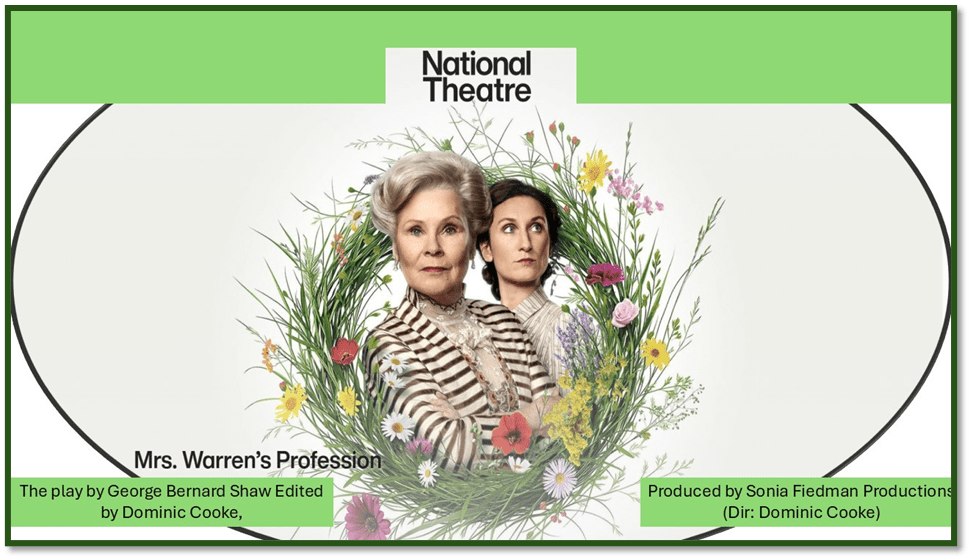

Can ‘principles define how you live’, if you live in the world as it is. This blog looks at this by examining a recent (and edited) play text of George Bernard Shaw’s ‘Mrs Warren’s Profession’, which we see live-streamed on 23rd October at the Gala Theatre Durham.

Geoff and I will be seeing this play (contemporaneous to the live production it is screened from) on the evening of the 23rd October at the Gala Theatre in Durham after travelling from London on my birthday jaunt. I mentioned this in the blog about this jaunt (linked here) where I said we would depart London:

in time for pre-booked tickets for the Durham screening that evening of The National Theatre’s new production of George Bernard Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession. / No doubt the theme of the question [it was ‘What could you do more of?] here may apply to each of these performances / exhibitions, perhaps with the reception of the safe bets around Imelda Staunton in Shaw’s dated social drama about sex and money.

Now that off the hip comment about the Shaw play hides the fact that I haven’t read Shaw since 6th form at Grammar School in the 1960s, where I studied Man and Superman. Previously I had acted in an amateur St. Joan and loved and seen fine productions of Major Barbara, Pygmalion, and just loved them. I have seen Man and Superman done in a good production since where I finally decided that, despite his Fabian socialism and his cerebral quality, I had enough of what I took to be, in Dominic Cooper’s delicious words and theatrical analogy, his characteristic as a:

… garrulous and didactic windbag. ‘Oh, that Bernadette Shaw! What a chatterbox!’ remarks the delightfully camp Captain Terri Dennis in Peter Nichols’ 1977 play Privates on Parade, echoing a sentiment that has been frequently, though less wittily, expressed elsewhere. [1]

Now Cooper rightly takes exception to both the fact Shaw is largely cerebral and a windbag. However, his edition claims to have avoided some of the ways in which Shaw ‘chatterboxes on. Hence he ‘trimmed’ and cut some of what he calls ‘naturalistic detail’, ‘repetition’ , ‘unnecessary exposition’, and, most importantly to him, he:

…clarified and simplified characters’ through-lines. Throughout the play, everyone is struggling to navigate their society’s impossibly harsh judgements regarding sex. I wanted to highlight this dynamic by removing extraneous biographical detail and diversionary wordplay, adhering to the dramatic principle of ‘show, don’t tell’.

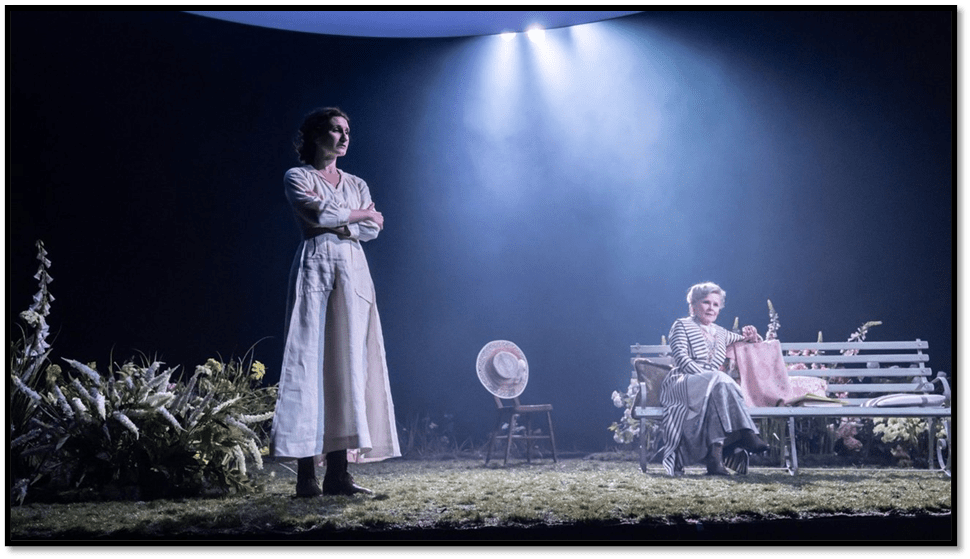

But what he does not and cannot take away, though as a director he may show it a virtue, is that characters often talk at each other as if articulation of what we think, or even feel, mattered more than it does for most of us in our everyday lives. I will need to test out how I feel when I see it done, but there is the photograph below some of the stage markers of what I mean, where a lot is done with facial expression but the bodies of actors are kept separate almost as if to keep a large space for their words that mediate between them in the form of each person setting out their position in a debate on life.

I do not know, but the still above MIGHT relate to this conversation between mother (Mrs Warren, here Imelda Staunton) and daughter Vivie (here played by Staunton’s real daughter, Bessy Carter) to the conversation, from Act II, I excerpt below, wherein Vivie has confronted her mother with the knowledge that she made her fortune as a madam, starting her working life as a prostitute like her ‘girls’ (the language by the way is exactly as in Shaw’s text but for the omission of stage directions – which emphasise that here Mrs Warren returns to a way of speaking from the working class from which she derived:

MRS. WARREN. You! You’ve no heart. Oh, I won’t bear it: I won’t put up with the injustice of it. What right have you to set yourself up above me like this? You boast of what you are to me – to me, who gave you a chance of being what you are. What chance had I? Shame on you for being a bad daughter and a stuck-up prude! VIVIE. Don’t think for a moment I set myself above you in any way. You attacked me with the conventional authority of a mother: I defended myself with the conventional superiority of a respectable woman. Frankly, I am not going to stand any of your nonsense; and I shall not expect you to stand any of mine. I shall always respect your right to your own opinions and your own way of life. MRS. WARREN. My own opinions and my own way of life! Listen to her! Do you think I was brought up like you? Able to pick and choose my own way of life? Do you think I did what I did because I liked it, or thought it right, or wouldn’t rather have gone to college and been a lady if I’d had the chance? VIVIE. Everybody has some choice, Mother. The poorest girl alive may not be able to choose between being Queen of England or Principal of Newnham; but she can choose between rag-picking and flower-selling, according to her taste. People are always blaming circumstances for what they are. I don’t believe in circumstances.

I hope you get my point. It is that it is as if you had asked these characters to talk about the ‘principles by which they define their life’ at a quite high level of ethical debate, where Mrs Warren stresses her rise from the working class by whatever means available to any woman in her ‘circumstances’. Responding actively to one’s circumstances will be one principle here that trumps others, such as the social standards of the class into which she has risen, which to her are the attitudes of those who feel they have a right to act ‘stuck up’ in the company of the morally or materially low in status.

Against this Vivie argues that everyone has a ‘choice’ of moral path whatever their ‘circumstances’, even doubting whether circumstances like income, social status or access to resources matter at all, in ways the play will prove naive. Mrs Warren (let’s call her ‘Kitty’ with the middle class males boys in tje play, whatever their supposed age, do) is almost carrying the weight of Fabian teaching in her outrage about the luxury that the principle of choice meant to the Fabians; when she says: ‘My own opinions and my own way of life! Listen to her! Do you think I was brought up like you?‘, it is almost as if she says to us – how dare you talk about having principles if you have not experienced their negation and impossibility, as she had as a working-class woman.

These arguments win Vivie over until she is told that Kitty is still making a fortune as an international ‘madam’, owning brothels across Europe) – now not because her ‘circumstances’ are poor, or that she needs any longer feed Vivie’s dependency on her for the best in education and life, but because she just chooses to be a ‘working woman’ and that being the director of brothels is the only work she can, as a woman, now do. As the rift between them deepens, it is likely that stage proxemics – the regulation of space between figures on the stage and sets, as well as lighting, will fill the space not just with words, like those above but emotion, as might be more evident below, where bodies do as much work as words in communicating division and connection in ‘principle’

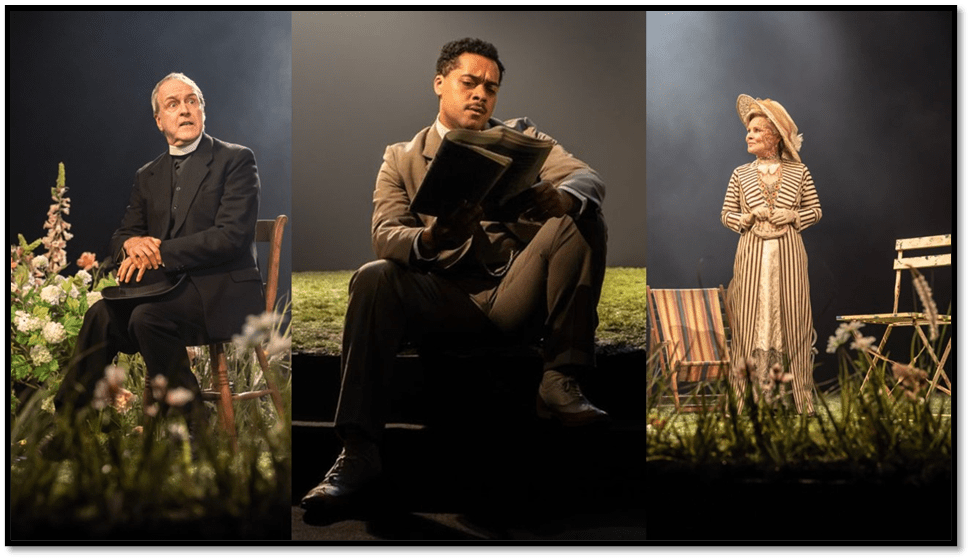

And then there are the Shavian characters, which show us whatever the meaning of Shaw’s socialism, it was boundaried within the choices of middle-class or higher status people, like Jack Tanner in Man and Superman, who can afford to choose socialism without giving up a bourgeois, or higher class still, lifestyle and companion set, as Shaw himself did. See below the stereotypes that run through his plays and fill out the picture of a society where characters who represent openly the working class do not exist or are compromised by the action (as in Pygmalion) – from left to right they are the REVEREND SAMUEL GARDNER played by Kevin Doyle FRANK GARDNER played by Reuben Joseph – to complete the filled out figures of his those who span the class system and exposes in the form of MRS. KITTY WARREN played by Staunton. Samuel Gardner is a comic vicar who represents the facade of middle class religious principle hiding a past, and some present unprincipled desires, that belie the mask. His son Frank the usual kind of cynical young man on the make – aware of the power and attraction of wealth and social status, and willing against all emotion or principles to drop anyone who compromises his desire to attain these and keep a superficial sense of reputation, could be in any Shaw play, offering delightful comic relief with a serious point to it. Principles do not guide successful bourgeois lives, and neither do ideals like romantic love.

Then there is the regulation artist figure, an asexual Oscar Wilde, in MR. PRAED played by Sid Sagar (righr below) and the corrupt aristocrat SIR GEORGE CROFTS played by Robert Glenister (left). These figure are almost allegories of the principles of a romantic idealism, ignorant of the world and certainly accepting it without partaking other than in the subsistence it offers, and producing art that has not a care for political and social principle, and in reality is entirely irresponsible. Croft represents naked capitalism, taking profit from capital without too much worry about anything ‘dirty’ in the businesses it covers:

Why the devil shouldn’t I invest my money that way? I take the interest on my capital like other people: I hope you don’t think I dirty my own hands with the work. Come! You wouldn’t refuse the acquaintance of my mother’s cousin the Duke of Belgravia because some of the rents he gets are earned in queer ways. You wouldn’t cut the Archbishop of Canterbury, I suppose, because the Ecclesiastical Commissioners have a few publicans and sinners among their tenants. Do you remember your Crofts scholarship at Newnham? Well, that was founded by my brother the MP. He gets his twenty-two per cent out of a factory with six hundred girls in it, and not one of them getting wages enough to live on. How d’ye suppose they manage when they have no family to fall back on? Ask your mother. And do you expect me to turn my back on thirty-five per cent when all the rest are pocketing what they can, like sensible men? No such fool! If you’re going to pick and choose your acquaintances on moral principles, you’d better clear out of this country, unless you want to cut yourself out of all decent society.

Yet again the play dramatises, quite brutally here, the interplay of ‘principles that define Life’ that are in deficit by Shaw’s standards. For croft ‘decent society’ is a facade for financial transactions that no-one talks about much – whether in manufacture or the provision of female services, even that called marriage – which the play makes analogous to prostitution. But all kinds of ‘principle’ are suspect! Take this exchange between Praed and Vivie once the latter – having renounced love of Frank, also renounces the principle of the ‘romance of life’ or art embodied in Praed, Asked to speak about anything else in Act IV he says::

PRAED. I’m afraid there’s nothing else in the world that I can talk about. The Gospel of Art is the only one I can preach. I know Miss Warren is a great devotee of the Gospel of Getting On; but we can’t discuss that without hurting your feelings, Frank, since you are determined not to get on.

VIVIE. Mr. Praed: if there are really only those two gospels in the world, we had better all kill ourselves; for the same taint is in both, through and through.

Shaw treats that exchange a little differently, for he has (between Praed’s admission of his partiality as a man of the very limited principles offered by Art and Vivie’s riposte – only to him) Frank underlining the point that there is a case for the bourgeois concept of ‘character‘.

PRAED [diffidently] I’m afraid theres nothing else in the world that I can talk about. The Gospel of Art is the only one I can preach. I know Miss Warren is a great devotee of the Gospel of Getting On; but we can’t discuss that without hurting your feelings, Frank, since you are determined not to get on.

FRANK. Oh, don’t mind my feelings. Give me some improving advice by all means: it does me ever so much good. Have another try to make a successful man of me, Viv. Come: lets have it all: energy, thrift, foresight, self-respect, character. Don’t you hate people who have no character, Viv?

VIVIE [wincing] Oh, stop, stop. Let us have no more of that horrible cant. Mr Praed: if there are really only those two gospels in the world, we had better all kill ourselves; for the same taint is in both, through and through.

‘Character’ is not a description of the bourgeois individual but a principle of individualistic self-interest that unites energy of being with the restraint of personal ethics to avoid anything excessive – Frank speaks for himself here, at least how he wants to appear in order to ‘Get On’. But this confuses the point Cooper wants to get out of this exchange – that Vivie is not just a sage of the modern will to succeed on one’s own merits but of the distrust of the old domains in which the sages once dwelt: the Palace of Art. I like it that she does not accuse Praed of ‘cant’: it makes her too much a mouthpiece of Shaw, which compromises her principle of ‘Getting On’ about which Praed is right and shows that Vivie is actually not just intellectually wary of art but emotionally too for its encapsulation of nothing that will save us from death, for some people who are excluded from that principle.

I think another reason Cooper edits this is that he takes, as few other readings of the play do seriously, Shaw’s comparison of his own play to a ‘tragedy’, such that, in this reading I found the echo of another tragedy of parents and their children almost parodied in this exchange:

MRS. WARREN. Listen to her! Listen to how she spits on her mother’s grey hairs! Oh, may you live to have your own daughter tear and trample on you as you have trampled on me. And you will: you will. No woman ever had luck with a mother’s curse on her.

VIVIE. I wish you wouldn’t rant, Mother. It only hardens me. Come: I suppose I am the only young woman you ever had in your power that you did good to. Don’t spoil it all now.

MRS. WARREN. Yes, and you are the only one that ever turned on me. Oh, the injustice of it! The injustice! I always wanted to be a good woman. I tried honest work; and I was slave-driven until I cursed the day I ever heard of honest work. I was a good mother; and because I made my daughter a good woman she turns me out as if I were a leper. From this time forth, so help me, I’ll do wrong and nothing but wrong. And I’ll prosper on it.

if we accept that Bernard Shaw can do emotion as well as the cerebral debate and you will hear echoes of this from Lear to his daughters:

..... Thou art a lady;

If only to go warm were gorgeous,

Why, nature needs not what thou gorgeous wear’st,

Which scarcely keeps thee warm. But, for true need—

You heavens, give me that patience, patience I need!

You see me here, you gods, a poor old man

As full of grief as age, wretched in both.

If it be you that stirs these daughters’ hearts

Against their father, fool me not so much

To bear it tamely. Touch me with noble anger,

And let not women’s weapons, water drops,

Stain my man’s cheeks.—No, you unnatural hags,

I will have such revenges on you both

That all the world shall—I will do such things—

What they are yet I know not, but they shall be

The terrors of the Earth!

And Kitty is as liable to the wrong-headed in speaking to a woman of an epoch beyond hers as Lear the old man of tradition is to his modern daughters. And I think watched properly Evie will not necessarily lack some of the cruelty of Regan, though she makes sense in her arguments. When Shaw sees his play as a tragedy he includes those of Aeschylus and Sophocles and this idea is taken even further by Cooper, who says this in his introduction of being modern in this production yet ‘true to Shaw’s radical vision and preserving the richness and complexity of his language’ :

As I searched for a way to do this, the answer came in the play’s classical dramaturgy. When delving deeper into the text, I noticed how closely its structure resembled that of a Greek tragedy. As with Sophocles and Euripides, the conflict in Mrs. Warren’s Profession is the inevitable culmination of choices made many years earlier. With this understanding, I wondered what would happen if I approached the play as if it were a Greek tragedy rather than a product of the more literal-minded, illustrative realistic theatre of the nineteenth century. This felt like a liberating idea, and it guided my approach going forward.

Now I read that intrigued, but after reading the text had no clear idea of how and why he achieved the feel of Greek tragedy. What follows then is based on seeing stills from the production, where it is clear, as it is not in the Cooper text and its stage directions that the play would invoke a Chorus as part of its effect – called in the cast list ‘an ensemble’. Here is a collage of the appropriate National Theatre stills:

The chorus would seem to represent a kind of collective feminist consciousness that aims to provide a deeper motivation foe Vivie that appears in her language. I do not know how this will play. In many ways the appearance of a chorus representing the working class who still could not or did not take Mrs Warren’s profession as their own might be more telling, but the stills do not suggest that. I can’t quite see how they will work and so will be keen to report back (I won’t look at reviews to get that effect fresh). In Greek tragedy, the chorus often represents a collective voice of the people aiming to reflect the tragedy of aristocrats (often from Thebes) in its own Athenian democratic terms. How to rationalise this will be difficult but necessary to stop Vivie being what Kitty sees in her: and ungrateful, in collusion with lies about herself in order to preserve prudish attitudes. The chorus may represent how principles like giving up an unearned income, yours for the taking but for an unseen collusion with the exploitation and oppression consequent on capitalism, and particularly the commodification of women. Vivie is a ‘New Woman’, a type of the period’s literature but today we need help to see what that might mean, without seeing Vivie as a Margaret Thatcher before her time, rather than the germ of feminist socialism.

The play too ought to remain a problem play where the truths don’t belong to one character. Take this fine speech.

How could you keep your self-respect in such starvation and slavery? And what’s a woman worth? What’s life worth? without self-respect!

The speaker is Kitty not Vivie and she translates self-respect into an appearance kept up in society. Vivie could say this but ‘self-respect’ for a woman has to mean something else – dependence not on inheritance nor current income that is wealth from the exploitation of others, nor on a man, nor based on her sexuality but an Independence from such dependencies, which Kitty cannot have and no longer wants, except in appearance.

Such principles defining a life aren’t easy to describe or show, and Shaw barely raises the point of view of a free working class in any of his plays, but the struggle to define your life with a difference from collusion with most of the status quo does seem a pre-requisite enough to be a principle. I will report back from seeing the play as streamed.

That’s all for now

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

________________________________

[1] Dominic Cooper (2025: 3) ‘Introduction’George Bernard Shaw (ed. Dominic Cooper) Mrs Warren’s Profession London, Nick Hern Books. 3f.