The fever of seeking recognition is at least one of the characteristics in the origin of the social, or aristocratic, vampire in literary myth. We could all do fame-seeking! A case study based on John William Polidori’s life and writing, [OR], ‘He watched him; and the very impossibility of forming an idea of the character of a man entirely absorbed in himself, … , allowing his imagination to picture everything that flattered its propensity to extravagant ideas, he soon formed this object into the hero of a romance, and determined to observe the offspring of his fancy, rather than the person before him’.[1] That man, whether it be himself or some other hero, will so ‘haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights / That thou would wish thine own heart dry of blood / So in (his) veins red life might stream again’.[2] Our ambition for the legendary life of the immortal artist or hero is the origin of the Romantic revitalisation of the lore of the vampire / vampire! This is a reading of John Polidori’s story fuelled by the wonderful book by Andrew McConnell Stott (2014) The Poet and The Vampyre: The Curse of Byron and the Birth of Literature’s Greatest Monsters New York, Penguin Books LLC.

Great ambition is a fearful thing. It is so if it is in the form of an object we claim to love because of its felt transcendence, and seek a return, even a ‘diminishing return’ in the language of economics, of such Love. It is so too if it is an ambitious desire for our own future self-image, perhaps even an undying claim to immortality of fame, for literary ambition reaches thus far. In the early nineteenth century, where Stott’s well-researched story, based on factual evidence, is set there were clear examples of both – Napoleon, for instance as a type of the revolutionary leader, or a poet like Byron, or Scott (representing writers of the fancied left or right wing respectively). Shelley, who comes into the story in a major way, thought poets the ‘unacknowledged legislators of the world’, so for the Romantic era there was even a confluence between these two ambitions. By the time George Eliot wrote Middlemarch even a country doctor, Dr. Lydgate, could set his ambitions high, though his researches might fail as his ‘spots of commonness’ grow to fruition.

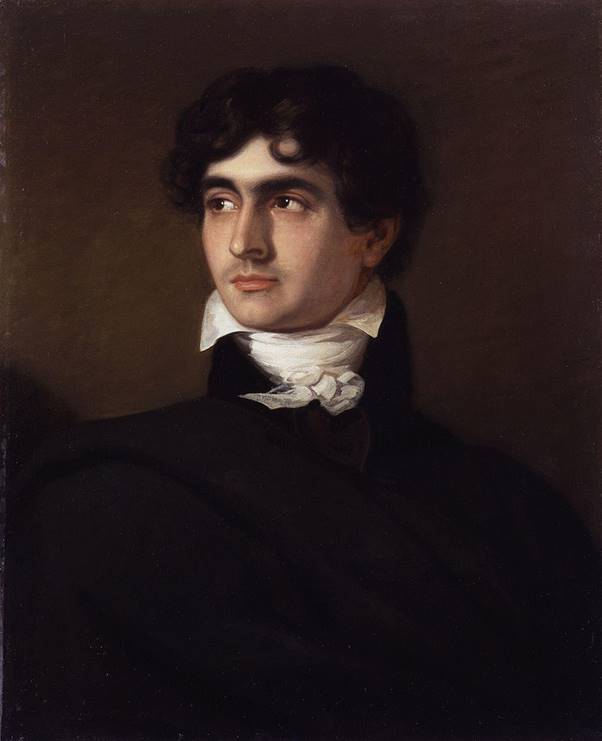

However, Dr. John William Polidori had no such ambition as a medical researcher, though it fascinated him to be appointed the doctor appointed to travel to attend the various unpredictable ailments in various body parts of George Gordon, Lord Byron – partly because he knew so many European living and dead languages. It fascinated him because Byron was a nobleman-poet and incredibly famous and infamous as a lover as well as writer (though less clearly, other than in infamy and suppressed smouldering truths, of young men), with an image that looked set to endure. Besides Polidori was a writer too, forced into medicine by his father Gaetano, but still working on a tragedy for the London theatre, works of philosophy, memoir, travel, poetry and fiction who long cherished greatness with some shade of equivalence to his employer, and hoped friend Byron.

People continually tried to warn Byron of dangers attending the appointment of J.W. Polidori, including John Cam Hobhouse, who became a life-long enemy and object of hatred for John, who Stott believes even warned Byron in code (a code I still can’t read) that the handsome black-haired youth was an:

“odd dog”, …, possibly suggesting that he suspected him of homosexuality, adding, “I don’t like his ori”.[3]

We pronounce ‘ori’ in the man’s name like ‘whore-y’ (perhaps that’s the code). Stories of Byron’s adventures and passions for young men are only blossoming in current research but were carefully suppressed then, and nowhere does Stott make a case for the elongated endurance of John Polidori’s oddness’s, and they were many, by Byron, despite repeated warnings about him from others – eventually including Shelley – as rooted in feelings for him and his attractive exterior. Yet John’s own identification of Lord Byron as type of the vampire, in the first ever appearance as a society gentleman vampire unlike the horrible creatures of Greek and Turkish folklore, clearly fed off the view of Byron as capable of anything but able to keep that fact buried (at least from the light of day).

Byron’s nearness to the type of what would become the society vampire was already established among society ladies – his public prey. Stott charts the fascination of Claire Clairemont with Byron as a reader of his poetry and of the picture of him in Lady Caroline Lamb’s semi-hidden picture of him, under the name Lord Ruthven in her novel Glenarvon. Wikipedia helps fill up the picture of Lamb well enough:

Lady Caroline Lamb (née Ponsonby; 13 November 1785 – 25 January 1828) was an Anglo-Irish aristocrat and novelist, best known for Glenarvon, a Gothic novel. In 1812, she had an affair with Lord Byron, whom she described as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know”. Her husband was the Honourable William Lamb, who after her death became 2nd Viscount Melbourne and British prime minister.

But Stott helps more because even before writing the novel he shows us that Lamb’s pursuit of Byron picked on his air of the supernatural, from the point of reading her advance copy of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. After meeting him in the flesh she said: ‘That beautiful pale face is my fate’. In the novel Ruthven (this is Stott’s citation) says to Calantha, again obviously the avatar of Lamb herself: ‘Unblessed myself, I can but give misery to all who approach me, …. My love is death”.[4] Beauty, pallor would be the mark of the death-bringing society vampire up to Bram Stoker’s Dracula and beyond. Stott shows that Lamb made no bones of Ruthven being Byron and of both being equated with the ’spirit of evil’, if not a vampire as such. Stott tells us Polidori read Glenarvon. Lord Ruthven is the name he gives to his monster in The Vampyre, even though he changed the name in manuscript marginalia of the first print edition (see the illustration of the page from Stott below) to ‘Strongmore’. The name remains Ruthven though in the extant editions because the book was never published in his own name and often attributed, (which must have hurt most) to Byron as a more commodifiable name by the publishers.

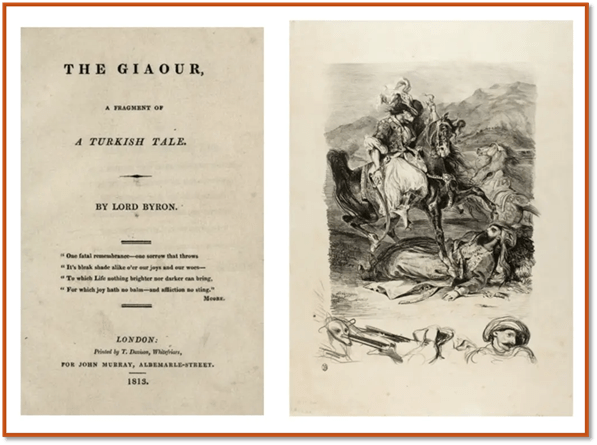

The Introduction to The Vampyre, not probably written by Polidori in the Edition published in the first Sherwood, Neely and Jones edition, which does not even name Polidori as the authour of The Vampyre, also contained a fictitious memoir by John Mitford pretending to be a true account of Lord Byron’s Residence in the Island of Mitylene.[5] This introduction cites Byron’s first use of vampirism in his The Giaour, possibly one of the most tedious of his many tedious jingling verse narratives, but this figure is not truly like Ruthven, for its victims are its own family and offspring:

But first on earth, as Vampyre sent,

Thy corse shall from its tomb be rent;

Then ghastly haunt the native place,

And suck the blood of all thy race;

There from thy daughter, sister, wife,

At midnight drain the stream of life;

Yet loathe the banquet which perforce

Must feed thy livid living corse, …1(cited)

Stott’s lesson about Polidori is actually bound up with obsessive sexual fascination and pursuit of Byron by Claire Clairemount, the half-sister of Mary Shelley (daughters of William Godwin), that lead to , for Byron, a few meaningless fucks, and for her a baby, Allegra (stolen also by Byron and who died in his neglectful charge). Whilst he never says Polidori has the same fascination, he draws the names together as dupes of Byron’ fame and / or allure sexually, which he ties together with the help of famous lines from Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto IV:

Love, fame, ambition, avarice—’tis the same,

Each idle— and all ill— and none the worst—

For all are meteors with a different name,

And Death the sable smoke where vanishes the flame.

Note ‘love’ is a disease like unto ‘avarice’ as well as to ‘ambition’. Think of this in this passage from Stott, where Polidori might be thought equally unable to distinguish his motivation towards Byron’s exemplum of Romantic fame, as he recounts that both Claire:

… and Polidori had sought proximity to it but, once within its beam, found that what they hoped would exalt them caused them only pain. Internalising the low-grade fever that was Romantic obsession with celebrity, its corrosive pathogens steered their course, moulding them into archetypes of grievance that would become increasingly familiar as the nineteenth-century drew on – …[6]

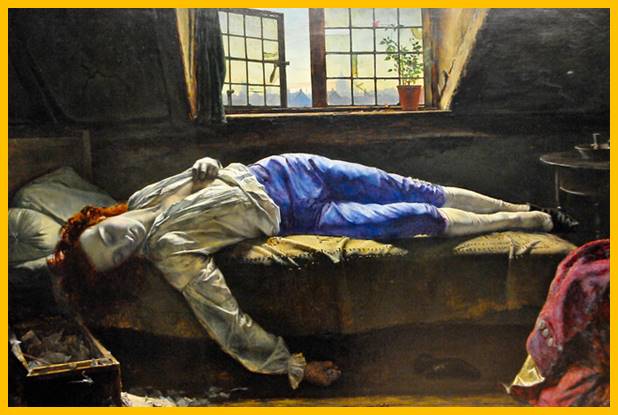

‘Ambition is the most assuming of all passions’, wrote Polidori, comparing it to a self-consuming furnace.[7] Stott cites it in full at the first of some fine pages that probably sum up ages of never-to-be-finished research I once did myself on the myth of celebrity, and better and more clearly than I would ever have done. These tie up the work of Isaac d’Israeli (the father of novelist and prime minister who created a less racialised name, Benjamin Disraeli) on exempla of the failure of writers to achieve even recognition that made them a living, because their standards, so the Romantics (and d’Israeli) felt, were trodden on by the march of commodity capitalism in publishing. The archetype of all was the eighteenth century Thomas Chatterton (I was drawn to the research by Browning’s fine essay on that poet after the Romantic swell of feeling about that boy’s fate – suicide in a garret – had died down). What I never discovered was that Polidori too, had like Coleridge and Shelley, set thought about Chatterton to verse, as well as modelled his own possible suicide on Chatterton’s. I haven’t found the verse itself, so refer to Stott’s description of Chatterton to His Sister (Chatterton had no sister).[8] Stott says that this poem about the fear of a ‘genius’ lost to posterity, namely Polidori himself,:

told of his hopes ‘mock’d by all the world’ and compares the flattery of men to the flapping of the ‘vampire bat’, its wings creating a lulling breeze even as its sucks its victim’s blood.[9]

That ‘vampire bat’ clearly also had the lulling waft in it of the voice of Lord Byron, although the holding may not be so romantically sexualised. The point about Byron was that it hid his sexual urges for young men, from boys that fascinated him at school that became the subject of poems disguised as about girls onwards to his final young Greek male lover on his death at Missolonghi. This theme of keeping one’s heart concealed is the very essence of Ruthven, who is characterised by holding the protagonist of The Vampyre, Aubrey, to an oath never to speak about his death after the murder of Ianthe, beloved by Aubrey, even despite the observed threat to the life of his sister that his broken silence might have deterred. Twice a voice whispers to Aubrey: “Remember your oath!”.1 This detail may have come from the story that Byron actually wrote in the story told by Shelley in the preface to his wife’s Frankenstein that birthed the monsters of Mary Shelley and Polidori (though Shelley never mentions Polidori – he was after all, strictly speaking, merely on Byron ‘staff’ and Shelley was suspicious of young bourgeois males on the make.) Byron’s unfinished fragment, Stott describes, as by an unnamed narrator telling of his travels with an older man called Augustus Darvell, who dies at a Turkish cemetery en route to Ephesus, and like Ruthven, who previously asked the narrator ‘to perform meticulous rituals after his death while not revealing his passing to any human being.[10]

Vampire’s need to keep themselves enclosed, especially their passions – their pallor being the product of blood that is no longer pumped by the heart to show passion in the face. Aubrey is fascinated, even before being bound to Ruthven by this trait in a man ‘’that few knew he ever addressed himself to females’, though he did. He hated laughter, especially female or ‘thoughtless’ laughter. I puzzle over this ambiguous passage:

Those who felt this sensation of awe, could not explain whence it arose: some attributed it to the dead grey eye, which, fixing upon the object’s face, did not seem to penetrate, and at one glance to pierce through to the inward workings of the heart; but fell upon the cheek with a leaden ray that weighed upon the skin it could not pass. His peculiarities caused him to be invited to every house; all wished to see him, and those who had been accustomed to violent excitement, and now felt the weight of ennui, were pleased at having something in their presence capable of engaging their attention. In spite of the deadly hue of his face, which never gained a warmer tint, either from the blush of modesty, or from the strong emotion of passion, though its form and outline were beautiful, many of the female hunters after notoriety attempted to win his attentions, and gain, at least, some marks of what they might term affection: …1

I puzzle because of that reference, by a doctor mind, to the ‘inward workings of the heart’, that both refers to its role in the circulation of blood, and as the engine of skin colouration, and closely linked emotional give-aways, even the ‘warmer tint’ of life. The passage refers to the action of his eye that did not ‘penetrate’ into the objects of his gaze, and stayed on the surface of the skin, ‘it could not pass’, like a dead weight. But it hovers too in the space between his own outward appearance and the eyes that ‘wished to see him’. Whatever their eye colour or quality of living, they too cannot pierce the heart of or get under the skin to their hope of warm flesh. Their ennui is the weight felt on seeing them not only on his cheeks but their own. But is it only the ladies that desire the attention that might single them out? Here is the passage I use in my title about Aubrey’s close observation of Ruthven:

He watched him; and the very impossibility of forming an idea of the character of a man entirely absorbed in himself, who gave few other signs of his observation of external objects, than the tacit assent to their existence, implied by the avoidance of their contact: allowing his imagination to picture everything that flattered its propensity to extravagant ideas, he soon formed this object into the hero of a romance, and determined to observe the offspring of his fancy, rather than the person before him.1

Again observing him is blocked by Ruthven’s ability to hide his interested observation of the observer, so that they might think themselves worthy of interested observation, the power perhaps of fame and celebrity, for all these are extravagant ideas, ‘meteors with a different name’. Remember Childe Harold:

Love, fame, ambition, avarice—’tis the same,

Each idle— and all ill— and none the worst—

For all are meteors with a different name,

And Death the sable smoke where vanishes the flame.

Aubrey cannot but think himself an ‘external object’ to Ruthven’s famed and desired gaze, which leads to his idealisation as ‘a hero of romance’. Is this hero one of a medieval romance – a knight of the Arthurian Court – or of more modern romances of sex and horror, like those of Monk Lewis, or even the trials of a modern love tryst. By romanticising Ruthven will he catch the eye of the ‘offspring of his fancy’ (a child after all born to Ruthven, that he cannot get from the ‘dead grey eye’ that looks into no-one and is not looked into in return.

Another puzzle runs through this, from information Stott shares. John’s father, Gaetano, hated Byron’s influence because John’s position reminded him of his own as a youth, at the beck and call of another ambiguous Romantic writer-hero, whom Byron himself used as a model of his public image, the Italian tragedian, Count Vittorio Alfieri. According to Gaetano, such men esteemed themselves ‘far beyond’ their ‘real worth’, but then Gaetano had dropped his desire for fame reflected from such sources.[11] John’s hope for fame remained attached to Byron, and the issue in The Vampyre is that it is difficult to divorce Aubrey’s putative loving care and ‘kind words’ from his possible unspoken ‘smile of malicious exultation playing upon his lips; he knew not why, but this smile haunted him’.

Aubrey being put to bed was seized with a most violent fever, and was often delirious; in these intervals he would call upon Lord Ruthven and upon Ianthe—by some unaccountable combination he seemed to beg of his former companion to spare the being he loved. At other times he would imprecate maledictions upon his head, and curse him as her destroyer. Lord Ruthven, chanced at this time to arrive at Athens, and, from whatever motive, upon hearing of the state of Aubrey, immediately placed himself in the same house, and became his constant attendant. When the latter recovered from his delirium, he was horrified and startled at the sight of him whose image he had now combined with that of a Vampyre; but Lord Ruthven, by his kind words, implying almost repentance for the fault that had caused their separation, and still more by the attention, anxiety, and care which he showed, soon reconciled him to his presence. His lordship seemed quite changed; he no longer appeared that apathetic being who had so astonished Aubrey; but as soon as his convalescence began to be rapid, he again gradually retired into the same state of mind, and Aubrey perceived no difference from the former man, except that at times he was surprised to meet his gaze fixed intently upon him, with a smile of malicious exultation playing upon his lips: he knew not why, but this smile haunted him. During the last stage of the invalid’s recovery, Lord Ruthven was apparently engaged in watching the tideless waves raised by the cooling breeze, or in marking the progress of those orbs, circling, like our world, the moveless sun;—indeed, he appeared to wish to avoid the eyes of all. [1]

The odd things in there is that ‘fever’ is not the only and single effect of Ruthven on Aubrey. In the caring of Aubrey there are lots of elements in confluence: the more than ambivalent effect of Ruthven’s two natures (man and monster), But also the man mixed with the beloved Ianthe, murdered by Ruthven. Every relevant boundary between otherwise irreconcilable boundaries is crossed in this kind of fever-fugue: the dead and the living, evil and good, the perpetrator and victim of crime, male and female, the imagined or real, powerful and powerless, and, privilege and vulnerability. Every point leads to inability to explain but just describe what is ‘unaccountable’ (in a combination of factors) or to attribute a clear’ motive’ for action. But there above all else is the return to the avoidance of being seen into or perhaps seen at all. At one point Ruthven’s point of vision can only be from a stance upon the sun itself, since ‘our earth’ is one of the circling orbs seen.

Is the other binaries compromised here, beside what is seen (and given recognition as an independent subjectivity) and that which is invisible (and ignored as if an insentient object), that of love and hate. For cared for, as he is by a man speaking ‘kind words’ who puts him to bed, he thinks him a ‘Vampyre’. All of that ambivalence may have been in the Polidori – Byron relationship: the latter feeding the former’s illusions of fame whilst not believing in them at all. In the end the ‘victim’ though always gets blamed for the perpetrator’s wrongs. Dead, and possibly by his own hand, but with as little solid evidence of that as with Thomas Chatterton, Byron is eventually told of the death:

‘Poor Polidori’ said Byron when he heard the news, ‘It seems that disappointment was the cause of this rash act. He had entertained too sanguine hopes of literary fame.[12]

Wallace’s ‘The Death of Chatterton’. The model was the poet George Meredith. During the painting Wallace ran off with Meredith’s wife. Meredith produced ‘Modern Love’. Well FAME mattered to him.

Perhaps, we all need to stop seeking attention where it can’t be found – from the world in the form of fame or infamy, or from a lover who barely regards us in fact whatever he says – his eyes fixed on the orbs around his own sun. It’s a thought anyway from the best of Byron’s Romantic poetry, before satire took over:

Love, fame, ambition, avarice—’tis the same,

Each idle— and all ill— and none the worst—

For all are meteors with a different name,

And Death the sable smoke where vanishes the flame.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] The Project Gutenberg E-text of The Vampyre, by John William Polidori, available at: https://gutenberg.org/files/6087/6087-h/6087-h.htm

[2] Adapted from a fragment of Keats first published in a collected edition of 1898 as ‘This living hand, now warm and capable” Available online from The Poetry Foundation at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50375/this-living-hand-now-warm-and-capable

[3] Andrew McConnell Stott (2014: 18) The Poet and The Vampyre: The Curse of Byron and the Birth of Literature’s Greatest Monsters New York, Penguin Books LLC.

[4] Ibid: 152f.

[5] Ibid: 242f.

[6] Ibid: 308

[7] Ibid: 272

[8] I haven’t referred to the recently published Sam George and Bill Hughes (Editors) The legacy of John Polidori: The Romantic Vampire and its Progeny – 1 Oct. 2024, but a look at the search does not suggest development of the Chatterton link through the poetry.

[9] Ibid: 275. The section on the Romantic trope of the foiled author is pp. 272 – 5

[10] Ibid: 146

[11] ibid: 44

[12] Ibid: 278.

One thought on “The fever of seeking recognition is at least one of the characteristics in the origin of the social, or aristocratic, vampire in literary myth. We could all do less fame-seeking! A case study based on John William Polidori’s life and writing, OR …”