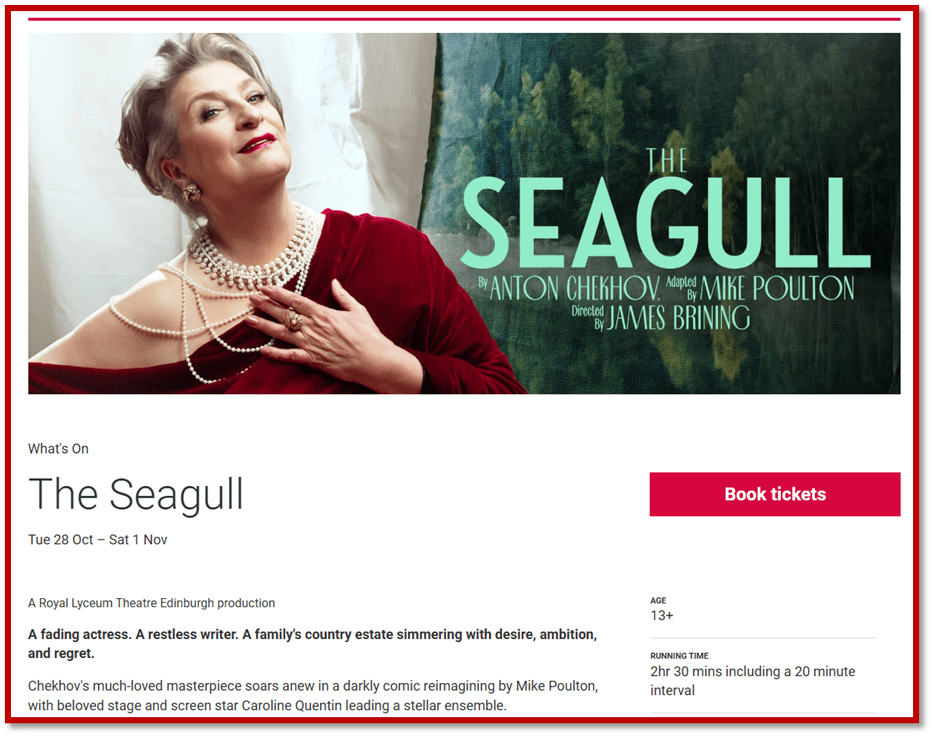

Innocence is not the condition of childhood- rather it is inability to control the heart or stop it from being overwhelmed. This truth is embedded in the reflexive nature of Chekhov’s great play The Sea-Gull. In Act IV of The Sea-Gull, we hear of the stage in a country estate’s garden that in Act I is thought to be capable of playing a part of the renewal of theatre but by the end of the play ‘stands as bare and ugly as a skeleton’ on which the ‘curtain flaps in the wind’ and that hence feels to a passer-by ‘as though someone were crying in it’. The Sea-Gull might be a young child’s lament for Russian art (that of the theatre and the novel) that is ‘false to the marrow of’ its adult ‘bones’ and might as well give up its quest for a glorious role in Russian development into an adult future? [0] Why is it important then to revive The Sea-Gull on the modern stage? This blog is an attempt to prepare myself to see a revival of the play at The Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh on Wednesday 29th October at 2.30 p.m.

No doubt John Poulton’s version of The Seagull [my preferred spelling but not used in this blog which refers to Constance Garnett ‘s translation] that plays now at The Lyceum in Edinburgh will stand some distance from that of Constance Garnett’s translation that I have just re-read, but that is to be seen and heard when I see and hear the play on Wednesday. But I was pleased to re-read the play, for otherwise I would have been haunted by reading it last in the sixth form in the1960s. I hadn’t been aware then how much the play focuses on writing and performance art careers, the comedy involved in its description of those careers. Hence I will speak of that aspect before examining its plea for serious writing to ‘grow up’ and not wallow in the overwhelmed responses to the world of adults who, for some reason or other never could grow up or develop in a way that is resilient to being knocked back for being over-demanding.

The underlying idea of a serious writing that can be sustained in the real world of fictive appearances is spoken out most by a medical doctor. As in Uncle Vanya (see my blog at these links for Part One & Part Two respectively) real social passion (passion for the green and watery natural environment full of natural life) and the drive for change and recognition of change inheres in a medical professional. Chekhov was himself such a professional for much of his working and professional life, before his seduction by the Russian Bohemians and the pull of Western art forms to match his native feel for Russian social comedy. Yet to grow up Chekhov seems to have to come to terms with adult seeming and use it to coat his message rather than rant on child-like in the background that the world is ‘not fair’.

There are a number of artists in The Sea-Gull, always at least two of each kind; one older in age than the other. Actor performers are represented by Irina Nikolayev Arkadin – or Madame Treplev – (played by the great comic actor Caroline Quentin in the performance I will see) and the aspirant ‘country-girl’, Nina Mihailovna Zaretchny. Conversely writers are represented by both Irina’s younger lover, the Boris Alexeyvitch Trigorin, and her no less Hamlet-clinging-to-her-Gertrude like son, Konstantin Gavrilovitch Treplev. It is this last character who bears the burden of being the artist who cannot grow up – aware of truths but unable to live with them resilient against their denial by those who benefit from a world that masks the danger their lives of luxury and false appearance pose to the natural world. The childlike refusal to develop is a theme pursued in Treplev, who, together with his mother, is locked into an Oedipal self-absorbed drama, like (as Chekhov obviously believed) was Shakespeare’s Hamlet with his mother Gertrude – another overwhelmed child kept so by his mother. I will look at this key theme and support it, in line with the prompt question later.

But now for more on the role of art, artists and their appreciative (or otherwise) audiences in this play. More than one character claims skill as an art connoisseur though none so significantly as the medic, Yevgeny Sergeyevitch Dorn, for it is the latter who encourages more Western and more socially relevant art that young Treplev’s mother despises. It is Dorn who likes the little we see of young Treplev’s play in his innovative outdoor theatre in Act 1, a theatre that requires to be built as a stage within-the-stage of The Sea-Gull itself. He tells Treplev to keep up his writing and to keep aiming for the ideal that ‘a work of art ought to express a great idea’, and to fine because a ‘thing is only fine when it is serious’. He must ‘write only what is important and eternal’. Yet Treplev is flawed by his child-like narcissism. Hearing praise from Dorn before the latter outlines his ideas cited immediately above, he ‘embraces him impulsively’ as if praise alone were the aim of the artist, causing Dorn to say almost as an aside in Treplev’s presence: ‘Fie, what an hysterical fellow! There are tears in his eyes!’. [1]

Treplev chooses the equally young Nina as the actor of his one-person play, a play wherein the one-person is less a person than an ‘abstract idea’, the spirit of all life that once was the sum of all individual animal and human material lives which have passed away from earth in some vast mass extinction. Nina is very young and in Act One (though she grows up before Act IV, unlike Treplev) rather favours following the glitz and glamour of Treplev’s mother, Irina’s, theatre-world of shows and the slight short stories of Trigorin (about whom Treplev says ‘after Tolstoy or Zola you do not care to read Trigorin’) than be ‘united in the effort to realise the same artistic effect’ with Treplev.[2] As she says to Treplev’s disappointment: ‘It is difficult to act in your play. There are no living characters in it’. She tops that by saying that there is ‘very little action’ and ‘nothing but speeches’ therein.[3] It is only after sore disappointment with the theatre that had suited the worldly diva, Irina, and having so developed as an autonomous thinker that she yearns for a greater art, quoting lines from Treplev’s written script in Act IV in a way (as poetic art) she had not understood when enacting them in Act I, though still not finding it in Treplev as an individual, at which point the latter succeeds in his final completed suicide attempt.

Treplev loves Nina, he says in Act I, because she has the supposed freedom of a ‘sea-gull’, ‘drawn to the lake here’. That Treplev answers this by gifting her with a sea-gull killed by him in a shooting exercise on the estate, and which he later keeps in his home (stuffed by a taxidermist), shows perhaps that there is really only a deadness in what Treplev sees as freedom, one from which Nina has to escape into her adult life as serious actor of serious written script. Hence that is why Act IV, which ends with Treplev’s off-stage self-shooting, starts with the reference to the desiccated theatre built in his garden for use in Act I. Of that stage, the schoolmaster, Medvedenko says in Act IV after pointing out Treplev’s increasingly dark nature, like unto a Russian autumn, that the trigger to his earlier artistic ambition ought to be destroyed:

We ought to have told them to break up that stage in the garden. It stands as bare and ugly as a skeleton, and the curtain flaps in the wind. When I passed it yesterday evening, it seemed as though someone were crying in it.

In fact there is someone crying in it. It is Nina, crying like a child for the end of childhood fancies and the coming world of the frustrated adult for whom nothing is clear-cut, who tells Treplev, and us, of that fact later in Act IV. She does this just before Treplev makes his final wooing of her out of his cold and empty hopelessness, like a child for whom if there is not all I desire, there is nothing:

I am alone in the world, warmed by no affection. I am as cold as though I were in a cellar, and everything I write is dry, hard and gloomy.[4]

Dorn, who I think stands for Chekhov – the doctor yearning for a ‘serious’ Russian art, may identify Treplev as a prophetic artist-sage but, if he is, Treplev is a prophet who cries in a vast, cold, Arctic wilderness, whose vastness locks him in as much as if it were a cellar. It is Dorn who finds Treplev dead, lying to his mother that a ‘bottle of ether has exploded’ causes the shot that kills her son. For Irina does love her son, and had they the ability to communicate could have animated his otherwise dead plays, but since they can’t their love-relationship is locked into unspoken Oedipal fantasy.

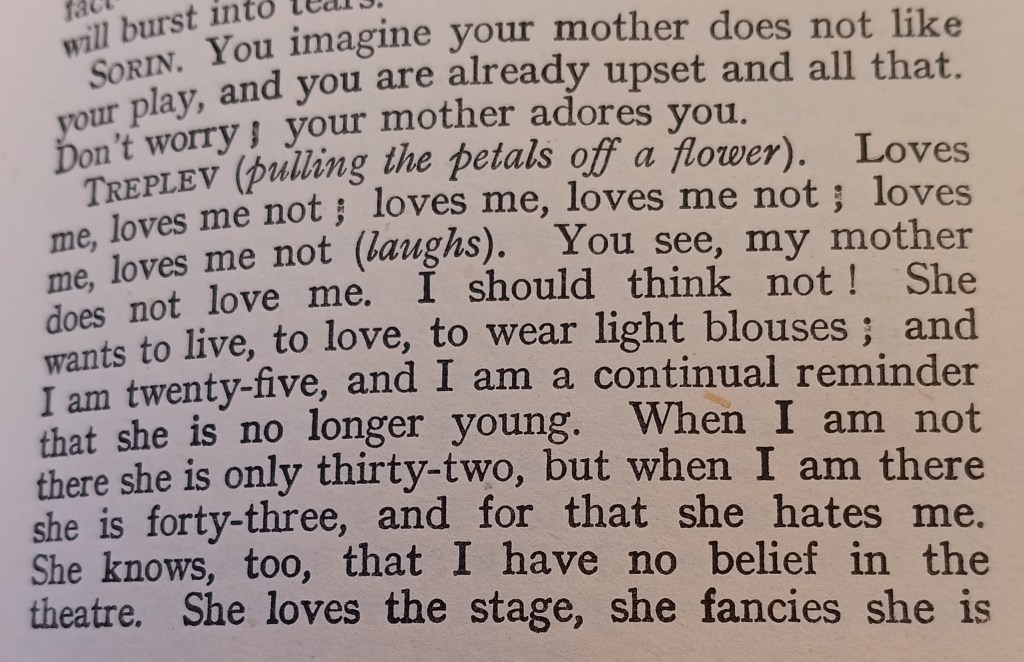

I have delayed long enough looking at the Oedipal heart of the play, its case for a revision of what it means to be a ‘child at heart’; the theme of most great tragedies from Sophocles’ King Oedipus, through those of Shakespeare but especially King Lear and Hamlet (and for Chekhov’s purposes Hamlet in particular). Irina’s frustration at her son’s play-writing and his frustration with her acting is played off in a supposed contention about the role of art in society. Treplev fills us in on this as he pulls the petals from a flowerhead, playing a ‘she loves me / she loves me not’ child’s play:

Anton Tchehov (sic.), translated Constance Garnett ‘The Sea-Gull’ (1950 reprint: Act I, 157f.) in Anton Tchehov, translated Constance Garnett ‘The Cherry Orchard and other plays’ London, Chatto & Windus, 151 – 230.

In this play as Irina waits impatiently and unsympathetically for her, in her view egoistic, son’s play to start in her estate garden, she, like any great actress might, enacts her frustration at Treplev’s request that she be ‘patient’ with a speech from Gertrude, presumably from a famed Stanislavsky Hamlet– the one in which Gertrude shows her fear of her son’s accusation against her as light of fancy and a betrayer of the memory of his dead father (the Oedipal theme of the play in a nutshell in Act 3, Scene 4, lines 99ff. that it did not need the psychoanalyst Ernest Jones to discover):

QUEEN O Hamlet, speak no more!

Thou turn’st my eyes into my very soul,

And there I see such black and grainèd spots

As will not leave their tinct.

To which Treplev replies using Hamlet’s words from earlier in the same scene (lines 42-3):

And let me wring your heart; for so I shall

If it be made of penetrable stuff, ... [5]

A son who uses the metaphors of violence in order to test the value (in terms of the genuine amount of soft heart in his mother’s supposed hard bosom) is precisely how the conduct of the themes of the role of art is played out in this play – in a dynamic locked in infantile tensions, not to to be resolved in the play for, if anything, by Act IV, Treplev has become even more sensually besotted, and less ambivalent, with his mother.

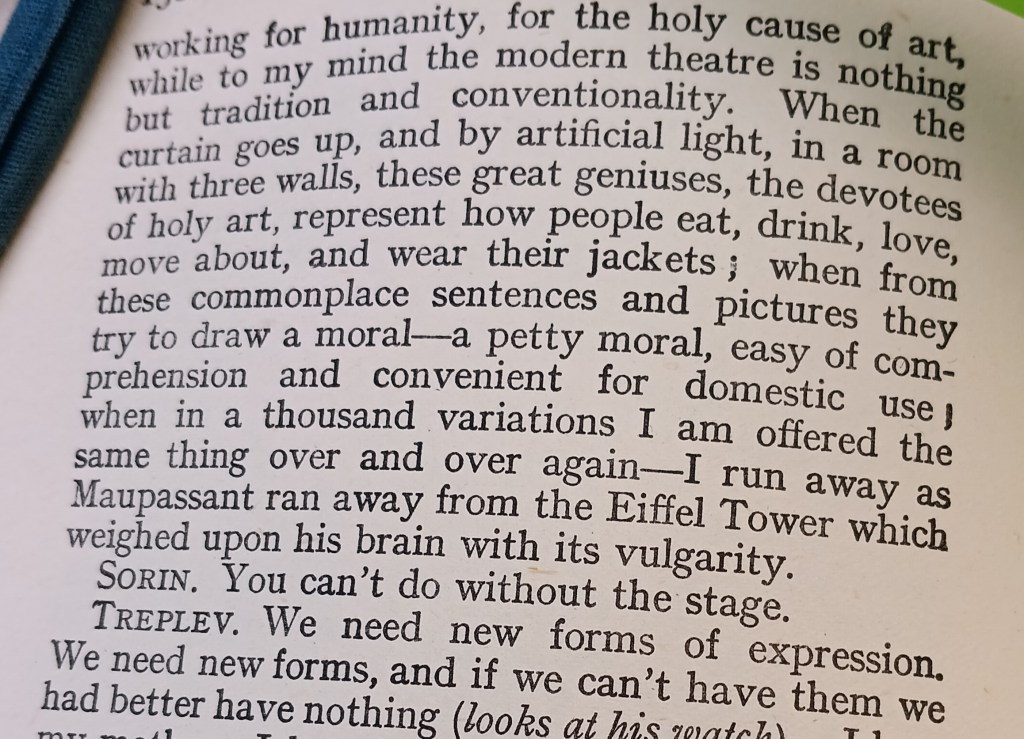

Treplev, like Hamlet (Junior), thinks the time ate ‘out of joint’ and that he has a duty ‘to set them.right’ but not as military prince, as in Shakespeare’s play but a proponent of ‘new forms of expression’ in art and an awareness of human antagonism to the natural world and the natural life in it. To him, the very opposite of what is natural us the refined, and in his eyes artificial, manners of his mother, which though capable of sublime forms of expression have no human heart in them.

Madame Treplev, Irina, if well played (a test to apply to Quentin’s range as an actor), does have that heart but finds it unrefined to demonstrate that. That is the tragedy of this play that underlies its social comedy. Yet we are never allowed to see how Irina reacts to her son’s suicide, for that fact is kept from her at the denouement of the play. The inference is clear. No one wants to see the ‘natural’ emotion of an actor, such as her respo se to mortality against which she is heavily psychologically defended, a lesson about female actors that Nina too learns, but too late.

The only time we see Irina vulnerable is in her fear of losing the younger-than-her, Trigorin, to an even younger female actors not yet matured, Nina in Act III.

Am I so old and ugly that you don’t mind talking of other women ro me? (puts her arms round him and kisses him) Oh, you are mad! My wonderful, splendid darling. … You are the last page of my life! (falls on her knees) …. I shall go mad, my marvellous magnificent one, my master … [6]

It is impossible to judge the validity of the other-focused emotion so full is it of narcissism, the very narcissism Irina sees in her son’s. The content of the emotion is all about her own prescripted stagey emotionality, the fine writing given to a female actor to read on stage bit without the sense of what it might mean for all life to be lost to human artifice which Treplev gives to Nina to read in Act I, and which she recites from memory again in Act IV, some years later in the fictional of the play’s time duration. Irina is possibly the most tragic character in drama – a woman who is never allowed to write her own script in life, not even its ‘last page’ and, unlike Lear and Oedipus, never given the chance of facing down the effects of mortality other than those evaluated by the male gaze.

Why then revive this play? I think it might apply to the themes of nationhood that Chekhov applies to Tsarist Russia, but this time to a Scotland in like existential crisis, torn between imported English culture and the birthing of a Scottish tradition for the Scottish people. Let’s see in which way Poulton and the director make the play Scottish other than in linguistic ways, But it matters too in Edinburgh because the very existence of the International Festival annually there continually raises the issue of whether a democratic national culture for Scotland itself is ever represented. It would not be beyond credi elite to see Treplev demanding such new forms of artistic expression, not dependent on imported English talent.

But even if none of this occurs, I think the play raises the question of what growth and development means and the cost, as well as benefits, of these things. Treplev dies an underdeveloped and overwhelmed child, Nina lives to bear maturity and maintain the radicalise that Treplev could write about but not ‘live’. He remains immature, whilst Nina grows up into a freedom that must be endured and not only enjoyed, as adult life truly is that is not factitious.

That is a lesson we require in the twenty-first century more than ever. Note, however, that Chekhov gets suicidal completers quite wrong in this play, if not in later ones. They are not emotionally limited cognitive children like Treplev, but in my experience of work in the area, people whose resources feel they have run out for good reason, not least a world that saves its resources for the few not the many. That is the real weakness of this otherwise great play.

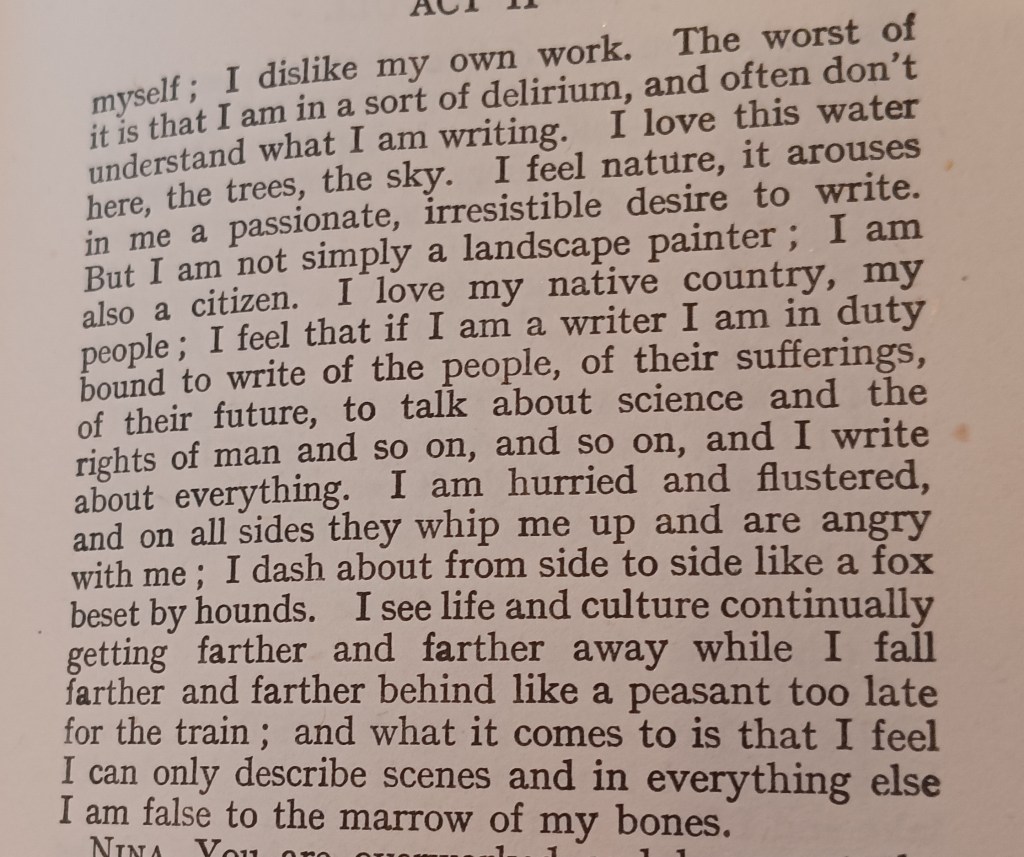

For Treplev’s true message is understood by the writer, of plays as well as novels and short stories like Chekhov, Trigorin. Trigorin dislikes ‘his own work’. For him, it fails to find ways or ‘forms’ in Treplev’s word, to express the best of nature and humanity because it is so self-absotbed in the world of the status quo maintained as such by power and vanity. His speech is a good place to stop, for it alone justifies the revival of Chekhovs great soul submerged under such love of social appearances:

Anton Tchehov (sic.), translated Constance Garnett ‘The Sea-Gull’ (1950 reprint: Act II, 189.) in Anton Tchehov, translated Constance Garnett ‘The Cherry Orchard and other plays’ London, Chatto & Windus, 151 – 230.

This play should not make us hanker for childhood innocence, but to recognise that childhood is a time in which we build the defences that childhood exposes us to – the overwhelming emotion of our vulnerability in a world of adult abuses. And many of us over-build these defences – people like Irina, who is more like many of us than we like to admit- and thus fail to grow into serious life, staying torn between the binary of tragedy and comedy, whilst true mature life is tragi-comic, like Shakespeare’s late ‘problem’ plays as well as the inimitable Chekhov.

I will report back from Edinburgh. Bye for now.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[0] The text I use in this blog is Anton Tchehov (sic.), translated Constance Garnett The Sea-Gull (1950 reprint: Act IV, 211f, & Act 1, 189 respectively) in Anton Tchehov, translated Constance Garnett The Cherry Orchard and other plays London, Chatto & Windus, 151 – 230. The text used at the Lyceum is a more modern adapted version with Scottish linguistic additions by Mike Poulton ( I can’t get a copy).

[1] Ibid: Act 1, 172

[2] Ibid: Act I, 154

[3] Ibis: Act 1, 162

[4] Ibid: Act IV, 225f.

[5] the text is quoted – with slight but possibly important differences of punctuation in ibid: Act I, 164

[6] ibid: Act III, 203.

One thought on “Innocence is not the condition of childhood- rather it is inability to control the heart or stop it from being overwhelmed. This blog is an attempt to prepare myself to see a revival of Chekhov’s ‘The Seagull’ at The Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh on Wednesday 29th October at 2.30 p.m.”