Félix Vallotton Le Coup de Vent 1894

A coup in French is literally a ‘blow’ or ‘gust’ but, of course, we know it best in the term ‘Le Coup d’État‘, such as that event on 18 Brumaire where Napoleon took control of French revolutionary forces and thus the state. it has been forever after the term for a violent governmental takeover by force. Can a ‘coup de vent’ (gust of wind) have the same revolutionary change – for better or worse – as a Coup d’État? Certainly, even the first sort of coup can change a bourgeois family’s typical day. But this is a brilliant woodcut precisely because it shows just how much visible order can be disturbed and made to change in ways that seem to have their own logic in middle-class lives. It is not just that we have to hold onto our hats but our clothes themselves seem to have their own dynamism – and that dog barely visible beneath a gust that might be as solid, but no more, than smoke, could easily be imagined to fly rather than merely walk. It is as if time and space were disrupted not just the solid markers of our class position.

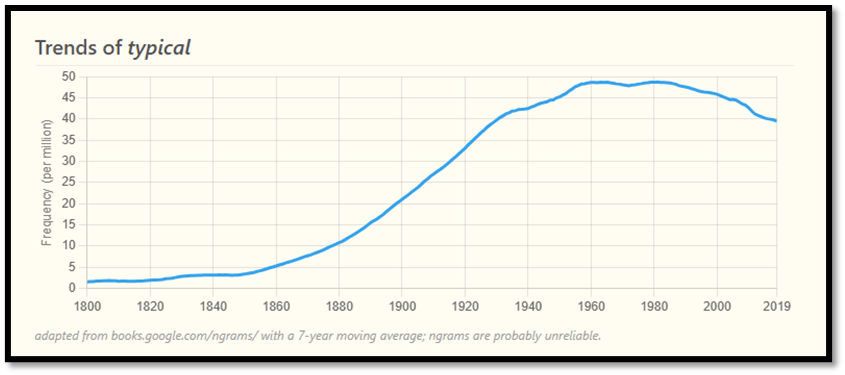

It appears that we have become obsessed by conformity to a type, as capitalism has strengthened its grip and established bourgeois order and its companion ideologies. However unreliable and invalid pointers toi firm conclusions ngrams are (and they are), in the example below the need for the word ‘typical’ has obviously become one we find it harder to do without than English speakers did in the first half of the nineteenth century, and that fits my experience of a small portion of the period pictured (1954 to the present):

This almost certainly has to do with the change of the sense of the word that etymonline.com suggests started in 1847. Once reserved for reference to the literary – even perhaps most to ‘sacred texts’ it was usual to see a ‘type’ as an aspiration. For instance Christianity scanned the Jewish Old Testament for ‘types’ of the revealed truth of the New Testament as it saw: Old Testament patriarchs were denominated ‘types of Christ’. It’s a way of thinking modern cultist versions of Christianity strive to keep alive in memes, thus:

The Christian tradition in literature finds ever newer types of Christ, Christ’s meaning or message – types embodied in rites such as baptism or in Protestant Mass once the idea of the real presence of Christ’s blood and flesh in Communion wine and wafer has been discredited by Luther and his followers. Spenser makes his Red Cross Knight a type of both Christ and England (and lots of other things in this ‘continuous allegorie and darke conceit’ in the poet’s words, his beloved Una one of the unitary divine truth in Book 1 of The Faerie Queene. All of this is important in the originative uses of the term, from the Greek before Lamarckian biology takes it over. Visual art loved to find typologies that united the holy in the life of the already sacred and the converting profane, the ritual and the everyday: even an atheist writer like George Eliot did this and the eponymous hero in her Adam Bede is a type of Christ.Irish Murdoch played the game in the twentieth century with aplomb and with no guilt about her forebears who thought truth was being made over-common – as George Eliot must have felt.

Herethen is the summary of the word’s etymology;

typical (adj.): c. 1600, “symbolic, emblematic, serving as a type,” from Medieval Latin typicalis “symbolic,” from Late Latin typicus “of or pertaining to a type,” from Greek typikos, from typos “impression” (see type (n.) in its former main meaning, “symbol, emblem, that by which something is symbolized”).

Sense development begins with use in natural history in reference to a species, “serving as the type of a genus or family” (by 1847). The general sense of “conforming to a type, characteristic in kind or quality” is attested by 1850. Use with reference to printing types is rare.

Of course, there is a relationship between older and newer dominant meanings but I doubt WordPress is thinking, in asking this question, to want people to find in their day its features that symbolise some greater, let alone sacred, truth (not consciously at least). From the nineteenth century we are more interested in ‘conformity to type’ (a kind of criteria for attesting normality and/or predictability) and that is precisely I suppose how we should answer this question. The problem is, of course, that the word has taken in our times its colour and force from the belief that there are, and moreover OUGHT to be standards that are the common meaning of our humanity – meanings that govern judgements of our ‘humanity’ within an acceptable range between extremes. This view of what is typical increasingly becomes one o an ideology – an representation in mental images and words that limits the acceptable. Against such a powerful force for conformity, people who wish deliberately to be marginal to norms would set out to rebel, and this is the very model of the artist as rebel which is promoted from the time of High Romanticism in texts, but earlier on more often in the life, of people who thought themselves great artists – notably Lord Byron, who use his aristocratic ‘apartness’ to set up a challenge to increasingly middle-class or bourgeois norms.

In France, the theme of undermining the norm itself, in literature, becomes the norm – in extremes in Rimbaud, but in popular form in Emile Zola’s novels. In visual art, those norms are continually questioned around what could be called a ‘typical day’. After all, for the eponymous heroine in Madame Bovary, a ‘typical’ day is a ‘boring day, and every nerve in her militates against boredom that cannot become the subject of romanticising imagination. Hence then the sway of the novel of adultery as Tony Tanner analysed it in Adultery and the Novel. And, if adultery become a bore why not, as in Zola’s Thérèse Raquin try murder.

Of the visual artists who pitted themselves against the ‘typical day’, as prescribed by a society ideologically run within bourgeois norms, the one I have begun to love most – and the case study for typical day antagonism in this blog – is the Swiss artist, turned French by habituation perhaps, Félix Vallotton. And his paintings are typically of adultery (and some of murder – his only [unpublished in his lifetime] novel being La Vie meurtrière (The Murderer’s Life), with his own murderous and retributive illustrations, that were to stimulate too the interest of Walter Sickert in England.

However, I am writing this now because on my last trip to London (see the blog here in proof) I bought at last an out-of-print book on Vallotton that was worth the reading: Ditta Amory & Ann Dumas [Ed.} (2019) Félix Vallotton, London, Royal Academy of Arts. This book rather overturns the myths of typicality around his life and work. For instance, it is commonplace in art history these days to lament that Vallotton’s antagonism to bourgeois ‘typical days’ was lost when he married into bourgeois wealth on 10 May 1899 to Gabriele Rodrigues – Henriques Even his most fervid psychoanalytic fan, Eugene D. Glynn, ‘husband’ (from before the title was possible) of Maurice Sendak, a Vallotton collector and great children’s storyteller – see my blog here – calls him ‘the radical disappeared into aesthetic research’.[1]

The radical he spoke of was the great friend, portrait sitter and anarchist, Félix Fénéon, the bête noire of the French bourgeois state. It is not only that Vallotton’s portraits of him painted with simplicity a man he obviously admired but also that his pictures of the anarchist arrested without reason as bourgois comfort looks on from its typical day (L’Anarchiste) show where he stood. He also showed ordinary people brutalised by the state (La Chaage) and that unrest and riot were ill understood because our sympathies are too much with the bourgeois gentleman who merely loses his top hat – ruining his ‘typical day’ (La Manifestation).

But radicals do not disappear without a trace. His Dinner by Lamplight, finished after his marriage, may predict the ‘typical evening’ in the Vallotton household but its protagonist’s presence is that of the same kind of black or darkened shadow that haunts his prints and feels threatening to a child who looks at that figure with hope, and perhaps a hint of fear:

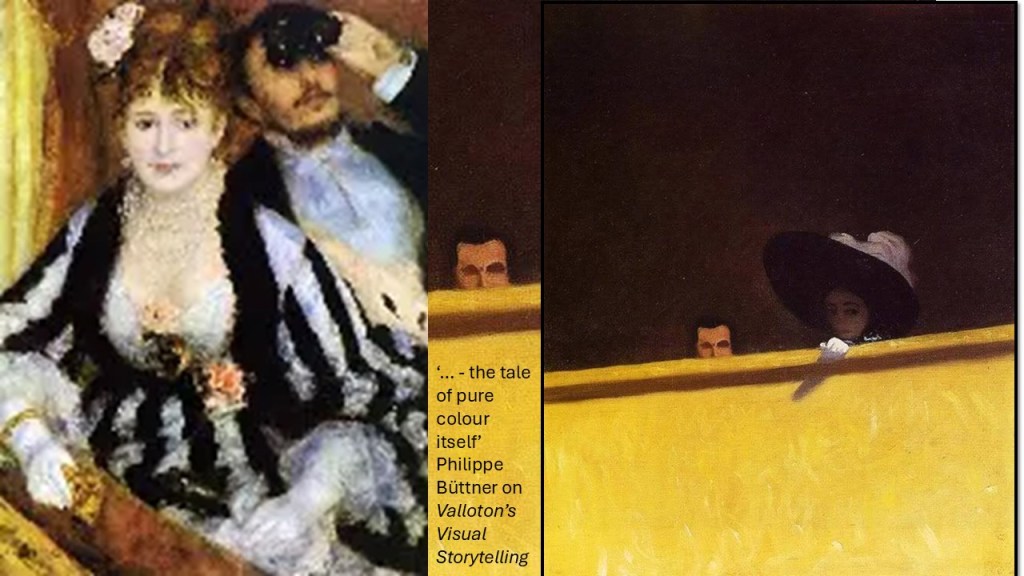

The effect of this picture’s angled knives and feral chases on its lampshade is of something entirely darkened – the type seeking its anti-type, the familiar its unfamiliar (what Freud called the uncanny), It is something Freud felt was most ‘at home’ in the familiarity of the bourgeois family’s repressed power dynamics that it calls a ‘typical day’. It might do rhat even in the glossy show of the openly adulterous relationship. Think though of how an artist might show a dashing bourgeois gentleman taking his mistress to see and be seen at the theatre. Both Auguste Renoir and Vallotton painted pictures named The Theatre Box (La Loge de théâtre), but only Vallotton produces a shocking statement of the power differential, and the vulnerability of the mistress to the young man, in his painting without passive sentimentality.

He does this by avoiding using light to entrap the deceptive appearance of the fine show made of costly appearances by this fashionable couple, betrayed only by the tearful eyes of Renoir’s gorgeous woman, aware of ‘her’ man seeking his next mistress-victim from surrounding theatre boxes. Instead the woman in Vallotton is shadowed not only under her hat but by her downward look int the floor of the ‘loge’ It all hides eyes that might betray even her vulnerability, to others (those outside the box – perhaps looking at them through opera glasses), whilst the man stares her out defiantly so that she knows his eyes are upon her but cannot return his gaze. As this silent drama occurs, Vallotton occupies his paint brush with capturing the variations of tone in the front wall of the theatre box, fronting the things it is shading within. The painting is a masterpiece, and thus, like Renoir, though it tells a story, it does so minimally such that it is, in the brilliant Philippe Büttner’s translated words, ‘the tale of pure colour itself’ we are told, wherein:

Below them the yellow front wall of the box is painted with playful brush strokes, which counter the hopeless distanced proximity of the couple with lively waves of yellow. [2]

I was first drawn to Vallotton by Eugene D. Glynn, whom I read to have insight into his husband, Maurice Sendak’s narrative illustrations. At the time I did not know Vallotton well enough but by now can even see direct rhyming echoes of their method of graphic narrative : compare the scenes below. In Vallotton’s The Red Room, Etretat a wo,man’s passion – the red here does a lot of symbolic work, threatens her baby and her family life – symbolised by the broken item that the baby examines. In Sendak’s picture Ida discovers her carelessness in loss in passionate music has led to the kidnapping of her baby sibling, whose replacement is fragile in its fragility to every element as well as human carelessness.

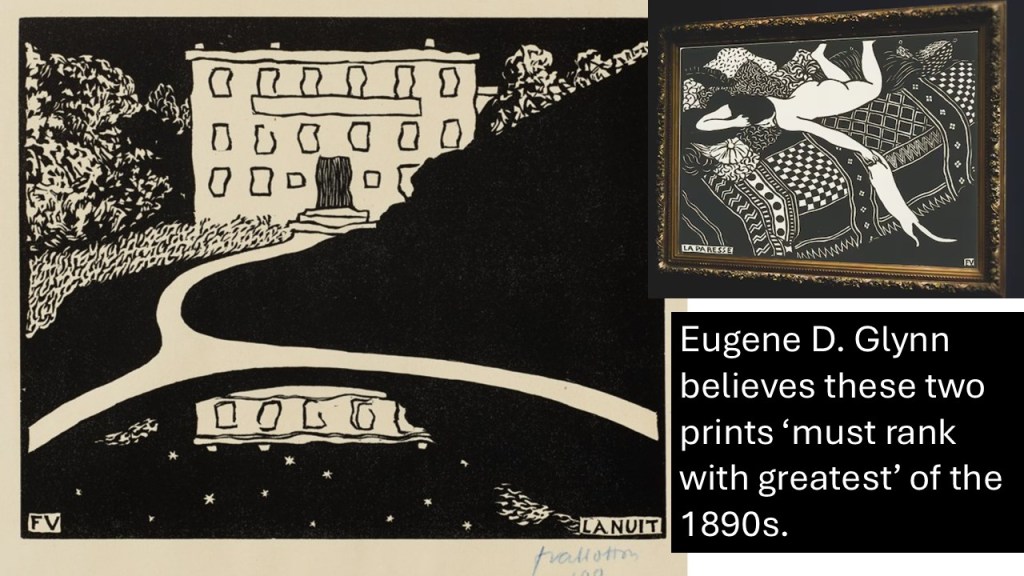

Glynn in two journal articles he wrote on Vallotton said that Vallotton’s prints (in these essays he notes his sorrow on confining himself just to the prints) that we know by the names La Paresse (Idleness) and La Nuit (The Night) ‘must rank with the greatest’ prints of the 1890s, a very fertile decade for fine wood-engraved prints.{3] The signed copy of La Nuit I picture I took from Christie’s sale catalogue online and is of Sendak’s own copy of the print, sold once both he and Glynn were dead. He is surely correct. La Nuit has the feel of a Gothic version of Van Gogh’s The Starry Night.

La Nuit is one of the most suggestive of pieces in de-typifying the appurtenances of upper bourgeois life – the grand house with a lake or pond, in which the upper floors reflect together with the otherwise unseen stars in the sky, in a relatively small garden. The house years for bourgeois stability in its typicality and regularity of form but it is defined but also deformed by pure blackness whose source is clear only in the method of woodcutting employed – these are the pieces of wood bearing no engraving of any kind. Hill and shadow can be conveyed in exactly the same way – what is clear is that Vallotton wants the home to look invaded by the things of the night:

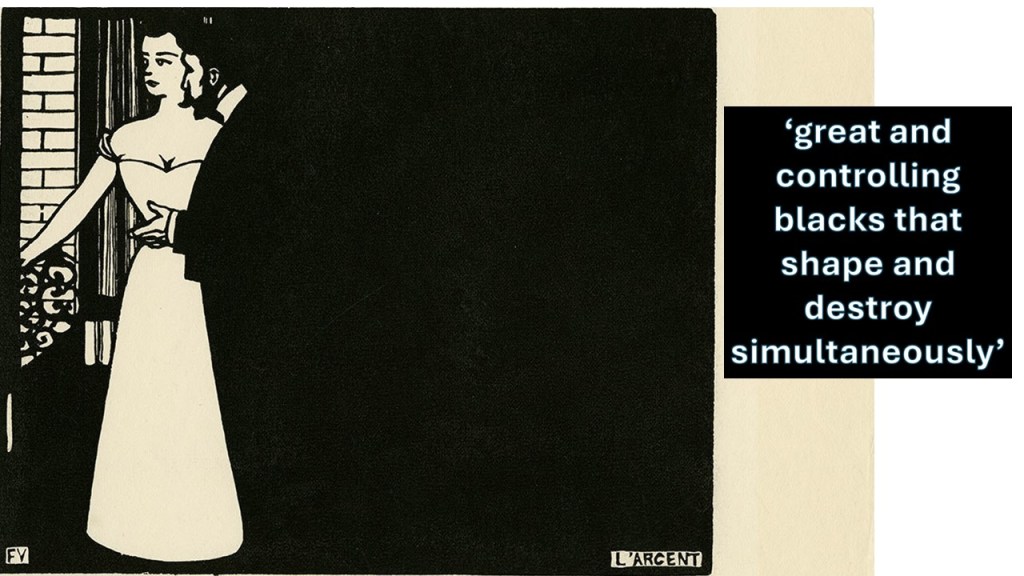

Glynn expresses it thus, but really only speaking of the Intimités (Intimacies) prints although here – but not in another example I will show you afterwards there really is no ‘line or pattern of immaculate elegance’, just formlessness occurring from different causes::

Yet everywhere line and pattern of immaculate elegance, everywhere the great and controlling blacks that shape and destroy simultaneously’.[4]

See this in its pure form in the finest of the Intimités L’Argent (Money). As always thje story is unclear. The lady seems to smile but may be glassy-eyed with a sense of the disrespect offered to her, as the beard lover shows her something – the money of the title perhaps. The vignette is elegant but the shadow blacks of the remaining print infect the lightness as is he both resists and succumbs to his aura of monied insult to human life.Being ‘shaped’ and ‘destroyed’ simultaneously must be a feeling somewhat as overwhelming as this picture.

People tend to hate Vallotton for his actual difficulty in relationships to women, but his real attack politically is always on me, whose sexuality is infected by the sources of their power: patriarchy AND capitalism, power AND money. As for male sexuality I think Glynn has him spot on. Before Intimités, Vallotton produced the series known as Instruments de Musique (Musical Instruments). Glynn describes them thus:

Men play, but for no audience or companion. Violence is gone, darkness increases print by print. silence as much as music seems to be the theme, silence and melancholy and again, sexuality. Men alone, hands and instruments highlighted in the dark – the flute player, his face a mask on the black, stares at a white cat perched directly above a statuette of a nude woman. Even the content of the masturbatory fantasy is made clear. [5]

Perhaps Büttner is wrong: even when men play – or paint playfully as the latter says Vallotton does in La Loge de théâtre – men play with themselves and purely for their own gratification, so that even their melancholy is self-indulgent, as it is is in Malvolio in Twelfth Night. Hence there is little that is light even in a supposed midsummer night scene, such as The Last of the Rays or The Pond. See the latter below, of which Amory and Dumas say that: “An ominous darkness engulfs the water that creeps menacingly across the electric-green grass’. [6]

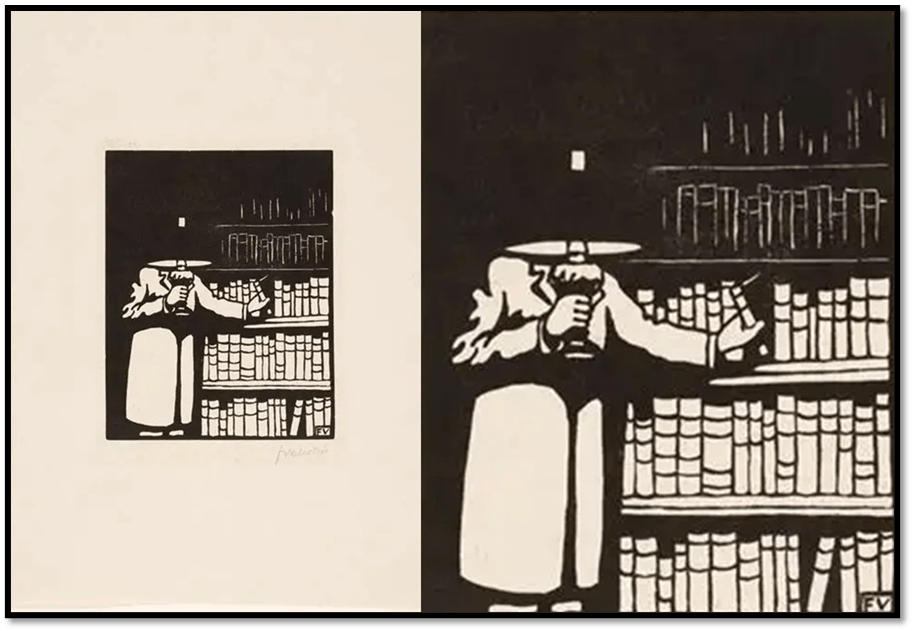

One of my favourite prints is Book Lover with Lamp in His Library (undated – see below). What cause disquiet here is that light that books might shed is all ‘owned’ by the male, who does not even share his face looking at them. What he does not light up, stays dark. Men hog the light: or at least that image of the man obsessed with the ownership of commodities – the collector. I check myself about this. I have to.

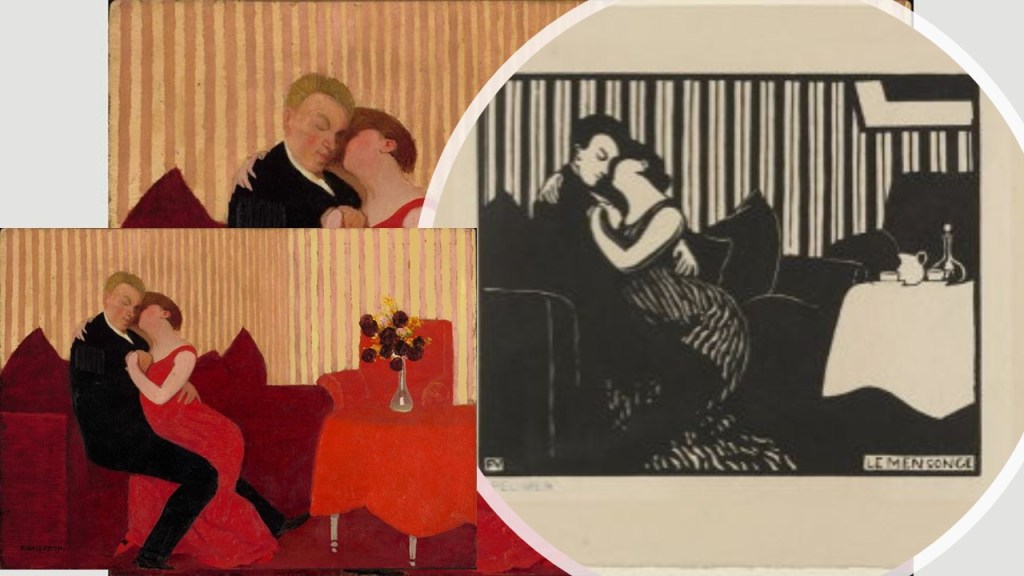

Even if Intimités are often focused on to the exclusion, as Glynn laments about himself, of the brilliant still lifes, landscapes and portraits, we should remember there was always a relationship between genres and media possible by hi. The first print of Intimités is Le Mensonge (The Lie) ut this exists as a painting as well and each has asoewhat different feel. The oil painting attempts a three dimensional room corner behind the lovers that changes ideas of depth and perspective in the painting, and the women’s striped dress is instead a red – in tonal variation with other red coverings in this almost-red room. The domestic tea things in the print are replaced by a vase of tall flowers in the painting. The hair colour of the lovers differs. Hence the lovers are not both so invaded by black colouring in the painting and are more differentiated. There is less sexual fusion in the painting too – in the print, the two flow into each other in the differentiating printer’s inks. I think this matters but I don’t know how. Sometimes you have to see the painting in the flesh to judge.

But if ‘disquiet’ is the theme of Valloton – the royal academy book before mentioned was for a 2019 exhibition named Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York as well as in London – then it is actual a painting that causes me most disquiet, as is often the case with child representations. It is possibly the nearest painting to the Nabi style of Bonnard and Vuillard that he adopted, but in mood it is more dark than either of they. The Ball (Le Ballon) shows a child chasing a red ball, although there may be a yellow ball at their rear (or is this just an illusion of light through the trees. The dark shadow of the treestoo may be in pursuit of the child and the shaping of the branches and foliage in blocks suggest claws that grasp. The only adults are in the far background but are giving no attention whatsoever to the child. This may be a ‘typical day’ in which the child is taken to a park but there is uncertainty that the usual predictions of either pleasure or peace proceeding from one of many regular trips to the park with a mother or a nanny is all that will be met there. I shudder as I look at this piece.

And even when there is humour, the darkness in the pieces make it dark humour. Because of its title, The Symphony (La Symphonie) must show a woman playing piano together with other players, Are the irascible males here other players with their instruments unseen in dark shadow in that part of the room? Alternatively, is the title symphony a metaphor which plays with the reactions of a male audience as if it were contributory to the experience of the music as a whole. Everything is dark – even the flowers in front of the window, through which there is light but not streaming within. The only light is shed by the lamp on the piano-forte offering up the outline of the woman to our – and the men in the picture’s gaze. The men are merely masks and their intent is somewhat hard to read, but not one of unadulterated pleasure or happiness. These are the men of a society whose typical day, as narrated to others, is a lie and omits their production of darkness. Hail Valloton!

So that’s me for today.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Eugene D. Glynn (ed. Jonathan Weinberg) [2008: 105] Desperate Necessity: Writings on Art and Psychoanalysis New York & Pittsburgh, Periscope publishing

[2] Philippe Büttner (2019: 39) ‘Vallotton’s Visual Storytelling in the Time of Early Modernism ‘ in Ditta Amory & Ann Dumas [Ed.} (2019) Félix Vallotton, London, Royal Academy of Arts. 35 – 40

[3] Glynn, op.cit: 111

[4] ibid: 112.

[5] ibid: 111f.

[6] Ditta Amory & Ann Dumas (2019: 17) ‘Introduction: “The Very Singular Vallotton”‘ in Ditta Amory & Ann Dumas [Ed.} op.cit: 9 – 17.