Our ideas of what might be sold at a cost that allows for profit to its investors, rather than just payment for the technicians that discover and refine it from sources, has been deeply influenced by water.

Consider this blog post (full post linked here) which posits that some people already pay to breathe air, although what they pay more be more considered the equipment that enables the capacity to breathe air than the air itself.

Breathe in…breathe out…breathe in…breathe out and repeat. Every second, of every minute, of every day, of every week, of every month, of every year, for the rest of your life. It’s a simple concept, and most of us take it for granted, a continuous cycle, and something that runs parallel to our everyday existence. It’s essential to life, which means we can not survive without it, we would simply die. The air we breathe is freely available all around us, our bodies consume this resource repetitively with every breath we take. Every single human being has the basic human right and need to breathe, and it costs nothing, after all the air we breathe is free. Or is it?

To illustrate the sale of air by this instance then is a logical mistake perhaps: best illustrated in the last two sentences of the paragraph above: ‘Every single human being has the basic human right and need to breathe, and it costs nothing, after all the air we breathe is free. Or is it?‘ We are not after all, in this instance querying whether ‘the air we breathe is free’ but whether the supposedly natural act governing access by human beings of air – the mechanics of breathing is ‘free’. After the paragraph, the next sentence makes this clear:

For people who live with ventilation, breathing is not something that comes naturally and not something that comes for free.

In order to ask whether air id ‘free’, we need to look at other instances where what is for sale is not apparatus to enable or aid breathing, which clearly is a commodity, produced, retailed and consumed by some anong all human beings, but the ‘air’ itself’ – the invisible mix of necessary and other gases. There is already a market for refined air, called ‘fresh air’ to emotionally link to idioms in English about the ‘value’ of ‘fresh air’ in particular. Such air, sourced supposedly from remote locations relatively less effected by pollution or other breathers (breathers- out of oxygen- depleted air) is already for sale.

During Covid lock-downs the company ‘My Baggage’ , marketed air collected in different locales in the UK, although for people forced not to travel to those locales during that period, it is a moot point whether what was sold was mentally valued associations of those locales to those unable to access them directly.

But this is the case with mountain-bottled air too.

Some socialist analyses point out that it is not necessary to ‘bottle’ or ‘can’ a product to commodify it indirectly, since it can be sold as an adjunct to housing or location or tourism (the British Raj ‘summered’ in the Northern mountains of India (before they partitioned it) to access ‘fresh air’. Even as far back as 1848, Freidrich Engels showed that ‘fresh air’ was monopolized by the bourgeoisie of Manchester, as this old 2022 article from Socialist Worker argues, correctly I think, and make the connection to bottled air:

In The Condition of the Working Class in England, Frederick Engels described how the rising capitalist class—the bourgeoisie—protected itself from the smog of its industries. He writes that they “live in remoter villas” or “on the breezy heights of Cheetham Hill, Broughton, and Pendelton, in free, wholesome country air”.

In other cities—such as Leeds—the rich made sure to build their areas high up, away from the prevailing winds that brought pollution from their factories. Today some of the world’s super-rich are even buying bottled air from the Swiss alps.

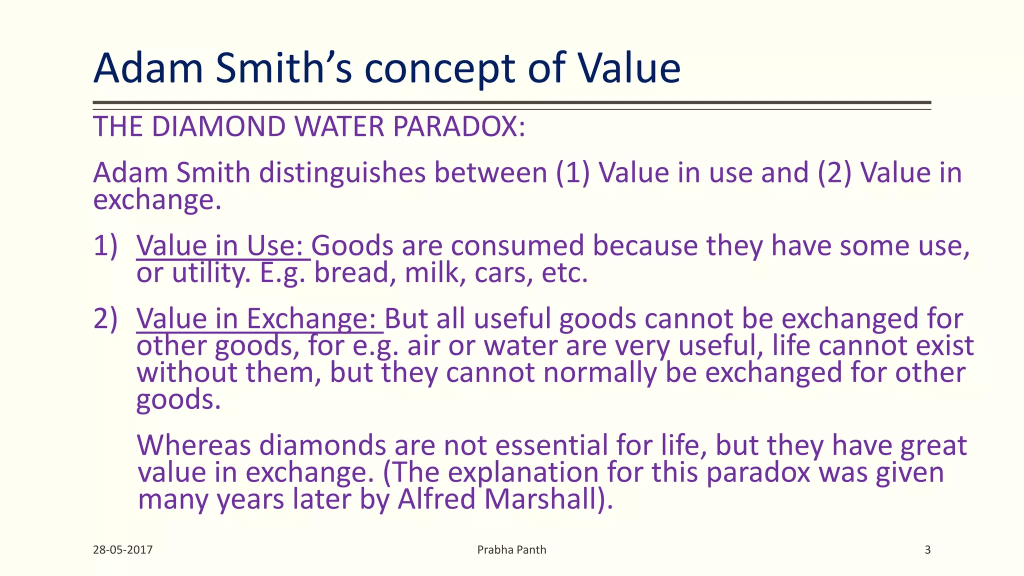

So it turns out the ‘crazy business idea’ of selling what is supposedly ‘free’ is not a goer for me, were I tempted – it is happening already. And we should have known that because supposedly free ‘common goods’ (as land once was) have been almost entirely now costed to ensure profit for a few. The supposed ‘father of modern capitalism’ in the eighteenth century tried to explain why water is free – not valued in exchange value terms, while less plentiful and less necessary ‘goods’ were:

Some write ups of the concept of this eighteenth century moral philosopher [see this blog on the James Graham play Make It Happen, which featured Smith, at this year’s Edinburgh International Festival] fail to emphasis the paradoxical in this distinction – that something of far more use value (indeed to necessity) in this comparison has less exchange (or monetary) value than a useless thing like a diamond.

The latter kinds of account stress the issue of either labour-value (but I won’t argue the case) or the oire fetishised notion in classical economics of scarcity, which is in fact a portmanteau for a number of economic factors. See this example, whose source I can no longer find:

In 1776, Adam Smith introduced the ‘diamond-water paradox’. It stated that although water constitutes a basic element for survival and well-being, it holds a lower price in the market than diamonds, which have a greater scarcity value. The assumption that water resources were unlimited thrived amongst social scientists for centuries.

More recently, though, societies around the globe face a crisis in the management of water resources due to population increase, river pollution, climate change, inefficient/wasteful irrigation, and water mismanagement. The supply of fresh, clean water is now recognised to be finite. Efficient water supply is sure to emerge as an urgent 21st century resource issue. Will the scarcity of water increase its value?

This advertisement material attempts to annul the diamond-water p[aradox. How? By virtue of fetishisation of the commodity?

I can use this, however, to shift my focus from air, whose privatisation is in its infancy, to water, whose privatisation has a long and tragic history unfortunately, for those who value clean and pure water, as we all must if we but knew it and, as a consequence, voted for it – which would mean currently voting Green.

But remember that the quotation above uses the word ‘value’ as if there were not a paradox in the idea of ‘value’ and valuation, which of course there indubitably is.

So much for my crazy business idea? I suddenly remembered its basis is explotation. Don’t you all love exploitation. You vote as if you do!

With love

Steven xxxxxxx