October 21st 2025: The first day of my birthday treats ends earlier than planned: Mea Culpa!

I started this blog on the 21st October and its now the 24th and so backlogged with diary like blog reports. However, it helps to organise my brain to do them. On the 21st, I wrote this after an earlier return home than expected. Lately, I said that, in the end, I decided to add the play Punch to my birthday treats (see the reasons at this linked blog).

If you had read the version on the 20th October of my blog on Punch, you would’ve seen that the new visit planned (to James Graham’s play Punch at the Apollo Theatre) was to be tonight, the 21st – but lo and behold, after dinner we got to the Apollo theatre on Shaftesbury Avenue to find I had mistakenly booked it for tomorrow night (the 22nd). Dinner, by the way, was at Charing Cross Road had been rushed unnecessarily. It was at the Marahraja, 19a Charing Cross Road. Here we are with our lovely host, Najeem, who took the picture. He was a wonderful waiter but is also a computer engineering student.

I have amended the Punch blog now to read as the true one should be – as it is now below also:

| Tuesday 21st October | Wednesday 22nd October |

| 10.30 a.m. Lee Miller’s Surrealist Photography at Tate Britain, Millbank: Followed by river boat to | 10.30 a.m. Gilbert and George retrospective at the Hayward Gallery, Southbank |

| 2.00 p.m. Theatre Picasso at Tate Modern | 2.30 p.m. The Bacchae A new play by Nima Taleghani after Euripides, The National Theatre. 7.30 p.m. Punch Play by James Graham, Apollo Theatre |

So the 21st October ended early with a walk down Whitehall and an 87 bus to Horseferry Road, and a walk across Lambeth Bridge, where my photos in my opening collage were taken of the upriver view. At the southbank end of Lambeth Bridge, you get The Houses of Parliament in the view. We were back in time for Bake Off (oh, the irony! I hate bourgeois TV competitions).

So this was today – mainly in pictures. We started with a walk over Lambeth Bridge and on Millbank to Tate Britain to the Lee Miller exhibition previewed at this link.

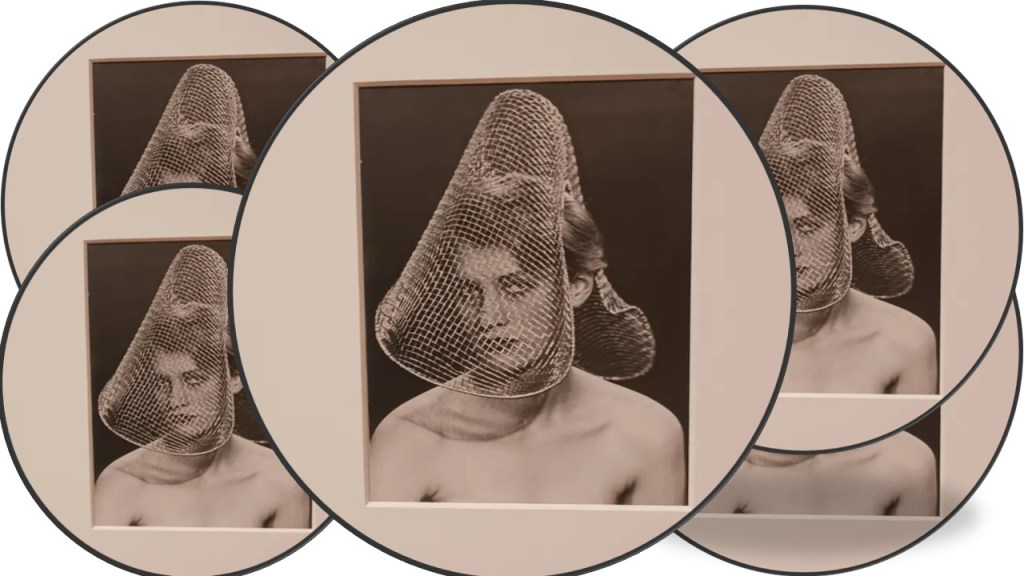

I thought that the only way of recording it was a collage picture show with a comment on themes that mattered to me. So let start with the problem the critics raised: basically that the sizing and grouping of photography as a medium is intrinsically, to use the most reductive term but the one definitely implied: ‘boring’. That replicates the feeling I can get in photograph exhibitions sometimes that the the exhibits are better seen at leisure in a book since, after all, the term reproduction is nearer to what photography is than the implications of the word ‘original’ as , say, Picasso might have used that latter word. And, try as you might, it is difficult to show how the experience of looking at wall mounted photographs actually constitutes an experience akin to that we associate with responses to art. See what I mean:

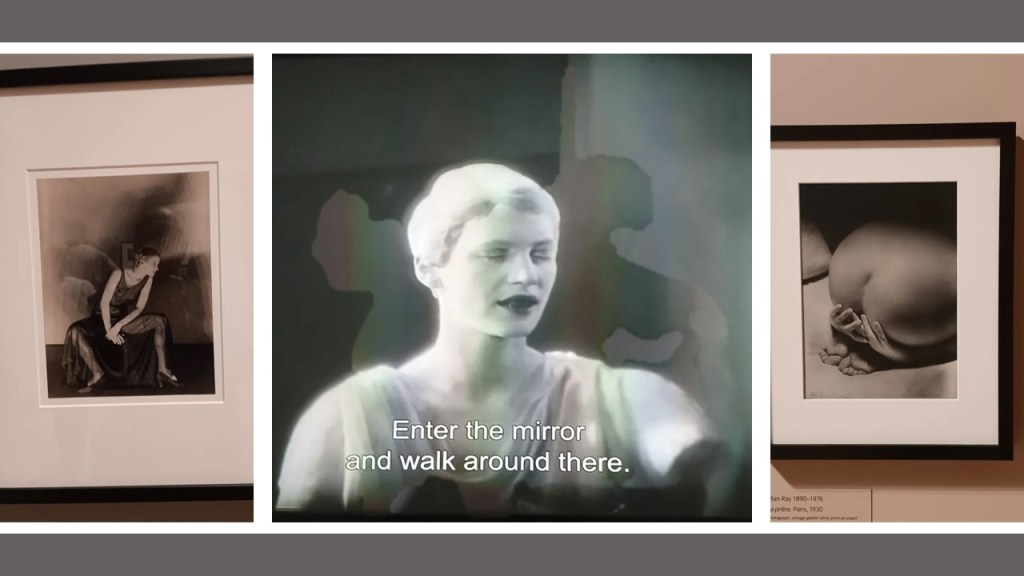

I think however I was right to guess in my earlier blog that the rhythmic frequencies of the themed display does have its own excitement in good photographic display and, indeed, that, on reflection after seeing it, we had this here. If anything I hope my collages will show this. The first themes however were autobiographical. Lee’s career is oft traced back to her father who, from an early age, for Lee, used her as a model, although (to his credit) he also taught her about making photographs. Nevertheless, it was as a model that she became to be known first and as a model chosen by the best photographic artists, who promoted her within their circle, not least Steichen. It was Man Ray she aspired to, however, who looked to use the nature of the photographic process, as well as the use of mise en scene (and unusual points of view) to enhance the ‘surrealism’ of the images he produced. Steichen managed that introduction and many photographs in the early exhibition show how Lee worked with Ray and his circle of surrealists, especially Jean Cocteau working in film, to become part of the surrealist project.

Surrealism was always a movement with contested meanings – sometimes it looked to exploit the quality of being a representation ‘above’ or ‘over’ realism to question the stability of the relationship between things and their given names, or explore their nature of dream-like association to things which destabilised our sense of comfort in naming or describing them. Sometimes it insisted that we need to look squarely at things we thought we knew about and re-know them. At first Man Ray’s images of Lee seem to absorb her into his world – one where he question the meanings of her appearance in the world ,- as a beautiful woman for instanced is reduced to ‘parts’ of herself, and in unusual juxtapositions of those parts, such as that of the hands and anus in the third picture in the collage below, or by projecting onto and into her a shadow world not surely only hers but his but maybe only partly so hers. Just as in the use of moving images of her body as that emergent from the point where a Greek statue of Athena comes to life in Cocteau’s use of her in film makes her still an object of surrealist attention rather than its subject – a product of its metamorphoses of things by revisioning them from within the artistic gaze. Even her words make her a ‘portal’ (‘Enter the mirror and walk around there’) to their (not her) surrealist project. But to see that piece of film also shows that Ray’s and Cocteau’s view of Lee made her the object of enchantment not the producer of it as an independent female vision:

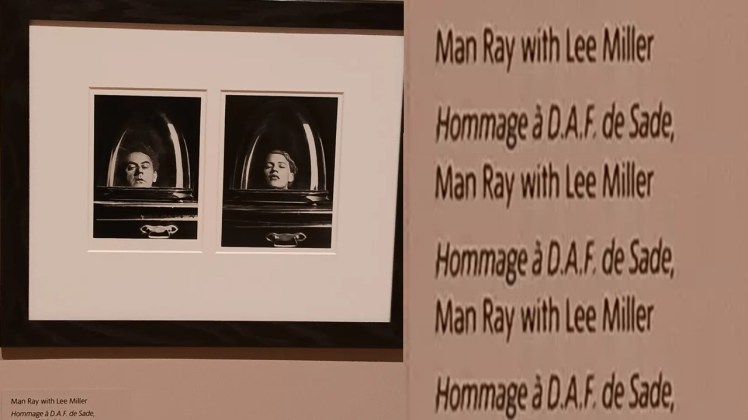

In fact, even when she is attributed as co-artist, although the word ‘with’ in that attribution hardly shows equality, she seems objectified, though no more than Man Ray is also, in a Sadeian vision of fragmentation of the body into collectible fragments, where the making agency, even down to de Sade, is male.

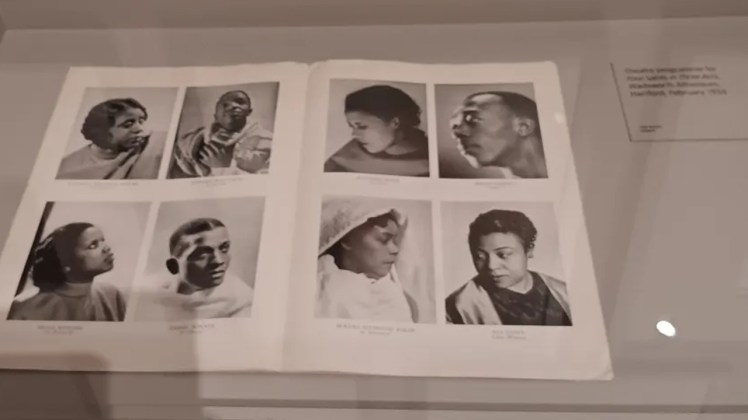

I don’t sense the same degree of subjugation where Lee becomes part of surrealist team work headed by a female vision as in her photographs for Gertrude Stein’s work, with Cocteau and others, where the othering of women and Black people are explored together, partly perhaps as a feedback from Stein’s dynamism:

When Miller becomes not only the object and subject of her art because she is also its maker; her surrealism has a kind of strongly feminist angle that is not only theoretical, as it sometimes seems with Ray. Below Miller shoots herself – yes as a part of the whole woman, but so reconfigured by being matched with that favoured object of hers, a fence-guard, that the whole picture acquires meanings that nuance the notion of the feminine by offering very complicated interpretations of its match with the beauty of her face – beauty with defensiveness, perhaps even ‘on guard’ offensiveness.

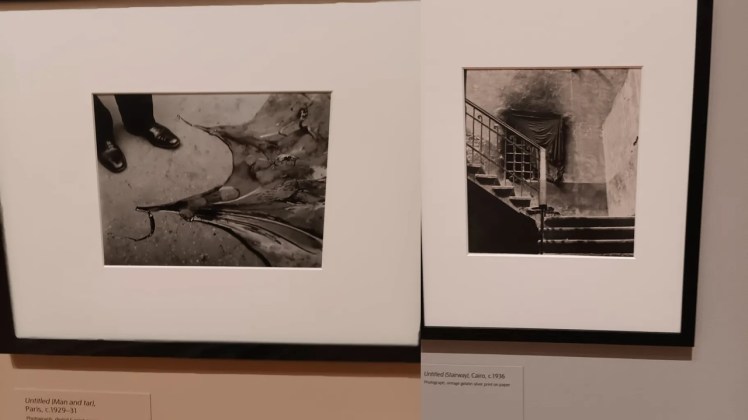

And, freed from the shackles of an authoritative mentor, Miller explore the photographic process itself – learning as the images below do from Atget’s Paris pictures, and manipulating not only the direction of view but also replicating it with a difference. Here the work questions if the objective world were not more than the solid reliable ironwork of the crafters but a product of the vision of the shifting agency of light and shadow, and the association of solid objects and spaces with other more subjectively fuzzy entities.

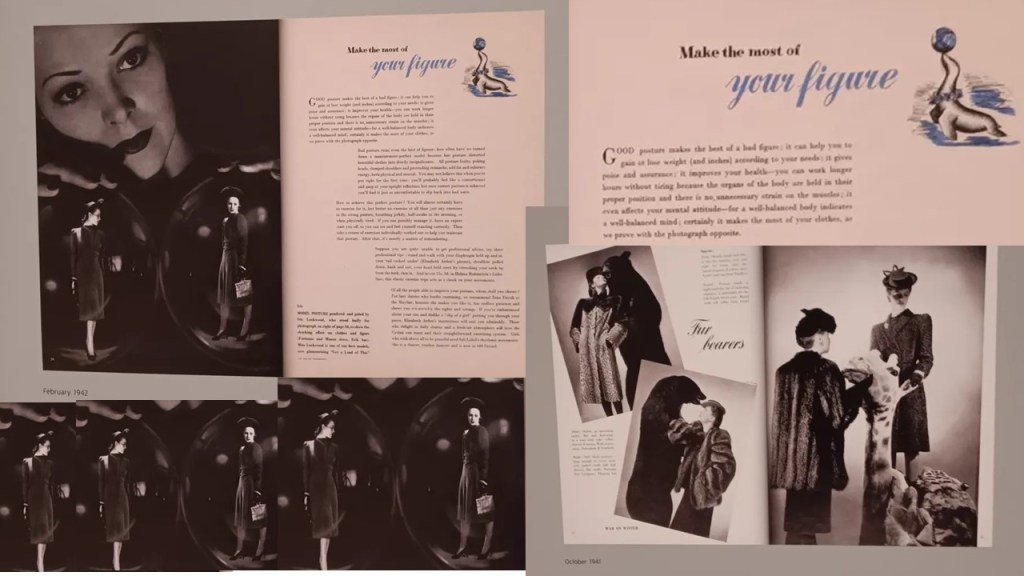

And there may be in that something that shows that Lee wanted to undermine even the most cosy of worlds, such as those of the dilettante aiming at manipulating images for the purpose of personal beauty or attraction, but in doing so, showing a more vicious reality underneath it – like the world of animal torture underlying haute couture in furs or the self-objectification in which women become complicit in colluding with the commodification of fashion (like being placed withing a huge scientific glass apparatus to be observed and boiled down by a superior being). Lee’s attitude in all this is highly nuanced. She produces beauty to please Vogue and its readers, while undermining that world if you are prepared to see that the reality of the world of fashion, also shows us so much more about what is over and beyond the supposed real world:

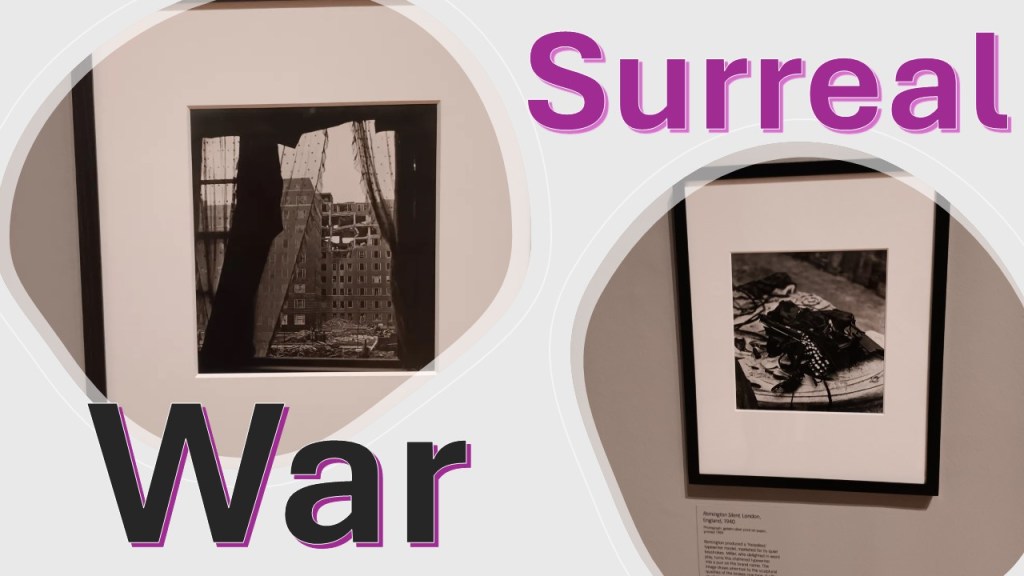

And when she becomes a war reporter, there is a sense that what she views in war is that the world itself has no need of surrealism – it produces strange combinations of ideas unaided by ought but the absurdity of competing drives to render the world your own and known as you want it to be know – the beauty of that picture Remington Silent (her own typewriter was a Remington), where reportage is broken by destruction of that which reportage once tried to describe – the very characters of the typewriter mangled.

Suddenly, a window space becomes compromised when its frame is shattered.

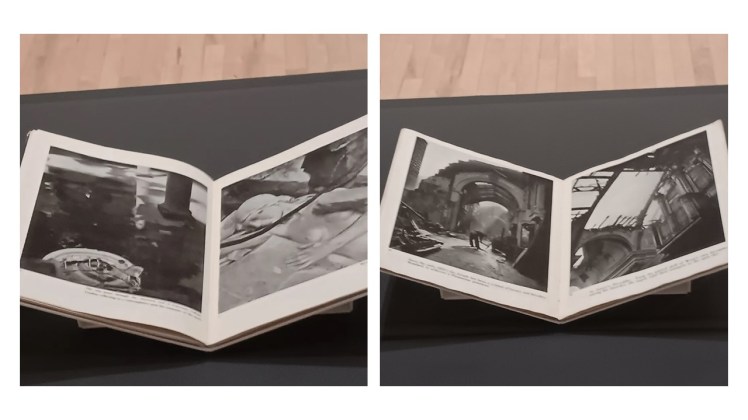

In the room named after her book, Grim Glory of which as I said in my last blog I have a first edition at home, there is something even spooky in seeing copies of that book at certain openings in a vitrine placed centrally in the room:

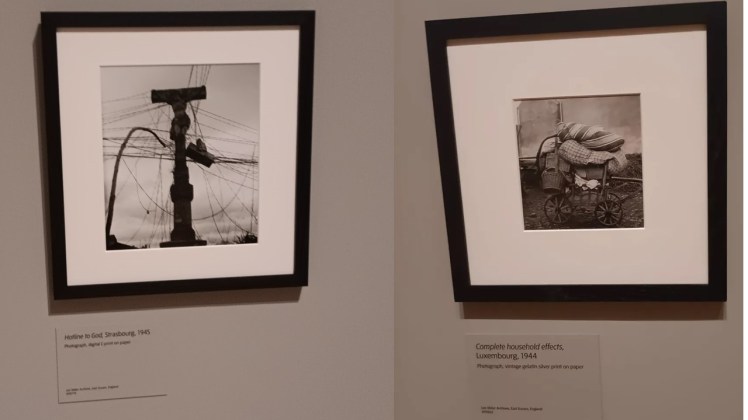

And then every aspect of war queers the world we want to find norms within, as in these wondrous images that unpick the world of supposedly direct communication and transmission of personal messages, or what a home is once piled onto a vehicle so that it too is migrant.

Yet the performative can be a means of performing an unsettling stillness, as in the cubist portrait below.

And in the middle of a room with such images is a figure – a tailor’s figure – dressed as Miller as war reporter. I have flanked her by her pictures of, respectively:

- A pile of what she called ‘starved bodies’ that the camp commandants had not time or fuel to burn before Allied troops enter the concentration camps, and;

- A camp commandant just after his suicide in a room outside which beautiful statues representing the Reich he followed and can be seen through the window. This gets under the skin of the ‘real’

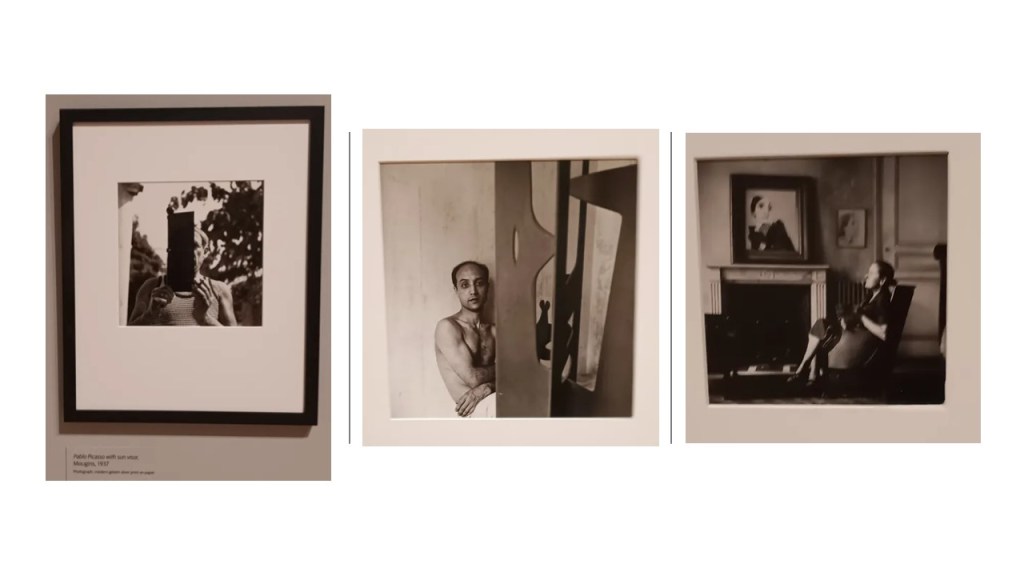

We moved on from those final images with some difficulty in reconciling ourselves to a world offered for enjoyment. But let’s remember that, even when artists or models stand by art that represents them – the photographer KNOWS the world, even of art-making is as queer as the art itself – be it Picasso, Dora Maar – artist and model – or a sculptor reconfigured into that sculpture:

We chased over the road however to find a boat waiting for us to travel to Bankside Wharf, outside the Globe Theatre. We glanced at The London Eye of course, which failed to look back at us:

With time to spare before our tickets were operative for the Picasso exhibition, we wandered around Borough Market. But as I looked at the evidential photographs, I noticed that even the most unskilled of photographer (myself) cannot help but capture through a photograph what makes the known world feel unknow. below the scene of the river ahead on the boat carries reflections on the surface of glass and metals that change the spatial scene and so reconfigure it, that anything can seem not quite itself but a world of images alone, and even the light on the curvature of Borough market curved ceilings have an estranged appearance.

To step, after coffee and croissant, into Tate Modern’s new Picasso exhibition is to step into a deliberately remodelled environment that aims to use its approximations of what the theatrical might be as our only access to those favoured representations of the world and things in it we like to call the ‘real’.

As a result, anything we see in the Theatre Picasso exhibition has to be put into the visual context of theatre, without being in a theatre at all, for theatre is also a metaphor for any display or performance. That basic metaphor of what all representation is – that is, it is ‘performance’ – has to be created in very obviously faked theatre scenes featuring the backs of scenic flats, the display furniture of the archives of great collections, prosceniums and faked art gallery walls. I took some pictures of that aspect of the show that appear in the collage below. These pictures may register my feeling that all of this is far too obviously the equivalent of a rather over-enlarged childhood theatre toy. This aspect of the show felt rather tedious to me after the first instance of it has been seen, such as the two levels of the gallery joined by a ramp corridor which divide the visitors to the exhibition into a participant of the spectacle of the show and the viewer of that spectacle in which they now realise they have taken part.

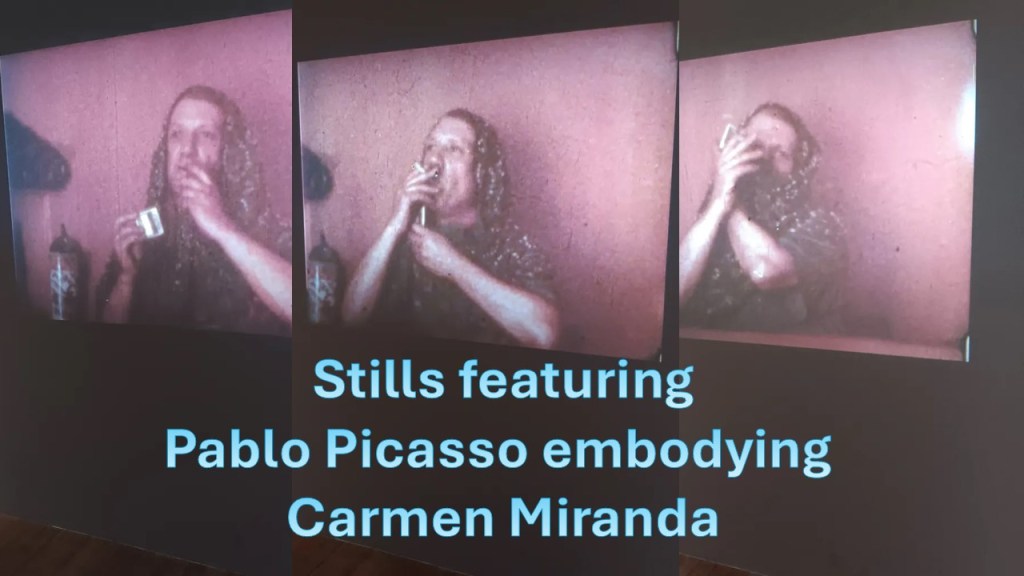

Within this context, we are to be persuaded that Picasso paintings and drawings are both reflexive showings of the process of making visual art and celebrations of the performative in every aspect of that which we call life and its representation. This is what remains to me from the exhibition, but I do not think the forceful effect they had in me owed a lot or anything to the makeshift nature of the institutional theatricalised and display contexts of the curation. If anything, it over-emphasised the viewers (see the collage above again) and had the effect not of making them participants but of dulling down the imaginative processes (and these are not elitist as people sometimes imagine – they just require a certain attention of the gaze so the stillness may speak and move as making processes are recovered by the viewer) required to see the dynamism of Picasso’s art. There are many points, very intelligently made, about the idea of what the performative is in the curators’ words in the catalogue – few of these however were really animated by the art of the curation as I had hoped – except for the blindingly obvious – in the showing of films of Picasso in self-performance, as a drawing artist (the inevitable wonderful film Mystery of Picasso – I have a DVD at home – which at the exhibition was animated before an audience setting of tiered benches) or, below, in stills with Picasso at play as Carmen Miranda – an excerpt shown on entry to the exhibition:

But otherwise, what was the point of hanging the prints – wonderful as they are on the metal grids of the drawers used to store paintings little exhibited but requiring display on request – oft the fate of drawings. Such animation as they possess is not in that retrieval process but in the animative effect of the movement of lines caused by the saccading gaze (the random sizing movements of the pupil of the eye directing the gaze) of a viewer, or so I felt anyway. It is the latter that moves the tongues in the kiss so brilliantly performed below, so that an animated gaze incorporates the haptic feel of the tongue, feeling the intrusion of the beard on it and the smell evoked by the dance of nostrils together. In looking at that wonderful drawing on the right of the collage below., does the archival hanging board help makes these courtesans feel each others flesh though even symbolic contact, involving moving gesture of body, including hands.

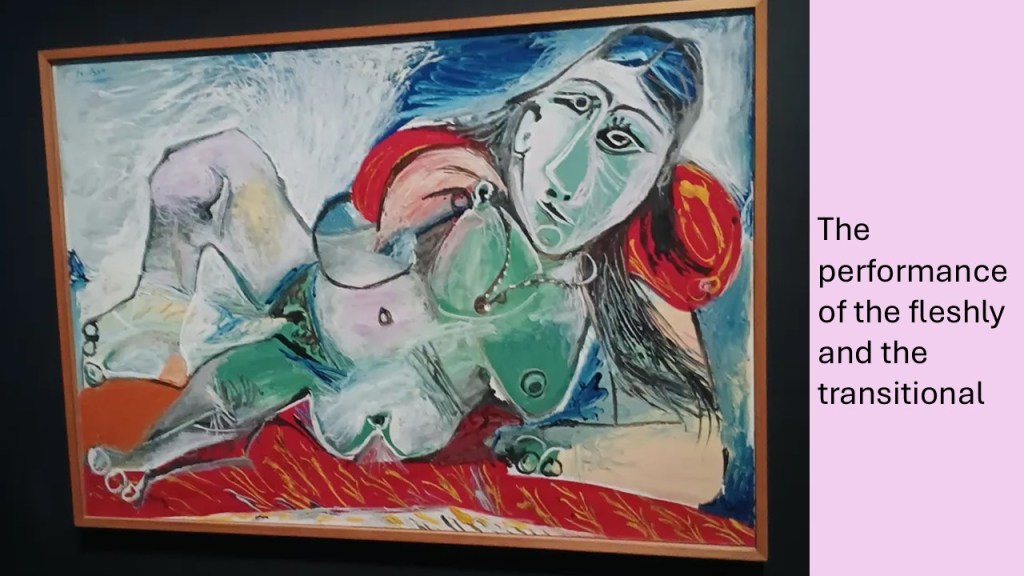

When Picasso line is truly animated, it performs the making of object – often the phallus or vagina to appear uncertainly amongst its tangles and fleshly interaction. The drawing below animates the sexual act s involved completely in that fashion and others, where faces too and feet shift position or their perspective on each other’s bodies by virtue of the viewer’s performative gaze in making sense (in the sense of sensation too) of the couplings, layerings, and interactive shapings.

A similar deregulation of parts, if less radical, is found too in the oil painting below, where the restless shifting of body parts underlie the still gaze of the courtesan upon the viewer, and renders even more pressing the sexualised animation of the golden shower from the figure’s vagina. However, the painting is not only on the cusp of stillness and motion but stable imaging set against imaging in constant transition, to which I attribute here the masculinity of the painted hands as if they were the provoked enacted embodiment of Picasso’s hands making the body of his figure round out from the painted surface.

But of course The Three Dancers remains the performance that stars in the show, in which dynamism and flow are made more apparent by the eyes working their effects of sensing its basic shapes by constant movement, that gets transferred to the figures, set as they are against inner frames which they escape too. But putting it on a literal fake stage helped not a bit in helping us understand how painters become performative in their making.

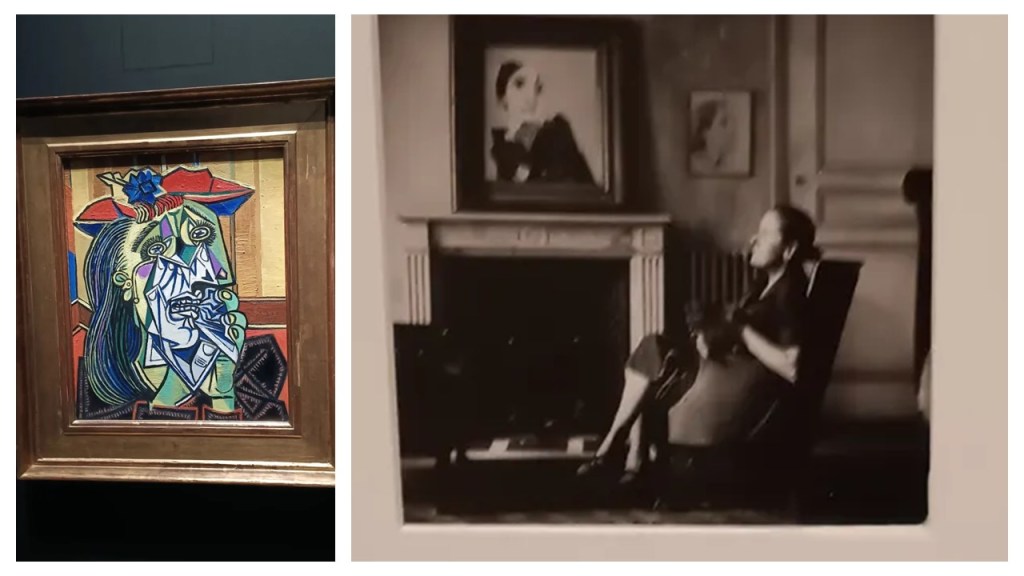

Strangely enough, Lee Miller’s photograph of Dora Maar sitting with one of Picasso’s other portraits of Dora seemed relevant to me here. It would be more so if the portrait been The Weeping Woman (left in the collage), for her stillness with only semi-gaze on her alter ego would show the picture’s independent restlessness and dynamism.

It is not only the rolling of tears but the endless constructive/ destructive motion of the hands that have either not yet filled in Dora’s mid-face or torn, erased the skin / paint from it. These hands are commonly recognised as those of Pablo rather than Dora.

Seen thus every ‘style’ in which Picasso chose to mount performative art, however different their technique, method and rationale, always used those large hands of the maker that serve often to gender-queer the subject of the painting. Take the one below in his ‘classical ‘ style.

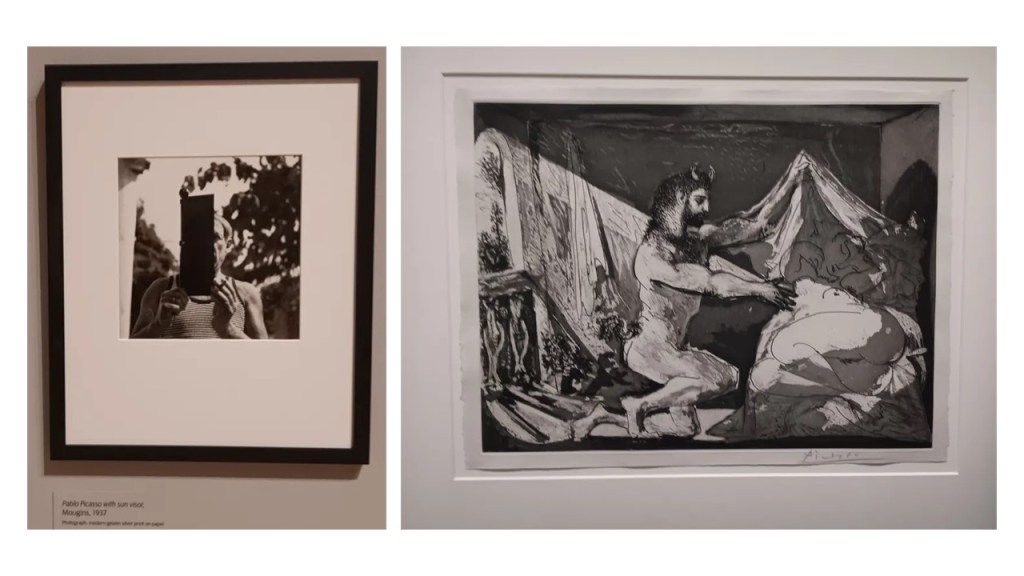

That point seems also to be hinted at in a Lee Miller photograph of Picasso, where he uses his hands to manipulate access to his face by using a sun-screen to semi-obscure it. It ‘reflects’ the way in which the classical drawing I have collaged with it plays with desired reflection of male and female figures. The overly athletic minotaur-bull-man, the very opposite of Picasso’s own figure as a man, pulls apart the veils covering over the female figure he desires but sketches in so lightly. Are the curators right then to suggest that their recovered extract of Picasso playing Carmen Miranda makes clear his view of the performative nature of sex/gender in art.

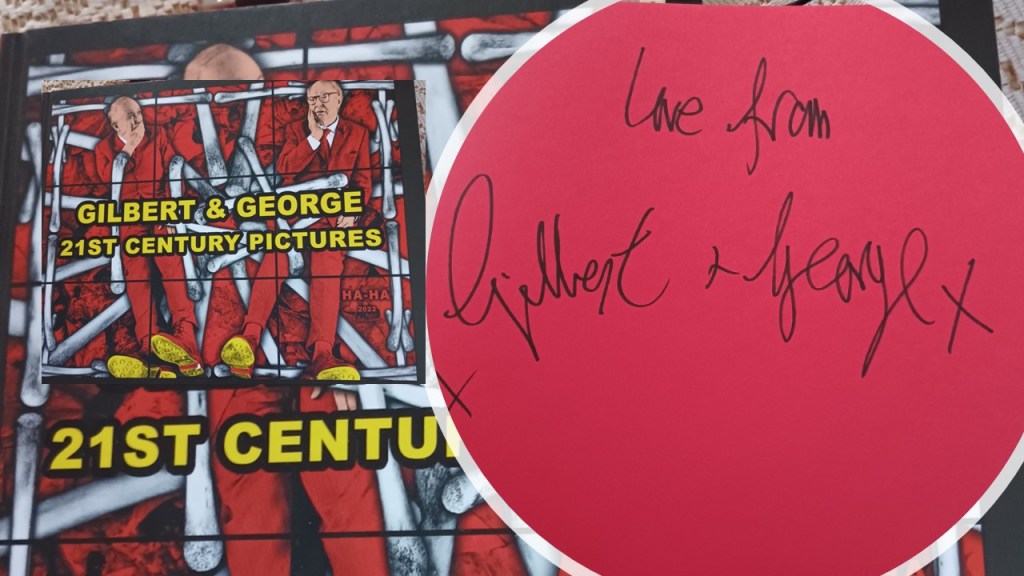

At this point, Geoff and I can now safely leave the exhibition – disappointed in the hubris of its curation, whilst still aware of the subtle re-seeing of Picasso’s art it intended and went a little way to uncover. We plodded home along the Southbank until cutting back to our hotel over Lambeth Palace Park. But before this, we nipped into the Hayward Gallery to buy a copy of the weighty catalogue for the Gilbert and George exhibition that we were to see the next day. I am glad we did because only a few of the signed copies were left.

The rest of the day, I started this blog with writing about. However, I also realised that in making the mistake I did (booking Punch for the Wednesday, not Tuesday night. We were meant to see friend Claire for dinner on Wednesday. Now I had to ring and cancel. In trying to do so I improved tomorrow’s events because Claire determined to join us for the whole day, meeting up with us at 10.15 at the Hayward. And thus it was. But that is a story for the two blogs on tomorrow’s events – the one on Gilbert and George being stand-alone and only written when I have fully read the catalogue, which I have not to this point even started. But here’s Claire. Love her. X

So that was all for that day. See you again.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxx

2 thoughts on “October 21st 2025: The first day of my birthday treats ends earlier than planned: Mea Culpa!”