It brings ‘a tear of joy’ finding truth in fiction and authenticity in mere performance. Here is an example: Liz Duffy Adams’ Born with Teeth; Reflections after reading the text.

In an earlier blog post at this link, I said that I would revisit Liz Duffy Adams play Born with Teeth once I had chance to consider its printed text. The earlier blog had this title (truncated here): ‘…: Seeing (before reading) Liz Duffy Adams’ Born With Teeth in a production at Wyndham’s Theatre, Charing Cross Road, London on the 20th August 2025, 2.30 p.m. However the proposed publication for the hard text, having first been 21st August and then set back until the 29th, was thereafter indefinitely postponed, I sort of lost heart with Nick Hern Books. Thankfully it was published on Kindle so I resigned myself to an electronic version.

Having now read it, I notice that I had ended my first blog portentously (perhaps I now have to admit that is my style) thus:

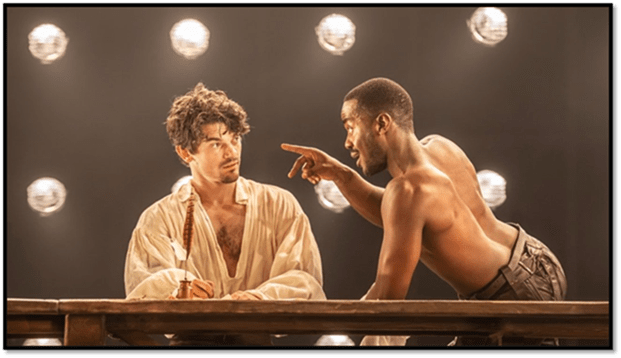

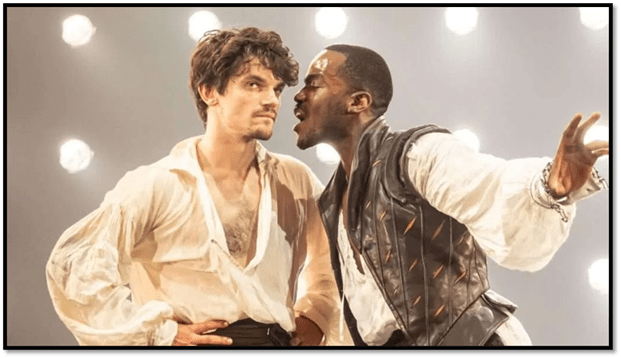

I also felt a kind of mystery in the verse that strongly conveyed Renaissance methods – are parts in the play written in blank verse? I yearn to see. Moreover, even if not, how was the management of the prose kept so flexible between the ‘high’ and ‘low’ (by which sex is usually indicated but also plodding ‘work’ too), the passionate and the everyday, the tragic and the comic. When the play comes, I will read and consider, and write up if I can, for this is truly living theatre which transcends the places in which it is merely bodily enacted – I say ‘merely’ but there is nothing mere about some actor’s bodies offered to us, as these so generously.

Well let’s face error number 1: this play is only ever in blank verse when it cites blank verse lines from Henry VI or other plays – either by Shakespeare or Marlowe. In doing that it makes confident attributions of the parts of Henry VI that some scholars believe to be Marlowe’s, such as Sussex’s entreaty on departure to his wife Margaret, attributing the reply by Margaret to Shakespeare but role-playing the manner of the relationship between Marlowe and Shakespeare – the former all ‘masculine’ rant, the latter all ‘feminine’ versions of emotional intelligence and gentle admonition of males whose language too easily turns to the rhetorical blame of others for their own hot-headed anger at a world not so easily conquered by bluster alone:

Enough, sweet Suffolk; thou torments thyself, And these dread curses, like the sun ’gainst glass, Or like an overcharged gun, recoil, And turn the force of them upon thyself.’

Suffolk is all bad-tempered phallic symbol (an ‘overcharged gun’) and is unable to see that his target is as often himself – his image in the mirror (‘glass’) whatever his rhetorical intention. It is clear that Adams intended the attribution of this to Shakespeare to be a warning against Marlowe – perhaps more than that for at this time he already knows he has charged the dirk himself against Marlowe (in order to save himself from the effects of the latter’s angry flare ups), which in the hands of Sir Walter Raleigh’s agents will rip out Marlowe’s guts, taking his life with it that very evening.

There is no doubt then that Adams knows how blank verse is handled – and differently by each of these dramatists – but chooses not to employ it in her own invented conversations – however tender the intended effect. As an example one might cite that time in which Marlowe speaks of how his sexuality is as inflexible as his temper – ever pointed towards men – whilst Shakespeare benefits from the prevarication possible to his sexual (and dramatic and rhetorical) flexibility:

WILL. I can’t keep jumping out of my skin with each scare. And the fact is, I think… I think you don’t want to do me harm. Do you?

KIT. Of course I don’t. Of course I don’t. Can’t you read me by now? I want to wrap you in wool and put you in a trunk and take you out at parties to say, can you believe this fool? But he’s my fool. Harm you, damn you, I want to run howling through the world with you like a pack of wild dogs.

WILL. You really ought to get married.

KIT. I’m not like you. I can’t trim my sail for every wind. I don’t have your flexibility. I am that I am, and I can be no other. And that being so. That being so. I make no promises. I have said it over and over.

WILL. That’s just it. Over and over. And every time, the dagger’s more blunted.

KIT. Jesu, I could weep. You have no idea. Round and round we go, and so the wire snare is tightened, not loosened.

Perhaps prose alone has the flexibility required for the twists and turns in this dialogue. Will keeps insisting Kit scares him by being inflexible, merely because the world is not fashioned around his desire and needs, and though he spies on the world to keep ahead of its ploys, he will not accept its ways of means of being secure by being hidden under many masks – to suit the circumstance – like marrying though one is attracted sexually and romantically only to men, or by living together with Shakespeare in London at those times when Will is not in Stratford with his wife. As a result he denies the whole history of queerness embedded in complex shifting of masks for the next five centuries. To go ‘howling through the world with you like a pack of dogs’, reminds me of the mottos of the Gay Liberation Front, when I was a member: ‘Better Blatant than Latent’; ‘Gay-Love: It’s a Real Thing’ (in the form of a Coke logo). Will thinks that he has ‘flexibility’ because one MUST have flexibility (he has a future in cognitive therapy) and that Marlowe will not see that. Will sees Marlowe as undefended from harm, just as Margaret sees Sussex prone to becoming his own victim in railing against a world that isn’t shaped by narcissist’s desires.

Will feels love for Marlowe, and shows it by citing back to Kit his own naïve poem The Passionate Shepherd To His Love, as, in fact, many Elizabethan poets did, including Kit’s nemesis, Sir Walter Raleigh. Though Kit, in return, can only use examples from his own work to characterise what Shakespeare’s professions of love mean.

KIT. Come live with me and be my love?

WILL. And we will all the pleasures prove.

KIT. I thought I was meant to be the mad one.

WILL. It is madmen like us who reinvent the world, when no one is noticing. Will you?

Pause.

KIT. I won’t. Slight pause. I don’t want to reinvent the world. I want to live in it, I want to plunder it, I want to rampage through its every part, to fuck it silly and live to tell about it. The world is dangerous and stinking and cruel and so I belong to it utterly. Your utopian vision is ridiculous. You are ridiculous. Did you think I’d say yes? Do you think I’d consent to be your Ganymede, your Gaveston, kept boy to your King Edward?

Will believes we can re-imagine the world even whilst being unable to change it except in mutual receptions of it that embrace the a-normative, to Marlowe, ‘utopian visions’. Will accepts the world is selfish and wants to reflect that in his own selfish pleasures. Could that have been done in blank verse – not without carrying into the play something quite false – the sense that we are aping the geniuses of the past, rather than embodying them in ways understandable to a largely post-literary culture.

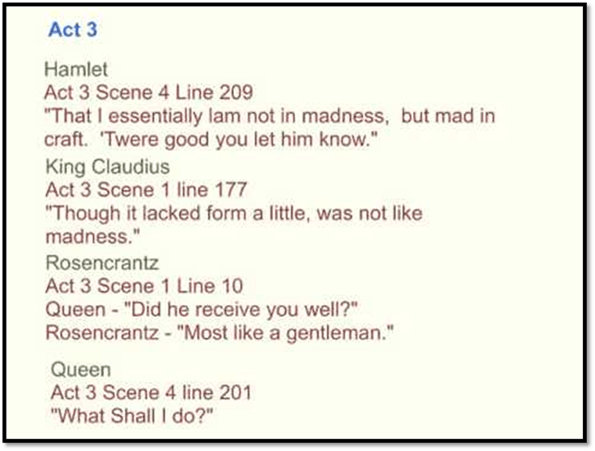

One thing I did find useful in reading the text, is in clarifying my own memory of the play as I saw it. In the earlier blog I said:

In the first scene (1591) the authors are working on the scenes featuring La Pucelle, Joan of Arc (from Part 1) about whom they disagree – Shakespeare wishing to find some nobility in her, Marlowe not so. Likewise they discuss (was that in the second scene – I can’t remember where that’s why I need the text) the scenes in which the revolutionary Jack Cade appears, which are in Part 2, where again Shakespeare takes the ‘romantic’ view of the popular rebel in Duffy’s play whilst Marlowe is more the heroic monarchical reactionary – a kind of Tamburlaine of the quill.

Let’s put my ‘old self’ of that blog out of its misery. I was correct to think that the central discussions of the three scenes of Adams play focus largely on the three Henry VI texts, as if they were written in sequence from Parts One to Three, which some scholars doubt. But the Jack Cade scenes in Henry VI Part Two are indeed discussed in Scene 2, assuming a break from the completion of Henry VI Part One between the scenes, and Scene 3 is, as we seen focused around some of the most mature verse of Henry VI, Part Three, which Adams insists was co-authored in a specific way based on distribution of roles. In that final scene again Kit writes and enacts (as directed by Will) another ranting Tamburlaine, a scheming Barabbas from The Jew of Malta. So I got one thing right through my doubts.

What I did not recognize is a particular beauty of the play in its reference to the influence of Marlowe on Shakespeare as a dramatist and symbol of reckless self-pride (hubris) in his later mature plays. The final soliloquy of Will runs thus, after Marlowe ‘exits’ to a death he knows he can’t avoid and in which Will was complicit:

WILL turns to the audience. WILL. Yeah… did that happen? It’s true, Kit went to his reckoning and I… well, you know. I will say… I’m ever after writing Kit back to life, writing breath back into his lungs, again and again; even when I think I’ve left him behind – ah, there he is again. There it is. Forgiveness, absolution, death and resurrection, love lost and found – it’s all we can do, all of us grievous grieving souls, forever willing our immortal longings into whatever being our pitiful powers may. Oh Kit. You should have died hereafter, you should have lived. I wish I could tell you: I did what you asked of me. I kept my promises. Do you hear me? I kept my promise.

Will here admits that the play and even he in it is a fictional recreation from barely known facts, but he claims something about Kit’s after-life in his own ‘work’: ‘… I’m ever after writing Kit back to life, writing breath back into his lungs, again and again; even when I think I’ve left him behind – ah, there he is again. There it is. Forgiveness, absolution, death and resurrection, love lost and found’. Those are indeed Shakespeare’s themes in the late plays but why should they resurrect Kit? They do, I think Adams suggests, because Will will until his own death feel as if Kit’s death was the loss of his own integrity as a lover, writer and man. How would that be manifest. Earlier I quoted Adam’s words for Kit as professing to Will that ‘I want to run howling through the world with you’. Would Will have such a simple word in his conscience in his greatest play of love misrecognised, scorned and not regained till its object is lost: King Lear. He might if Kit had said to him about his early writing something like this too:

KIT … You’ll write your whimsical pastorals, your blood-drenched revengers, you’ll please the rabble and the censors and hide your greatness for fear of being seen.

WILL. Greatness?

KIT. Don’t get excited, I just say it’s possible. But it won’t be, because you’re too small. You’ll bury your true self and remain invisible for all the time to come. Whereas I stand naked to the world’s winds and howl howl HOWL along with them, and I will be immortal.

KIT picks up his doublet or something, preparing to go.

For, of course Will does not to go on to write plays as simple as those before May 1593, he writes ones in which refined educated need goes unhoused and stands ‘naked’ on a heath, and on the death of a daughter, Cordelia, whom has been rejected says, carries her corpse onstage in Act 5 Scene 3 (line 308ff.) with these words:

LEAR

Howl, howl, howl! O, you are men of stones!

Had I your tongues and eyes, I’d use them so

That heaven’s vault should crack. She’s gone forever.

I know when one is dead and when one lives.

She’s dead as earth.—Lend me a looking glass.

If that her breath will mist or stain the stone,

Why, then she lives.

KENT Is this the promised end?

EDGAR Or image of that horror?

ALBANY Fall and cease.

LEAR

This feather stirs. She lives. If it be so,

It is a chance which does redeem all sorrows

That ever I have felt.

Could Shakespeare have thought his wishes would make him live have Kit live again or mourned Kit thus (that he’s ‘gone forever’) with his howling in the knowledge that his survival instinct was one that blinded him to love? It is part of the richness of the play that it is possible to think this – though it satisfies without any reference to the two historical dramatists revived in it.

However once one sees such resonance, you see it throughout on reading the text. This one spoke out aloud even in just hearing and seeing the play, from Scene 1:

WILL. I just want to write.

KIT. Who doesn’t, but not enough money in the theatre, not nearly, and even if you can write straight poetry – can you I wonder – you’ll only be hand-to-mouth.

WILL. As opposed to hand-to…? Gesture of wanking someone off.

KIT. Ha, what scorn! Haven’t you heard, we must live by our wits or die with empty bellies.

WILL. Perhaps I’d rather an empty belly than a stuck one.

KIT. What, do you fear a dagger?

WILL. I’m not a fighting man. Nor treacherous.

KIT. Treacherous?

WILL. I fancy the work you’re talking of requires disguise. Counterfeiting, equivocation, betrayal.

KIT. And all that’s too mucky for our bare-faced Will? No disguises for you? I wonder. Just exactly who you seem, is that it? An open book?

The ironies in this scene are opened out through the play. By Scene 3, Shakespeare enters to Kit in disguise (it is in the tavern now ‘closed’ not Kit’s home as I reported in the earlier blog) – a disguise associated with death and bringing the message of death perhaps awaiting Kit because of Will’s ‘equivocation, betrayal’ of Kit to Walter Raleigh. Nothing could show more ‘equivocating’ as a behaviour. The play insists that the immature Will does not yet know that these features of the spy’s world are also those of the best dramatists, and late Shakespeare par excellence. If Will isn’t an ‘open book’, opening a page of Shakespeare’s First Folio is to find immediately that no-one is ‘exact who’ they ‘seem’: Women turn out to be men and vice-versa, absent people to be present ones, class status a semblance.

But what comes across too clearly is the way that this play takes the themes of betrayal and equivocation into queer politics.

KIT …../ Who do you fuck, boys or girls?

WILL. I – what – how is that –

KIT. Oh, both? Equivocator! Well, I do see your point, a hole’s a hole when all’s said and the candle’s out.

WILL. That is not at all what I –

KIT. Of course that’s not the legal point of view but only poor buggers hang for it.

WILL. I’m quite sure I can get this play written before I’m hanged for sodomy; may I trust you for the same?

KIT. Oh, fear me not for that, I am all discretion. On a fine day. When the wind is southerly.

The discussion of sexual behaviour is frank but not to Will’s taste, who flounders with answers to such direct questions and is therefore truly an equivocator but not necessarily saying anything directly where hiding is the best policy in a world where ‘sodomy’ is a hanging offence. Of course it is no accident that Adams gives Kit a phrase of Hamlet’s in this scene from Hamlet Act 2, Scene 2 (line 399ff):

HAMLET …. But my uncle-father and aunt-mother are deceived.

GUILDENSTERN In what, my dear lord?

HAMLET I am but mad north-north-west. When the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw.

Yet again we are meant to see, if we know the plays – and that need not be assumed to enjoy this one – that Shakespeare remembered Marlowe as a maker of apt phrases for a mercurial disposition, when Shakespeare will later want one of his characters to ‘counterfeit’ madness. But Marlowe will never appear as a lover. In Scene 2 he taunts Kit for his openness about queer matters in the theatre – in the refusal to hid them: ‘I read your Edward the Second while you were away – how can you get away with that?? A whole play about a king’s boyfriend?’ And later, Will has worked this up into a whole theory of what Keats would call ‘Negative Capability’, of fictive creation that is akin to a deliberate evasion of facts that get in the way, whether about yourself or others:

WILL. That is the difference between us, I think. You expose yourself with every breath, with every line, to read you is to know you with glittering specificity, I knew you before we’d even met.

KIT. You know less than you think.

WILL. I want to disappear. I want to be invisible. I want to write about kings and villains and love and war and life and be as unknowable at the end of it all as I was before I wrote a word. I want to hide in my work like an outlaw in the forest – hunt as you might, you won’t find as much as a potshard left behind.

KIT. And that’s it. Who but an outlaw need be so sly? Who but someone with desperate crimes to hide?

Hiding like an outlaw is so premise a prophecy of the continuation of queer history much later that it is intended I believe to have that weight of meaning. From a play about dramatic styles we soon segue into a play about what it mean to be ‘queer’ and the decisions about survival in the world that were to hang from it.

And the means of survival of queer people also becomes a way into a manifesto about the ineffability not only of God but also of concepts like love. For Will (but predicting Hamlet again):

meaning in our human world is a lucid mystery, full of light, ungraspable. That there is more in heaven and earth than we can dream of. And that ineffability gives me a strange comfort. If I can understand God, with my poor understanding, then He cannot be very great. I need Him to be greater than I can know.

As for the ineffable, Kit undermines it by saying there isn’t anything he can’t ‘eff’. And yet again we are on the cusp of worlds – one where love is only sex and one whose purpose lies beyond the ‘effing’ of holes. In fact both Kit and Will live in the latter, but Kit becomes inarticulate when he must choose to live outside clarity of direction, in the obscure world most of us live in and Shakespeare could recreate. Adams says in her Preface to the text that her interest in this play concerns:

The question of how artists navigate such regimes while keeping art – the stuff that makes life worth living – alive, is something I find lastingly of interest.

But there is more to it than that. For I often think of ‘love thus. It is a concept with a poor press now, much maligned, and seen as an epiphenomenon as much as art is. If I had a question I want to pursue to eternity, it is how we could, without giving in to hetero- and homo- normativity, as queer men: ‘navigate such regimes while keeping love – the stuff that makes life worth living – alive, is something I find lastingly of interest’.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxx