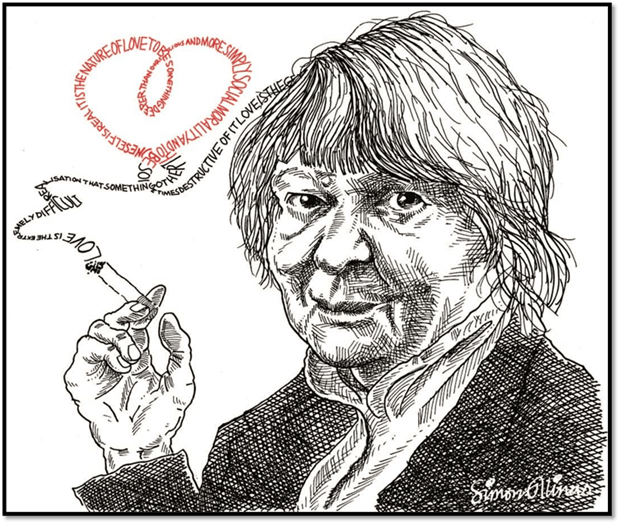

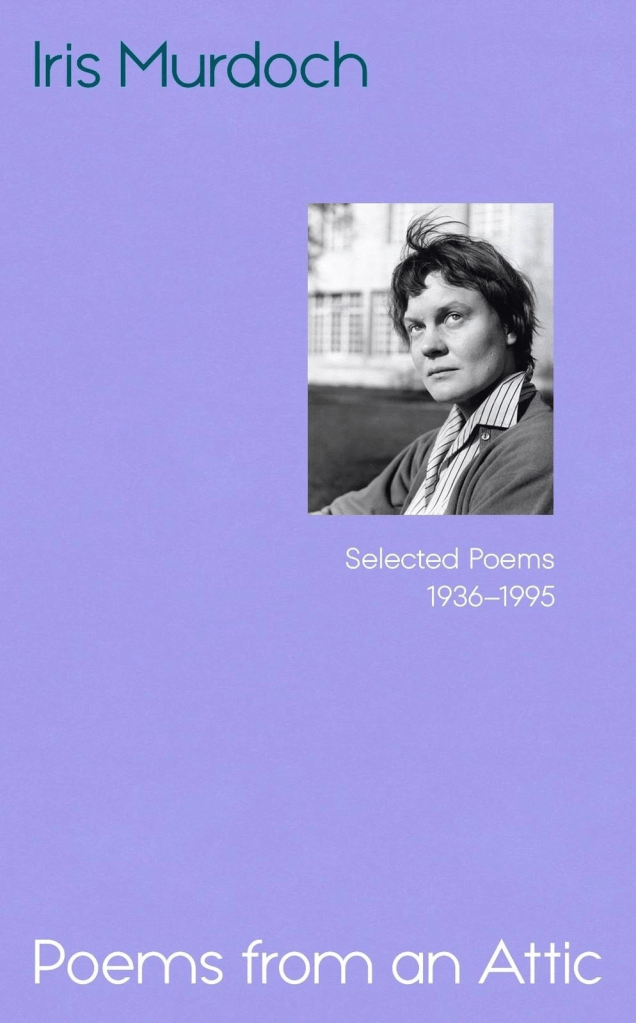

One line in a poem of complicated love between women, written to Brigid Brophy, by Iris Murdoch reads: ‘Don’t make of sex a basic category’. To her journal she committed the following reflection about herself: ‘It’s no good being a female queer, one must be a male one’: This is a blog on Murdoch’s Queer Poetry. Is it a layer of Queer History or the record of a Psychosocial Anomaly? It is based on Iris Murdoch (ed. Anne Rowe, Miles Leeson, Rachel Hirschler & Frances White) [2025] Poems from an Attic: Selected Poems 1936 – 1995 London, Chatto & Windus.

If anyone has read from my series of blogs, they will know I collect books – although I have tried to downsize the collection recently. The collection started with the novelists A.S. Byatt and Iris Murdoch, a very significantly paired set of writers, if separated by nearly a generation. Those collections will never be downsized and when I heard of the publication of another set of her poems, I ordered it immediately. I first thought about the poems in their own right however only in my last blog on one poem, Agamemnon Class 1939, from this, and a previously published collection. See this blog, if you wish at this link. In my collection I have, as well as the books mentioned in that last blog, the first book publication of her poems written at age 18 in a very dull tome named 600 Years of Bristol Poetry, and produced by the local Arts Committee of Bristol City Council in 1973, in which all the poets had an association – sometimes quite slim – with Bristol.

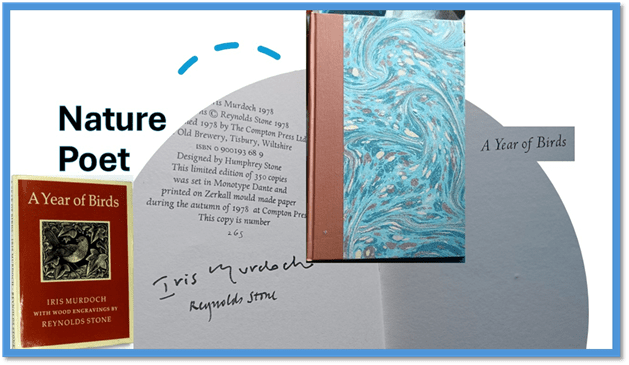

Otherwise I have the first limited edition (as well as first trade edition) of the book she produced with Reynolds Stone, A Year Of Birds, which, as far as I can see is rated by no-one other as verse commissioned to match woodcut drawings. Paul Hullah sees it as like the young Iris’s verse in that they are ‘precise observations of nature’; that is, perhaps because designed’ to accompany previously executed engravings’, the poet’s depiction of ‘image fails to connect usefully with any area beyond itself’, which is the usual role of the image in mature and nuanced poetry.[1] The editors of the present new book of poetry confine themselves on not commenting on the poems in this book, other than to compare them to the ‘more substantial’ collection of poems in Muroya and Hullah’s 1997 collection. To me the word ‘substantial’ reads as much as a qualitative as well as quantitative adjective.[2]

Privately, as the editors of the new volume of Selected Poems, named Poems from an Attic, tell us, Murdoch had tried to discern how to reach a standard of poetry that would ‘delight’ but delight is not, clearly, a straightforward thing. In 1947, she thought delight might derive from these models: ‘- the Metaphysicals. Marvell. Donne. Some Eliot? Browning? A world. A voice. There is some metaphysical unrest expressed in these strange worlds’.[3] It was not like Murdoch to use words lightly and the quality of ‘metaphysical unrest’ that characterises both the world evoked and the voice evoking it would have referenced both of the strands of the metaphysics – the study of what can be said to exist, ontology, and, how, presuming something’s existence, we can know anything about that something, epistemology. Unrest about whether the world evoked in a poem has existence and the validity, and indeed mode of existence, of the voice asserting or even doubting its existence is precisely what the poet wants from her poetry, we might guess. The ‘strange worlds’ of great poetry are queer worlds – nothing can be assumed as expressive of the normative in any sphere. However, this blog aims to focus down on Iris Murdoch as a queer writer, one who might shed light on relationships that break norms and categories – not least in the sexual and romantic domains for these, after all, drew many of us to her novels – to the queer men in them for me, starting of course with The Bell.

However Sarah Hall, in a fine introductory essay on the author, puts some puzzling feelings I have always had about talking about Murdoch’s life and writings as an example of twentieth century queer history case study in excellent context. She says, finding the queer themes and naming them bluntly:

In places, there’s baroque gender wrangling, meditation on self and sexual reassignment. This is an age well before open public discourse on non-binary existence, identity fluidity, bisexuality and polyamory, the assurances of orientation. Perhaps, you might sense though, that even if these distinctions had been available to her, she may not have adopted them, but rather would have continued her versatile, surprising, unclassifiable natures of identification. For all you might pass through a few more layers towards her core via this work, that core remains categorically protean.[4]

I am not sure I understand the term ‘baroque gender wrangling’ correctly but if I do it is a perfect example of what occurs in Conversations With a Prince, that previously unpublished volume of poems in sequence from 1963 published first in the latest revisions and re-sequenced in this book with the addition of the poem I Overcome Love.[5] In fact the manuscript was sent to Norah Smallwood at Chatto & Windus for publication but never published. It rather changes the sense of the whole sequence to add as an editorial decision ‘because ‘it clearly resembles the style and content of the sonnets included there’, which treats it and they as evolved from the poet’s ‘three year entanglement and much longer obsession with the Nobel Prize-winning Bulgarian polymath Elias Cannetti’ during her marriage to John Bailey. Given the autobiographical slant the editors find in the poems, the editors decide that the embodied personification ‘Love’ in many of them is Canetti himself – the lover not the abstraction implied in the name ‘Love’, though still with a singular visceral body, notably in that wonderful poem I Overcome Love. After all, in that austere poem the figure embodied as ‘Love’ is, till his defeat and assimilation into his victim or object, predominantly and performatively male, as for example in the lines below which the editors tell us mirror Dante’s conceit of being floored by desire.

Love was triumphant and he arched upon Me like an eagle pinning to his prey, And shook me, and his flaming tresses spun Like lightning in my backward turning eye.

They compare this to a note on her love-making with Canetti from her April 1953 journal: ‘C. made love to me savagely, tearing my clothes off … I told him he was a great gale, and I was a tree in a gale’.[6] The wrestling here is visceral not just because of the flexion in the semantics of the words but the dramatic turns of position as the male embodied Love takes the victim / object a tergo, such that he/she can only look back at him under the weight and pressure of the event. The main problem with reading this poem is that we carelessly think of the love object, as ‘she’ and ‘her’ rather than as of unspecified sex/gender, a subject asked endlessly whether they prefer to identify with ‘those who are weak’:

“… Not accidentally, My dear, its mine to crow and yours to cower! Those who are weak are those who come to harm.” At this point he began to twist my arm. I was in pain. ….

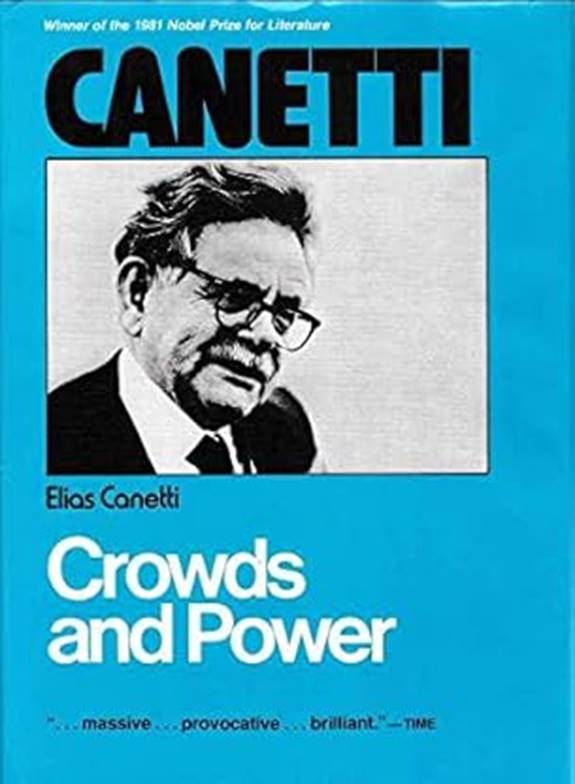

As powerful an image as this is, I do not think it helps to equate the male presence to Canetti, or to Canetti alone, and certainly not only in terms of physical power and violence. After all Canetti’s work itself has, although it is clearly more than a simple metaphor for psychological pain – rather it sees all pain as ‘embodied’ together with its origins in paranoid fear of huge masses.

We are enmeshed currently in a culture, with a feminism that calls itself radical where it means simplistic, that is obsessed with the notion of biological sex and a relation between the sexes mediated by bodily advantage – weight, volume, mass and power to hurt. That idea is part of the issue addressed by feminism but not all of it since Mary Wollstonecraft, wherein whose work the introjection of femininity with an etiolated content that implies that the feminine is a secondary and victim status is the real enemy of female assertion of power. Such ideas are not unlike the analysis of the power of crowds or masses (or fascism) in Canetti’s book Crowds and Power, where the crowd is empowered by the fear of the individual to individuate itself from it and risk being its victim.

Hence rather than look for the he-man in Canetti in these poems in ‘Love’, and the consequent victim status and even the feminine in the lyrical ‘I’ voice, and equated that with Murdoch who was no wilting flower, I prefer to read them as poems in which sex/gender or some other positioning of strength and power is forever being negotiated, even (more strictly) viscerally wrestled over, as in the wrestling between Jacob and the Angel in the Old Testament(see my blog on this cultural theme here) – alluded to more perfectly and fearsomely in her sonnet Chartres Angel: ‘Here is the angel that you strove with, Jacob’. It is only when both ‘Love’ and the ‘victim’ are both terrified, because the lyric voice bearer says that they know Love’s ‘real name’ (the manner by which Rumpelstiltskin is overcome except I think the name of ‘LOVE’ in these poems is ‘POWER’) thar Love almost magically loses its sex/gender and implicit differential performative assumptions:

… His strong embrace Was loosened suddenly, and terrified The god and I were kneeling face to face Like animals for slaughter in one tether Huddled and shivering we clung together.

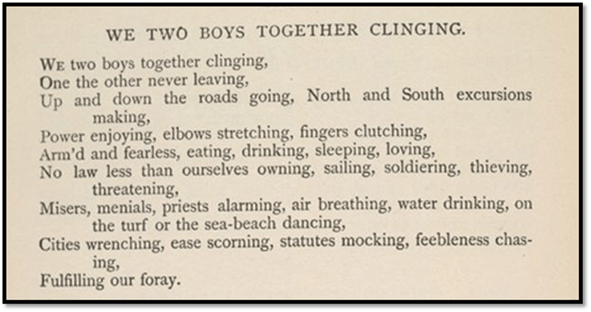

Do you hear , as I do, an IRONIC echo at the end of this poem of Walt Whitman’s poem We Two Boys Together Clinging, ironic because in Murdoch neither figures is any longer ‘enjoying’ Power together nor ‘feebleness chasing’ in their own right or in alliance – indeed rather the reverse, they are sacrificial animals:

Indeed overcoming ‘Love’ In I Overcome Love means overcoming any strength or power to survive: learning to accept the slaughter meted out in the abattoir of human life. Strangely enough the point is made in relation to a classical Latin, poet, Propertius, in the poem preceding this in the sequence Conversation with A Prince, the poem delineating Absence as a phase in loving by a ‘witty’ play, not unlike those of John Donne, on the meaning and function of telephones in modern loving, You By Telephone. Here are the lines;

I can see the point of Propertius’ desire for perpetual fighting, Nam sine amore gravi femina nulla dolet, But I prefer to see the person I’m kicking and biting When I am in the arena whose bounds by Love are set.

The editorial notes to this poem translate the Latin as ‘For without serious love no woman suffers pain’, which somehow robs the line of the effect of its double negative, which makes femininity conditional on being the one who suffers pain (and subjugation) in love. My reading of these poems sees the lyric voice as wrestling and debating with Love to find a position as a subject that is nearer to Whitman’s ‘two boys’ (or perhaps Jacob and the Angel) than to a woman subjugated to a violent male lover. Implicitly I am arguing that Murdoch’s feminism rejected the analysis of femininity as subject to masculinity, but rather than fighting the pressure in women to feel the inward inferiority to men projected upon them and to grow into equality. I am not denying, as Murdoch would not have done I believe, that there are structural mechanism by which men hold power over women in society, just that only women who do not identify as subject victims can challenge those external structures.

Women are set to fight with men as men until such a point and this lies behind some famous statements by Murdoch about why she did not identify as a lesbian. Of course such matters are nuanced and the editors in their critical essay are correct to say that, because such openness about attraction to women in a woman in her times, though not illegal, was made difficult by all kinds of social barriers, conventions and mores, and stayed unknown to her readers, except those in the know, was ‘unknown to her reading public’ until her authorised biography by Conradi in 2001 revealed much after her death, that she acknowledged what animated her own relationships, and those more frankly of the characters in her novels, was the dual taboo nature and undeniability of queer sexuality. Yet we would be wrong to say Murdoch talked in code of some relationships because of fear. For what was more taboo than the easy identification of a singular orientation and basis of relationship was the fact that they were for her hard to categorise because open to such permutation. The editors quote her personal confidential letter to logician George Kreisel:

I can’t divide friendship from love or love from sex – or sex from love etc. … I am probably not at all normal sexually. I am not a lesbian, in spite of one or two unevents on that front.; I am certainly strongly interested in men. But I don’t think I really want normal heterosexual relations with them … I think I am sexually rather odd, which is a male homosexual in a female guise. [7]

The only excluded option is what we might now call hetero (or homo-) normativity, that depends on the strict categorisation not only on the appropriate object of a relationship for each of the binary sex/gender categories it recognises but also on appropriate classifications of relationship type – friendship, romance, love and sex-based. To her journal, a year after saying the above, the editors cite the following reflection about herself: ‘It’s no good being a female queer, one must be a male one’.7 I think Sarah Hall places all this coded and open discourse (as in the novels after all) brilliantly in saying that her discourse lived across a divide that she recognised as the complexity of real lives, where even the interpersonal and intra-personal are difficult to distinguish from each other. When she refuses openness it is because openness is not the truth of the matter. Honesty is a difficult thing because it is not because one has a hidden agenda or plot. Here is some of what this brilliant novelist says about another such:

Sarah Hall Introduction Page xiv

And note in that piece that other complication in her poems – their refusal to find normative mediation or description of relationship, which divides its pains from its pleasures, its game-playing from its frank seriousness. Hence the play with what Freud analysed in the specialised ‘perversities’ – relating to objects (shoes are an example in Conversations with a Prince, where she tries to divert Love by saying his roughness has made her lose her shoe – a bit like the Angel maiming Jacob, as in The Word Child) or manner of expression of closeness and distance, freedom and constraint, pain or pleasure in embodied love. It’s all in the analysis by Hall: ‘“Honesty is a hard thing,” Murdoch notes in these pages, though she does nevertheless hope to be tethered as “truth’s prisoner in the end!”’.[8] The editors collapse some of this into the way complicated self-hatred play with ‘a frisson of sado-masochism’. Although there is more than enough of the same imagery in Conversations With A Prince, they actually apply this description to another earlier poem, dedicated to an earlier and lesser person than Canetti (though with an heroic enough set of first names, William Wallace Robson.

The poem’s name is Tu es mon mal (Thou art My Sickness – I archaise the translation here to capture the power of the first person singular in French), a phase she used of Robson, though calling him too her ‘cure’. The editors say: ‘This extraordinary poem catalogues deviant emotions that were to titillate her imagination …’.[9] I rather balk at the term ‘deviant’ and even a little at ‘titillate’, although she was never beyond titillation. Deviant however places her love poetry in the box of the psychodynamic confessional – naming its perverse secrets. Tu Es Mal does contain a catalogue of potential perverse sources of sexual pleasure, as do other poems: including branding, mutual cutting with knives, bondage, selective violence, visceral wrestling, bruising, cauterising, flaying or electrifying the receptors of the nervous system, but violent processes can be as easily metaphors of psychological pain and indeed the effects of inner emotion as the physical sensations they also evoke and actually feel like in the body. categorisation. And, perhaps more important – these are metaphors that are deeply political, showing power at its most naked as the thing that binds down its victims and frees them to greater pain later at a whim. Look, for instance, at this:

I can see no hope in your sex branded eyes. Our extreme unction is a lack of hope. Is this the future’s flesh, its innocent shape, Kernel of lightning in collapsing skies? You are the troubled and dark power counter To which setting foot and knee I strain Until I define myself in a rending pain And see in shock my soul’s fragments founder. Shot through the head into a diamond glory. Promised not present – there is only a shiver Along the nerves. The notion of never Is an unformulated part of the story.

What, after all are ‘sex-branded eyes’ (which I dare say also suggests ‘the sex-branded I or egos of the category of ‘love’ one expects from the other.). The idea of a branding mark laid on the skin is certainly a kind of suggestion that Robson as a lover was a man who wore a scar like mark – one perhaps that Murdoch felt he needed to warn off any lover who did not want to be ‘sex-branded’ too – either as a ‘woman’ (and what women meant to men in the 1940s) or as a sex-object. After all this is a poem about the pain or pleasure or some configuration between the two oof being ‘defined’ (having a boundary created around one’s person and body) even by yourself. I do not think, with the editors, that ‘you’ merely denotes Robson, it is the power of sexual categorisation as the inferior feminine.

However, it also defines Robson as unable to fulfil the passion that the lyric voice potentially hopes for in love: for that voice finds some ‘promise’ in ‘rending pain’ and being fragmented from the conventions into which life has cast them. If it talks being shot through the head to find ‘diamond glory’ in some sexual or romantic unction or investiture of the soul. Nothing the sex-branded’ type of love Robson can give is ‘present’, it is only ‘promised’, and the lyric voice suspects has an ‘unformulated’ narrative as its get-out clause, where Murdoch will never achieve the satisfaction, in any domain or across them, she yearns. After all the point of the poem is not to brand Robson as ‘bad’ (that kind of ‘mal’) but as unlikely to understand the free spirit in her that will always arouse his nasty jealousy, something John Bayley avoids throughout their marriage, although his posthumous memoirs of his wife show it was potentially there:

The darkness in me of untruth to you, Your jealous force that weighs upon my neck.

No-one wants to stay Under the Net (for nets are out to catch the lyric voice in the first stanza of the poem: ‘The dark nets in the dark waters move. / This is but an image of our love’) or wear such a weighty halter, least of all Iris – no wonder she liked to think of herself as a queer male lover of males; other categories were a kind of bondage and robbed her of power, even to mount her own fragmentation and painful Orphean sparagmos, defining ‘myself in a rending pain’.

And the issue applies to being categorized as a lesbian too for Iris, or indeed anything else – except for that impossibility (for her in that culture) of being a ‘male queer’. The poems that speak of this are the two dedicated to Brigid Brophy. The notes to this book tell us the ‘women became deeply emotionally involved in the1960s’, although unlike Robson, ‘remained friends until Brophy’s death in 1995’.[10] The beautiful sonnet To B, who bought me two candles as a present is woven around the notion of a relationship that bounds the other (for all endurance is bondage but not therefore necessarily unwelcome) but also undoes the bond at the same time ‘with perpetual art’. But the greater poem I use a line from in my title: For B, who tried to persuade me of something in a somewhat Freudian metaphysical poem. The line I use sounds like an injunction and addressed, as I think it is to Brophy’s (and perhaps her own – for nothing in this poem’s argument gets settled about how finally to conceive of sex/gender in a world where the laws of power distribution are hegemonic over everything) confusion of nonbinary thinking (or at least ‘mixing of the sexes’) and suiting herself in nominating the other with whatever sex/gender label she chooses.

Don’t make of sex a basic category

This feels powerful, although in the evolving syntax of the sentence that is it’s context it is merely a statement of the I, representing Murdoch here without a doubt, claiming how and why she disagrees with ‘Freud and all his patter’. What the lyric voice insists is that everyone tries to bind you to a category for their specific interests or exercise of their power to get what they want.

…. It’s quite confusing. You want me female, then you want me male, Or else hermaphrodite, to suit your choosing, While for yourself you have some other tale Of corresponding moves.

Let’s clear up the burning question in the title: Why a ‘metaphysical’ poem’? Murdoch invokes both uses of the term – the description given to seventeenth lyric poetry, notably that of Donne which used the manner of argument to unfold its beauty: usually clever elaborations of a poetic image or ‘conceit’ masked as argument, and he name of the branch of philosophy engaged in questions of the nature of being and knowledge of it beyond or above the merely physical world. If you were to look for a metaphysical poem (Freudian but well before his time and itself before the usual application of the term to Donne and such) that matched those confusions, you would find one that is surely referenced in this poem. I stand by the referring for surely the line, ‘Something to your purpose in me lacks’, surely echoes, in my ear anyway Shakespeare’s: ‘And by addition me of thee defeated, / By adding one thing to my purpose nothing’), that is Shakespeare’s Sonnet 20.

Murdoch was an avid reader of the Sonnets as shown in the essay in this book, but not in this respect. But Sonnet 20 is a kind of inverted Sonnet 20. Written by a woman to a woman, it necessarily inverts some of the jokes about possessing a penis or not – hence Freud (the least philosophically metaphysical definition of femininity but horribly current in our world of facile ‘culture war’ and the elevation of the simple mind of J.K. Rowling to that of a supposed sage). The ‘something’ to Brigid’s purpose that the lyric voice lacks in body is precisely that penis – to allow her to be male and an hermaphrodite physically speaking, whereas in Shakespeare’s man-to-man poem both Shakespeare and his lover are ‘prick’d out for women’s pleasure’ theoretically speaking and the fact becomes a problem.

A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted, Hast thou, the master mistress of my passion; A woman’s gentle heart, but not acquainted With shifting change, as is false women’s fashion: An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling, Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth; A man in hue all hues in his controlling, Which steals men’s eyes and women’s souls amazeth. And for a woman wert thou first created; Till Nature, as she wrought thee, fell a-doting, And by addition me of thee defeated, By adding one thing to my purpose nothing. But since she prick’d thee out for women’s pleasure, Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.

But note that all the things Murdoch says Brophy wants her to be, Shakespeare has not made his male lover already in his poem (‘a woman’s heart’, a beautiful man and a hermaphrodite (‘master mistress of my passion’). But just as Shakespeare ends his sonnet with a sort of representation of mutual masturbation (I’d blush to work out the arguments) so does Murdoch as each lover loses themselves in the other’s forest or bush – neither idea need be taken literally of course:

For what it darkly is, then take my love And in the forest lost we still shall rove.

It’s all meant to be ‘witty’ in the sense of the Elizabethan poets, but it is also about the denial of sex as a category, whether it describes sex/gender or the acts potentiated between people we call sex. It is about moving above physical category of sex to something nearer to Murdoch’s not very ‘normal’ definition of relationship – where love, friendship and sex are confounded as well as sex/gender binaries.

There are other poems in the collection that diffuse sexual categories. One of my favourites is The ‘Acropolis Korai’. It takes up the idea in the poem to Brophy that women have been buried by male cultures (imprisoned and fettered), fully conscious that the male kouros was the more feted of the Greek archaic art that included both those and the female kourai by the Classical period of the Greek Acropolis. It is a poem about the downgrading and burial of female potentiality but also about a hidden space in which women have ‘slept together, the broken limbs and the faces / And the delicate hands and feet in the crushed dark’. That is the ‘secret of their shuttered places’ and is not a simple picture of oppression and bondage by men though it evokes just that because it is a truth. What they also an ideal of the queer female that is, as it is not in the ‘tortured heads’ and ‘ashamed hearts’ of mid twentieth-century AD women – and why the latter find only the model of being a queer male a possible model for a woman independent of categories. It is the most beautiful evocation of lesbian love I know – a love where the mouth sings embodied tender enfolded wisdom, as the NeoPlatonist did, as well as being:

… incredible lips, the trembling Poise and subtle tenderness of mouths, and the knowledge Strangely stored in a cheek’s curve. ...

However, I started this blog with a promise to speak of the book that never became such Conversations With A Prince. I think Sarah Hall’s general conclusion about the poems as a whole is true of this ur-book, in a passage from her ‘Introduction’:

Love is embodied. … Love becomes more significant than a lover, even. Submitting to the truth of the feelings, to the emotion and power and meaning it brings, if not to a human candidate, is in a way the ultimate truth to be found within this book, should one still be needed.[11]

Love is not personified but embodied as God is incarnate in Christ not personified, as the Christian NeoPlatonists insisted. I do not know, and I do not think we are told – even Conradi did not in his masterly biography, plying that she saw them as the work of more ‘a versifier than a poet’[12] – the meaning of the book’s machinery of subtitles offered in the reprint in this book. However, this machinery did seem to me meaningful as a structure, though I may be being entirely fanciful (or the sub-titles not even Iris’s). The account of the poem in the editors’ critical essay in the book has fascinating insights but illuminates only the underlying autobiographical analogues of the poem sequence, which still seem to me not the poem sequence itself and in some way diminish the poetry. The structure of subtitles could be tabulated thus:

| Sub-title & my brief description | Poems included | Pages |

| Declaration The existence of love before it is articulated or when it is otherwise unspoken because of some distance between the speaker and its object. | Reading of Palms Refusal to Sing Word Watcher Forest Fire ‘How far is the green cliff’ Pine Branches The Shell (2) | 63 – 70 63 64 65 – 66 67 68 69 70 |

| Encounter Poems of meeting and parting illustrative of love encounters | Picture on a Table-cloth Oxford to Paddington Ravenna ‘The sun has left the garden’ Winter Snapshot | 71 – 76 71 72 – 73 74 75 76 |

| Absence Unembodied Communication across distance after encounter and before resolution of the relationship. | You By Telephone | 77 – 78 77 – 78 |

| Conversations With a Prince The meaning of love in various case studies | I Overcome Love (added by editors) Overheard Love Keeps the Maze I Seek for Love at the Carnaval Love Makes My Heart A Shrine Love Visits His Traps Love Solves a Problem for Me I Attempt Escape I See Love in Bad Company Love Sights a Wreck I am Consoled by Love I Meet an Old Friend I Encounter my Old Master Love Brought Down Love Smiles Upon Us | 79 – 95 79 – 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 |

| Remembrance The aftermath of broken love and its continua. | A Fallen Tree in the University Parks Nightingales near the London Road Snowdrops | 96 – 99 96 – 97 98 99 |

As I reread the poems I found the brief descriptions I give above some help but I do not hold out great belief in them. Nevertheless, they do show, if they are original to the typescript submitted to Chatto & Windus that they betoken a narrative sequence that is centred on the study of the ontology and epistemology of LOVE, moreover one that holds out the belief that LOVE is cognate with the art of telling stories about it in many media, all of which are considered within this volume. Within this the study of the wrestle that Love involves itself with in becoming one with the human predicament is central. Love is an Angel who can be at one with configurations of pain and pleasure, fiction and reality, evil and good, death and life. But Love must be tested against power – both over-pretension to it or failure to assume enough of it to survive or to learn that it is the source of illusion until we share and sometimes usurp some of its power to help it and ourselves survive.

Somehow these poems are a kind of meta-art, that show that the more we work on our art the freer it and Love can be to redeem us. Consider Love Keeps the Maze, in which the labyrinth, that old Greek symbol of art imprisons those who do not ‘foil the old design’ and try to fly like Icarus. If you stay to say: ‘I am the slave of monotonous feet’ (surely the feet of the very regular iambic pentameter in which this line is written)’ , you are the poet who is ‘Following the same pattern every time’. That poet will never become learned in Love’s (or art’s) ways, including his subterfuges, and love, and write poems freely slipping out of their skin when necessary. The poems after these in her life were written in much freer verse.

I have to end this then no wiser about Murdoch as a poet or enabled to make any reader wiser (should there be any such readers) but humbled enough to see she was a poet not a versifier. This book has done us all a favour.

Bye for now

With love

Steven xxxxx.

[1] Yozo Muroya and Paul Hullah (1997: 39) Poems of Iris Murdoch, Okayama, Japan, University Education Press

[2] Editor’s Esay in Iris Murdoch (ed. Anne Rowe, Miles Leeson, Rachel Hirschler & Frances White) [2025: 138] Poems from an Attic: Selected Poems 1936 – 1995 London, Chatto & Windus.

[3] Ibid: 139

[4] Sarah Hall (2025: xiv – xv) ‘Introduction’ in Iris Murdoch (ed. Anne Rowe, Miles Leeson, Rachel Hirschler & Frances White) [2025] Poems from an Attic: Selected Poems 1936 – 1995 London, Chatto & Windus, xi – xvi.

[5] Iris Murdoch (ed. Anne Rowe et.al) op.cit.: xvii (Editors’ note on text)

[6] Ibid:150.

[7] Ibid: 146

[8] Sarah Hall op. cit.: xii

[9] Iris Murdoch (ed. Anne Rowe et.al) op.cit.: 145

[10] Ibid: 157

[11] Sarah Hall, op.cit: xv

[12] Peter J. Conradi (2001: 579) Iris Murdoch: A Life London, Harper Collins Publishers.