‘”What d’you mean?” / “What do you mean what do I mean?”‘[1] Do we ever know what a person ‘means’? Is that the issue in David Szalay’s 2025 Booker-longlisted novel ‘Flesh‘.

Male novelists, with a deserved reputation for being interested in the nature of contemporary constructions of masculinity like David Szalay are perhaps too vulnerable to it being claimed that they are qualified to write about nothing else. Take Luke Brown’s review in The Financial Times which invokes his ‘All That Man Is, which was shortlisted for the 2016 Booker Prize’ for being able to ‘universalise aspects of contemporary masculinity with particulars from men criss-crossing Europe’ (a description, by the way, with which I fully concur). From then on, Brown’s take on every aspect of the 2025 novel Flesh is spoken about in terms of its reference to masculinity from Szalay’s prose, which we are told ‘invokes Hemingway’s muscularity in single-sentence paragraphs, declarative syntax and inexpressive dialogue that suggests feeling is being swallowed’ (encapsulated he suggests in the increasing comic inadequacy’ of constant male reference – by István and his biological son – to being ‘okay’) to his singular concern with ‘the incessant prompts of desire in a man’s life, the masturbation normally kept offstage, the amoral urges that must be quieted to stay faithful, civilised’ in protagonist of the novel, István. Szalay is finally praised for being willing to ‘describe and reckon with the potentially destructive aspects of’ male character that in ‘Flesh feels especially refreshing, illuminating and true’.[2]

But neither masturbation nor use of ‘okay’, or its equivalent non-commitment to a positive or negative answer like the ‘shrugs’ used by the housekeeper – Mrs Szymancki, are events in, or positions on, life reserved for either István, or his ill-fated son Jacob, but are used for their own self-expression (if it amounts to as much as that) by women. The girl, Noémi, is the first character in the novel to half-talk about the exigencies of ‘masturbation’.[3] As for ‘okay’, the Hungarian waitress, Bori, he meets near the end of the novel uses it[4]. Working class women in the novel like Bori and Mrs Szymancki, or the late middle-aged neighbour who uses the teenage István as a substitute for the sex her impotent husband cannot give to her, are less interested in elaborating feelings than aspirant middle class women like Helen Nyman, who takes on István for his use of the word restrictive coding of meaning:

“What do you mean okay? What does that actually mean?” she says. “When you say it was okay, you’re not actually saying anything are you?”[5]

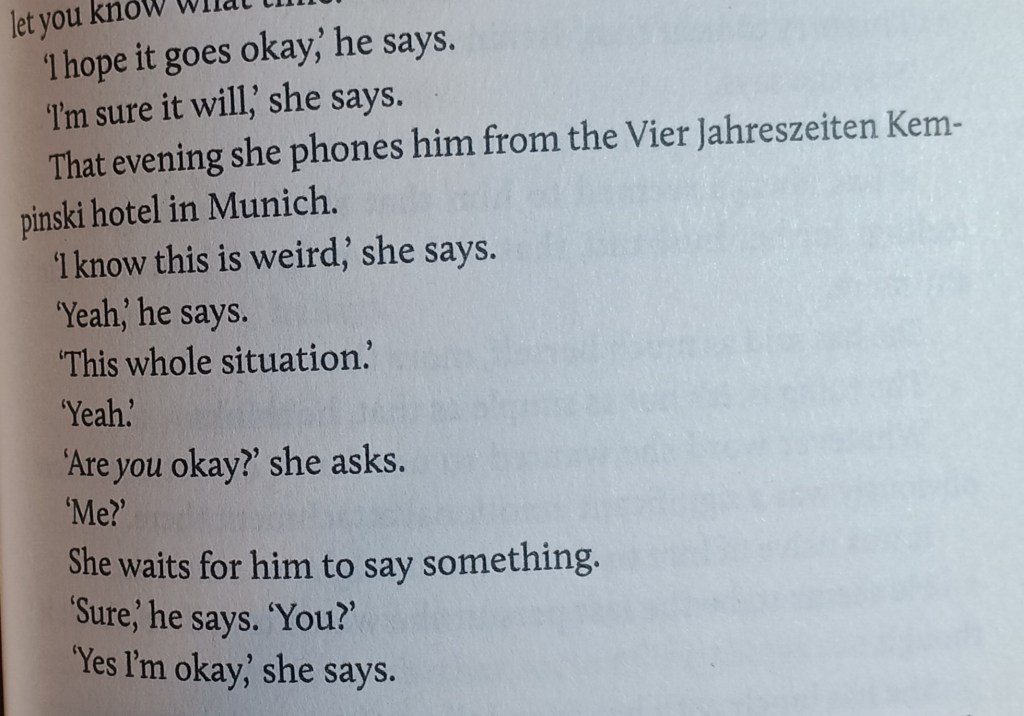

My own view is that the interest in the supposed inarticulacy of men about specific emotions is not really that of the novel but of characters like Helen and the therapy industry representatives within the novel – like those mandated on István at least twice by courts of law. And as Helen loses status and power socially, she too becomes less willing to say exactly what she ‘means’. When asked to explain why she says István has a ‘strange way of looking’ at her and his child’s future, she says merely: ‘I just do’. For ‘okay’ is not the issue in the novel – the issue is that it stands as a coded way of being either willing or unable to elaborate (or find a code sufficient for such elaboration) of what it is we mean by what we say, what we do or what we feel or are ‘really’ thinking. However, ‘okay’ is a word that does do that job as is clear in the exchange between István and Helen when each is least sure of the other on the departure of her flight to visit her dying husband, soon after she offers a ‘blowjob’ to István.

David Szalay (2025: 167) Flesh, Jonathan Cape, London

In the end the issue that this novel dramatises is that it is better to use restricted codes for your meaning, for otherwise it would be too obvious that none of us has that clear a grasp of what we ‘mean’ whether we are talking about our views, preferences, desires or even our very ‘selves’. That is, by the way, not the same thing as Hemingway’s use of ‘show, not tell’ novelistic techniques. I cite the first use I noticed of the term “What d’you mean?” above in my title. It is spoken by Noémi, the first girl István thinks that he is ‘sort of in love with’ on his own initiative rather than as a response to female primary interest in him.[6]

Neither Noémi nor István really want to interrogate their feelings about, or even the facts of, relationships. Noémi actually says that, “I don’t want to talk about it,” though István continues to ask her afterwards why she feels and thinks as she does about things. Their conversation typifies many other tokens of similar conversations between individuals in the novel:

David Szalay (2025: 47) Flesh, Jonathan Cape, London

Being ‘not sure of another’s meaning, or intention is the entire flavour of this passage. The only thing said to be ‘clear’ is that There is no answer to any questions about the other’s meaning, partly because the other insists the meaning is ‘just how I feel’,: being asked ‘why’ that action or feeling confessed is or was the case, they say that it is because ‘I just do’. There is no explanation even from the person who believes that their meaning is transparent; so how transparent is it? After all if someone says: “Do you really not see what I mean?”, the question remains open whether anything is visible, there to be seen at all, or at least ‘seen’ in the sense of being understood. Even asking questions about meaning seem to miss out on meaning and to circle on themselves: “What do you mean what do I mean?”‘[7]

This makes for a convenient formula for the novel’s, and the character’s silences on the causation or meaning of behaviours it is more convenient for them not to understand. The therapist István first tries, in order to cope – perhaps from the trauma involved in his witnessing of, and role in, his male soldier-friend Riki’s death in Iraq – to articulate the event and associated ‘thoughts he has and also the feelings he has about them’, stipulating that ‘he should write them down …, trying to be as precise as possible’.[8] The novel’s development, and István’s, depends on a scene in which a previously unmet man, we later discover to be Mervyn, being saved from attack by men on the street in the old ‘tunnel’ like passage that used to connect Charing Cross road to Soho – by The Pillars Of Hercules pub – alongside Foyles’ bookshop (even before it became Foyles in 2014) – it is a ‘tunnel-passage’ I remember well from student days in London in the 1980s.[9] We never learn why Mervyn frequented that ‘tunnel-passage’ that connected with the sex trade (queer and heteronormative) in Soho very late on dark nights, and not even Mervyn’s late-discovered wife – discovered after István accepts a dinner invitation to his home from Mervyn who first asks him if he has a wife or girlfriend – seems to ask him ‘why?’ István, however, continually vies with Mervyn to stop the latter getting the ‘wrong idea’ about being himself a worker in Soho given he isn’t ‘really into’ watching ‘pole-dancing’.[10]

This is a novel also where so many people find substitutes for the sex they aren’t getting from the heteronormative and conventional sources: the ‘lady who lives in the flat opposite’ with the husband with ‘heart trouble’ who takes his pleasures in gardening and the pub and still can be matey with István, whilst the latter’s substitutive sexual interest in his wife remains unspoken; Helen, whose billionaire husband Karl has become impotent, or uninterested, following his first cancer treatment; Mrs Szymancki; and Bori, whose husbands keep emotional or literal distance from their wives.[11]

The female working-class neighbour insists that a teenage István should never say to her that he ‘loves her’, because, she insists: “You don’t know what that means”. To which the boy characteristically replies: “Why do you say that? … Why do you say I don’t know what that means?”[12] It remains an open question here, whose inarticulacy, for convenience or incapacity, is being demonstrated. One relationship, perhaps even a token of a whole type of such unspoken – unspeakable, relationships buried well under the novel’s surface – to the point of total invisibility and the chance of them not being there at all. That one relationship is referred to when Noémi quizzes István about the substitutive means of having sex and includes her interest in lesbian porn because ‘she finds the men in films so off-putting’, with their “Take that bitch, suck that bitch” sexual take on women. Yet Noémi has already been told, we learn in this scene, that István has, in the past, ‘actually had sex with another man’. We have neither been privy as readers to that telling (or showing) of that scene nor do we learn more here except István’s evasion over that memory’s recurrence in public space:

He told her once, when they were drunk, about what happened in the institution that one time.

He sort of wishes he hadn’t now.

He says, “That was nothing.”

“That’s not how you made it sound.”

“We were desperate,” he says.

“You sure that’s all it was?”[13]

At this point the conversation veers away back to the mutual partaking of another toxic substance. István’s relationships with other males are ones characteristic in evading talk of emotion or thought, either between housemates, fellow-soldiers or acquaintances met in contingency to accidental events – like Mervyn. Of course, there could and will be, no ‘evidence’ of this undercurrent as significant in the novel. It is merely one of the things that is ‘just what is’ and nothing else, unarticulated, or at least unelaborated in a mere expansive linguistic coding, and not to be investigated.

There are two sets of themes in the repertoire of the novel that are contingent to this silence about man to man relationships- the first is the incident which ends in István’s first noted, if complicated in process, referral to therapy – in which his mother is the main agent of referral. The second is the series of times when men become the focus of a death wish, a wish sometimes fulfilled but in one important instance, not fulfilled, despite the fact that István must accept financial ruin, and a return to poverty in Hungary because of it. Let’s take each in sequence:

First, there is a single incident which takes place in István’s first period of work – at a ‘winery’ following discharge from the army and gained for him by his mother on the grounds that he is an Iraqi veteran – a ‘war-hero’, despite his youthful criminal record. It is a desk job and István ‘envies the man who drives a tractor’, which is, after all, a ‘real man’s’ job and not one that where its possible ‘even for his mind to empty of thoughts altogether like it sometimes can do when you do physical labour’. This fullness of mind may relate to the contingent sequence in the narrative, though we aren’t told it does: in a Whitsun long weekend holiday, he lounges on his bed smoking, and then:

He doesn’t know he does what he does next. Something wells up in him. It feels as purely physical and involuntary as throwing up.

There’s a surprisingly loud sound and the door has a splintery dent in it now. [14]

In an incident thus flagged, so unconscious that it cannot be described let alone explained in terms of any cause, it transpires that István has punched a door panel so heavily that he complex fractures in his wrist and hand. ‘Why?’, István might have asked in less tension and waste of spirit and energy. We have few clues, except but that in his drink and drug fuelled behaviour with friends, Norbi and Balázs, some likely young medical students ask him in a toilet where cocaine is dispensed: “Did you kill anyone? … “In Iraq I mean.” This is a difficult one, for we know that, in a sense as a teenager he killed the man with ‘heart trouble’, if unintentionally, referred to above, whose wife he was fucking. Moreover, later, we will learn that his actions may, at least in his mind, have been part of the reason for his friend Riki’s death, though his therapist dismisses that possibility. There is more than enough aetiology for Post Traumatic Syndrome Disorder (PTSD) there the issue is that both István, and the novel, eschew asking the question nor offering unwanted answers.

Even when he speaks to his mother for explanation, her question – a bleak ‘Why?’ to ask about the need to punch a door – the answer is “I don’t know”. [15] That set of question and response without any outcome is repeated when his mother takes him to a psychiatric hospital for assessment. [16] But it is possible (isn’t it?), since the novel’s patterns seem to demand when declarative sentences are missing in explanation – that this is about István’s own inarticulable distress about why he feels as he does about men he either loses (or himself excludes) in his career onwards through life. It is to the therapist alone that the story of his feelings about the dead Riki spill out, where word ‘okay’ again fills an absence for more elaborate explanation in the story of Riki’s dying moments:

For a while Riki was still conscious. He told him it was going to be okay, even though it probably wasn’t. He also knew that after that he’d never believe anyone telling him it was going to be okay. Or maybe he would believe them. Maybe he’d want to believe them so much he would, in the way that Riki may have believed him as they sat there on the asphalt. When Riki lost consciousness he wasn’t sure if he’d died or what. [17]

Second, it is a characteristic pattern in this novel’s events that men that somehow get in István’s way – block a future way forward – become the object of what, with more or less precision, a death wish that is fulfilled. Thus the inconvenient husband with ‘heart trouble’, falls down the steps of the council block after some ‘pushing and shoving’. The novel just delights in confirming or assuring us of nothing about what is going on here:

And in a way he starts to doubt his own memories of what happened.

He starts to wonder if he is remembering it right or not.

He wanted the man dead.

He did want the man dead.

“You wanted him dead, didn’t you?’ the policeman says to him. [18]

Of course Karl is another man who gets in the way István’s worldly career, gained through sexual conquest of Karl’s wife, Helen. This is too complex a narrative though to deal with here, but it applies to men who do not have to die to be swept out of the way because, for any number of reasons, like the husbands of Mrs Szymancki or Bori respectively. But this ruthlessness of desire for death, if not of actual murder, is precisely set aside when István, rather than facilitate the death of his stepson, Thomas, which he could have done without detection or commission of murderous acts, he rescues him from death at the last minute, and as a result is financially ruined even more than was the case when Simon set out to ruin him by public disclosure of his shady financial dealings. [19]

Much of this is about the competitive paradigm of masculinity, proven by winning women from other men (an event which opens the novel on its first page where young István is urged, implicitly, to prove his ‘sex-drive and hence his masculinity by male teen peers. Likewise, it relates to a middle-aged women who seduces him and suggests to him that this proves he is ‘a man now’. [20] It is a theme that ensures that the job role that leads to success for István is that of a ‘security man’ or a soldier, guarding political, sexual and other property in Iraq, Soho and then in a more ‘refined’ world and needs ‘training’ for it. [21] So much is he like a ‘security man;’ that he is mistaken for one even when he isn’t one when he travels to join Helen in Munich.

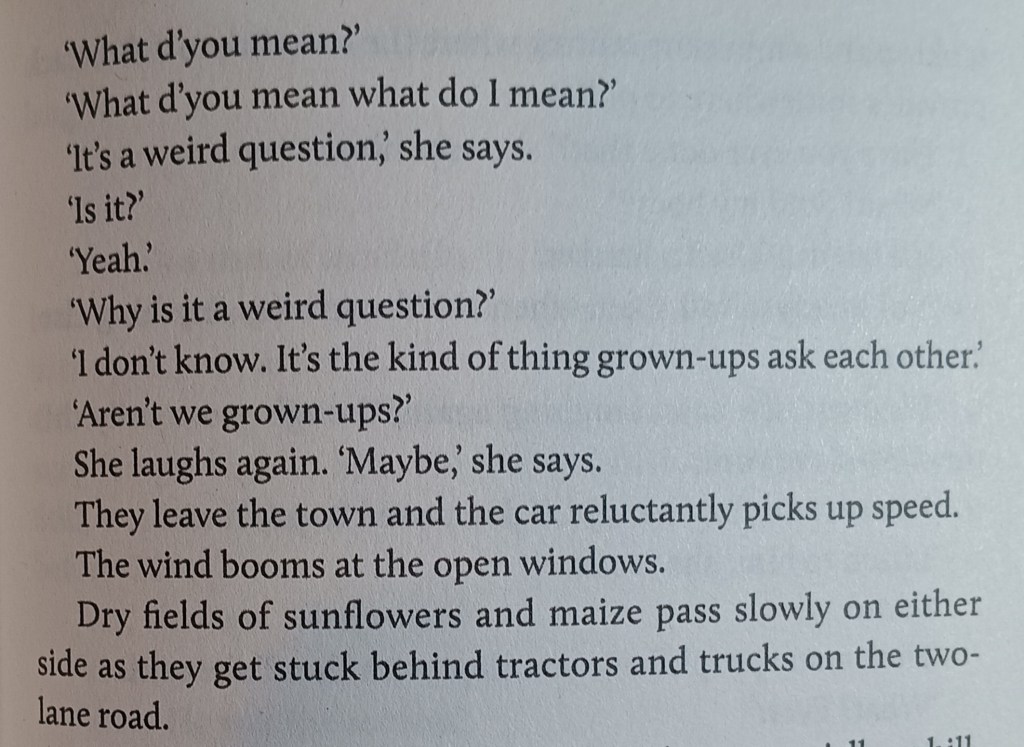

But, as I have already said, though masculinity is a primary role in the novel, all roles defy justification or elaboration. I do not think the key question is: “What kind of man are you?”. Instead it is: “Tell me about yourself”, or even the basic question, which often gets quite existential in this novel: “How are you?” Such question can ask people to elaborate the inner meaning of their character or their role, or character type, or category (down of course to basic class, sex/gender and sexuality categories) in ways that each and every character finds difficult and most impossible to do. It is tested even when young István is too easily shown to be a worse driver than a young women he is trying to impress – possibly why later he is a chauffeur (or ‘security driver’) – but it is the question ‘How are you?’ that launches the that fact that both young people in the car question whether their roles – as gendered or as ‘adult’ are being queried existentially: [22]

It is the question together with the ‘okay’ reference, that Karl’s sister, Mathilde, asks Helen in order I think to destabilize her and remind her of whom her brother’s wife ought to be in public, whilst suggesting she is acting rather stupidly and selfishly with their ‘security driver’ whilst her husband is dying:

” And how are you?” Mathilde asks her. “Are you okay?”

“yes I’m okay.”

“You need to look after yourself”

“I know.”

“You mustn’t let yourself go.”

“I know,” Helen says. [23]

But of course a key exchange in which existential statements are refused is in the prequel to the affair between István and Helen where she actually says: “Tell me about yourself István”. It is a masterly piece of dialogue that can only be read to understand its humour and darkness – not like Hemingway as Luke Brown thinks but more like Harold Pinter at his best. [24]

I think I have said more than enough to say why I think this novel a very good one, but, if I am right, that may be a reason why it will NOT be a Booker winner, but let’s see. Nevertheless it a meta-critical a book – self-conscious about its status as art and querying what that status ‘means’. There are visual artists aplenty in this novel, not least the lesbian friend of Helen, who in the crucial scene at her art show, where István is disgraced because she also invited Thomas, his stepson, is more worried about the critical reception of her art amongst the great and good than the ethics of her actions. In this scene István is talking to the Tory foreign secretary, with whom he has a chequered financial interaction earlier, and his wife about the art:

“I think there’s something interestingly interactive about it,” the foreign secretary’s wife says.

“How d’you mean?” István asks her.

“I think it sort of asks the viewer to investigate it,” she says. “To find their own meaning in it.” [25]

This is broad humour that literally shows that even folk critiques of art have a discourse equivalent to answering a question about its meaning as “I don’t know”, which, in effect, and trying to save face, the foreign secretary’s wife does. There is a need for art to mean, we think but does it elaborate its meaning ant more than anything else. For me, the most interesting piece of art in the book, and a kind of substitute for the novel Flesh that Szalay suspects most readers will read is the small Monet owned by Helen, a ‘six-figure’ priced 5th anniversary gift from her husband.

He looks at the Monet. A beige beach under a grey sky. Some figures on a beach, one of them holding a parasol’. [26]

And what does that mean? ‘How d’you mean?’ what does it mean? Maybe art too must not articulate for us, if we fail to have purpose of our own. But yet we must try to let art have its space and to challenge – not by allowing it to ‘mean’ whatever we want it to mean but as a challenge to the ‘normality’ that otherwise the world asserts. I find this late paragraph chilling as indeed many other T.S. Eliot like references to the seasons being insistent.

There’s something terrible about the way normality asserts itself About the way that summer insists on happening. About the way the chestnut blossom and Wimbledon takes place. [27]

It’s terrible like the Spring that ‘arrives in the Hofgarten’ as Karl dies. [28] For years people tried to find meaning in the seasons until T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land challenged that easy way out but finding hope or anything else in the seasons is as meaningless as believing that Wimbledon occurs as naturally as ‘chestnut blossom’ (and even that is not secure now). And art has a role in reminding us of that dark fact.

It’s a great novel

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] David Szalay (2025: 51) Flesh, Jonathan Cape, London.

[2] Luke Brown (2025) ‘Flesh by David Szalay — a portrait of modern masculinity’ in The Financial Times [Mar 5 2025) Available at: ttps://www.ft.com/content/e1874a77-142a-43c2-aa77-dc841a3a0e84

[3] Ibid: 56

[4] David Szaly, op.cit: 319f, 346 respectively

[5] Ibid: 134f.

[6] Ibid: 40

[7] ibid: 51.

[8] Ibid: 99

[9] Ibid: 107

[10] Ibid 110, 113

[11] Ibid, respectively: 6, 14, … 320f. for example.

[12] Ibid: 29

[13] Ibid: 56f.

[14] ibid: 89

[15] ibid: 92

[16] ibid: 97

[17] ibid: 99

[18] ibid: 34

[19] ibid: 329

[20] ibid: 20

[21] ibid: 121

[22] ibid: 51 (for photographed passage)

[23] ibid: 194

[24] ibid: 134f.

[25] ibid: 262f.

[26] ibid: 291f.

[27] ibid: 317

[28] ibid: 193

3 thoughts on “‘”What d’you mean?” / “What do you mean what do I mean?”‘ Do we ever know what a person ‘means’? Is that the issue in David Szalay’s 2025 Booker-longlisted novel ‘Flesh’.”