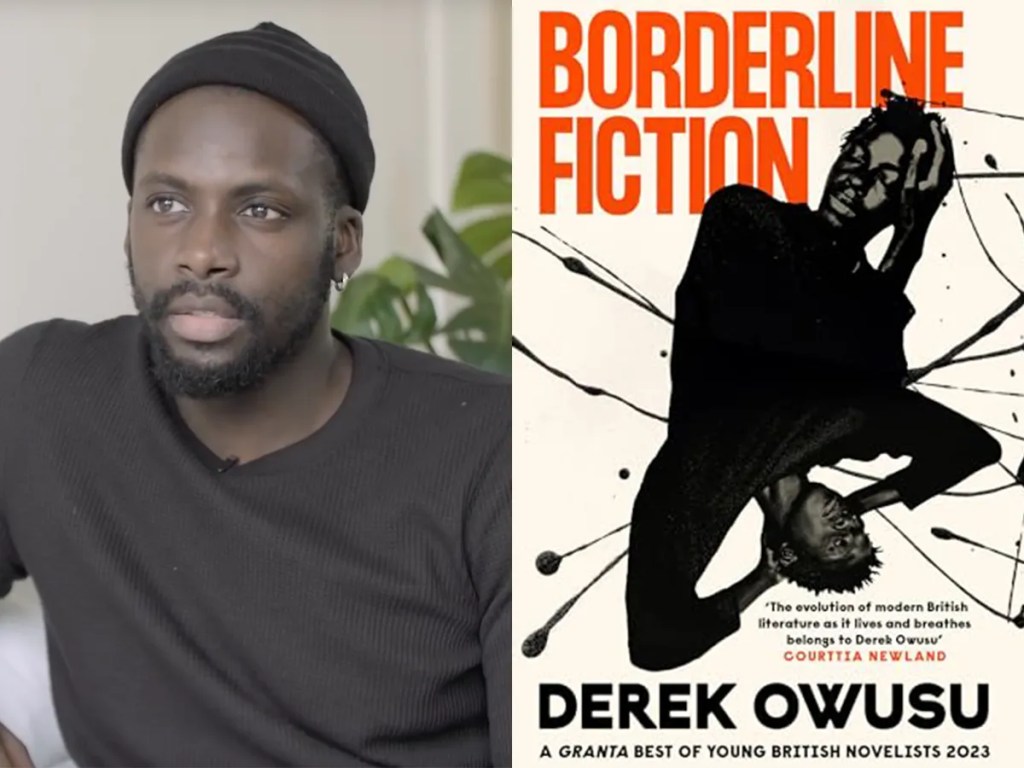

‘A pervasive pattern of instability of relationships, self-image, and affects and marked impulsivity, …’: Are DSM-5-TR Categorical Criteria means of describing a person, a character, an author, or a reading experience ever? This blog reflects on Derek Owusu (2025) Borderline Fiction, Edinburgh, Canongate.

As yet, I have discovered no ‘professional’ critical view of this book, although I don’t look beyond paywalls or other exclusive barriers like those used by The Guardian in lieu of a paywall. However, in this case, this has allowed me to think about some issues raised by another amateur, like myself, Andrew Blackman, whose honesty of approach requires some praise, despite the fact that his view of the literary is one basically unfriendly to Owusu’s narrative and descriptive methods in the novel and uneasy about the experience of mental disturbance is conveyed. This is his summary position I think:

Then we have the issue of spending an entire novel inside the head of someone with Borderline Personality Disorder ‘[Steven’s note: BPD Hereafter]’. This is why I return to the line I started this post with: I found a lot to admire but not a lot to love. It’s worthwhile to see life through the eyes of someone with BPD, but it’s not very enjoyable. I found myself losing focus, forgetting which timeline I was in, and often not particularly caring what happened in either of them. Borderline Fiction was an interesting read, but not one I can honestly recommend. It was too uneven for me, too repetitive, too meandering. [1]

Blackman gives lots of examples meant to support his critique of the book, but a reply from a respondent naming themselves, BuriedInPrint [9 October 2025 at 2:04 pm] takes Blackman to task for appearing to put his own readerly enjoyment ( desire for a “good read”) over being offered unique access to:

how one figure experiences the world through the prism of a BPD diagnosis, and it seems like that would be an uncomfortable place to exist? And, if that’s true, maybe the question of whether prose is repetitive or meandering just isn’t the question to ask? If his intent was to depict an authentic experience, wouldn’t being less repetitive and more structured be inauthentic?

Blackman replies:

On reflection, “good read” probably wasn’t the right phrase. I don’t think Owusu needed to smooth out his narrative or make it inauthentic. I do think there could have been a way of showing the authentic experience of a character with BPD in a more successful way. [1]

And there you have it! Blackman, backed into a corner, has to insist that it isn’t that he does not want access to the ‘authentic experience of a character with BPD’ but that he wants it to possess a certain literary quality he finds absent in Derek Owusu’s writing. Examples of people with fragmented consciousness he uses to shoe he can enjoy them if done well enough are Dostoevsky’s The Gentle Spirit (‘written’ he says, ‘from inside the disordered mind of a deeply sick character who’d just driven his wife to suicide’), Milkman by Anna Burns, and C by Tom McCarthy. In these cases, Blackman says,’the narrative was fractured and difficult to follow, but I enjoyed the reading experience. The difficulty was worth it’.

But I don’t think Blackman does himself any favours in his further explanation and elaboration. His point remains that the only access we want to mental disturbance is one we can see as that of a ‘deeply sick character’ or otherwise fractured consciousness that is ‘worth’ something in other terms than access to experience alone, in a ‘successful way’ as adjusted by someone looking for something that appeases a reader without intetest per se in the mental disturbance or fractured and damaged consciousness. The odd thing is that Blackman does feel the novel does illustrate the effect of BPD diagnosis yet as a symptom of the disorder rather than as exploration worthy of either a reader or writer. This is hid description of the symptoms illustrated:

unstable interpersonal relationships, acute fear of abandonment, intense emotional outbursts, self-harming behaviours, risky activities, dissociation, a pervasive sense of emptiness, and a distorted sense of self. [1]

Blackman need not have looked very far for his knowledge of the clinical description of BPD, for Owusu’s novel itself cites the entry for it in DSM-5-TR (the volume pictured below), from which I quote in my title:

A pervasive pattern of instability of relationships, self-image, and affects and marked impulsivity, … (cited Owusu page 291)

Personally, I have for a long time been critical of both the validity and clinical application of diagnostic descriptions such as this, but this catch-all one in particular, though not as much as persons who have had experience of being thus diagnosed thrust upon them, because it singles out the cause of perceived fractured relationships as one located entirely in the psychology of one person rather than an interaction with pre-structured imbalances and tendencies to stigma and scapegoating in the dynamics of social psychology.

Characteristically, people diagnosed with BPD are told that their feelings of not ‘fitting’ into society are solely those brought about by the mental health condition that they as individuals have. Hence, when Blackman explains his sense that the imagery used by Owusu’s narrator to ‘fit’, my ears pricked up. Into what precisely does the imagery not fit? Is there a prescribed ‘container’ into which imagery fits? Is such a container bounded by something like or analogous to the good reader’s sense of what good writing is. All this begs so many questions but Blackman’s use of his sense of ‘what good writing’ is NOT certainly asks us to believe that his intuitions are not only those of a ‘good reader’ but of one capable of knowing what words ‘fit’ in good writing and which do not; For instance, he examines a short piece of Owusu’s prose thus (Blackman’s quotations from the novel are in italics):

Some of the writing is beautiful, but it also tends to pack in a lot of different images that don’t always seem to fit. Here’s the opening paragraph, to give you an idea:

So, yes, I was in love again, losing balance, stumbling towards an earlier phase of my life. It was a moment I thought I knew, one I thought I could distinguish from my grazed and swollen knuckles as I fought back vertigo, the peak of a desert where a person became a thing.

It’s quite poetic, but what exactly is the peak of a desert where a person became a thing? It’s hard to visualise, especially since it later turns out Marcus is at a speed dating event in London. Vertigo is a familiar way of describing the feeling of falling in love, but what comes afterwards just makes it harder to situate the scene. The grazed and swollen knuckles are explained later on, if you’re paying enough attention: Marcus used to bite the skin of his knuckles, so it’s a powerful way of showing the character’s anxiety.

At other times, the poetic language disappears, and we just get pages and pages of dull and repetitive dialogue or circular arguments, with no attribution or quote marks, so that it’s difficult to follow who’s saying what.Something told me you were hiding shit from me.

Something told you?

Yeah?

Like what?

I don’t fucking know, I just know when someone is doing me dirty, something just tells me.

Really? Something like what? Anansi?

Are you fucking dumb? Why you chatting shit? What the fuck, man?

That ‘vertigo’ is sometimes used to describe ‘the feeling of falling in love’ does not suggest a thought that helps anyone trying to read a prose text as it is rather than what we think it ought to be. My own response to ‘the peak of a desert where a person becomes a thing’ is to accept its indication of both vast empty vistas seen from an unstable eminence where even the ability to distinguish between persons makes them things. Its virtue as a metaphor is precisely that it cannot be visualised or objectified, it is all about the world emptied out of clear perception of our place in space znd time, dizzyingingly realised. Yet the desire for real usable images, called by T. S. Eliot ‘objective correlatives’, are precisely that kind of images are unavailable to the mind of a man like Kweku or the writer he would become, for it is a mind abandoned to abstract empty space:

Feeling the absence of God, when existing became too real, when I could see life without it being lived, when I was without my meds for too long, I imagined how we float in space, many planets alike, stars, fragments of worlds, galaxies, possible universes, like the discarded words on the page of a frustrated writer, a watchful but tearful God blinking away the tears and thus flittering us all in and out of existence. [3]

Of course lots of the features of BPD , as listed in the excerpt from DSM-5-TR in the appendix of the novel, characterise this prose – the radical sense of abandonment (by God – and other Fathers – and mothers too), the sense of vast empty space uncertainly inhabited, by things or persons, of a base instability in things even existence. But what strikes is that the whole of existence is like the process of writing and editing ones writing – which includes the erasure of text as well as its laying down as text on an initial blank space. This is is what Blackman misses – the novel is absorbed in a constant querying of the ways that telling and hearing stories, writing or reading them are associated with the processes of reflexively lived lives, lived in the mirrors of shaping consciousnesses.

Vertigo is, after all, most commonly the description of an experience that medical history and art have attached to the deregulation of our sense of the perceptual world, attributed sometimes to ‘anxiety’ (a reading Blackman also invokes) or more specifically derealisation, associated with anxiety but also with writing that fails to ‘find its objective correlative (as Shelley did according to T.S. Eliot). In such mental states the world feels disassociated from both self and reality, a place where persons and things are interchangeable (as we shall see happening with those knuckles of the narrator, who sits beside him in the coach travelling from Thorpe Park as if a person independent of him, before San takes Knuckle’s place on the seat beside Kweku. Later still, when Kweku takes up running, he does so with ‘wide-eyed Knuckles, wired Knuckles’. [3.5]

In vertigo, moreover, things and persons get absorbed by self and confused in their perceived status of mobility around it. Typically, things spin or spiral around the self, sometimes decentering the self through the forces we call centrifugal.

Hence, it is not a state where attribution of speech may even be possible to the derealised consciousness hearing and seeing such possible ‘othernesses’ that might also be aspects of the self. To attribute all this to BPD is typical of psychiatry but not of attempts to understand an experience if you have not had it yourself. Nor is appropriate of prose with the aim of inducing a kind of literary vertigo to say, as Blackman does, that you can’t ‘visualise’ its imagery. Look again at the novel’s opening partially (the first two sentences) quoted by him:

So, yes, I was in love again, losing balance, stumbling towards an earlier phase of my life. It was a moment I thought I knew, one I thought I could distinguish from my grazed and swollen knuckles as I fought back vertigo, the peak of a desert where a person became a thing. I remember I was still, stood staring at the girl who had just walked into the hall. She had a unique fringe of braids, 8 that covered her forehead and then curled around to fall back with the others, hiding in plain sight, so stunning but shielded. She had the delicate face of a statuette, high cheeks that balanced light, everything working together to illustrate features that could be shattered if you weren’t gentle enough, a face baked under the sun inspiring shadows. A nose she hated for its European shade – though only in the light of the colonial could it cast such doubt – and lips that looked thin until gently coaxed from between her teeth. I think her eyes were blue, purple in some lights, like poetry turning its back on the prosaic, but they would always change colour whenever I tried to remember them. [4]

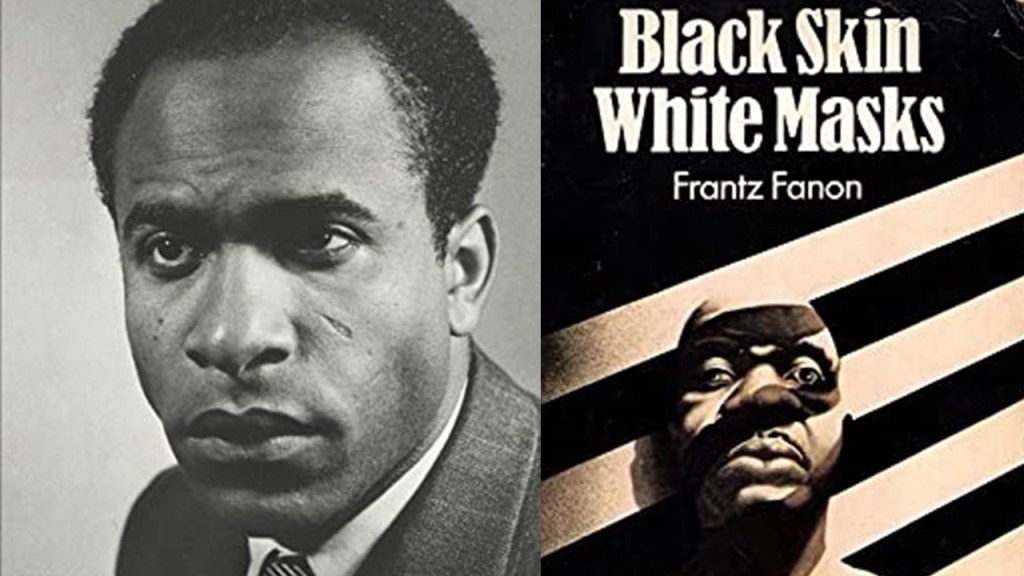

Blackman points to the fact that meanings here are hard to find if what we look for is not only the visual but the coherent. But ‘losing balance” and dislocation in space, time and in relation to objects, even objects forming ‘part’ in conventional terms of the embodied self, like knuckles is precisely evoking a background context of felt incoherence as its aimed-for effect. Similarly we find it difficult to place ‘the girl’ (who will turn out to be San) in time, space of in terms of fixed characteristics – even the perceived colour, in shifting perceptual time-spaces of memory – of her eyes> likewise we cannot grasp attitude that shifts from that of the colonised – hating the colour shade that falsely identifies herself to the imagined gaze of others as ‘European’ to one of the internalised ‘colonial’ (only later do we learn that San reads Franz Fanon and wishes to lend a copy of Black Skin, White Masks, together with many other ‘Bibles’ of Pan-African thought, to Kweku.

Later we shall see the term ‘vertigo’ used to characterise the modes of thought of Pan-African critique of colonialism. San and Kweku see a film about the governance of Zimbabwe on Independence with speakers discussing the film’s political important to Black consciousness in the context of the ‘games of the white world’ to a majority Black audience:

Someone involved with the film who had refused to take questions before we left preluded the opening scenes with pride and clarity for the undertaking, had explained that after years of doing as the white establishment required, lying prone while it extracted what it needed, he had now reached a point of acquaintance with vertigo and was able to pull the people and ideas he thought needed more exposure up to the platform.[5]

There is a stunning re-translation in these sentences, which themselves do not have any clear frame of coherent reference invoking pictures of pride and submission alongside each other as each other’s explanatory context, but not with any clarity of the actions they describe, of the term ‘vertigo‘ from a symptom (of anxiety or derealisation) to something induced by the double-bind of a racially-white-serving ideology that had suppressed Black voices and stances.

I also found the ‘paranoia’ of the narrator at age 19 (the novel is divided in normally subsequent chapters between him at ages 19 and 25, about Adowa ‘hiding shit from’ him (also cited by Blackman (in the second example of the book’s lack of clarity for him) deeply believable. That dialogue is entirely consistent with the sense of certainty, false or otherwise, of feeling in 19 year-old Kweku that ‘someone is doing me ‘dirty’, that there are social mechanisms that alienate some kinds of neurodiversity (and even of individuated or marginalised experience) in persons. Likewise his apprehension that Adowa is referring to the deep fear of his father in her reference to Anansi – the spider so linked to his father’s, and his own, erratic behaviour as a compulsive addict and liar, including his compulsion to generative fictive storytelling. This is, I think, all about how the novel handles and looks at the aetiology of symbolic discourse, in human socialised and formalised speech, art, and the cusps between these related discourses. Yet, as with most BPD sufferers, those aetiologies are reduced to stigmatised personal responsibilities for a fragmented self or ‘personality’.

As evidence of this we know that other people, including writers (and Black writers in particular), do see something more interesting occurring in Owusu’s prose in this novel. Indeed, Blackman even quotes one such whilst adding, rather unnecessarily, that he has met this artist himself: ‘Courttia Newland, who I met in Barbados years ago and whose opinion I respect, said’:

“The evolution of modern British literature as it lives and breathes belongs to Derek Owusu … With this novel, Owusu doubles down on everything that makes his fiction so exemplary. There are passages that took my breath away. The world, the dialect, the ideas, are all glaringly fresh and true.” [1]

Courttia Newland

My sense of the novel now I have read it is with Newland, I think, despite the seeming hyperbole of being responsible for the living and breathing evolution of modern British literature. This blog must try to put things right in my take, as opposed to Blackman’s, on the novel; re-centering it on issues of the storying of humanity, and particularly Black male humanity in stories of supposed psychosocial malfunction, especially those in privileged psychiatric accounts, like DSM-5-TR (how typical that Owusu go for the most recent revision of that professional psychiatric manual).

But before doing this, I ought to admit to a speculation of my own based on an early published version of a chapter draft from Owusu’s writing that has now become this novel. I wrote in response to its publication of working extracts from the Granta Young Novelists novels-in-progress in 2023. For the text of this blog, see this link. The Granta story, entitled Kweku, is now not easy difficult to locate in the novel as it now stands and the queer content, though still there as an undercurrent of queried queer – ‘questioning as it is is sometimes called – is minimal to the point of vanishing, even though it never was there in the extract except as a supra-cultural ambiguity, contributing to the querying of sex / gender. It omits altogether Kweku waiting to be ‘picked up’ or any other like use of the phrase (in the sense of being sexually selected by another person at a venue in which such things occur – like pubs). Indeed, the only use of being ‘collected’ from somewhere by others in the novel is when he is ‘picked up’ by his cousins from an addiction recovery unit. There is no longer present the shifting identity of the man who does the picking up readable in the Granta draft. Kweku, in the published novel, is in fact not named till near the end of the novel.

Nevertheless, odd references to queerness remain and are hard to explain. At one point, Kweku in conversation with San, ‘without thinking’ asked ‘her if she had ever loved a woman’. He gets no answer: ‘she looked at me and bit her lip and told me, in her way, the evening was over and I shouldn’t be so interested in other peoples’s lives’. Although San apologises in case she was ‘rude’ to Kweku later, the reader remains as puzzled by the source of interest in that question or San’s amorous past: the novel leaves us with this moment as if it were an example of the kind of inappropriate questioning, it seems, can be expected by her from Kweku. [2] Otherwise, we cannot know how, or how much, and why this question of the possibility of queer love interests Kweku. His close relationships with men tend to ones of biological or extended family , in the sense of community as family, although I sense some questioning at points of how these are understand, they are sub-textual. The queerest male-to-male relationship is that with a male unknown to him that he meets on a train – meetings structurally significant because at either end of the novel – whom we learn to named Nana, a Ghanaian word associated with chieftain or leadership paradigms, though much emotionally charged ones than the analogues in normative White English. [5]

The first meeting with Nana is with an unnamed and unrecognized stranger, who is woven into the unstable and collapsing feel of things and persons, such that Kweku takes some Zanax almost in response to the way the man’s proximity to him destabilises him:

On the train ride home, the carriage was full, but I’d managed to find a seat with someone looming above me preferring to stand, their knees buckling every so often, teasing a collapse into my lap, and I imagined them falling into me like a ghost inhabiting my body. His back was to me but I sometimes glimpsed the white of one eye followed by the dark pupil trying to turn and look at me. It was unnerving, and to elevate the feeling I imagined the eye turning all the way round into the back of his head, watching me above the closure of his hat. I took another .25 of Xanax and leaned my head against the window,… [7]

I just don’t know how to read that ‘teasing a collapse into my lap’ for it is certainly over-warm in its homo-sociality, given these are strangers, and how then to read the notion of Nana ‘falling into me like a ghost inhabiting my body’, in the manner of the Gothic doppelgänger. I can’t help find the cusp normally in fantasy literature here between the homosocial and the homoerotic, though nothing else in the troubled exchange (on this occasion and its repeat near the end of the novel) evidences that in terms of described behaviours or conversation. Instability of perception and relationship, as sensed by Kweku, there certainly is. Do we call this symptomatic of BPD – a ‘borderline’ phenomenon between fictive and real? I don’t, but does the novel invite you to do so?

And if the behaviour on this occasion isn’t erotic it is certainly queered:

Calm down. He was looking at me like I was asking for something and he was disappointed he couldn’t offer it up, like someone else would help, he was sure, but he was saddened it couldn’t be him. His face was reflective, light entering the top corner of his window seat revealing whatever he used on his skin, handsome somehow, a face you couldn’t look at for too long, though, without giving yourself away by the silence, something secretive in its appeal, one of them faces you would be hesitant to show to others because you knew they wouldn’t see it. As he leaned forward towards me there was a ring swaying on a chain around his neck that caught the same window light and illuminated an engraved snake around the outside with its mouth open towards its tail. [8]

Queered and romanticised in a very literary way, this paragraph ends with a close-up of the Ouroboros symbol hanging at Nana’s closely focused-upon, by Kweku, neck, that I imagine as beautiful. That there is something ‘secretive in its appeal’ may launch us back into queer readings of such encounters, where the queer is deliberately socially marginalised. We don’t see Nana until 250 or so pages more and again on a train, in transit between fixed places and times. Again he emerges into the familiar, although never quite that, from the disembodied uncanny – at least in Kweku’s perception:

So as I turned, slowly, I saw a face, there as if disembodied, one unafraid to be looking so directly into my own, one I didn’t expect to know but could see that with a change in the size and distance of features he would be vaguely familiar. [9]

And ending the novel, the prose that mimes Kweku’s consciousness allows the figure of Nana to flit into that of his girlfriend, San, waiting for him at the destination train station at Bolton (we have to quote at length here). The figures flit into each other for we never understand why it is so important to work out why Nana thought there was an ‘awkward’ feature to the way they interacted, or why sexualised behaviour with San needed Nana’s capacity to distract.

I knew San would be waiting for man at the station and I couldn’t wait to see her and just lips her for the first time and tell her how I felt and then we could try and work things out, I had a good feeling, and just thinking about her made my entire body tingle and I swear I could see flashes in my eyes as if a lightning bolt was close, and I was shaking a lot now and wished my man was still on the train, distracting me and actually he was a cool guy and I’m not even sure why he thought things were awkward before. The train started moving and I slid up against the glass, put my fist to it to spud Nana if he turned around. Man like Nana, you know. Listen, you see Oscar Wilde, I remember they used to say he was a great conversationalist because talking to him, he made you feel smarter than you were. Man like Nana made me feel more me than I had in a long time. Crazy. Those are the typa man you gotta keep close, I should have got his number. I watched him walk down the stairs and he did look back but while he was turned is when he disappeared. So then I just sat back and I let my head fall onto the headrest again, closed my eyes, my body feeling like it was spilling out to fill the carriages before and after me. [10]

Why, moreover, is Nana made into a model of Oscar Wilde as a conversationalist? Except that Nana made Kweku ‘feel more me than I had in a long time’. Yet of homoerotic content, there is none. Of the queer and the crazy there is plenty. Feeling fully accepted (by San, by Nana – by the Pan-African perhaps which he talks about with Nana and San) his self is neither abandoned and empty as in the BPD symptomatology but ‘spilling out to fill the carriages before and after me’, through time and space.

I mention the African associations here because it is a novel so concerned with the viability of Pan-African traditions, mythologies and stories. Their meanings matter. And, if I think anything about the fact that what will not go away in the novel is the overt insistence that the characteristics of BPD contribute to the characterisation, plot and themes of the novel. However, do they pose themselves as a description of personality and character validated in the communicated experience of Kweku, or does that experience, as intuited in the character Kweku and sensed and filtered cognitively and emotionally by a reader really put a question mark over the validity and reliability of knowing someone by a multi-criteria psychiatric diagnostic category, the description of a mental illness, and perhaps see it in the context of trans-cultural conceptual conflicts? This is how I intend to approach the novel, where the sexual queer remains merely a potential to what might be described as an inconsistency, instability or questioning of personal self-understanding, another thing that White Northern and Western culture has marginalised. No matter how you talk about the themes of the novel: either the aetiology of BPD or other psychiatric labels in the enforced suppression of other cultures, especially in the socialisation and training of ‘yout’ (the word the novel uses from Ghanaian Pidgin English for ‘youth’). If I return to Blackman for a moment, it is interesting to see that he lavishes with ‘faint praise’ the ethnographic content of this novel:

I also liked reading a novel in which British-Ghanaian culture is at the centre. Both Marcus and the women he falls in love with are from that background, and it’s not a perspective you see too much in fiction. It’s reflected in the food, the culture, the conflicts with the older generation, and in the language: both the interspersing of often untranslated Twi phrases and the London lingo: “handing out leaflets in ends, taking man’s numbers, belling them and asking if they thought they’d go heaven.” [1]

Yet there is something reluctant in the praise. I agree that ‘untranslated Twi’ can lose a reader without knowledge of that or other Ghanaian languages, but that sense of being lost, and abandoned by codes you feel ought to be familiar is not only the stuff of BPD according to psychiatry but to any situation where superior power privileges languages that are denied to those not given or denied access to them. In fact language and ritual that exclude, confuse and empty out the world of the marginalised is a theme of the novel as much as BPD is. Let’s look at this passage; the one that introduces Kweku’s father, whose mental illness will be seen as visited on Kweku:

My family wanted me close to him, I knew, because they believed I could help change him, bring him back or push him forward, I’d never really known. But still, all voices seemed to converge to convey something solid, warm, a golden consistency they hoped to stay surrounding our selves, the richness of our origins closing in on us. But it wasn’t true. I could see through the fabric and only one man sat on the stool: my dad. This was one reason for my distance, my coldness. But couldn’t I listen to him talk, they asked, now that I’m okay myself? I know how it began, why they began to look for me, my aunt had told me, recalled it like a story, told me how my mum had returned home early from work, left when her students did, could plan her classes from home. She’d crept through the back gate, slowly stepped through the kitchen and then hesitated, paused, listening, imagining, a student, her favourite, finally reading aloud to themselves in the absence of an audience. My mum was home and he was awake, unaware, like child left alone babbling on its back, but heard from the other side, through a wall or breach, heard turning his words on himself, reliving and repeating something his mother had said to him when he was a boy maybe, in Twi, in Ga, in Fante, in Ewe, but without love, without narrative, without balance, silenced only when he emptied his glass, a clash from trembling hands just as it was refilled. [10]

Asked to redeem his father from mental illness because he, Kweku, had now passed through it to some recovery, his family assert the resilience of youth and the strength of community, community in the model of family. No one has defined the imposed myth of community that haunts marginalised and migrant groups than in these phrases: ‘all voices seemed to converge to convey something solid, warm, a golden consistency they hoped to stay surrounding our selves, the richness of our origins closing in on us’. ‘Can something warm also something frightening and claustrophobic?’, these phrases ask! Can be asked to be the conduit of warmth induce coldness? The prose forces these terrible things onto us. That Kweku’s dad was ill was as much a tradition passed onto him by his family experience and that such illness reflected the condition of nor knowing the language adults talked to him, those Ghanaian languages listed in the passage: Twi, Ga, Fante, Ewe. Kweku’s Mum – socialised into white educational practice barely knows how to invite her husband back into their supposedly shared family. Yet she colludes in getting her son to do this without the same resources thrown into the BPD symptoms of the alcoholic’s emptiness and lack of ‘balance’. Surely Blackman might have noiced that it is not all about Twi. Let’s look at another passage, once in the pre-published Granta chapter too.

My dad reached for the gin, pretending to pour some in my mouth like libation, the lid still fastened tight. Then came voices like they were once whole but now split into unequal parts: Hey hey, he’s too small, come on, mfa mano. Eiiii, he has come! Who has come? Bra Nancy! Whan? Obarina wei? Wɔ ferɛ, ana? Heh, gyae saa, wo nkanfo no too much. Kojo, find space, let him sit. C’mon, my dad said, let me correct my money and go. Around the table were Uncle Dave, Uncle K, Uncle Charlie, Uncle Kojo, Uncle Sam, Uncle Kwabena, Uncle Kofi, Uncle Tito, Uncle Ata one, Uncle Brobby and Uncle Wofaa. Uncle Dave and Uncle K sat opposite each other, heads down, watching the beads of the game. They looked up to greet and click with my dad – I saw so many hands reaching for him at the same time that day, and somehow he managed to satisfy them all. I was put into a corner, sat upon a stool, climbed and stood and stretched to see him over the lives, the bodies that crowded around him. But he shouted for me to sit, and so I watched the backs of the men, forgetting their faces so imagined them to be as my dad’s was, unaged, smooth dark skin like a mask, beneath which there was something someone was always searching for. I tried to pick up words I’d heard before and draw new ones from their proximity to the ones I knew. The last time we had come here I picked up the word koromfou. This was the day I’d learn its meaning. [11]

The only meaning I can find for koromfou in Twi (but is it Twi?) is ‘cornmeal’, but the point is not whether that is so but the confusion and challenge to our basic sense of what it means to ‘now’ the world that unknown or untranslatable language throws us into at any age. The passage above is especially an example of the strengths Newland finds in Owusu’s prose: ‘the world, the dialect, the ideas‘. And it is not only Ghanaian dialects and languages that count here. Google translate failed to help me with: ‘Whan? Obarina wei? Wɔ ferɛ, ana? Heh, gyae saa, wo nkanfo‘, even in determining which language it came from, if, indeed, it was from only one Ghanaian language and / or dialect. The effect comes in reading this passage from my ignorance and confusion for it mimics that of the young Kweku, unable to understand the worlds into which his father takes him, having to make assumptions about the details of the lives around his Dad from their unrevealing back views, finding Fanon-like masks, if Black ones. The reader picks up words as does Kweku, coming out with no certainty of having understood what has passed. And note that this does not apply just to African languages. It starts with a libation, a word with a Western history from which modern meanings are selected and reconfigured with old ones. Here is etymonline.com:

libation (n.) : late 14c., “pouring out of wine in honor of a god,” from Latin libationem (nominative libatio) “a drink-offering,” noun of action from past-participle stem of libare “pour out (an offering),” perhaps from PIE *lehi- “to pour out, drip” (source of Greek leibein “to pour, make a libation”). / This is from an enlargement of the PIE root *lei- “to flow” (source also of Sanskrit riyati “to let run;” Greek aleison “a cup for wine, goblet;” Lithuanian lieju, lieti “to pour,” lytus “rain;” Hittite lilai- “to let go;” Albanian lyse, lise “a stream;” Welsh lliant “a stream, a sea,” llifo “to flow;” Old Irish lie “a flood;” Breton livad “inundation;” Gaelic lighe “a flood, overflow;” Gothic leithu “fruit wine;” Old Church Slavonic liti, lêju, Bulgarian leja “I pour;” Czech liti, leji, Old Polish lić “to pour”). Transferred sense of “liquid poured out to be drunk” is from 1751.

The modern meaning might satisfy us here, except that the scene mimics a ritual in which his father seems the God from which the gathered ‘Uncles’ (communal uncles of course not strictly – that is, in the White races reductionist sense – biologically familial ones). And Dad is a kind of God, he is Anansi, whose story is told in one chapter, but reference to whom is everywhere and where both Dad and Kweku participate in spider-like descriptions of them, their mode of being and storytelling as so much weaving of narrative thread. [12] Early on we see how Dad identifies with a spider against his wife’s violence to those creatures:

Up until this point, my dad’s tenderness, those bursts from his indifference, I measured by how closely he watched my mother as she moved around, searching, a school shoe or steel toe in her hand, how he’d recoil then rise at my mum’s attempts to kill a spider. This small spider and you’re using such a shoe for it? [13]

Later, that identification makes Kweku hate the very qualities that make his Dad into Anansi, at least in the latter’s drunken self-projections as a story-weaver:

The funny thing is, I’m not even embarrassed by him when he’s drinking like that, I’ve been around bare people who drink and throw up and act like the version of them I know is resting while this next version is having fun, so it’s a minor. It’s when he starts talking and getting into stories, immortality, spiders and death and how he’s got venom inside him and all this other shit. [14]

For a moment look at the adjective ‘bare’ in this passage for it is often used in the novel – a word from Gahanian Pidgin English, employed in the UK. [14.5] Used here it also bears the thematically (in a ‘BPD novel’) meanings empty, blank or exposed. Later again, we see that Kweku sees his Dad as Anansi not only because he oft told those stories but that all the stories he told were handled in the manner of a spider-like storyteller:

I remember many of the stories my dad told me, about his past life, about me, about the spider himself, details not so distinct with the latter two, but their emotional resonance stayed with me, I guess only to remind me and intensify the moments they existed in, moments that held me like an embrace, but on the face of it the nostalgia kept me encased. One story he told me, on a day he and my mother came to visit me in care, one about Anansi the spider, is one I can recall verbatim, but I think that’s because it’s interwoven with something else that happened, spun in the same moment.[15]

Note the metaphors: ‘interwoven’, like the fabric of a web, ‘spun’ as a spider spins silk. They soon proliferate (spinning, cocoons, as here, where I give only excerpts, where the theme of ‘lies’ told by a father inhabit the trickster persona of Anansi, the spider-God who stole(‘took’) his stories from the Sky-God:

At home, he’d lie watching the world spin, cocooned, awaiting his life before birth to return without death. … My dad was a storyteller, took his words from the sky, I could believe it all sitting here watching him twitching in his sleep, all lies believable when the speaker stops speaking them, finally pinned down to a real time and place. But a story, like deceit, or myth, is never finished. [16]

What I think is clear is that BPD cannot provide the description of a person masked as a disease nor even describe a reader’s experience of that person and their stories. At age 19 Kweku seems to believe that BPD explains both his fear of death as a form of abandonment (a thing diagnosticlly-inclined psychiatrists would plainly assert) and says so to Adwoa:

… I’m honestly surprised I’ve lived this long. I always thought I’d die as a teenager.

Why?

BPD. Thought I’d kill myself.

What’s BPD?

Borderline Personality Disorder.

Like you have different personalities?

No.

Then what? Can I do this line or you want it?

Yeah, it’s fine, you can do it. And, Marcus, you know I love you so take this with love, but I don’t want to talk about mental illness stuff right now. Because I know if we start talking about it then we’re going to be here all night talking about it, you know? Let’s not bring the mood down, okay, so enough burying the world in rubble for today.

Fine.

But I do want to know what it is that scares you about death?

I don’t really know, you know.

Are you sure, Marcus?

Yeah?

Does death feel like the world is abandoning you when you think you need it most?

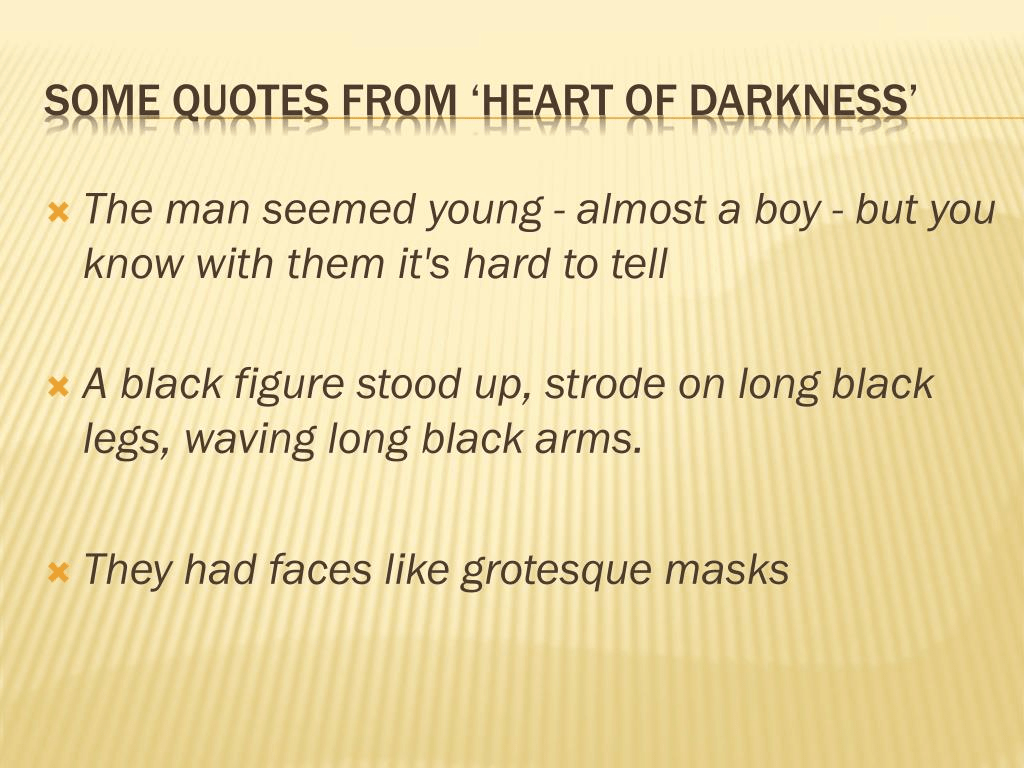

The misunderstanding of what BPD is is just one level of misapprehension here. What is wrong with it as an existential description is that it ignores all the factors in the traumatic making of Kweku that he can reveal as he ages into the sections of the novel where he is a more mature 25 and can cope with revisiting his real experiential multiple abandonment (now not just ‘borderline fictions’): an alcoholic father with unresolved issues, a split in his parents’ relationship, being fostered several times, oddly useless mental health therapy, and, not least, white racism and marginalisation. This is why this novel is so great and why it is is not, as Blackman thinks, badly written. Even in academia, people mistake experimental prose for bad prose. This book even addresses this by examining Kweku’s reading of the borderline racist, Joseph Conrad (alongside inexplicably Ralph Waldo Emerson), finding things in sentence structures that more ‘correct’ readings of Africa, such as those of Chinua Achebe, might miss.:

Pushing up through my back pocket against the concrete step were the two books I’d been reading, Heart of Darkness and Self-Reliance. This was the second time I was going through Conrad. The first time had been a struggle. There are some sentences that stop you, some words that feel so out of place you can’t read past them the first time around. You have to go over a sentence again and again until your mind adjusts to this new texture and you can move on. I had adjusted and was now enjoying the read-through, the narrative distance and decline, finding myself disagreeing with what I believed to be the best work of prose our grand-uncle Achebe had written.

Looking at the examples above, it still seems odd that this may be so even when some Conrad sentences can be sen as nothing but the worst kind of racism. Did Blackman read that passage in Owusu however? Did he respond in doing so to his own feelings of ‘struggle’ with Owusu? I just did that – it is my way with reading and I cannot change it now at 71. It is not a satisfying characteristic; struggle never is. But I believe in Owusu as a writer and follow his writing with that faith intact, doubting myself before he. This blog has been even more of a struggle, so I will leave it there – for my aim is only to learn not to teach. If you read this then, forgive me.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx

_____________________________

[1] Andrew Blackman (2025) ‘Reading Borderline Fiction by Derek Owusu: I wanted to like this novel, but I couldn’t. Here’s why.’ By avatar, Andrew Blackman, 7 October 2025,

8183, available at: https://andrewblackman.net/2025/10/borderline-fiction-by-derek-owusu/. The italicised quotations unpaginated in the quotation are from Derek Owusu (2025: 1 & 141 respectively) Borderline Fiction, Edinburgh, Canongate

[2] Derek Owusu (2025: 152f.) Borderline Fiction, Edinburgh, Canongate

[3] ibid: 32

[3.5] ibid: 127

[4] ibid: 1

[5] ibid: 164

[6] ‘In many parts of West Africa, there is an old chieftaincy tradition, and the Akan people have developed their own hierarchy, which exists alongside the democratic structure of the country. The Akan word for the ruler, or one of his various courtiers, is “Nana” (English pronunciation /ˈnænə/). In colonial times, Europeans translated it as “chief”, but that is not an exact equivalent. Other sources speak of “kings”, which is also not entirely correct, especially in the case of the said courtiers. The term “chief” has become common even among modern Ghanaians, though it would be more correct to use the expression “Nana” without translation wherever possible’. from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akan_chieftaincy

[7] Owusu 2025 op.cit: 30f.

[8] ibid: 35

[9] ibid: 282

[10] ibid: 50f.

[11] ibid: 287

[12] Anansi’s story is ibid: 229ff., but the descriptive language elsewhere often evokes the spider, and his story – including stealing his stories from the Sky-God.

[13] ibid: 53

[14] ibid: 87

[14.5] My AI tool gives me the following text on the meaning of bare in Ghanaian pidgin: ‘Bare in Ghanaian Pidgin English is translated as “just” or “only.” For example, “I dey there bare” means “I’m just there” or “I’m only there”. It can also be used to emphasize a lack of something or a simple, basic state. Here’s a breakdown of how “bare” is used:

Meaning “just” or “only”: English: I’m just hungry / Ghanaian Pidgin: “I de hung bare.”

English: That’s just the way it is / Ghanaian Pidgin: “Na bare way e be.”

Meaning “simply” or “nothing more than” / English: I just want to eat / Ghanaian Pidgin: “I bare wan chop.”

English: It’s nothing special / Ghanaian Pidgin: “E no be something bare.”

Adding emphasis to a state of being: English: He’s very tired. / Ghanaian Pidgin: “He be tired bare.”

English: I’m very happy. / Ghanaian Pidgin: “I be happy bare.”‘

[15] Owusu 2025 op.cit: 92.

[16] ibid: 205

[17] ibid: 148

Very appreciative of how you engage with my work, Steven. I’d like to send you an advance proof of my next novel, due out in September 2026. Shoot me an email if you’re interested. Thank you.

Derek

LikeLike

I would love that Derek. Your writing is so wonderful. The old guy here is really appreciative

LikeLike

I have written to your agents email to express my interest. Thanks again

LikeLike