is familiar with. He can’t identify the rock, laced with “a strange yellow oxide like whin-flowers.” The work itself proceeds in something like a trance. … [1]

Unlike Harrison, I see those men at the Sill, not as merely fantasy elements where men become ‘automata’ or even in the chase after the obscure missing factor in their labours, ‘the knack’ craftsmen once had, zombies but as a symbol of the object of the alienated labour that became the lot of the working class in the nineteenth century.

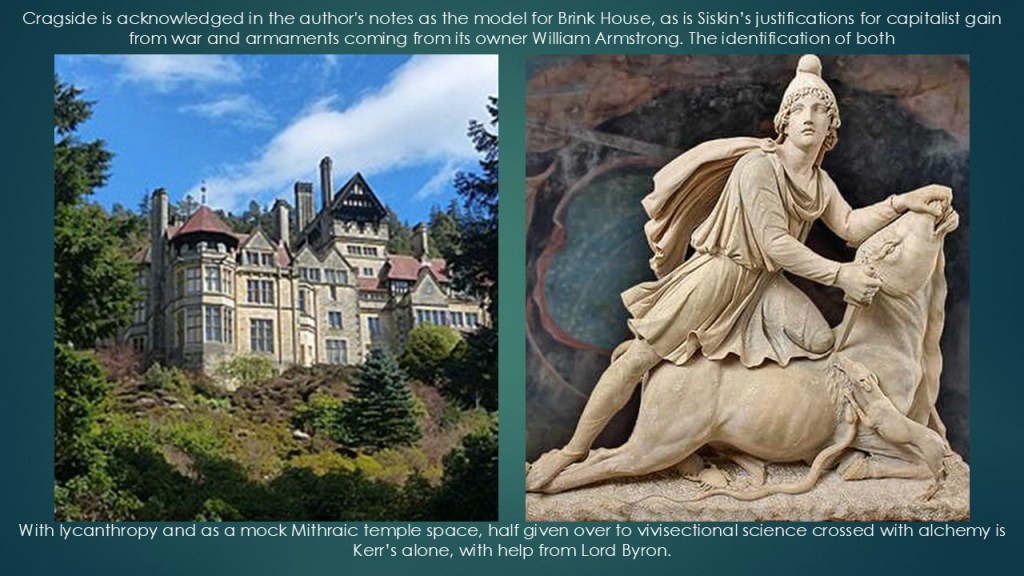

Within this larger historical transition (in which an avatar named Siskin of the great capitalist entrepreneur, William Armstrong (1810-1900) and his house at Cragside (becoming Brink House in this novel) plays a large part. Deep in the novel’s structure, and appearing earlier when it is unclear how central a character Siskin will become, is a side-glance at of the history of ‘combinations’ in labour history, their outlawing by Governments and aping by capitalist leaders, like Armstrong.

Combination was the original name for the nascent trades unions that was used against them in the and the ethics of combination or otherwise play a part in the plot, which though opening in 1845 recalls the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800. In fact by 1845 the term trades unions was more common (legalised in 1824) but the forces of social repression were no less. The novel focuses in on the reflection of oppression against the unions and resistance in the history of the strategy of repression in which working-class people became paradoxically the victims even of the need to protect the right of working people to form unions or ‘combination – in the social drama of the use of ‘blackleg’ or ‘scab’ labour in industrial areas and the violence that fostered. But as we shall see Kerr uses the becoming archaic term ‘combinations’ for a reason for the processes of combination and assembling of disparate things is very much his theme.

And this is why Harrison shows that the novel seems, as it turns more and more into a fantasy where historical time and space (underground , overground, interior and exterior) become flexible and unconscious in their passing) turns into the thing it is – a vehicle for arcane knowledge of what Harrison calls ‘an ancient sect’, that of Mithras. Brink House becomes a kind of Victorian mock-Gothic (Cragside is mainly mock Tudor) space whose walls and interiors become facades, or ‘masking’ for secrets both scientific, alchemical-magical and ritual hidden often behind its apparent walls or its cellars, in which a carnal storage house of a werewolf’s victims is encrypted.

But the meaning of all these mask disciplines is actually an art as much that of a novelist – the art of ‘combination’ and ‘separation’ (even syncretism in the development of religions, by which novels for instance model relations of group community and character individuation and the processes of change and transformation over both space and time. [2]

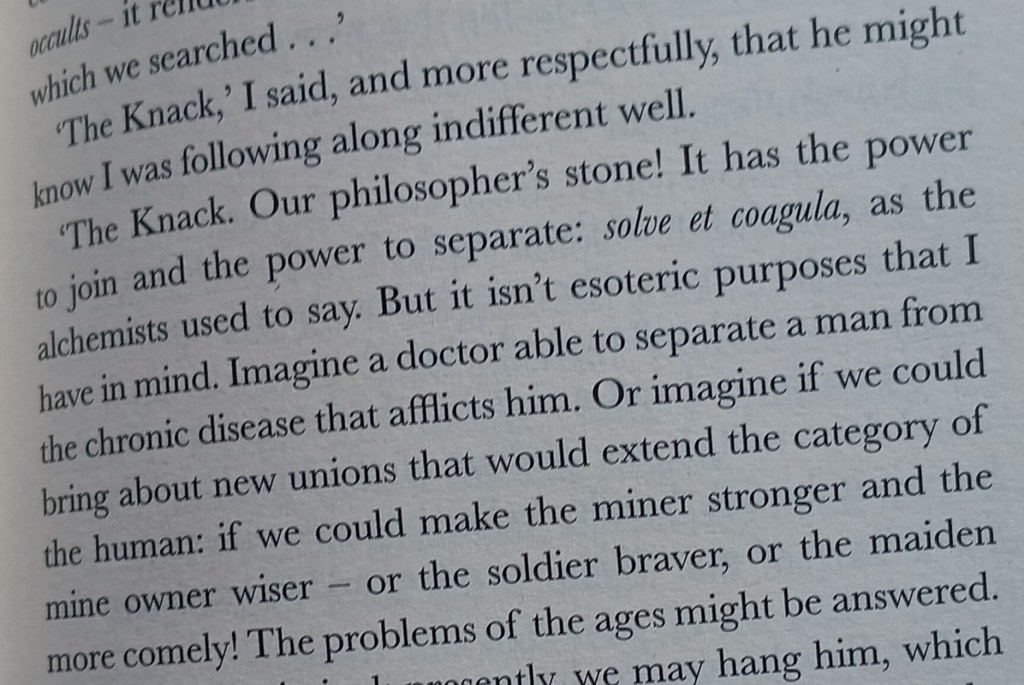

And transformation, combination, separation, historical and personal change and stasis are the heart of this novel – its central knowledge being the acquisition of the artist’s ‘hand’ for making, crafting and writing, a thing it calls ‘The Knack’, oft a name for the practical knowledge and skill that enables things to get done, but it is not automatically acquired by simple means. In Brink House and Siskin’s Sill mine the Knack is central as it is to the narrative and is desired by any individual who wants things to change, not least the loup-garou, Siskin, but which does not encourage, at least for working people, combinations between workers that challenge individualism.

Jacob Kerr (2025: 159) ‘The Wolf of Whindale’, London, Serpent’s Tail.

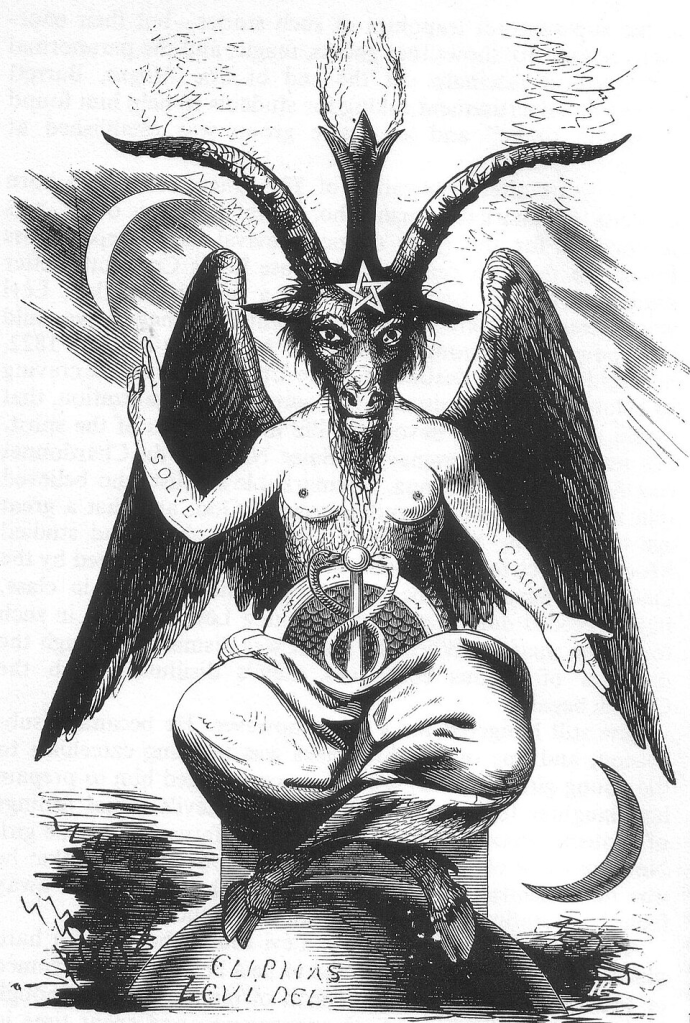

The phrase solve et coagula has a long history in Hermetic philosophy and magical practice, most centrally in alchemy, of which Siskin is thought of as an adherent and practitioner.It is throughout an especially in the work of Éliphas Lévi, has not only a practical but political and socialist aim for Lévi, who represented it iconographically in the form of a hermaphroditic human-goat (see below), if not for Armstrong as an explanation of the change of substance into higher more spiritually developed forms (see the entry on Baphomet in Wikipedia for more). But however wrapped up in the dressing of Mithraism and alchemy, the Knack is wanted Siskin explains to solve the ‘problems of the age’ in medicine and warfare.

An 1856 depiction of the Sabbatic Goat from Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie by Éliphas Lévi.The arms bear the Latin words SOLVE (dissolve) and COAGULA (coagulate), reflecting the spiritual alchemy of Lévi’s work.

But we know too that he wants it as a means of processing change and transformation in himself – from older age to youth (specifically the youth of Thomas Plover / Playfair (the latter is the narrator’s allegoric name for the man), the son of a union leader Siskin killed whilst transformed into his wolf self, from perhaps the cycle of his lycanthropic bondage to stable and more solidly human genetics, whilst still possessing his own self-seeking mind and ambitions. The man who transforms as a matter of mythically prescribed cycles of the moon desires to achieve self-directed change as a man who might then guide nations in his own interest as a capitalist. Kerr takes this, as he shows by the using the second stanza below as an epigram to his novel, from Lord Byron’s Don Juan, an attack on the merciless immorality of his age represented by men, who do not need to be wolves to be cruel and merciless but are this anyway, becoming ‘wolves on any occasion’:

.... We have

Souls to save, since Eve's slip and Adam's fall,

Which tumbled all mankind into the grave,

Besides fish, beasts, and birds. 'The sparrow's fall

Is special providence,' though how it gave

Offence, we know not; probably it perch'd

Upon the tree which Eve so fondly search'd.

O, ye immortal gods! what is theogony?

O, thou too, mortal man! what is philanthropy?

O, world! which was and is, what is cosmogony?

Some people have accused me of misanthropy;

And yet I know no more than the mahogany

That forms this desk, of what they mean; lykanthropy

I comprehend, for without transformation

Men become wolves on any slight occasion.

Gordon Lord Byron Don Juan, Canto IX Available at: https://www.poetryverse.com/lord-byron-poems/don-juan-canto-the-ninth

Byron uses wolves here as a hidden simile. Modern men become like wolves rather than transforming into them as in ancient ritual. As Byron suggests ‘mortal man’ knows little of ‘philanthropy’, preferring ‘lykanthropy’ (sic.) and in this is essentially ‘like a wolf’, in as far as we have a stereotype of wolfish behaviour. The point is that the process of transformation of humanity to something considered less than human is not a matter of magical transformation but of other processes attached to change, not least the self;f-interest of the few becoming in Byron’s time the lever of change and acquisition of power and wealth. Compared to this wolves are more like the dogs, the species became in becoming domesticated.

Kerr cleverly shows this in the dual forms of Absalom, a wolf, who many in the story take as being a charming if large dog, who (in a reverse cycle from the traditional werewolf Siskin) turns into a human man, eventually taking on the name Adam to be so, under the guidance and foster-parentage of a woman who is called in the novel, a name that looks like La Ghoul and who serves Siskin, but turns out to be a woman in rebellion against him. The stanza of Byron’s proceeding that used as epigram by Kerr was clearly in Kerr’s mind. Byron, perhaps cynically since he points out that the sparrow feels the consequences of the Fall whilst, unlike Eve and Adam doing nothing against God’s will,, puts the Fall of Man to Evil in Judaeo-Christian thought into the context of modern self-interest and the capitalist ethic. When Adam is born out of the dog-wolf-man, he takes a new Eve (though she renames herself Safia Saifi, the conjoined names of both male and female purity in Muslim cultures). The passage where Adam and She leave he presence of Caleb, the narrator, is an undoubtedly purposeful parody of the end of Paradise Lost by Milton, show in Adam and Eve leaving the Garden of Eden, a new beginning – with even a suggestion of conjoining in marriage in the ‘bridleway’ they head towards, a ‘mystery’ Caleb refers to because here human and animal would be a feature in their future. Compare, for instance, these three sentences (with sections bolded by me) with the verse below it especially:

And so they went on their way together, Safia Saifi and Adam. I watched them go, the last of the morning mist, creeping daintily about their feet as they walked out across the gravel towards the bridleway, with no possessions and all the world before them. Where they would settle, and what the nature of their their accommodations were or would be, was for themselves to decided. … [3]

The World was all before them, where to choose

Thir place of rest, and Providence thir guide:

They hand in hand with wandring steps and slow,

Through Eden took thir solitarie way.

John Milton Paradise Lost Book XII Available: https://milton.host.dartmouth.edu/reading_room/pl/book_12/text.shtml

That felicity of the writing though is merely an illustration of the fact that this novel is about processes of change – in which principles of imposed and voluntary exclusion (separation) and combination or conjoining together play a part, and which make this novel rather ambitious behind its accessible fantasy facade, and where the alchemical formula (combine and then separate – solve et coagula -about the dissolution and re-coagulation of matter in newer forms) are actually taken quite seriously as themes in the novel, and will, nevertheless tells us something about my favourite animal – which is a dog by the way if you haven’t guessed yet. Let’s think first though about what is meant in a range of ways by transformation, change, ‘shift’, and on one occasion, ‘transfusion’, where what is transfused is the content of mind. In rural areas in the early shift to the needs of an urban society, the hills themselves will show the change from mineral resources given prominence in earlier days (like lead) to coal, iron and steel. Change happens through agents like Siskin but also new technologies and ‘knacks’, innovative ways of doing things> in the sill mine, asked what finding the Knack will ‘feel’, the best answer given is ‘conversion’, in a novel where ‘conversion is as like to refer to conversion through tenets of religion, or even magic.[4]

Changes in socio-cultural forms like religion and belief happen in a more obvious piecemeal way wherein facets of differing religions combine and separate once in new form, which the Romans fashioned by adopting and transfusing Gods like Mithras into being part of their pantheon. Likewise it refers to ‘those who wanted to immix the various dissenting sects of Christianity into a single brotherhood of crackbrains’, as Caleb analyses nineteenth century Dissenting Church history. All of this is change by separation, recombination and then separation into a new entity, even if we call that change ‘syncretism’ by adopting foreign Gods as we conquer territory: “They absorbed them, folding them into their own beliefs, which were capacious and ever proliferating’. But all this is the case is that change creates meetings of the old and new at edges or boundaries which are yet indistinct and liminal. This novel is full of edges, brinks and sills. Siskin says that ‘the best things in life are to be found at its edges. … Trajan’s Wall was certainly an edge: the northernmost reach of the Roman Empire …’. [5] It is also not unlike the transformations of kind and quality that happen when pigeons become pigeon-pie and then get absorbed by eating Caleb thinks as he eats La Ghoul’s fine French cuisine: ‘… here on the margins of a decrepit empire, the process of syncretism was churning away, with all the devouring and the digesting and the synthesising and the excreting that this entailed’. [6]

The traditional and the inverted werewolf both name their changes ‘shifts’. [7] Siskin’s shift however into the body of Young Tom, described hilariously by Caleb as the process of having ‘slid himself over into young Tom here’ has the grandiose name, as aided by The knack, of ‘Mithraic transfusion’, explained further to Tom by Caleb as ‘a kind of induced metempsychosis. I think he was going to use it to shift his personality into a new vessel’. Yet again its all about combination and separation in different configurations. Those ex/changes take place sealed ‘with a handshake’. [8] And we have to remember that the Knack takes form as a ‘hand’, just as Mithiraic cults were associated with the Roman social practice of male hand-shakes: ‘Worshippers of Mithras had a complex system of seven grades of initiation and communal ritual meals. Initiates called themselves syndexioi, those “united by the handshake”. [9} Through the hand that the Knack becomes on Caleb (because he unadvisedly touches and fuses with it in the Sill mine) he eventually becomes an artist, who certainly do need the ‘knack’, but hands throughout are linked to their changeability – from the grossest (with a chisel as operating tool) to the most refined surgery in Siskin’s laboratory to the development of skill from practice. The texts of a fictional history of Northalbion Mithraism scattered through the novel the best gift of Mithras to initiates is described first as Dei manus, a rather inverted term for the icon of God’s intervention in the world’s history in Christian Art. The fictional text however continues to describe other transformations in the name of this phenomenon, for in this novel change of name is an important feature.

The nomenclature subsequently changed, however, either by textual corruption or intentional substitution, to the rather more secular Donum manus: ‘given hand’. In the last of the surviving Latin texts, this has changed again to daemonium manus: ‘demon’s hand’. In English, it came to be known as the Knack. [10]

Caleb should have known this because as he touches the Knack in the Sill mine wall with hi own ‘maimed’ hand (destroyed by a gang of union members and then a vulpine doctor), a process he eventually describes as a blood transfusion: [11]

Becoming ruled by the hand as if it were an externally motivated thing is a horror trope, but I find it brilliantly ‘handled’ (so to speak) in this novel, as the hand starts as an ‘it’ and a thing’, only under the cover of a bandage slowly combining with him and eventually becoming him, in a final act of separation of from its origin. It is an account of personal change – from young to old man, miner to artist, ‘invalid’ (as scabs are too socially in mining communities) to someone validated and whole. And this is the case with history in the novel too. It works in describing personal as well as social change histories through a writer’s word magic – notice how human and animal transfuse in the word ‘birdlike’ to describe the ‘maimed’ hand, as the man’s sense of self-alienation involved in combination with something ‘other’ than his past known and accustomed self is brilliantly evoked.

And the writing works, shows the writer’s ‘knack’ and ease of ‘hand’ even in micro-transformations in the text, and it is in this respect that I chose to write this review as a response to a ‘favourite animal’ prompt. At one point when La Ghoul tells the story of the terrible birth of the ‘litter’ (the prose expresses surprise at this because we know it was a ‘litter’ of liminal human-animals) of which Absalom was one ‘pup’ or ‘cub’, Caleb has thoughts about what Absalom, who is present for the story, thinks of all this:

I looked at Absalom, where he lay upon the dark oak floor, chin resting on his paws, and tried to guess at whether he understood what was being said. You never know with dogs.[12]

Isn’t that brilliant? After all the prose makes certain naming assumptions, it names the creature a ‘dog’, even though we know it is a ‘wolf’ and not a simple wolf but one that becomes human by virtue of monthly cycles of the moon. Even using the word ‘chin’ is beautifil for both dogs and humans have chins but humans do not have ‘paws’. The fact is here is the potential; of a dog, who is a wolf, or a wolf who is like a dog, whose capacity for being human too is queried, all around the issue of ‘likeness’ as language plays with it in naming and describing its subjects. My favourite animal is a dog, because all those questions emerge in any human – dog interaction. Try another example: [13]

This is very playful prose following a comic drama in which Caleb is continually reassured by La Ghoul that the animal that accompanies her is a dog, not the wolf that pursued him at Whindale Town earlier in the novel. Yet the games the passage p;lays can be only appreciated by dog lovers. ‘loping along at terrible speed, suggests, even before we see what the object of the sentence really is, a WOLF – and Caleb has felt haunted by wolves for some time. Yet dogs do lope – it is just not the association here, witness my Baz loping:

Only the presence of the ball and a presence in the eyes(and the pink harness) in this photograph suggest that this is not hunting behaviour, for it is derived from such. Caleb, having been hunted by a wolf, uses the words here to reassure himself that a ‘hunting’ him may really, on second look be a dog ‘exercising’ and ‘playing’. Nevertheless the feeling of watching the dog, though reassuring his need for security, still has him by the throat, as a wolf does, at least in human imagination. This is why dogs are favoured by me, I think. And, after all, wolves have become dogs, which on occasion become wolves again.

In the above examples however, my real purpose is to demonstrate the incredible knack in the hand of a writer of good prose – a facility of ‘given hand’ too. And this is not just in writing the micro-events of the novel with all kinds of transformation of mood in them but in plotting the novel as well, including pacing the novel between moments of descriptive power and faster narrative pace that keeps readers gripped. I thought of this reading Niall Harrison, before mentioned, gives of the opening moves of the plot, noticing that these become part of the machinery of combination of events which generate the novels main theme:

Two events combine to get the narrative moving. First, one of the workers, a union organiser, is found gruesomely dead, head ripped from torso, in a killing that is generally attributed to the titular wolf; and second, a new mine-owner by the name of Siskin is seeking to force the workers from flexible to fixed-hours shifts, which you might suspect gives him motive to do away with a union organiser. …

Notice how novelists, too, organise plot around combination and separation elements. Only at first is the combination of events in the storytelling merely a conjunction of contingencies. Moreover, the scab subplot is a moment of separation that will bring Siskin and Caleb together. Caleb, in truth, tells us that the scab subplot is a moment of narrative ‘shift’. Again Harrison picks out Caleb’s statement at the time in which he calls his ‘contrarian’ (his word) decision: “a fearful moment for me, caught as I was betwixt my old life, in which I was as one defunct and exanimate, and a new life into which I was yet to be born”.

Likewise, Harrison notices how the wolf plot emerges first of all as a kind of red herring, thus enriching the plot’s actual development:

The town priest likens Caleb to a wolf among the flock, and for a few pages it seems that might be it for the title. It seems as though the alternate world may be the only fantastic element in the book.

At one point, the novel asserts that the real effect of the Knack is to find the ‘signature’ of the Maker of the world in things. Isn’t that Kerr’s signature as a rather good writer. But no more! This has been too enjoyable a piece to write for me not to admit that it has produced a messy blog. However, it says what I want to say about this rather good book, and fits in why my favourite animal is a dog, as if it were relevant to the blogs wider aims, I think!!!! So here it goes online.

Bye for now

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

_____________________________________________

[1] Niall Harrison (2025) ‘The Wolf of Whindale by Jacob Kerr: Review’ in Locus Online available at: https://locusmag.com/review/the-wolf-of-whindale-by-jacob-kerr-review-by-niall-harrison/

[2]] For syncretism as combination and separation and the theory of ‘edges’ see Jacob Kerr (2025: 156) ‘The Wolf of Whindale’, London, Serpent’s Tail.

[3] ibid.: 298

[4] ibid: 116

[5] ibid: 156

[6] ibid: 157

[7] ibid: Chapter 13, 243ff.

[8] ibid: 265, 264 respectively.

[9] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mithraism

[10] Jacob Kerr op.cit.: 239

[11] ibid: 123

[12] ibid: 203f.

[13] ibid: 164f.