Extra time. Isn’t that another way of invoking ‘…the respect / That makes calamity of so long life’.

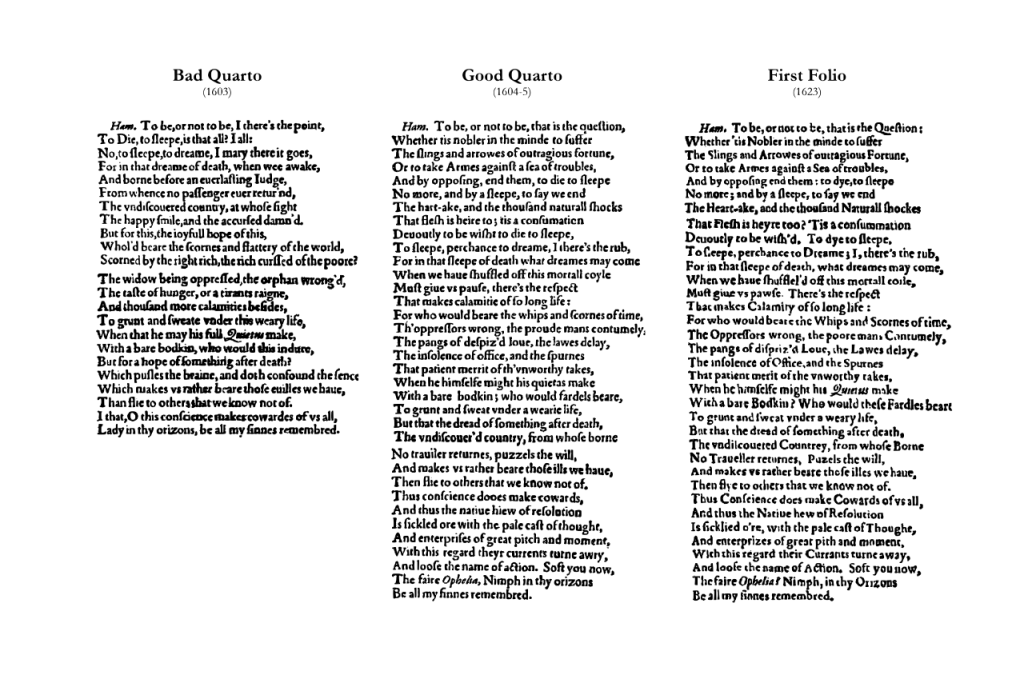

Asking himself whether he had rather ‘be’ or ‘not be’ (in short, die now by his own hand or continue living), Hamlet makes it clear that there is an angle (a ‘respect’) from which having ‘extra time’ would be only a quantitative victory if the quality of your life is bad (see all the versions of that speech for the reasons why below, including the edited version from the First Folio). The Quartos are publications of single plays. Some believe ‘bad’ quartos, and maybe good ones too, might have been transcribed when the play was in production and thus not necessarily reliable or valid reproductions of the intended text.

By Georgelazenby (original PNG), Grufo (SVG) – File:Bad quarto, good quarto, first folio.png, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=168207944

The Folger Library edit the speech thus:

..... There’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

...

Hamlet uses the analogy of death with sleep to mount his argument, though either way the absence of death or sleep would all add up to more time to live the life allotted to you. It puzzles of course that Hamlet, a Prince of Denmark, should see life as having handed him such a poor set of cards to deal – why would he fear the ‘oppressor’, – other than those in the role of his Father abd King, the proud man’s’ poor attitude, being jilted (when Ophelia is just waiting to be asked to become his) and the law and offices of state he commands, or is in line to command, except that he distrusts (rightly) his father-in-law who stands in the way of him ascending the throne, at least immediately. A ‘weary life’, Prince Hamlet – I think not.

However, it is the given of the play Hamlet that the Prince has become depressed and mood on the death of his father and the marriage, soon after, of his mother, and the knowledge – that he can’t help showing he has to his mother directly – that she is having sex (‘paddl;ing palms ‘ and all that) with Claudius, his uncle and father-in-law and may bear children to disinherit him. The latter point is not made directly in the play, but it follows, as surely as ‘night follows day’, that it is the case.

But hold fire! Does Hamlet really think that he has no place in the world of change – the cut and thrust of social life – where the one who stays awake the longest has more chance of plotting to get to the top and stay there. Is Prince Hamlet more like the Machiavellian Richard III than is often acknowledged. Or if that misses the mark as a comparison, remember that, long ago, J. F. Danby showed us that Shakespeare’s ideal of ‘nobility’ and ‘grace’, Prince Hal, and the Henry V, he was to become, were both indubitably Machiavels.

Machiavels scorn sleep for they need the time it offers to plot to make their self-interest the ruling principle of their group or society. Shakespeare makes it clear that the world of the Elizabethsn and Jacobean court was a place where opportunity has to be seized as soon as it shows itself. Sleep is the enemy of such wariness. In Hamlet, even nature teaches us we must not waste time and indeed find more of it to make good our opportunities. Parting from sister, Ophelia, here is the bold Laertes doing what is necessary when he can for some forces never sleep:

LAERTES

My necessaries are embarked. Farewell.

And, sister, as the winds give benefit

And convey is assistant, do not sleep,

But let me hear from you.

Hamlet even begins to make not only an enemy of the death that he had courted in his great sperch quoted earlier. Slerp like eating wastes time. God he says demands we stay awake and lean for action.

... What is a man

If his chief good and market of his time

Be but to sleep and feed? A beast, no more.

Sure He that made us with such large discourse,

Looking before and after, gave us not

That capability and godlike reason

To fust in us unused. Now whether it be

Bestial oblivion or some craven scruple

Of thinking too precisely on th’ event

(A thought which, quartered, hath but one part wisdom

And ever three parts coward), I do not know

Why yet I live to say “This thing’s to do,”

Sith I have cause, and will, and strength, and means

To do ’t. Examples gross as Earth exhort me:

Witness this army of such mass and charge,

Led by a delicate and tender prince,

Whose spirit with divine ambition puffed

Makes mouths at the invisible event,

Exposing what is mortal and unsure

To all that fortune, death, and danger dare,

Even for an eggshell. Rightly to be great

Is not to stir without great argument,

But greatly to find quarrel in a straw

When honor’s at the stake. How stand I, then,

That have a father killed, a mother stained,

Excitements of my reason and my blood,

And let all sleep, while to my shame I see

The imminent death of twenty thousand men

That for a fantasy and trick of fame

Go to their graves like beds, fight for a plot

Whereon the numbers cannot try the cause,

Which is not tomb enough and continent

To hide the slain?

Sleep and cognate images of rest animate that great speech, which show that Hamlet is no man to sleep and eat when self-interest calls. Of course, he calls the latter quality honour. To sleep, perchance to be slain in one’s sleep is the idea, and dreaming barely comes into it. Like Macbeth, he must stay awake. But what of the rest of the play.

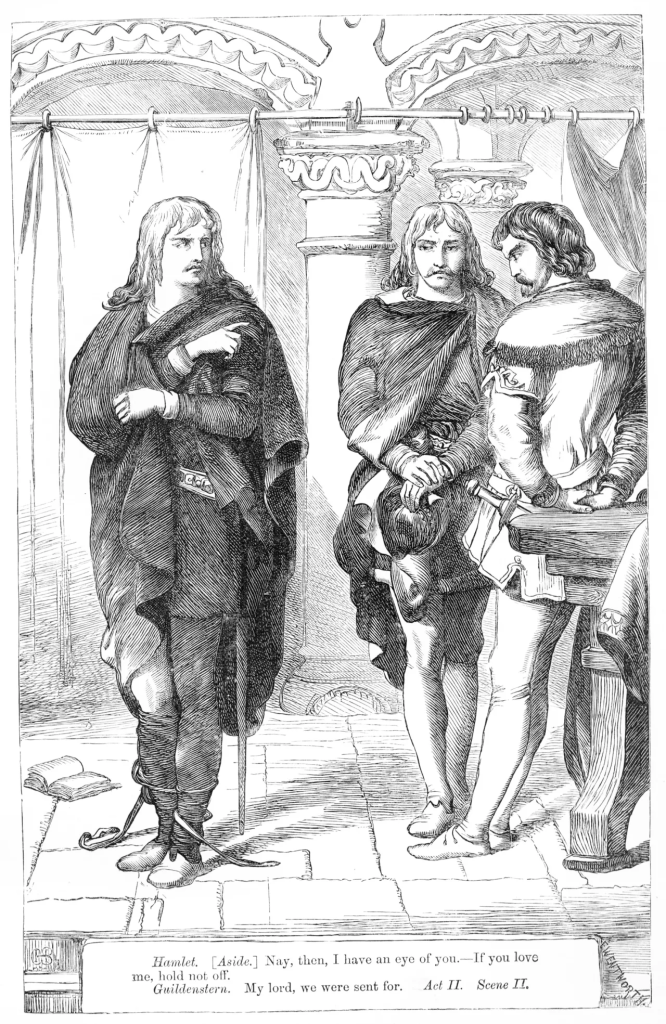

There are other moments that imply that sleep is not the analogue of death but the means of delaying such unwanted absence from lived life. In the following example, ‘extra time’ awake is used to spy out the plots upon our life by those who find our life an inconvenience to them and their interests. As always with Hamlet, his language is heavily sexualised; as if his favoured uses of time were opportunities to rape those around him.

I have always shuddered ambivalently at Hamlet telling Horatio he ‘groped‘ his way to ‘finger the packets‘ of his once university friends , Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, (his ‘desire‘ all along it seems) in order to find them false to him, seeming to be what they weren’t, as he travelled by ship with them to England. He is recounting how he discovered the plot against him – in which his Uncle and King, Claudius, has hired the friends to find ways to end Hamlet’s life. His moodiness is, in fact, a prompt not to sleep, to use extra time to learn how to get the better of those who plot against his longer life and time in the world:

HAMLET

Sir, in my heart there was a kind of fighting

That would not let me sleep. Methought I lay

Worse than the mutines in the bilboes. Rashly—

And praised be rashness for it; let us know,

Our indiscretion sometime serves us well

When our deep plots do pall; and that should learn us

There’s a divinity that shapes our ends,

Rough-hew them how we will—

HORATIO That is most certain.

HAMLET Up from my cabin,

My sea-gown scarfed about me, in the dark

Groped I to find out them; had my desire,

Fingered their packet, and in fine withdrew

To mine own room again, making so bold

(My fears forgetting manners) to unfold

Their grand commission; where I found, Horatio,

A royal knavery—an exact command,

Larded with many several sorts of reasons

Importing Denmark’s health and England’s too,

With—ho!—such bugs and goblins in my life,

That on the supervise, no leisure bated,

No, not to stay the grinding of the ax,

My head should be struck off.

That is a fine bit of verse: ‘There was a kind of fighting / That would not let me sleep‘. Hamlet tosses like a ship in notoriously bad seas until he finds ways to satisfy his ‘desire’. Not only this one but other occasions show us that Hamlet is far from suicide, for he realises that even sleep robs him of the time he needs to ensure that, when surrounded by game players, as many of us think we are in sequences of our life, he stays one step ahead of them, and uses them for HIS purposes, rather than him being used for theirs.

This makes the fact that his father was killed in his sleep by his uncle, as his father’s ghost tells him, an important fact in the play – so important Hamlet writes a play within a play to show that very thing:

PLAYER KING

’Tis deeply sworn. Sweet, leave me here awhile.

My spirits grow dull, and fain I would beguile

The tedious day with sleep.

Sleeps.

PLAYER QUEEN

Sleep rock thy brain,

And never come mischance between us twain.

Even as a playwright, Hamlet pushes the idea that if you find lived life ‘tedious’, you may find your brain not only rocked but extinguished. Once the play is interrupted by the departure of the guilty Claudius and Queen Gertrude, who were its targets. Alone on the stage, Shakespeare pens for him a lyric poem that is imagined as Hamlet’s composition. The theme is to be expected: ‘some must watch, while some must sleep‘.

Why, let the strucken deer go weep,

The hart ungallèd play.

For, some must watch, while some must sleep:

Thus runs the world away.

In the end, Shakespeare uses the hero who many thought his most romantic – not least Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who claimed he had ‘a little spot of Hamlet’ about his character – to be another reminder that the world he comes from one was that the enemy of sleep, rest and refuge from the world. Those who sleep die, miss the tide to leave the harbour, and are the victim of plots, not their makers. Such sleepers can not rule the world. The problem is that in Hamlet, there is one who stays awake more fully than its eponymous hero, another prince, but one named Fortinbrass.

But a world at the cost of rest. Who wants it. Not I. No wonder I never succeeded, as the world measures success. Lol. As for what I would do with the time if I did not sleep. Perish the thought. It is the stuff that makes monsters of people: those who plot while I sleep are welcome to all I could give, whether it be a life or a fingering of my packet.

Bye for now.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx