Pinkwashing is not a trait, it is a strategy used to deceive. Where ‘gay rights’ trump human rights then the best trait of our humanity – that desiring free self-expression is being twisted for anti-queer means. This blog works out some issues with the help of Elias Jahshan (2025) ‘This Queer Arab Family: An Anthology of LGBTQ+ Arab Writers‘ , London, Saqi Books.

In truth, no red flags are raised in me by traits, for traits if they exist (personally, I think them a myth proposed by over deterministic thinkers) are hard wired generalised characterics (at the level of scales on which a person may sit such as in Eysenck’s examples extroversion – introversion or stable – neurotic) that together, as a bundle of sometimes interacting traits make up a personality. Fach trait is, again in Eysenck, biologicallly determined and manifests physically in some feature of the central nervous system [CNS] of a personality that is thought to correspond to a measurable rating on a personality trait scale such as the Myers- Brigg Introversuon – Extroversion scale.

Carl Jung laid great stress on such scales too, as determing, although clearly with less stress on the supposed fact according to Eysenck that ones trait score was determined via a physical feature of the CNS., resulting in functional changes and resultant from a psychical outcome of genetic inheritance and / or physical insult to the brain. Hard-wired characteristics are difficult and possibly impossible to change if they exist. Trait theory might be used to suggest that certain behaviours are both inevitable and enduring in persons with that trait subject to appropriate stressors.

But no genuine trait can ever be the trigger for a red flag warning if a ‘red flag’ is meant to signal danger to the one seeing it raised in their cognitive and emotional processing. Traits are the stuff of diversity not of the mesurement of normality, though Eysenck used the precisely in that latyer way visually tje range between each trait extreme as a bell curve in which most fell in the middle ranges. Such mechanisms views of personality have long been considered unfeasible and neither valid nor its tools of measurement accurate enough to vear usage.

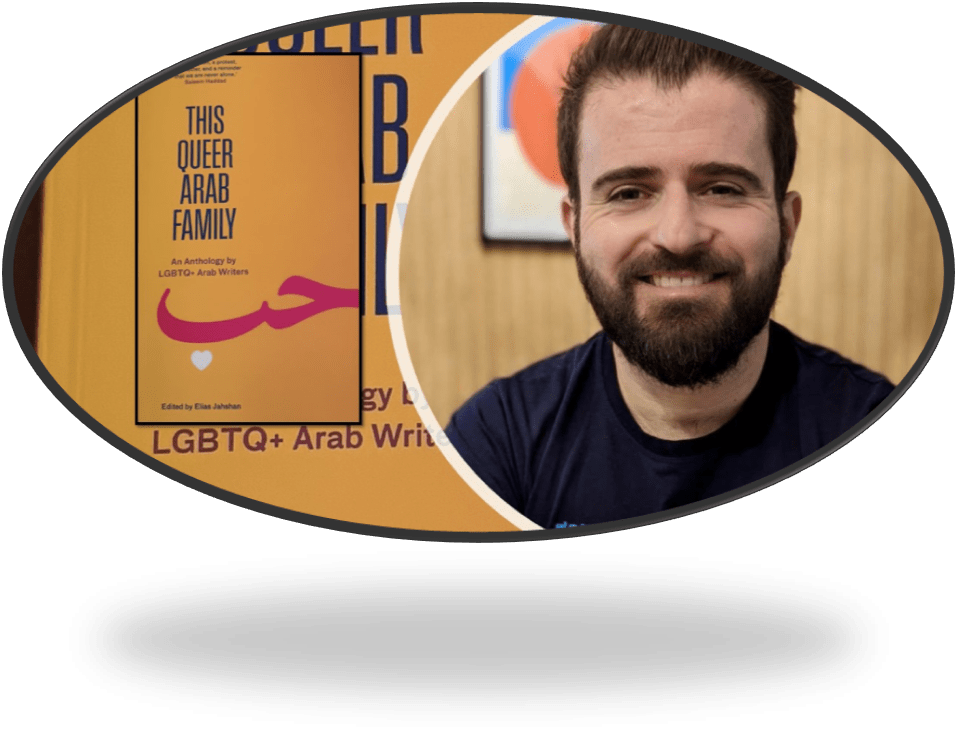

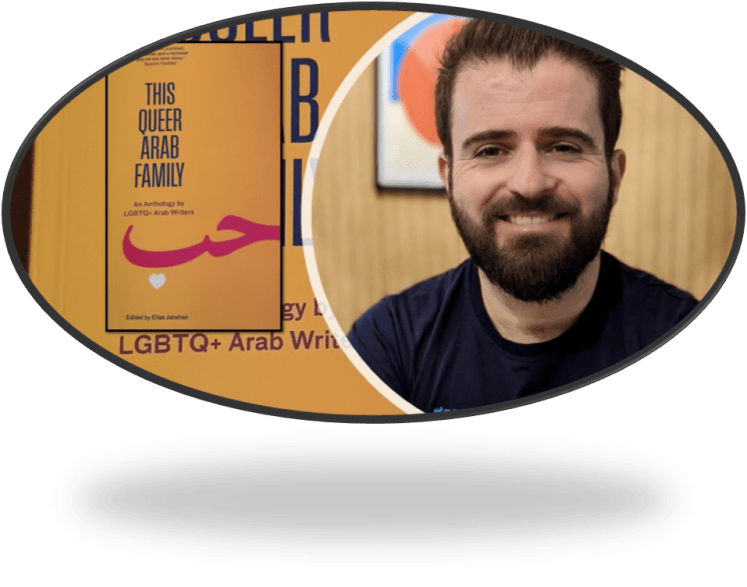

Red flags should not belong to the evaluation of personality traits but to changeable attitudes that, in becoming rigid, appear fixed and unchangeable purely because someone decides they prefer it that way or that it is easier than changing that attitude. The one I want to focus on is that judgement that we call ‘entitlement’, a sense that certain things are the exclusive right only of oneself, or ones considered like oneself and therefore easily comprehended. Entitlement tends to follow situations of power imbalance; though not only in the gross cases of power imbalance but also where intersections of power inequalities produce surmising results. Pink washing is an example of the latter, and is referred to by Elias Jahshan, in the introduction to his new book This Queer Arab Family: An Anthology of LGBTQ+ Arab Writers.

In the one clear and labelled example of the use of this behaviour, there can be no or little argument that it is pernicious and used to deceive its true intent, but the book as a whole suggests to me that we need to identify and root out pinkwashing wherever we see it if our aim is for a honest, just and open space globally for queer people, relationships, behaviours to inhabit alongside choices more normative by some standards, which are queerly various standards anyway.

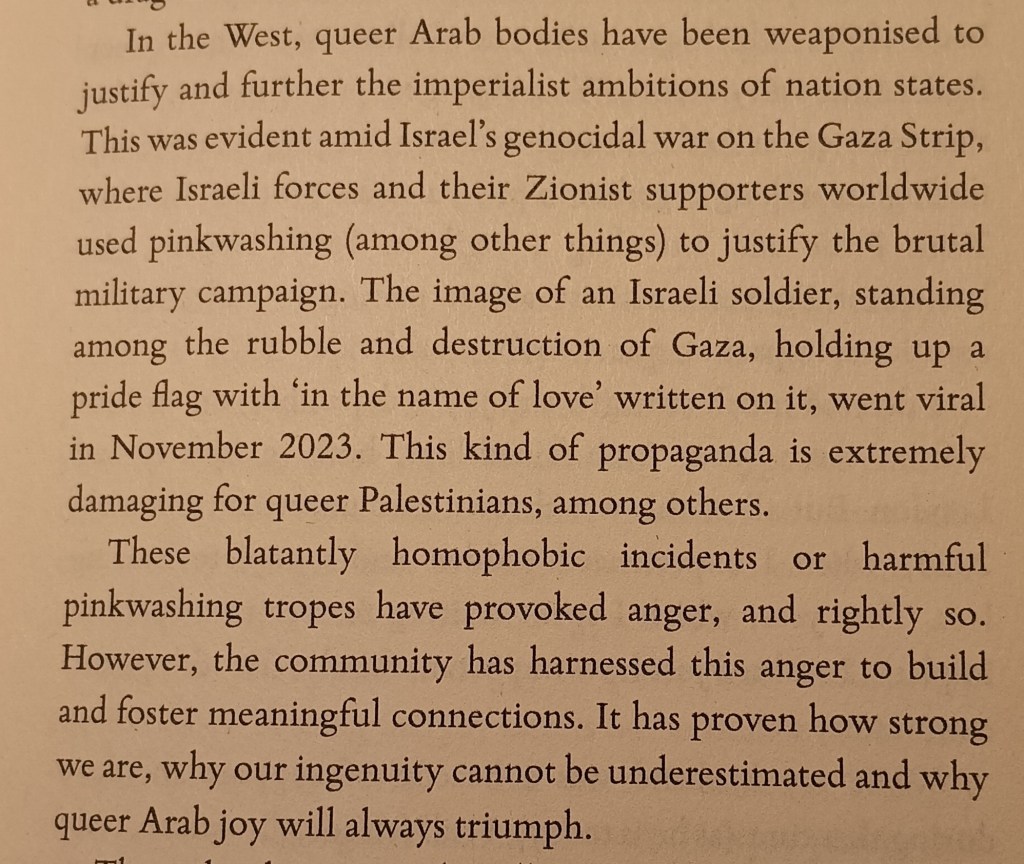

The example of pinkwashing appears below [1]. It is not an isolated example. I have seen but cannot refind one showing two young male Israeli soldiers enacting a proposal of gay marriage, one young man on one knee presenting flowers to the other, stood on a border guard wall overlooking former Palestine settlements that have entirely eradicated of Palestinian families. In Jahshan’s described example, the landscape in Gaza following bombing, brutal, led by drone and long-distance artillery, is proclaimed as the result of acts done in the name of queer love, the soldier even carrying the .most inclusive of LGBTQIA+ flags.

Lest this account be doubted, I am following the above verbal description by the picture itself, which I easily and quickly found by an Internet search (for ‘gay Israeli soldier).

To see this is chilling, particularly the normalising smile of the soldier justifying genocide and destruction of a cultural site of Arab life. But we need to be clear about how such myths work. First, queer love must be thought to have conquered a site that is per se homophobic. But that is how Arab culture is often simply generalised. In the stereotypes Arab families are entirely heteronormative, even when allowance is made for what is often presented as Arab male openness to any source of sex in which the Arab male is the active sexual partner and the hole fucked irrelevant at least away from Arab locales, in the West for example. There is an example of the latter even in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, Mr. Eugenides, the Smyrna merchant.

The Arab family is thought of as entirely heteronormative and structured on patriarchal values. Hence, to publish a book by an Austraian born self-identifying Arab of descent in the South West Asian and North African region (SWANA), the term replaces the Orientalist term Near and Middle East, invented by Western colonial powers. Hence bombing the homes of such families and eradicating even some of its populations can be presented as a liberation of pink power previously repressed in the SWANA region.

That the space for the cultural habitation Arab families is gone might suggest new soil in which queer love can bow only grow. This is why Jahshan sees this picture as imperialism covered over not in whitewash but pinkwash, queer liberation being used as a cover for a genocide considered as necessary for culturally open queerness as what the Israeli’s call democracy, even if a democracy there Jewish heritage alone justifies full entitlement to all its benefits.

So we need a book on the Queer Arab Family to see in what ways it differs from the range of ways families constitute themselves in non-Arab, and specifically Judaeo-Christian, cultures, whether actively religious cultures or otherwise. The book covers diaspora cultures too, where families take on elements of the chosen as opposed to the biological family, though it remains clear that in many ways biological families are often a chosen element in chosen families, with differentiated openness across the family system to the fact that someone is a queer Arab, defined in ways that select from cultures that can be combined at some, and for some at all, points.

What we discover from the anthologies pieces in this volume, all never before published and written because called for by the editor, is that there are no easy commonalities to call out out in them. Even when the queerness of the narrator is not made public in the biological family or the communities in which those families live, we would not be wise to see that partially secreted sexuality as a sign of self-oppression. More than one essay shows us that the emphasis on ‘coming out’ in Western cultures is not a necessary and sufficient condition of a satisfying queer life in any culture, if applied globally and to every environmental and social circumstance. It is perhaps even inconceivable to see ‘coming out’ as the badge of identity when identity itself is relational and varies to setting and conditions of safety for everyone to whom you relate.

Likewise, the relation of sex/gender identity to religion, especially to religions in which family itself is a feature of sanctity is often much more interestingly varied (in the evidence of these essays alone) in Arab cultures across a range of religions and their spread into other cultures. Trans identities are particularly fascinatingly discussed in the essays and expressed variously – sometimes in terms of ancient traditions of trans communities – in other times in hybrids born of intersections of identity with forms of neurodiversity and socio-cultural role – such as the essay that celebrates trans identity through the creation of a dancing robot, which challenges Orientalist myths of the female and sexually available belly-dance (actually the dance is a hip dance) or that which looks at how traditions of informal and illegal Hajj in Muslim cultures can bridge the search for a way to live as both Queer man and a man able to honour his father as he dies from Parkinsons whilst seeking divine recognition from Allah.

Perhaps the most challenged myth in this volume is that one can take pride in one’s queerness apolitically or by choosing to ignore other struggles against oppression – hence many pieces consider how to survive as a diaspora Arab in say America or Australia at a time of genocide in Gaza, and in its effects on Lebanon and parts of Northern Egypt and their Arab diaspora populations diaspora affected by the Nakba. Many of these writers point out that it is not just that the word ‘queer’ applies to all lives forced to appear to be outside the acceptable norm, but that being queer gives insight into the effect of oppression on the site of the body itself. It is finally liberating to read why current politics in the UK, Australasia and USA feels so alienating to us as queer people – it is because politics for us is defined by the right’s obsession with ‘border control’. It is essentially an attempt too to control and expel us as embodied entities. Let’s instance the essay by Randa Jarrar, who says:

You experience a deep sense of pride when you think of how mamy queer folks are helping Palestinians in Gaza. Queer communities excel at organising and collective care because we’ve had to. You understand that the body is a border and queer people understand this borderland existence. You navigate the spaces between acceptance and rejection daily, building community in the cracks of a system not designed for you. And there’s something powerful about people who have been told they don’t belong creating belonging for each other. You [practice care as revolution. When you’ve been told your existence is wrong, simply creating space is radical. In sharing vulnerability, you go beyond survival and into transformation; the kind of deep love that crosses every border designed to contain it. [2]

And finally this book challenges those of us who still think of a monolithically structured Arab family, even in the SWANA region. In the West queer identity has sometimes meant abandoning a family that refuses to or feels it cannot fully embrace queer sexualities. A wonderful essay by Lamiae Bouquentar shows that such a paradigm might be appropriate to some of the functions to which Arab families have been shaped. Lamiae says:

But what happens when exile, postcolonial legacies and racial violence transform the biological family into a refuge, as much as an anchor as a burden? As a member of the Arab Diaspora, family, mine included, is a place permeated by injunctions and morose silences. But it’s also a place you go back to after navigating a hostile world. It’s the place where arms open to tend the wounds caused by the violence of the outside world. The family then becomes a porous border. A territory in which tensions coexist with care practices. We learn how to move in discomfort, how to negotiate our place rather than break ties and burn bridges. We redefine relationships.[3]

We can call all the ways that queer people who are alienated from their own experience because of other ways their intersection with white, western and male privilege feels too privileged to challenge by acknowledging the discomfort of people we prefer to see as ‘strangers’ (outside our boundary) pinkwashing. We think we can defend ‘Gay Pride’ by refusing to get involved in ‘politics’ (by which we mean liberation struggles wherein queer people live and struggle too, by concentrating on broad themes of ‘coming out’ and alliance with border defined racism and anti-trans agitation. If we embrace that view we are deceiving even ourselves that we are not really colluding with the oppressor. But this is not a trait of personality. We can change if we see the urgency of so doing. It may be as difficulty as challenging an addiction (entitlement and power are strong drugs) but it CAN BE DONE!

I loved this book. Read it.

_____________________________

[1] Elias Jahshan (2025:11) ‘Introduction’ in Elias Jahshan (ed.) This Queer Arab Family: An Anthology of LGBTQ+ Arab Writers, London, Saqi Books, 1 – 13.

[2] Randa Jarrar (2025: 56f.) ‘Learning from Other Mothers at a Time of Genocide’ in Elias Jahshan (ed.) This Queer Arab Family: An Anthology of LGBTQ+ Arab Writers, London, Saqi Books, 53 – 67.

[3] Lamiae Bouquentar ( trans from French by Lara Vergnaud, 2025: 180f.) ‘To You, Child of Our Resistance and Our Joys’ in Elias Jahshan (ed.) This Queer Arab Family: An Anthology of LGBTQ+ Arab Writers, London, Saqi Books, 175 – 187.