The ‘Nostos’ theme absorbs all the energy we ought to have for thinking about our responsibility for creating ‘homelessness’

I wonder if the magic associated with the film E.T. – The Extraterrestrial is not a version of the staple myth of the Western world – the Homecoming or Nostos theme. It is the stuff of epic adventures – however dressed up they be in marvellous adventure that diverts us along the way. The real meaning of Homer’s The Iliad is not thought to be fulfilled until his sequel: The Odyssey (a tale of serial adventure on the way home). What appeals about that strange looking E.T. is that his eyes are continually cast, and his finger pointed at and lit, towards ‘Home!’ In truth, this softsoap is truer than we think – we get sentimental about aliens, but that can only be sustained it turns out when they show that they need to go home before we repatriate them forcibly in the promised manner of Reform, but legitimised by every party including the present one in sad bad governance.

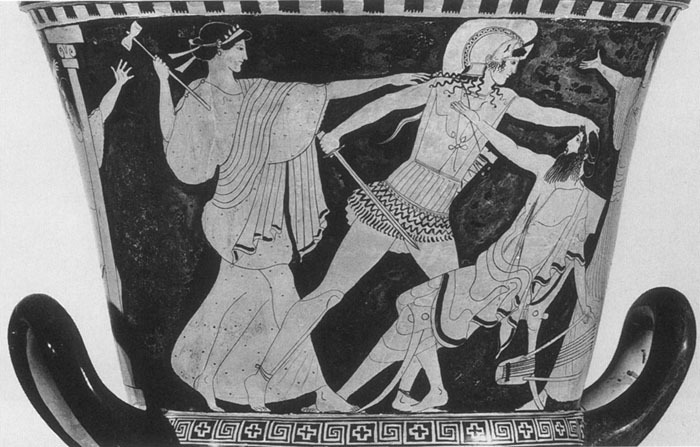

In truth the Nostos theme is a complex one and rooted in imperialist adventure, from Greek settler colonialism onwards, and the view that the colonial returner merely elevates the value of home by elevating it by conquests that he, this is a patriarchal myth after all, does in the name of his home. Homecoming is predicated moreover on rendering others ‘homeless’, and glorying in that achievement. That is the meaning of the Trojan War in The Iliad, that story of dispossession, enslavement, and appropriation. These are the myths that Israel now uses in its conquest of Gaza City and its eventual settlement of it by settlers in the name of a commandeered and reinterpreted Zionism. Gaza will be the homeland, they say because it always was – pointing to mythical narrative and justifying the defeat of Palestine as if it were the defeat of the Philistines (one of the sources of the name Palestine deriving thus).Meanwhile the erasing of ‘homes’ and displacement that is the emblem of a mass of created homelessness, continues apace whilst we, in the West, long term beneficiaries of a global capitalism predicated on setter colonialism, or more direct imperialism, turn a blind eye.

Sometimes, that eye, though turned away, is not so blind. It fills its hungry gaze by visual celebration of our own ‘homeland’ by making it uncomfortable for those we wish to alienate, emphasising their dependent status (in which case they are welcome – as the Greeks welcomed the slaves it displaced from Troy in myth, from its colonial adventures in reality) or their need to become the itinerant homeless – enforced nomads whom we can then despise for their unsettled ways.

That is more or less the story a more reflective (and on the way out) Greece told in the 4th century BCE in Euripides’ The Trojan Women, where the loss of a matriarchal home is mourned in the lives of many mothers, who must embrace even sexual slavery to their conquerors and the murder of their children symbolised in the death of Astyanax. Nothing much changes:

Heroes are heroes because they conquer but also because they dare to do so by boasting about ‘the furthest they have ever travelled from home’. Moreover, they do so once they have returned ‘home’ in geographical or imagined space – in the later case, in settled colonies that have become parts of the ‘homeland’. About the people who become dispossessed or ‘homeless’, we lose no sleep: the real lesson of The Bell Hotel stories in Epping Forest. The ‘distance from ‘home’ of an asylum seeker must be their business and their responsibility, whatever the possible tragedies that brought it about. We could sympathise if they pointed their own way to ‘outer space’, there to find their ‘home’ (with no need for us to visualise that home).

The paradigm for the current conquest of Gaza is strangely laid bare in Milton’s Samson Agonistes wherein Samson’s father’s celebration of his son’s heroism for his homeland, Israel, and his return to that homeland, is honoured even though Samson is dead:

Come, come, no time for lamentation now,

Nor much more cause, Samson hath quit himself

Like Samson, and heroicly hath finish'd [ 1710 ]

A life Heroic, on his Enemies

Fully reveng'd, hath left them years of mourning,

And lamentation to the Sons of Caphtor

Through all Philistian bounds. To Israel

Honour hath left, and freedom, let but them [ 1715 ]

Find courage to lay hold on this occasion,

To himself and Fathers house eternal fame;

And which is best and happiest yet, all this

With God not parted from him, as was fear'd,

But favouring and assisting to the end. [ 1720 ]

Nothing is here for tears, nothing to wail

Or knock the breast, no weakness, no contempt,

Dispraise, or blame, nothing but well and fair,

And what may quiet us in a death so noble.

Let us go find the body where it lies [ 1725 ]

Sok't in his enemies blood, and from the stream

With lavers pure and cleansing herbs wash off

The clotted gore. I with what speed the while

(Gaza is not in plight to say us nay)

Will send for all my kindred, all my friends [ 1730 ]

To fetch him hence and solemnly attend

With silent obsequie and funeral train

Home to his Fathers house: there will I build him

A Monument, and plant it round with shade

Of Laurel ever green, and branching Palm, [ 1735 ]

With all his Trophies hung, and Acts enroll'd

In copious Legend, or sweet Lyric Song.

Thither shall all the valiant youth resort,

And from his memory inflame thir breasts

To matchless valour, and adventures high: [ 1740 ]

The awful awesomeness of that verse is that the ‘years of mourning’ to come in Gaza and all ‘Philistian bounds’ (Palestine) is celebrated. The homeland is geared to defeat antisemitism, which it sees everywhere, even where it isn’t, but is just a reminder that Zionism was a remnant of the nineteenth-century settler colonialist paradigm.

Recently the BBC has shown pictures of how Palestinian farmland in the West Bank has been taken over forcibly, and with IDF collusion, as in honour in other ‘Philistian bounds’ to the victory that total dispossession, sometimes by genocide, that has occurred in the Gaza strip, whilst ‘Gaza is not in plight to say us nay’.

Let’s recognize that honouring our homecoming must celebrate connected themes:

- The extension of our homeland over the distance we have travelled;

- its annexation, at least psychologically – in memory but perhaps even in adventurous project for the future;

- the greater glory of home.

Greek dramatists were often circumspect about 8th century BCE or earlier visions of glorious homecoming and Aeschylus’ Agamemnon comes home to be taught a lesson about putting conquest and adventure over staying put and disregarding the favour of the prevailing adventurous winds – for if he had he would not have sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia, nor lost his wife to another king and not been murdered as the climax to his nostos celebrations.

Who weeps for Agamemnon? Certainly not the enslaved Trojan princess Cassandra brought home as a slave-sex-toy and murdered too for her pains! Latterly, homecomings are not symbols of grandeur but of further degradation – as in Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa, where the inner tensions of Irish society are tearing home apart on the nostos of a celebrated mock hero wearing Imperial plumes.

We are at a dangerous time in the UK. We have a rudderless unprincipled government unable to determine the threat that the most awful of nostalgic nationalism is bringing to bear, and hoping like hell all that middle England cares about is an upturn in economic fortunes unlikely to come after the nostos-led ideology of Brexit has conquered all decency and global communalist feeling. Meanwhile, a frog-faced neo-Fascist leader offers something else, if a ‘whited sepulchre’ whereunto:

Thither shall all the valiant youth resort,

And from his memory inflame thir breasts

To matchless valour, and adventures high:

The rebirth of this kind of mindless nostos-algia will be fed by stories of ‘the greatest distance you have travelled from home’ and how, now you’re back, home has opened its otherwise stony heart for you – making space for heroes out of the meagre spaces (rooms in the Bell Hotel for instance) offered to those escaping oppression, the oppression most often a legacy of European Imperialism’s and settler colonialism.

We need new rhetoric as well as principles to found it upon.

With love

Steven

One thought on “The ‘Nostos’ theme absorbs all the energy we ought to have for thinking about our responsibility for creating ‘homelessness’”