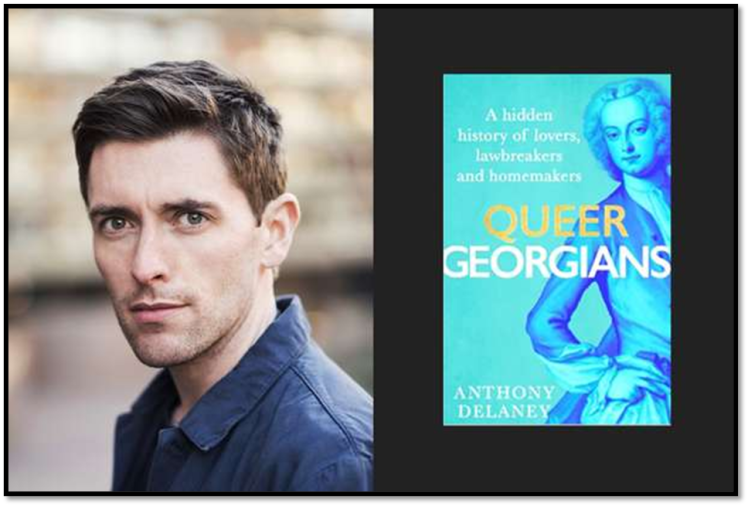

Anthony Delaney’s ‘Queer Georgians’: queer tales from history ambitiously takes Foucault to task for the misrepresentation and cancellation of queer history and charms with the author’s personality at the same time.

If you had to give a prize for the readability of queer history, this book would have to take it. Moreover, it does not sacrifice ambition in the favour of readability with its epilogue taking a vast sweep at theoretical innovations in the writing of history of Michel Foucault, though I can’t help feeling it does so at the cost of over-easy misrepresentation of the Foucauldian perspective on history. He says that ‘Foucault’s theory is no more than a clever exercise in semantics and offers very little in the way of meaningful insight or analysis’.[1] That’s bold and like all self-centred boldness rather wrong-headed, since Foucault’s ‘theory’ was never simply a ‘theorisation’ of what sexual identity might be but a different way of doing ‘history’ queerly rather than looking backwards in the long duration for evidence of ‘contemporary’ constructs – and homosexuality, in the birthing of the term for that construct, was such a construct tied firmly to the history of medical pathology not a framework for a category of person with ontological solidity throughout history.

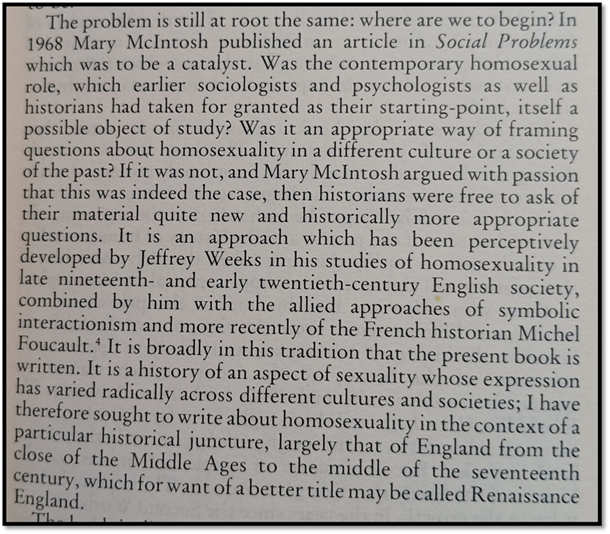

So I want to remember another early queer historian, Alan Bray (Geoff and I once stayed in his Brighton flat – and he was a hero of the Gay Activists Alliance movement, lost so sadly to the period in which AIDS and failure to address it took him amongst its victims). He put Foucault in context thus in his groundbreaking Homosexuality and Renaissance England, without any attempt to put himself into the ring of competing historiographies or reference, but rather to seek truths that were themselves not based on fetishised social identities but instead creating an understanding how such social identities emerged in their particular form, regardless of the label, or multiple labels they were given by hegemonic discourses and / or discourses subversive of that historical hegemony:[2]

In truth what Delaney actually does in his book fits exactly the paradigm set out by Bray, and it might have been wise to slant his frameworking of the argument thus rather than looking for continuities that are specifically ‘homosexual’. Perhaps then the idea of queer Georgian, which homes a diversity of articulations of what was considered queer, including in its negotiations with what he calls the heteroregulated world. Delaney instead puts himself in that ring of individual heroes, and in his own right rather than in standing on the shoulders of other queer thinkers. He does so, ‘having spent more than five years in various archives in Europe and America’: that’s a rather narcissistic qualification and no more than any PhD student, as he was – he was researching the concept of the ‘cotquean’ which is original – does.[3] But, despite that embarrassing self-reference, this book is valuable in that it’s personal and personable, allowing Delaney to share his justified liking for the early homemaking of John Hervey (whilst understanding why Pope lampoons him so homophobically as ‘Sporus’ in The Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot) and distaste for lifelong ‘bad gays’ like William Beckford. He also has a modified but equally justified distaste for Anne Lister and the pinkwashing of positive image-making offered to her by Suranne Jones and screenwriter Sally Wainwright (see them below filming at Shibden Hall in Halifax) in their popular series Gentleman Jack.

Now Bray rather than Foucault, whilst nevertheless working intelligently within a Foucauldian paradigm, did, in a final chapter of his book, initiate the interest in the construct of the ‘molly’, which bloomed massively thereafter in both queer academic and popular cultural takes, that ought perhaps have been acknowledged by Delaney – but young men, even queer ones, are rarely that generous to the young men of the past, except in that it mirrors their ideas. Bray’s take on the historical construction of the ’molly’ in eighteenth-century England does honour that concept as bearing something much more than the ubiquitous use of ‘bugger’ and ‘sodomite’ in Renaissance England and ‘more like the terms that were to come after’ in referring to a ‘social identity’. [4] This is the very idea Delaney amplifies in his key concerns of ‘home’, ‘marriage’ and ‘community’ in describing queer Georgians. Nevertheless like Delaney, Bray testifies to the co-existence of the ‘molly’ term with the older ones. Delaney points to William Beckford’s ideal of an erotic home-place for ‘buggers’ and beautifully described it (itself not unlike that in Lytton Strachey’s terminology for this matter in the twentieth century or Bray’s view of the seventeenth century rake, Lord Rochester, the author of Sodom). I still think Bray’s summary incontestable that ‘there is no linear history of homosexuality to be written at all, any more than there is of ‘the family’ or indeed of sexuality itself. These things take their meaning from the varying societies which gave them form; if they change it is because these societies have changed’.[5]

But in gauging the pleasure of Delaney’s book and its commitment to the groups in the molly houses, and individuals who achieved a kind of self-assertion, particularly the sex/genderqueer persons, we should not let these matters of aggressive historiographical theory worry us too much. I see them as signs of the hubris of the young good-looking not-yet tenured academic in our terrible culture of the academy. They are not as central to the book’s purpose as the author thinks they are. However, his epilogue is fascinating and the picking out there of the themes of the book you will have just read to get there is extraordinarily illuminating about the diverse constructions of queer lives, and some of the nuanced commonalities between these very different lives.

Let’s though beware the subtitle of the book: ‘Queer Georgians: A hidden history of lovers, lawbreakers and homemakers’. We need to beware because the sources of that history are not hidden, they are just accessible from dusty archives in which hitherto no-one has taken enough interest. No-one decided to ‘hide’ them and the force of the word ‘hidden’ is not really of a person uncovering suppressed material as in being the only one interested in read and interpret some, on the face of it, very unprepossessing archives in the first place. Again historians sometimes like to boast they have discovered the previously unknow – instead they have just lit up a subject by reading more extensively and deeply in areas others haven’t. This is certainly the case with this book.

But what Delaney does with the material is remarkable and he is right to be pleased with himself. He finds the material but then subjects to close scrutiny as a reader and master of the use of evidence – finding the case that is implied as much as spoken by that evidence in the light of all kinds of appropriate standards of interpretation, such as coded languages of the period. My favourite readings are sometimes not even the ones from neglected dusty archives but by the freshness of interpretation of well known sources like the letters of poet and gentleman Thomas Gray commenting on the menage of John Chute (1701-80) and Francis Whithed (1710-31), who felt able to tell Horace Walpole that he visited the ‘Chuteheds’, as if that marriage of names was a marriage indeed. Just that little references saves a whole barrage of inference about whether Gray was conscious of queer romantic love or not. The Walpole circle spent much empty time in the hospitality of the Chuteheds. The whole group named the two lovers as if ‘a single spousal unit’ in Delaney’s words, and treated them as expected to behave to each other as if in such singleness of devotion. On the 1st April 1751 Walpole wrote to Horace Mann, in the same circle as Gray of Whited’s death and that: ‘Mr Chute … is half distracted, and scarce to be known’.[6]

There is a singularity with which the scant records are read – even when they have been read before, such as the diaries of Anne Lister, which he compares with recently found material from their partner, Ann walker, who turns out not to such an airhead as Lister paints her, but rather an intelligent woman of sensibility. Lister on the other hand comes out clearly in the comparison as someone who barely regarded Ann Walker, wanted her for her estate, was prepared to use her mental state to have her incarcerated to that end and with little or no feeling but for their own enlargement in the mode of most monied gentleman, exploiting the mining wealth of both Halifax estates like any other chauvinistic landowner.

From: https://english.northwestern.edu/about/anne-lister-society/story.html

The most beautiful stories are of those not in the upper classes – such as that of Mother Margaret Clap and the 53 year-old widower Gabriel Lawrence, enjoying the company of other Mollys and their marriage rites, after some rather unmistakable sexually signed touching up on each other’s knees. The story of Mary Jones / Peter Sewally puts the non-binary into play but not (note to Thomas) in twentieth-century terms even if our conclusions about it might drive us away from an understanding of the naturalness of the binary. There is much performative stuff about that person, and other avatars, such as ‘Beefsteak Pete’ that needs understanding in its own terms. For instance, the last name came from the use of a beefsteak cut with a fissure to act as a substitute vagina in order to inveigle men into her care while Pete, or Mary robbed them of their purses. The connection of the non-binary to crime (not only larceny but vagrancy in New York) is not understandable if you see this figure as continuous with manifestations of the non-binary in today’s term – indeed it would be a way of not listening to the witnesses of history in their own terms. It is too easy to assume that the link to crime was solely related to the subaltern nature and criminalisation of marginalised sexualities. But you have to read this story, although even more needs to thought out in that Delaney presents Mary Jones et. al. as a previously unrepresented Black queer person of the period.

When you read the book, ready yourself for its chattiness from the get-go. It starts:

We have no history. The queers I mean. That’s what they say anyway. ….

Anthony’s writing is often like this though in style. It is like the stagey monologue this of a play from the 1990s, where a representative friend of the cast, even this ancient one, steps forward to clear up a myth or two before we start. Just as in the more ‘theoretical’ monologue, it gets it wrong. No-one ever said that, least of all Alan Bray. But I loved the book. It is a book that will grace my queer library, and should yours (or perhaps get you to start one). There is also fine old-fashioned scholarship here – before ‘theory’ messed us all up. Lol.

Bye for now

With love

Steven xxxxxx

[1] Anthony Delaney (2025: 274.) Queer Georgians London, Doubleday, Penguin Random House.

[2] See below this note in the text for passage from Alan Bray (1982: 9) Homosexuality in Renaissance England London, Gay Men’s Press.

[3] Anthony Delaney, op.cit: 273f.

[4] Alan Bray op.cit 103

[5] Ibid: 104

[6] Anthony Delaney op.cit: 104 – 107